Hilde Onis Balances Objects and Meaning

Dutch artist Hilde Onis considers her installations a kind of arithmetic sums: the addition of objects, plus the space itself, plus the viewer. She doesn’t like hierarchy, and the boundary between person and thing within her work is often blurred.

The two porcelain cups are incomplete – large parts have been removed, leaving only half of each object. It’s only then that it becomes clear that these pieces are joined together by the cup’s handle. The cups are archetypically white, but they have lost their most important function – you can no longer drink from them. As if that wasn’t enough visual confusion, both cups seem to be leaning on each other.

Hilde Onis & Liza Wolters, Orchestrating Coincidence, 2021

Hilde Onis & Liza Wolters, Orchestrating Coincidence, 2021© Liza Wolters

This small sculpture, Orchestrating Coincidence, was created by Dutch artists Liza Wolters and Hilde Onis. The sculpture was on display in late 2021, during a group exhibition in Concordia (Enschede), for which Onis was allowed to use a room for what looked like a compact solo exhibition. She seemed able to control all aspects of the space. Several of her artworks lay directly on the floor; quite small in size, no plinths, not neatly nailed to a wall. In other words, you had to watch where you were walking.

Chopped off dune

It was impossible to overlook one work in particular. Oo𝑜օₒ (2021) consisted, among other things, of a large mound of sand, containing tufts of marram grass. With the speed of a clock, these wrote O’s around their own axis, “driven” by visitors passing by. The work looked like a kind of dune pushed up against a glass wall. Outside you could see people walking along the street.

Dune, 2021

Dune, 2021© Hilde Onis

Ironically – or perhaps appropriately enough for this exhibition – Onis mostly chose work that related to delineation. She called the entire installation – so all the artworks in Concordia together – trace track thread threat, a name that mutates from a subtle trail to something oppressive. The dune, for example, looked as if it had been chopped off by the glass, and the cups were totally reliant on each other to stay in position.

Tune into the space

Onis describes herself as someone who is constantly balancing objects and meanings. Sometimes they benefit from leaning on or carrying each other, and it’s these interdependencies that are of particular interest to her. Her installations are often self-made objects – including ceramics – sometimes processed found objects, and sometimes combinations of the two. The material and the representation often seem to contradict each other.

Going to Hell in a Hand Basket, 2021

Going to Hell in a Hand Basket, 2021© Annabel Jeuring

What is also important to Onis is that a reversal or shift takes place within an image. That a piece of art initially exudes danger, and only after that tenderness – or the other way round. A good example is Going to Hell in a Hand Basket (2021), which looks like a ceramic roller coaster. Onis describes this medium as a permanent state of deceleration. The fact that the object also has a traditionally woven wicker handle leads to another shift: suddenly all that rattling excess becomes something compact that you could carry with you.

When Onis is asked to do a new exhibition, she prefers to tailor her work to the precise space she’s working in, either through creating new art, or by showing existing works of art in new ways. She sees installations and exhibitions as a kind of adding up arithmetic, in which you take something from your experience of one work of art to the next. The route the visitor walks through the space also plays a role. What can you see, and when? Being able to see the street – as was possible in Concordia – clearly influences how you experience the exhibition.

No plinths

Onis got her BA degree in sculpture at the Academy of Art & Design in Enschede. But when she started looking for an MA at the Ghent School of Art, in the same field of study, the institution turned out to view sculpture much more traditionally. For example, sculptures had to be presented on plinths – something that Onis found far too hierarchical.

Hilde Onis

Hilde Onis© Liza Wolters

Onis therefore opted to pursue the freer field of installation art – although funnily enough there they told her that her approach was quite sculptural. Here she experimented with the possibilities of performances in which objects played a role. In Soak

(2018) she puts a vacuum cleaner on a large mountain of foam, under which a humanoid figure in a costume made from scourers turns out to be lying. If you look closely, you can see the figure breathing.

