On a trip to Vilvoorde, near Brussels, Derek Blyth discovers a monument to an English martyr, a traditional horsemeat restaurant and a waterfront that looks like Brooklyn.

I had taken the train to Vilvoorde that morning. It’s just ten minutes from Brussels on the oldest railway line in continental Europe. ‘Don’t be put off by Vilvoorde station,’ a friend told me, when I announced the plan.

He wasn’t kidding. The station was built in 1882 in a grand Flemish Renaissance style. But it now needs some serious attention. The elegant ironwork is rusting away. The six platforms are desolate. And the damp underpass is not somewhere you would want to walk through at night.

The local mayor Hans Bonte threatened to shut down the station because he was afraid it might collapse. The building is now being renovated, but slowly. The work won’t be finished until 2024, according to the most recent estimate. ‘A station sends an important message,’ a local politician complained. ‘If an international traveller steps out into a dirty and ugly station, they are going to wonder what the rest will be like.’

So let us see what the rest is like, I thought. And, to be honest, it didn’t look great. A busy traffic roundabout. A couple of bars, both closed. An illegible city map. And no hint of any tourist office.

Across Vilvoorde station, you can relax in the romantic Hanssenspark, named after Edmond Hanssens, mayor of Vilvoorde at the end of the nineteenth century.

Across Vilvoorde station, you can relax in the romantic Hanssenspark, named after Edmond Hanssens, mayor of Vilvoorde at the end of the nineteenth century.© City of Vilvoorde

But it immediately becomes more interesting on the other side of the road. A gate leads into a romantic park with an iron bridge, a restaurant in a modernist pavilion and a crowd of angry geese. The city centre is soon reached down a handsome street lined with solid 19th-century houses. Some with art nouveau details or a romantic garden, relics of the period when Vilvoorde’s wealthy families lived near the station.

I was heading towards the Gothic church spire. Always a good plan. But Vilvoorde’s Church Of Our Beloved Lady is stranded in the middle of another busy roundabout, next to a big Lidl supermarket. The church was unfortunately closed that morning.

The neoclassical town hall

The neoclassical town hall© City of Vilvoorde

Now I was looking for Grote Markt. The main square where you are likely to find the cafes and restaurants. The square was behind Lidl. It had a handsome neoclassical town hall, several cafes and a public library. Everything you could want.

The library looked interesting. It occupies a 17th-century town house

gifted to Vilvoorde by the Lauwers-Van Ootegem family. I took a look inside. There were still traces of the original interiors, including stained glass windows decorated with portraits of Flemish artists. The library also extends into a more modern building with tiled walls that was once a meat hall.

The library is partly housed in a 17th-century building.

The library is partly housed in a 17th-century building.© André Thys

I had come to find out about William Tyndale. All I knew was that he was executed in Vilvoorde, and his final words were, ‘Lord, Open the King of England’s eyes.’ I was hoping the public library would have more information. But I could only find one book, a scholarly biography by David Daniell, founder of the Tyndale Society. I sat in the reading room, on the second floor of the old meat hall, reading the words of Tyndale’s last letter, written while he was being held in Vilvoorde Castle.

William Tyndale, Protestant reformer and Bible translator. Portrait from Foxe's Book of Martyrs.

William Tyndale, Protestant reformer and Bible translator. Portrait from Foxe's Book of Martyrs.© Wikipedia

‘I beg your lordship, and that of the Lord Jesus, that if I am to remain here through the winter, you will request the commissary to have the kindness to send me, from the goods of mine which he has, a warmer cap; for I suffer greatly from cold in the head, and am afflicted by a perpetual catarrh, which is much increased in this cell; a warmer coat also, for this which I have is very thin; a piece of cloth too to patch my leggings.’

This desperate, heartbreaking letter was written in Latin, possibly to the governor of Vilvoorde Castle. It is undated, but Daniell believes it was written in the autumn of 1535. It offers a glimpse of poor Tyndale shivering in a damp Vilvoorde prison while the authorities decided his fate.

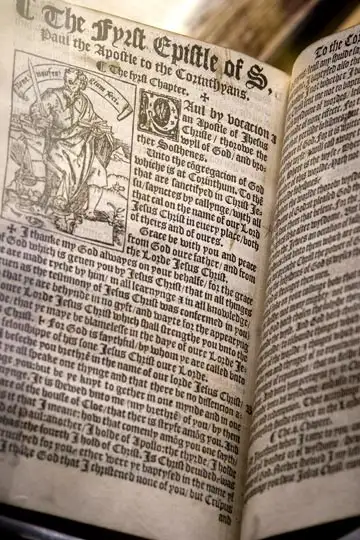

In 1526, William Tyndale’s first New Testament was printed in Europe and smuggled into England in bales of cloth.

