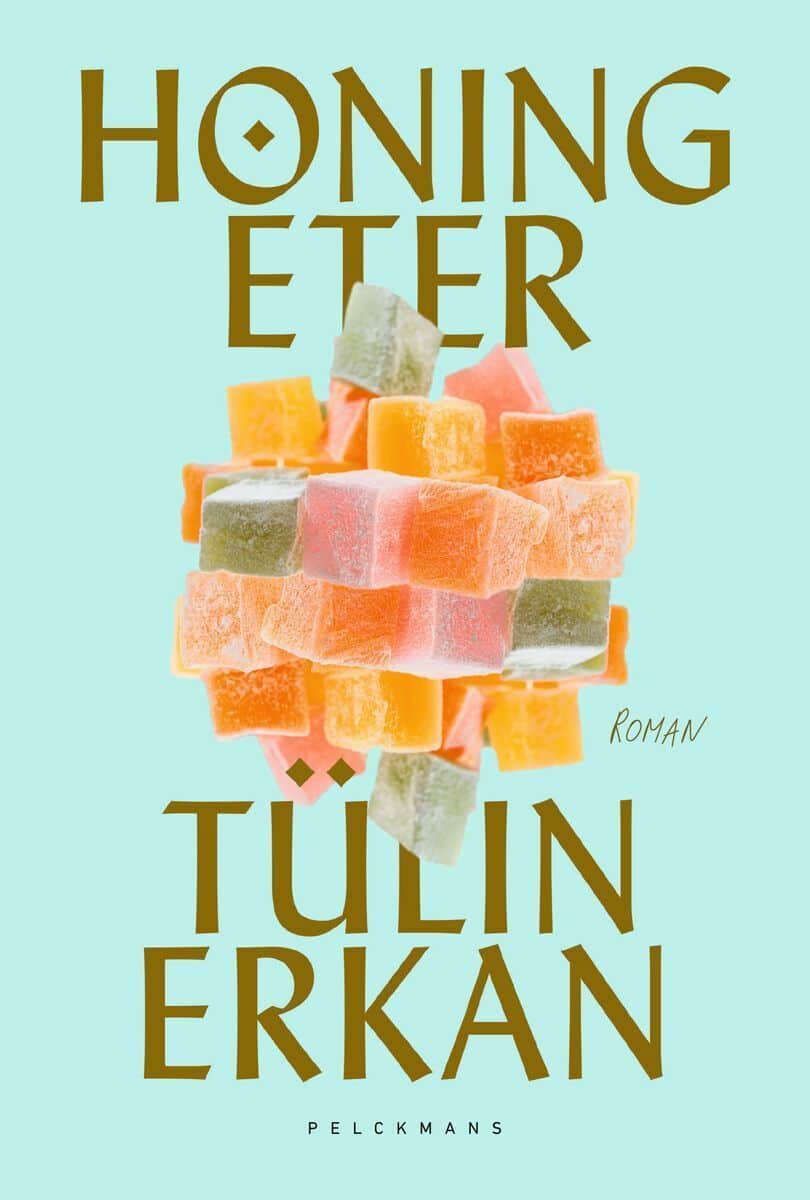

‘Honingeter’ by Tülin Erkan: An Exercise in Saying Goodbye

With Honingeter (Honeyeater), Tülin Erkan has written a debut novel about searching for the right words and about how difficult it is to say goodbye to places and people, even when you never really fully feel at home.

The setting of a novel can sometimes be as crucial as its characters or its plot. The first detail we often remember about a book is where it takes place. In the case of Honingeter by the Flemish debut author Tülin Erkan (b. 1988), it is a defining feature. We are in Istanbul airport, and except in the dreams and memories of the characters that is where we stay for the whole story.

Tülin Erkan

Tülin Erkan© Bloovi

That airport is a “place where people melt like candle wax”, Erkan writes in her opening lines, and where they “solidify instantly when a voice over the intercom calls out their flight number or announces yet another delay”. The tone is immediately set. According to Erkan, an airport is also a place where getting lost has become an art, because everyone has to take the same route.

Honingeter (Honeyeater) is the story of Sibel, Ömer and Wernicke, three characters well versed in the art of getting lost, perhaps they are even trying to disappear. They are running away, yet they do so by lingering in the same place. Because at the same time they seem to be looking for something, although we don’t always know what.