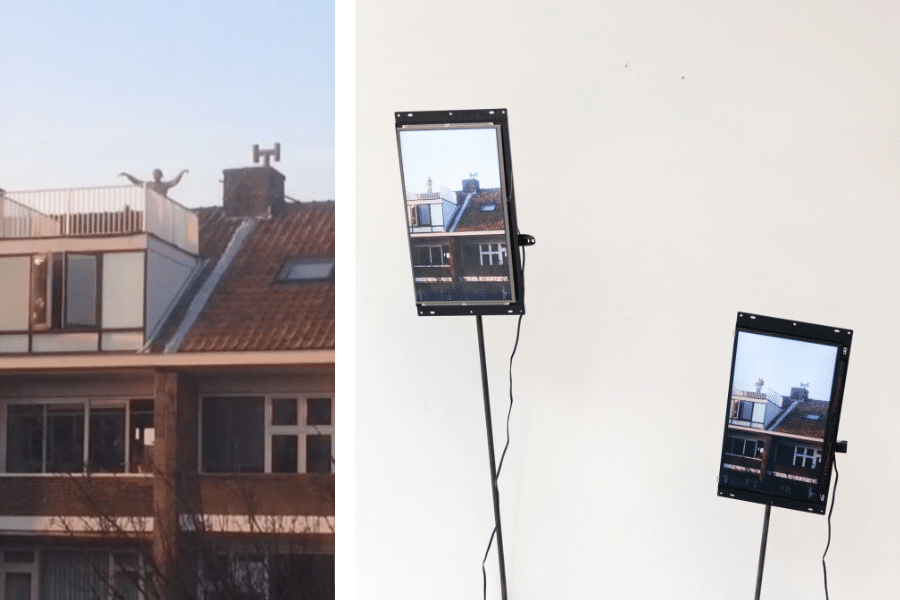

Following on from her performances, she also started to produce videos. She rarely presents these as independent work, and rather shows them within a spatial context. An example of this is Flying Neighbor (2018), in which a man on a roof is making ominous arm movements. Will he really do it? This impression shifts when he then lifts a baby up. Onis considers the scene a lucky find that she gratefully uses. The graininess of her phone camera also gives the scene something fleeting and sketchy.

Video above eye-level

Appropriately, she sets the small screens displaying Flying Neighbor to protrude from the wall, at just above eye level. This corresponds to how she had to direct her gaze upwards in order to register the filmed image. In this way the installation indirectly evokes a physical experience too.

Flying Neighbour, video and installation, 2018

Flying Neighbour, video and installation, 2018© Hilde Onis

In any case, spatial art quickly brings to mind your own body, because of the dimensions and freer positioning. Your own position then becomes part of a temporary cohesion, of which you can sometimes become very aware – especially when the sculptures aren’t positioned on plinths, and instead they’re on the floor.

Incidentally, Onis has not yet finished her studies: in 2022 she started a course at the Schrijversvakschool (Writers School) in Amsterdam. Her art often also has a linguistic component. You can see this reflected in her approach to title boards, as she often chooses not to position them directly next to the artwork. Instead, she prefers to merge the titles into a text that can be read as a poem that hangs somewhere in the space. This list looks totally different for each exhibition of course – cohesion is often only temporary.

Noble and greedy cups

The aforementioned cups are part of a whole series that Wolters and Onis are exhibiting from mid-January, titled Orchestrating Coincidence. They came up with the idea when they came across a photo on the internet forum Reddit, of a cup that happened to be broken in such a way that only the handle held the halves together. In the middle of the covid pandemic, it became a popular photo, to which forum visitors attached all kinds of personal associations.

Wolters and Onis deliberately wanted to recreate that coincidence by carefully processing a copy of the cup from a charity shop, using a grinder. In the end it became a whole series of works, each cup with its own “fault lines”.

As the series grew, the artists began to think about the nature of collecting. A catalogue was a logical next step. The catalogue contains all of the objects, including two duos, that have been assigned character traits based on their shape – noble, benevolent, or greedy, for example. When you fully unfold this leporello, it is about two meters wide, which is about the average person’s reach. There’s often a person hiding indirectly in Onis’ objects.

Thing, person, energy

A recurring theme in Onis’ oeuvre is the blurry dividing line between man and tools. Everyday life is full of objects that serve as extensions of us, from clothes with which you can express your identity to the smartphone that allows you to communicate with others from a distance.

Why shouldn’t this blurring work the other way, for example by giving objects their own energy or personality? Onis notes that her materials also have their own will, which you can go against or go along with, and in this way, unexpected connections can be discovered.

Orchestrating Coincidence is on view until 25 February at art space Nieuw Charlois (Rotterdam). Also on view during the Boring Festival, 20 and 21 January, is an installation of stained glass objects in the Janskerk (Haarlem). More info via the website of Hilde Onis.