Hester Velmans’ Choice: Lucas Rijneveld and Herman Franke

Every month, a translator of Dutch into English gives literary tips by answering two questions: which translated book by a Flemish or Dutch author should everyone read? And, which book deserves an English translation? To get publishers excited, an excerpt has already been translated. Hester Velmans excites us for a ‘gripping, shocking, upsetting and gross’ novel by Lucas Rijneveld, winner of the 2020 International Booker Prize, and for the last book by Herman Franke, who died far too early.

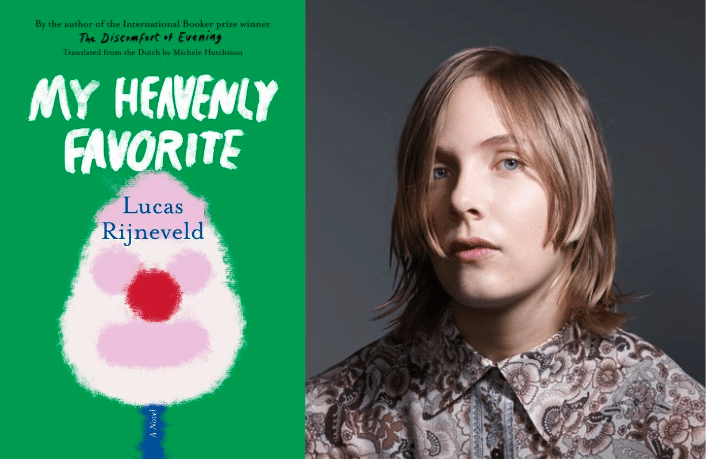

Must-read: ‘My Heavenly Favorite’ by Lucas Rijneveld

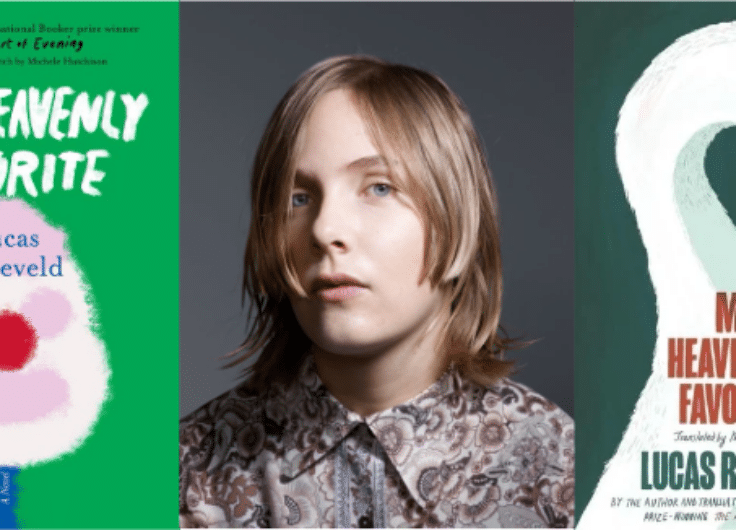

Lucas Rijneveld

Lucas Rijneveld© Jouk Oosterhof

The obsessive, destructive love affair of a 49-year-old veterinarian and a 14-year-old farmer’s daughter is told as a stream-of-consciousness confession by the vet. It’s the language that sets this book apart. The veterinary metaphors are stunningly evocative: “You lay like a breeched calf in the nursery of my degenerate desires.” The veterinary terms are almost biblical, alliterative, incantatory. The sentences run on breathlessly for pages, but they are not hard to read; they are rhythmic, persuasive, hypnotic. Set against an almost wicked delight in the descriptions of blood, excrement, puss, and insemination as the man goes about his veterinary chores, the girl’s allure (“you didn’t have bluetongue, you were healthy as an ox and incredibly beguiling”) and his own guilt (the moon is “an abscess in the sky”) are plausible and strangely seductive.

Of course, My Heavenly Favorite will be compared to Nabokov’s Lolita. Rijneveld is candid about the plagiarism: Nabokov’s phrase ‘fire of my loins’ is repeated several times. But whereas Nabokov treated the subject with world-weary coyness, Rijneveld leaps into the depravity with unbridled glee.

Into the story of the pedophile and the motherless girl, Rijneveld weaves a number of harrowing tragedies, compounding the devastation and guilt. One is the foot-and-mouth epidemic of 2001, when Dutch farmers were forced to destroy their herds. 9/11 occurred a few months later; one of the girl’s delusions is that she is the one who flew into the south tower and brought it down.

I admire this more than Rijneveld’s first novel, The Discomfort of Evening, winner of the International Booker Prize, also splendidly translated by Michele Hutchison. It is a gripping book, the imagery startling and true. It’s also shocking, upsetting and gross. Read it: you’ll be pulled into the appalling eroticism of the story through the sheer beauty of the language.

