On a visit to the Flemish city of Halle, Derek Blyth discovers a miraculous statue, a forgotten Flemish artist and an intriguing street art trail.

© vzw den AST

It’s not the same, I realised when I stepped off the train in Halle. The old Flemish Renaissance station had gone, replaced by a contemporary building in the middle of a vast concrete square. What happened to the old station? I wondered.

The answer comes soon enough, as a high-speed train rushes unseen through a tunnel, heading in the direction of Paris or London. The passengers unaware that their smooth journey comes at the cost of a handsome Flemish Renaissance building.

The old station with its nostalgic wood-panelled bar was designed in 1887 to welcome the many thousands of pilgrims who travelled to Halle. They came to pray in the great Gothic Basilica of St Martin in the heart of the city where a miraculous black statue of the Virgin was placed in the 13th century.

But the station was torn down in 1995, leaving nothing except a stone carved ‘Halle’ inside the ticket office. There were plans at the time to reconstruct the historic building in a different location. But I somehow think that is not going to happen. It would take a miracle.

I set off in the footsteps of the pilgrims. They were drawn to Halle by a statue gifted to the town in 1267 by Mechtildis of Brabant. According to the local legend, the Virgin saved the town from disaster when Philip of Cleves stormed Halle in 1489. His guns bombarded the city with 470 stone and iron cannonballs. But the Virgin managed to catch the cannonballs one by one in her robe. Clever.

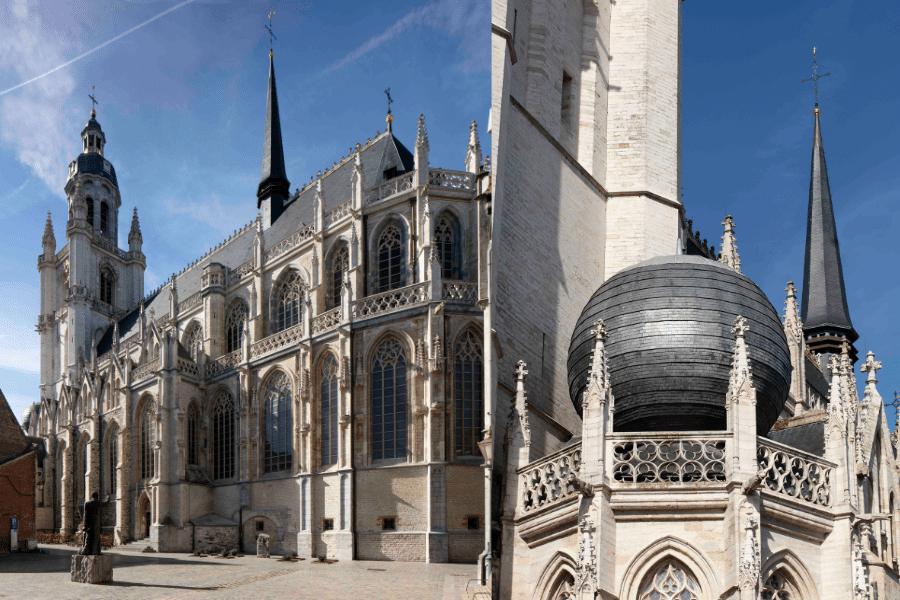

The Gothic Basilica of St Martin and its curious sphere, symbolising the world created by God.

The Gothic Basilica of St Martin and its curious sphere, symbolising the world created by God.© Stefan Dewickere

The statue is now displayed in a beautiful Gothic basilica decorated with gargoyles, carved figures and beautiful oak doors. The strangest detail is a curious sphere perched on top of a tower. It was constructed by skilled craftsmen in 1440 without using a single nail. Perched above the baptismal chapel, the sphere represents the world created by God.