In 1526, William Tyndale’s first New Testament was printed in Europe and smuggled into England in bales of cloth.© Houston Baptist University

William Tyndale was an English priest who spoke eight languages. He might have enjoyed a quiet life if he had not challenged the authority of the Pope by translating the Bible from Latin into English, so everyone could read it. His version, which he worked on in the 1520s and 1530s, introduced new words and phrases that, like Shakespeare’s, have become embedded in the English language. Tyndale came up with the words ‘atone,’ ‘scapegoat,’ and ‘sour grapes,’ as well as phrases such as ‘the meek shall inherit the earth,’ ‘the powers that be’ and ‘let there be light’. But Tyndale’s beautiful translation challenged the authority of the Catholic Church, and annoyed King Henry VIII of England. The powers that be weren’t pleased, you might want to say.

Tyndale was staying with the English merchant Thomas Poyntz in Antwerp when he was betrayed by Henry Philips, an English student at Leuven University. He was dragged off to Vilvoorde Prison where he was held for 18 months. Hilary Mantel naturally relishes recounting this grim story in her historical trilogy.

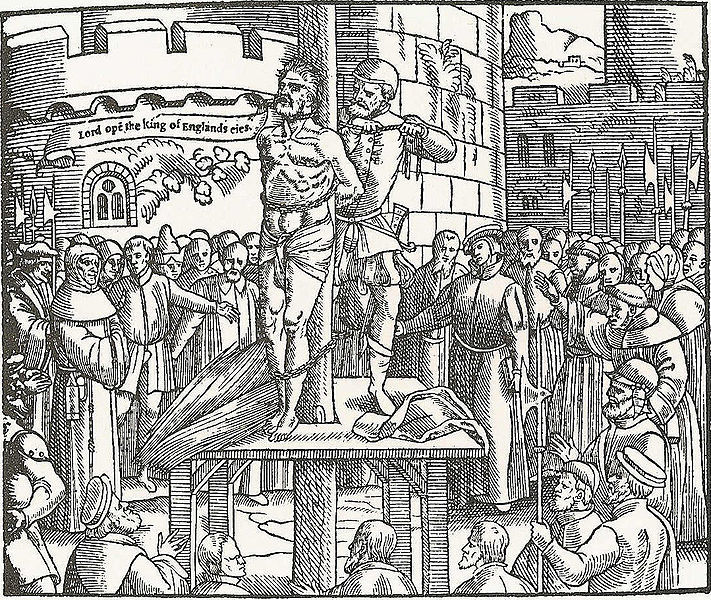

William Tyndale was strangled and burned at the stake in Vilvoorde because he translated the Bible into English.

William Tyndale was strangled and burned at the stake in Vilvoorde because he translated the Bible into English.© Wikipedia

I suddenly noticed the time. I had to hurry if I was going to catch the William Tyndale Museum, which is only open on Wednesdays from 10 to 12. The museum is located with a nice touch of irony in a former house of correction built near the site of the prison where Tyndale was held.

The William Tyndale Museum

The William Tyndale Museum© André Thys

The house of correction, or Tuchthuis, was built in 1776 as a model prison. One wing is now occupied by a hotel where you can spend the night in a former cell. No thank you, I thought.

© André Thys

Another wing is a crumbling brick pile and is classified. But the third wing has been carefully restored. The Tyndale Museum occupies a Protestant chapel on the ground floor. You reach it down a long corridor lined with small cell doors. One of the doors was open. I peered inside to see a tiny room lit by a narrow window. Now a storeroom where the clearers store their mops and buckets.

I could hear a booming voice in the distance. A church official was showing a visitor around the museum. He was describing the collection of bibles, prints and medals. Then he turned to Tyndale’s famous last (and only surviving) letter, the one in which he complained about the cold. It was apparently lost for three centuries, buried away in the local archives.

The museum didn’t have a large collection, just a few glass cases in a corner of the church. Mainly of interest to religious scholars. Out in the corridor, the walls were lined with historic prints and plans of the old castle, a grim fortress modelled on the Bastille in Paris.

I had picked up a folder that marked out a 1.5km Tyndale walk. It led me to the site of the castle, now a patch of grass next to the river Zenne. I thought of Tyndale shivering in his miserable cell, desperate for a woollen shirt, a night cap and a lamp. But most of all, he said in his letter, desperate to be given a Hebrew Bible, so he could carry on with his work.