Read our review of My Heavenly Favourite HERE.

Lucas Rijneveld, My Heavenly Favorite, translated from the Dutch by Michele Hutchison, Graywolf Press, 2024, 344 pages

Lucas Rijneveld, My Heavenly Favourite, translated from the Dutch by Michele Hutchison, Faber & Faber, 2024, 320 pages

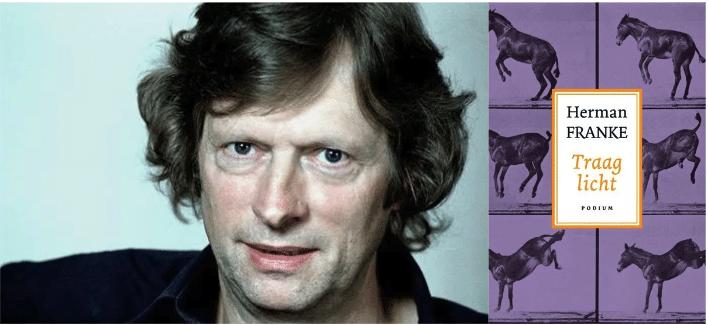

To be translated: ‘Traag licht’ by Herman Franke

Herman Franke

Herman Franke

Traag Licht (Slow Light), begun after Herman Franke (1948-2010) was told he had not long to live, takes the form of a struggle between the fictional “I” and the author himself, who is called ‘the Boss’. The narrator thinks the boss is proceeding too cautiously, since the fictional-I still has many stories he needs to get off his chest before he dies, especially his obsession with discovering the identity of the woman whose risqué early-20th-century stereoscopic portrait he once stumbled across in a flea market. The narrator is a professional writer of “portraits”, i.e. profiles, which is an ingenious way to handle a multitude of stories, leaving the reader guessing which are true and which are imagined. Some are fairy tales, some painfully realistic. Together they paint a picture of a knowing yet naïve, cynical yet innocent, romantic yet selfish, provincial yet worldly man who, in writing about others, is trying to discover the truth about himself. Franke worked on Traag licht until four days before he died.

This is one of those books that won’t let you go. I feel I owe it to the author to spread the word about it, so that his work will live on after his untimely death.

“Writers are criminals. They have the guts to recognize the evil in themselves and to acknowledge it in their stories.”

Herman Franke, Traag licht, Uitgeverij Podium, 2010, 255 pages

Excerpt from ‘Traag licht’, translated by Hester Veltmans

Incurably sick. Not much time left to live. That’s just terrible for the boss, of course, but where does it leave me? I am his creation, true. But does that mean I’ve got to let him bump me off as well? When I was just starting to get going, too; I was on a roll. I’m nowhere near finished yet, not with myself nor with all those other folks inside me. I was counting on at least ten volumes. An open-ended serial novel, he’d promised me. And, what, now I’m supposed to shut up suddenly, just like that? It isn’t going to happen. I refuse! Before the final curtain comes down, I’m determined to disgorge it all, I won’t be sent into the afterlife with a stomach full of untold stories just because he has to chuck it in, you know? I came into this world a writer of portraits, delivered from the looking-glass womb of a fictitious mother, and I’ll die in a book that ends where it all began, on the threshold of time. Either you’re an artist or you aren’t. A promise is a promise. Isn’t it?

Damn-damn-damn-damn-damn.

Actually, I didn’t think the boss was getting on with it that well anyway. He would spend days fretting over what was supposed to happen next, while I already knew; I was way ahead of him. He was afraid they wouldn’t understand me if he let me have my way, which is nonsense of course because people understand more than you think, as long as you trust them. If you don’t trust people you shouldn’t be telling them stories, because they’ll sense it and then they won’t believe you no matter what. But if you trust them, they’ll be open to listening to your stories, even to the kind of stuff they don’t really want to hear. Now he’ll just have to let go, the boss-man. He no longer has the strength to hold me back. Ha! Free at last.

So as not to waste any more time defying him, I’ll just go ahead and launch into an embarrassing story of my youth. My voice had only just begun to crack, girls were still a mystery to me, when suddenly I developed this raging desire for a microscope, the way pregnant women get cravings for herring, eel, or pickles. Cravings in pregnant women, say the scientists, are occasioned by a lack of fatty acids, but what could have accounted for my hunger, which was for a monster magnifying glass? The first explanation that comes to mind is a metaphorical one: like every right-minded teenager, I wanted to pierce the superficial surface of life in order to probe the reality which I suspected existed underneath, a reality in which dark desires were revealed, and where the solutions to existential mysteries were to be discovered.