As I entered the basilica, I noticed a stack of cannonballs in a stone alcove closed off with a heavy iron grille. All carefully gathered by the Virgin in her robe. I read in a guide that anyone who correctly guesses the number of cannonballs will enjoy a happy and fruitful marriage. All right, it can’t be that difficult. I count 32. Or are there 33? No, definitely 32.

According to the local legend, the Black Virgin saved the town from disaster when Philip of Cleves stormed Halle in 1489.

According to the local legend, the Black Virgin saved the town from disaster when Philip of Cleves stormed Halle in 1489.© Anne Callens

The Black Virgin that saved Halle from destruction is on display high above the main altar. A copy sits in a side chapel lit by hundreds of little red candles. Posted on the chapel walls, stern notices list the price of the candles. The smallest cost 50 cents. Larger ones, 2 euros. The big candles, 4 euros. Hier betalen, pay here, it says above a wooden box.

The Church claims the Virgin was blackened by gunpowder as she stopped the cannonballs. But a different explanation, possibly more plausible, is that the figure was slowly blackened by smoke from all the burning candles.

The walls of the basilica are hung with dark oil paintings illustrating miraculous events attributed to the Virgin. Some of the paintings are so high and so black that it is hard to make out anything. ‘She saves 13 men in a shipwreck in 1405,’ it says on one painting. ‘She miraculously delivers an innocent man from the gallows,’ another says. In a more recent miracle, in 1826, she saved the Countess of Villegras from drowning when her carriage toppled into a canal.

A slow tour of the basilica reveals some quirky wood carvings in the side chapels. One cheeky local artisan carved two giant ass’s ears on a bishop who refused to grant indulgences. Another tiny carving in the style of Bruegel shows a Flemish mother with her baby wrapped up like a parcel.

Interior of the Basilica of St Martin

Interior of the Basilica of St Martin© Stefan Dewickere

The carvings sometimes take a morbid turn, like the six sculptures representing a dance of death in which three men on horseback are startled out of their wits by three grisly corpses. ‘You will soon be like us, we were once like you,’ the viewer is warned.

The saddest memorial is a tiny black marble figure in a Gothic niche. It was carved in memory of Joachim, a son of Louis XI of France, who died in Halle in 1459. The figure of the little boy no larger than a doll.

Memorial of Joachim, a son of Louis XI of France, who died in Halle in 1459.

Memorial of Joachim, a son of Louis XI of France, who died in Halle in 1459.© Stefan Dewickere

As I stepped out of the basilica, I realised something had changed. The last time I visited, years ago, there were several shops selling religious souvenirs clustered around the basilica. But they have all gone, every last one, leaving just an empty shop with the words Articles Religieux above the door, and another with a beautiful Art Nouveau façade, the interior stripped bare of every saint and crucifix.

The annual pilgrimage to celebrate Pentecost was once a huge event that brought more than 150,000 people to Halle. There were special trains laid on to bring the faithful. But Halle has become less important as a pilgrimage destination. The Jesuit College behind the church where pilgrims were once welcomed is now the local art academy.

There are still many devout Catholics who come to Halle, some of whom walk the historic five-kilometre pilgrimage route through Halle.

There are still many devout Catholics who come to Halle, some of whom walk the historic five-kilometre pilgrimage route through Halle.© vzw Den AST

Yet there are still many devout Catholics who come to Halle, especially in May, when the city welcomes several thousand pilgrims, some of whom have walked more than 100 kilometres. It ensures that Halle’s historic five-kilometre pilgrimage route

has survived. Marked with a little hexagonal sign, De Weg-Om follows the lanes and alleys that the faithful walk along in an annual procession. I set off along the route, the only pilgrim on a cold January morning. It led through the streets of Halle and out into the fields. Along the way, there were little white chapels with statues of the Virgin in niches, each one different.

Back in Halle, I went in search of coffee. The area around the basilica had several appealing spots. The bike and coffee bar Falco looked good. The bookshop BOEK had a little coffee corner with comfy armchairs. But I finally dived into Mokkadis, a coffee shop where they roast their own arabica beans. It’s a relaxed, friendly place decorated with oak beams, stone floors and stained glass.