Ömer is a security guard who watches surveillance videos all day and never goes home. Sibel is a woman who misses her flight to Brussels every day. Ömer begins to watch her movements on the screen, but also in real life. She feels this. Or does she notice the red lights blinking in the cameras?

Erkan tells the story of Ömer and Sibel in separate chapters, each time from their perspective. It sometimes takes a while before you identify the narrator, which is entirely fitting for a book about soul-searching. As reader, you sense that the two will edge closer together, although it eventually happens in an unpredictable way.

While Ömer and Sibel are busy following and leaving each other in peace, Wernicke turns up. He is a pilot who is no longer permitted to fly, although he tries carefully to hide it from Sibel. She plays along. It is unclear what exactly is wrong with Wernicke, although he increasingly has to search for words, which indicates a brain malfunction. His name isn’t Wernicke by chance, of course.

A bond of sorts develops between the three characters, without it being expressed or put into words. An airport dog nearing retirement provides the connection. No one asks difficult questions, they all tolerate one another’s laborious searching, a search for words, for somewhere to feel at home.

Erkan intersperses her story with memories, whereby we slowly learn a little about why these people take refuge at the airport. Ömer thinks of his Turkish native village, but also of the mines in Winterslag and the wife and children he left behind. Sibel thinks of her interrupted veterinary studies, of her father who disappeared from her life at a young age, and of the holidays with her Turkish grandparents. And Wernicke thinks of the cities to which he once flew.

In this way, we get to know all three a little better, although Erkan leaves more than enough room to flesh out all those stories, all those characters. She writes cinematically, in scenes, without giving a lot away. Much is left to the imagination of the reader, who can happily daydream between chapters.

A few lines from ‘Ne me quitte pas’ by Jacques Brel at the start clearly introduce the subject of the novel. This is a book about (the difficulty of) saying goodbye, about finding a place where you can be at home, in language or physically. Together we are displaced, Sibel sighs to the airport dog she spends her days with, and in whose kennel she sleeps at night, listening to his heartbeat.

It is also a book about seeing and being seen, about trying to forget, but also about forgetting words, and being forgotten, as a daughter, as a father.

Over time, the three characters each start to hope they will stay together, but they know that is not possible, that the end is not far off. A snowstorm extends their awkward togetherness for a while, but in the end, parting is inevitable.

An excerpt from 'Honingeter', as translated by Paul Vincent

Terminal 226

I wonder whether escalators forget footsteps. To what point they guess the shoe size, the weight, the destination of those who travel up and down on them. And whether they retain the information, for another time. I have sat here for quite a while, 572 passers-by to be precise. I keep a tally of the number of passers-by in my notebook, so I can make a note of everything that passes by. For as long as I have to, I keep track of what passes by. I want to turn to stone here and swallow back departure, finally and for good. I turn my head to the left and look straight through passengers, neon lights and distorted mirror images at the crescent-shaped moon, which in a while, when the sky darkens like blotting paper, will light the snow-covered peaks in the distance. Once active volcanoes, today smouldering peacefully, until another tectonic plate shifts. Meanwhile Istanbul bubbles up like magma.

Things go slowly in an airport, perhaps because everything repeats itself endlessly in loops: the people who are on the move, the luggage belts, this escalator. And constantly start anew. 572 passengers ago I sat down at right angles to this escalator because its cadence reassures me. The mechanism swallows up the steps and swells again with a dull click. I wish I could do that too, swell again.

It began a long time ago: I lost my words. Or rather, I simply swallowed them again. Something in me refused to pronounce them. They welled up in my belly and came just as far as my Adam’s apple. There they got caught and lodged in my soft palate, until I could produce nothing but air. Sometimes so many words tried to bubble up that they formed a tough lump, testing my throat cavity to the limit. Like when you try to swallow too large a mouthful of stale bread. Then I wished I could vomit up the sickening mess of words, and could be simply relieved of it. When I was still studying, it wasn’t so obvious. I hid in scientific Latin terms and veterinary taxonomy, a different sort of language, with which I could convince lecturers, mainly in writing. Only when I was alone with animals in the lab could I speak fluently and freely. Squeaking with the mice, croaking with the frogs, growling with the dogs.

Nowadays I am occasionally able to get a word to the tip of my tongue in the presence of people. It tickles so badly that the word comes out impatiently too early, jerkily. I read somewhere that it is not possible to swallow your tongue. That reassures me.

Tülin Erkan, Honingeter, Pelckmans, Kalmthout, 2020, 208 pages