The Tyndale walk continued past the church (still closed) and on to the William Tyndale Monument. I couldn’t find it at first. Then I saw a sign. Tyndaleparking, it read. They had named a city car park in honour of the English martyr.

The William Tyndale Monument

The William Tyndale Monument© City of Vilvoorde

Still looking for the monument, I turned down Hellestraat, which I thought must be Hell Street. And there was the monument, a sober column on the edge of a park. On it, in old-fashioned Dutch, the inscription read, Aan een Engelschman – To an Englishman. There were also versions in French and English. A metal plaque gave the grim details of his death.

The monument was put up in 1913. It is believed to stand on the site of Tyndale’s execution. But no one knows for sure. It is a rather sad spot. ‘Very dirty!’ someone has written on a review website. ‘Beer cans, bread and all sorts of rubbish lying around.’

Then someone spoke to me. It was the visitor from the Tyndale Museum. He was stuffing an egg mayonnaise sandwich into his mouth as he spoke. ‘It’s important,’ he said. I nodded. ‘We need to be able to read the Bible,’ he added. I noticed he had egg in his beard.

Which reminded me. It was time for lunch. I could honestly eat a horse.

What is paardenvlees? an American tourist asked the waiter.

‘It’s horse meat, sir.’

‘Horse meat, did you say?’

‘It’s a speciality of Vilvoorde. It’s very tasty.’

‘I think that might be illegal where we are from,’ the wife said.

Restaurant De Kuiper has been serving horse meat since 1859.

Restaurant De Kuiper has been serving horse meat since 1859.© Derek Blyth / City of Vilvoorde

It was a lunchtime in restaurant De Kuiper. I had gone there to try the horsemeat. De Kuiper is the place to go, I was told. This old Flemish restaurant is located in a quiet street called Vissersstraat, or Fishers’ Street. Established in 1859 by a horse butcher, it is now run by Alfons Gulickx and Lieve Gewillig. The interior is a nostalgic mix of old wood panelling, waxed tablecloths and a tiled floor. The horsemeat is fried in a pot of melted horse fat, then served with a bowl of frietjes. It is an old Belgian recipe. Delicious. And almost certainly illegal in the United States.

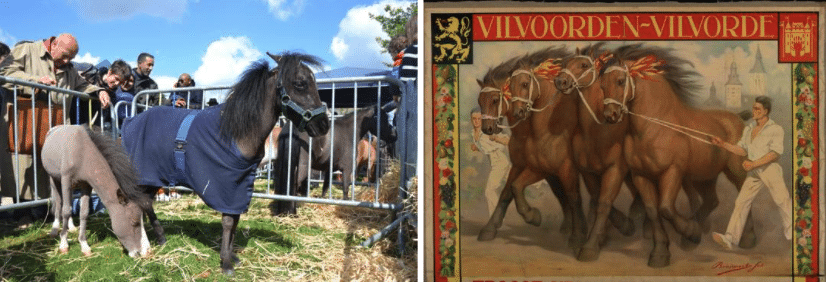

A huge mural on a side wall in Leuvensestraat celebrating Vilvoorde’s annual horse fair.

A huge mural on a side wall in Leuvensestraat celebrating Vilvoorde’s annual horse fair.© Derek Blyth

After lunch, I set off to find out more about Vilvoorde. The town is known locally as Pjeirefrettersstad, which means, ‘the city of horse eaters’. I had already noticed a statue of a horse in the middle of one of Vilvoorde’s many traffic roundabouts. I had also spotted a huge mural on a side wall in Leuvensestraat celebrating Vilvoorde’s annual horse fair. Held on the third Monday after Easter (9 May in 2022), the Jaarmarkt

is a sprawling agricultural festival that fills the streets with horses, but also cows, pigs and chickens, along with funfair rides, food stands and street games.

The horses that get paraded through Vilvoorde are big agricultural beasts called Brabantse trekpaarden, or Brabant carthorses. The former Belgian prime minister Jean-Luc Dehaene, who came from Vilvoorde, was sometimes referred to as the Brabants trekpaard because of his size and his dogged determination to get things done.

The Jaarmarkt is a sprawling agricultural festival that fills the streets with horses.

The Jaarmarkt is a sprawling agricultural festival that fills the streets with horses.© City of Vilvoorde

It struck me that a horse fair was an odd celebration, because Vilvoorde is not at all agricultural. It has been an industrial city since the railway arrived in 1835. In the early years of the 20th century, Charles Fondu was building cars to replace horses in a workshop next to the city park. But Fondu’s factory was small fry compared to the massive Renault factory under the Brussels Ring flyover. For a time, Vilvoorde was Belgium’s Detroit. But then it all went wrong.