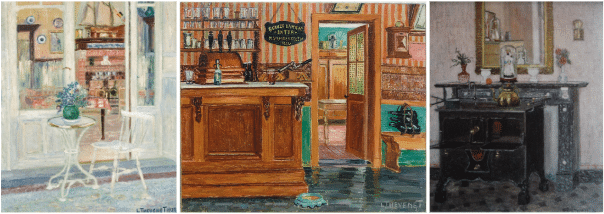

I had picked up a pile of leaflets in the tourist office. They were full of inspiring ideas for walks and bike trips. Enough to fill a couple of days. First stop, the house of the artist Louis Thevenet. Born in Bruges in 1874, Thevenet settled in Halle in 1916. He mainly painted domestic interiors in the warm colours of the Fauvists. Not great art, not Van Gogh. But warm, comforting.

Louis Thevenet mainly painted domestic interiors in the warm colours of the Fauvists.

Louis Thevenet mainly painted domestic interiors in the warm colours of the Fauvists.© Freddy Busselot / vzw Den AST / Freddy Busselot

He filled his paintings with everyday objects, like a summer hat, a cupboard with an open drawer, a piano, an umbrella. Sometimes he added a person in the room. A small girl sitting on a step, a woman in front of a mirror. Scenes of domestic contentment.

Thevenet lived in a lane near the basilica called Sollembeemd (the house was torn down in about 1970). He then moved into a house at Hendrik Consciencestraat 58. A bronze plaque on the wall (a bit too high to notice) marks the house where he lived until his death in 1930. His paintings are now scattered around Belgium in museums and private collections. Mostly forgotten.

But that might change in 2024. The city plans to organise an exhibition to mark 150 years since the birth of the painter Louis Thevenet. But first they have to track down the paintings hidden away in private collections.

View of the house of Thevenet, who lived in a lane near the basilica called Sollembeemd. The house was torn down in about 1970.

View of the house of Thevenet, who lived in a lane near the basilica called Sollembeemd. The house was torn down in about 1970.© vzw Den AST

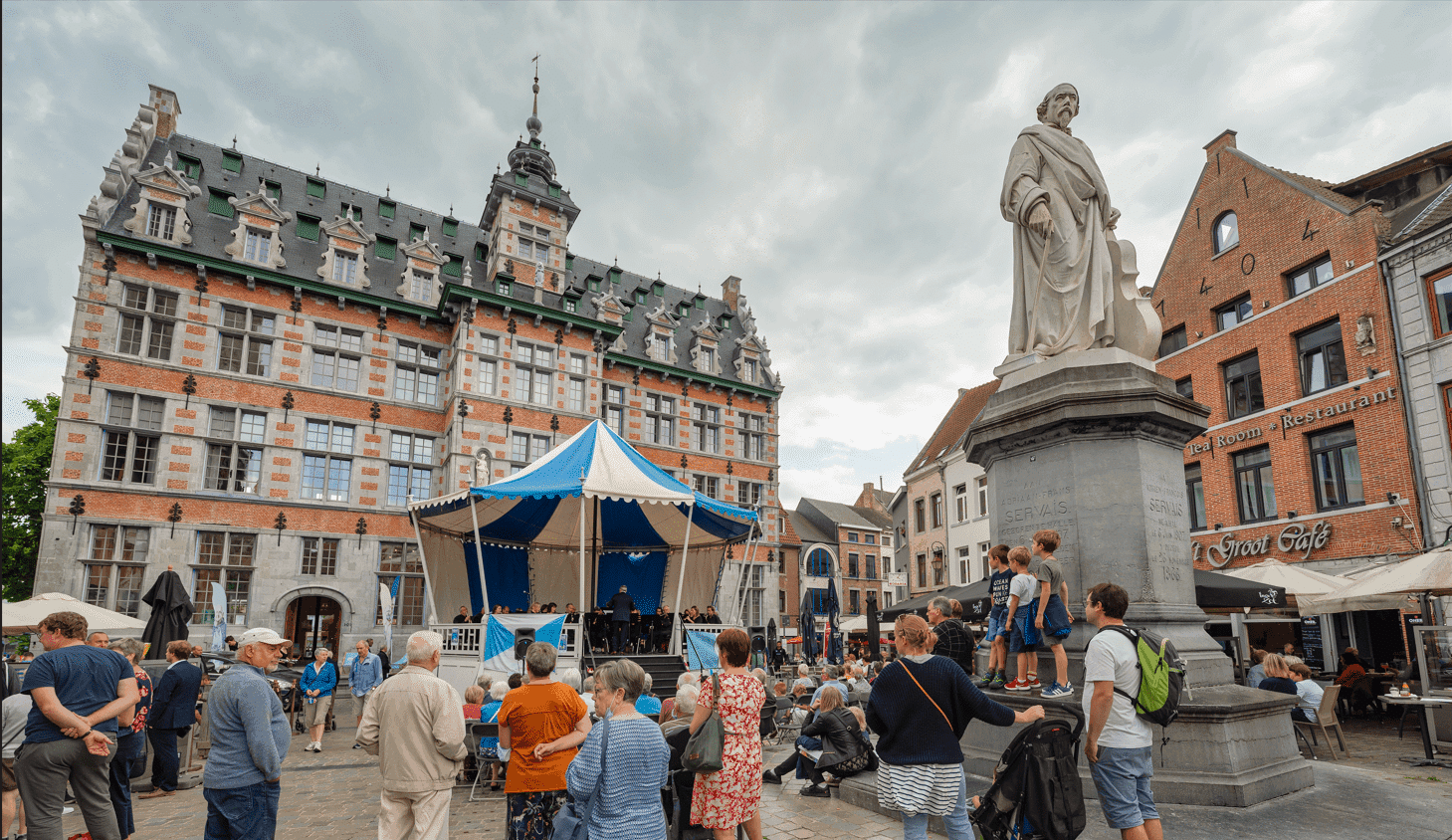

Next stop, the Villa Servais, which stands on a low hill above the old town. A neoclassical villa with pale yellow walls and symbolic reliefs, it looks as if it belongs in Italy. It was built in 1847 by Jean-Pierre Cluysenaar (architect of the Galeries Saint-Hubert in Brussels) for the cellist and composer François Servais, who is commemorated by a 19th-century statue on the Grote Markt. Servais travelled around Europe as one of the most famous cello virtuosos of the moment. At his Villa in Halle, he came to rest and received his many artistic friends and students. There he made music in his own concert hall.

The villa was abandoned in the 1980s. It might have been lost forever. But two local art lovers, Maud Leschevin and Geert De Poorter, came up with a bold plan in 2016. They bought the crumbling villa and lovingly slowly restored it over five years. The villa opened in 2022 as a unique B&B and concert venue. It has eight guest rooms decorated in period style, along with an elegant tearoom and a concert room.

The former house of cellist and composer François Servais is now a unique B&B and concert venue.

The former house of cellist and composer François Servais is now a unique B&B and concert venue.© Villa Servais - photo by Emile Devogeleer

It is a sublime place to stay, every detail carefully considered. The period furniture. The bed linen. The perfumes. Even the teacups are handmade by the Belgian ceramist Kim Verbeek. I wasn’t able to stay here, but hope to go back one day, just to spend a night in this unique setting.

From here, I headed back to the basilica. Once across the canal, I turned into the Albertpark. This modest city park offers an informative lesson in Belgian history. Over there, a memorial to King Albert I stands on a fake rocky peak, symbolising the mountain where he fell to his death in 1934. And who is that in the corner? It is a bronze bust of King Leopold II placed here in 1953 when the king’s reputation was still basically intact (at least in Belgium) for bringing prosperity and civilisation to the Congo.

In the Albertpark, a memorial to King Albert I stands on a fake rocky peak, symbolising the mountain where he fell to his death in 1934.

In the Albertpark, a memorial to King Albert I stands on a fake rocky peak, symbolising the mountain where he fell to his death in 1934.© vzw den Ast

The group Decolonise Halle has created a 2.5 km walking trail through the city Langs koloniale sporen (Past traces of colonialism). The free booklet (available at the tourist office) guides you to spots with a link to Belgian colonial history, including street names that honour people from Halle who played a role in the Congo.

So much for the past. Halle now feels like a tolerant place with some interesting street art, including woodland animals painted on electricity cabins. But there was one work I really wanted to see. It was created inside the Paterskerk, a rather grim Neogothic brick church built in 1902. I tried the door. It was locked. The church is currently being restored, but you can track down images online that reveal the magical jungle landscapes painted on the church walls.

Street art by Bart 'Smates' Smeets en Steve Locatelli inside the Paterskerk.

Street art by Bart 'Smates' Smeets en Steve Locatelli inside the Paterskerk.© Kevin Faingnaert

There are several other works of street art to discover in Halle and the surrounding villages. The tourist office has created a 21-kilometre bike tour taking in nine works, including a giant rabbit painted by Gijs Vanhee on a brick tower, and a long wall of art by international street artists at the railway station.

Street artist Gijs Vanhee painted a rabbit on a brick tower.

Street artist Gijs Vanhee painted a rabbit on a brick tower.The most impressive work is just outside Halle, next to the canal that runs to Charleroi, where the street art collective Treepack has created a long mural on a factory wall. The work, called Het Betoverde Bos, The Enchanted Forest, is one of the biggest street art projects in Europe. It illustrates a contemporary fable involving a girl from Halle who creates a small bird from rubbish left along the canal. A boy joins her, and various animals settle along the canal as the polluted water is cleaned up.

Part of The Enchanted Forest, a gigantic mural next to the canal that runs to Charleroi.

Part of The Enchanted Forest, a gigantic mural next to the canal that runs to Charleroi.© Kevin Faingnaert

The Enchanted Forest is part of a project by Halle to improve the landscape of the Zenne valley. The meandering Zenne was once lined with 19th-century factories decorated with mediaeval battlements and towers where the owner could look out for barges arriving by river. Most of the factories have gone, leaving a waterway that serves only as a convenient dumping ground for all sorts of waste.

The city has launched a progressive ecological plan to turn the Zenne valley into a green riverside park.

The city has launched a progressive ecological plan to turn the Zenne valley into a green riverside park.© stad Halle

But that will change, the city says. It has launched a progressive ecological plan called Zinderendezenne – Scintillating Zenne, you might say – to turn the valley into a green riverside park. The plan is already beginning to take shape in Halle, where several viewing platforms have been built along the river as it meanders through the city.

***

A forest outside Halle has become famous in recent years. You might almost call it a new pilgrimage spot. One that has knocked the Black Madonna off her throne.

The woods known as the Hallerbos to the east of Halle are filled with blue flowers that flourish every spring on the wooded slopes. Up until recently, the ‘bluebell woods’ were only known to locals. But then people began to post photos of the magical ‘Blue Forest’ on Instagram and TikTok. And the Hallerbos suddenly became somewhere you must see before you die.

Halle now brands itself as Hyacintenstad, the Hyacinth City (the flowers that grow there are actually wild hyacinths, not bluebells). It organises a Hyacinth Festival every year in that brief period when the flowers appear – once the soil is warm enough, but before the trees block out the light, usually from mid-April to early May. The city’s rubbish bins are even decorated with photographs of the woods.

The blue hyacinths of the Hallerbos attract thousands of visitors from all over the world.

The blue hyacinths of the Hallerbos attract thousands of visitors from all over the world.© De Stercke

But there is a problem. The narrow country lanes leading to the woods become blocked with cars as thousands of people set off to secure the perfect Instagram shot. Some people like to pose in the middle of a sea of blue, which can easily kill off the delicate flowers. In an attempt to manage the crowds, the city has marked out a bike route starting at the station. It also runs free shuttle buses at weekends. But too many people still choose to go by car.

I decided last year to rent a bike at the station. It looked like an easy ride that followed the Flemish numbered sign system (knooppunten, in Dutch). The route started at No. 65, then on to 53, followed by 50. But I hadn’t anticipated a series of steep hills along the way. An electric bike would have helped. But anyway. I finally made it to the woods.

The bluebells don’t appear immediately. They grow deep in the woods, on slopes warmed by the sun. I turned down a quiet trail, that I saw the extraordinary blue haze that spread across the entire woodland like an Impressionist painting. It is, I have to agree, something you have to see before you die. But ideally on a quiet day.

Serious beer fans can plan a tour of local Lambic breweries in Halle.

Serious beer fans can plan a tour of local Lambic breweries in Halle.© Brouwerij Boon

Then it was back down into Halle on quiet lanes. And one last thing to do before I left. Another pilgrimage, sort of. Beer fans come to this region to visit the famous Lambic breweries in the villages of the Pajottenland. They often try to drink a beer in the local cafe regularly voted the best bar in the world, some 15 kilometres from Halle. The café is called ‘In de Verzekering Tegen de Grote Dorst’ (At the Insurance Against a Great Thirst), open on Sundays and holidays, and sometimes after a funeral.

Serious beer fans can plan a tour of local Lambic breweries taking in Brouwerij Boon in Halle (which has a visitor centre) and the microbrewery Den Herberg in Buizingen. They can also visit the local history museum Den AST, which occupies a former malt house, to learn about the malting process

Aerial view of Halle's main square

Aerial view of Halle's main square© vzw Den AST

The Lambic tour might end up on Halle’s main square, the Grote Markt, in one of traditional cafes. Maybe Café Den Obelix, where an old beer sign on the outside wall advertises Gueuze Boon, brewed in a traditional farm brewery. The menu lists more than 80 beers, including a number of local and elusive Gueuze beers. I suggest you try Gueuze Boon, although you might not like it, if you have never had a Gueuze. It has a strange sour taste. But take another sip. Eventually it might hit you. This is seriously good beer.

Enjoying a beer at microbrewery Den Herberg

Enjoying a beer at microbrewery Den Herberg© Kevin Faingnaert

Before I left Halle, I took a last look at the beautiful basilica. Several new shops and cafés have opened up around the church. A bike dealer. A concept store. A cool coffee shop. The city is encouraging young people with fresh ideas to start their own businesses. They are bringing new life to this historic quarter

But what about the abandoned shops that once sold statues of the Virgin to devout pilgrims? Surely, they should be occupied, I thought. A plaque was attached to the wall of one empty building. It recalled that it was once an inn called Den Hert, The Deer. And there was more to tell. For it was here that Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, died on 27 April 1404.

The duke had fallen sick in Brussels. He wanted to get back to his wife Margaretha van Male in Atrecht as quickly as possible. But his illness got worse along the route and he stopped in Halle to pray to the Black Virgin. It didn’t save him. The duke died in Den Hert.

Then I spotted a tiny sign in the shop entrance next to Den Hert. Halleluia, it said. Nothing more. I had to search online for an explanation. It seems the local parish recently bought up Den Hert and the building next door. The plan is to create a contemporary centre for pilgrims, opening in 2025. People can meet up, or even spend the night here. The name is perfect. It will be called Halleluia.

Rejoice! I thought. The pilgrims are coming back to Halle.

This article was realised with the support of the Flemish Government.