The Renault car factory was the pride of Vilvoorde.

The Renault car factory was the pride of Vilvoorde.© City of Vilvoorde

On 27 February 1997, Renault suddenly decided to close down the massive car plant. In one day, more than 3,000 workers lost their jobs. The factory had been the pride of Vilvoorde. The workers protested and Belgians refused to buy Méganes. But Renault stood firm. In the aftermath, Vilvoorde became a grim, forgotten industrial city. Somewhere you drove over on the high ring viaduct on the way to somewhere else.

More than 20 years after the Renault factory closed, the city now has ambitious plans to redevelop the vast site. It will become a new urban quarter with housing, a hospital, concert hall and park, according to mayor Hans Bonte. But it will take 30 years to complete the project.

***

I was heading towards the canal. ‘You need to look at the area around the Kruitfabriek,’ someone had told me. ‘That’s where you find the new Vilvoorde.’ On the way there, I passed the Demol-Sphinx factory with the name spelt out in large red wooden letters. The brass sign on the door read, Manufacture de pinceaux et brosses à blancher J & P Demol.

The company was set up by local teacher Omer Demol in 1898 and taken over by his brothers Jules and Paul in 1920. It originally specialised in the manufacture of high-quality paintbrushes. When production moved partly to Egypt, the name Sphinx was added.

It looked as if Demol-Sphinx was still making brushes. But most of the other factories were abandoned. When the Forges de Clabecq closed in 1989, the city salvaged some of the old equipment to create an industrial heritage trail. The 14km route takes in 12 massive machine parts painted bright colours by local art students. Each machine has a QR code attached that explains its history.

© Derek Blyth

The heritage trail is a reminder that Vilvoorde was once one of the main industrial cities of northern Europe. Beginning in the 1850s, it attracted companies because wages were lower than in Brussels, and permits easier to obtain. But Vilvoorde is now definitely a post-industrial place looking for a new identity. It is already changing. A new neighbourhood is taking shape along the canal quays. Welkom in het Nieuwe 4 Fonteinen Stadskwartier – Welcome to the New Four Fountains Quarter,’ a sign announces. Smart apartments buildings are going up all along the waterfront. A new restaurant called Canal had the look of somewhere in London or Rotterdam.

The New Four Fountains Quarter

The New Four Fountains Quarter© Matexi

One industrial relic has survived. The massive abandoned Koekockx crane was meant to be shipped to Congo, but never left Vilvoorde, and now stands as a symbol of the city’s proud industrial past. Further along the canal, the Kruitfabriek or Gunpowder Factory is another solitary relic from the industrial age. It stands on the site of a 19th-century explosives factory that was used by the German army to store weapons during the First World War. Abandoned after the war, the arms dump exploded in 1919, destroying dozens of houses, and shattering the stained glass windows in the town hall.

The Koekockx crane stands as a symbol of Vilvoorde's proud industrial past.

The Koekockx crane stands as a symbol of Vilvoorde's proud industrial past.© André Thys

Several new factories were built on the site. But they all eventually closed down. A few of the abandoned buildings were taken over by Flemish media organisations, including Woestijnvis TV production company and Humo magazine. The TV company VTM settled on the edge of Vilvoorde and the Big Brother house was built nearby in 2020.

The Kruitfabriek opened in 2014 in one of the abandoned factories. It is now occupied by a hip coffee bar and roastery called GAYO, circus workshop, music school and craft studios. The site is a lively creative hub at the weekend when there are workshops, concerts and vintage markets.

Around the back of the factory, I discovered a stretch of the river Zenne. This sad little river runs through Brussels in a 19th-century tunnel. But it returns to the surface in Vilvoorde. The city recently created a walking and cycling trail that follows the meandering river in the direction of the old prison. It makes an interesting route back to the city centre.

I was starting to wonder if Vilvoorde might have turned itself into a city of the future. It is the fastest growing town in Belgium with something of the spirit of Detroit and something of the mood of Berlin. It has a waterbus linking it to Brussels, along with a brand new cycle superhighway that runs along the canal.

The river Zenne runs through Brussels in a 19th-century tunnel, but it returns to the surface in Vilvoorde

The river Zenne runs through Brussels in a 19th-century tunnel, but it returns to the surface in Vilvoorde© Paul Van Caesbroeck

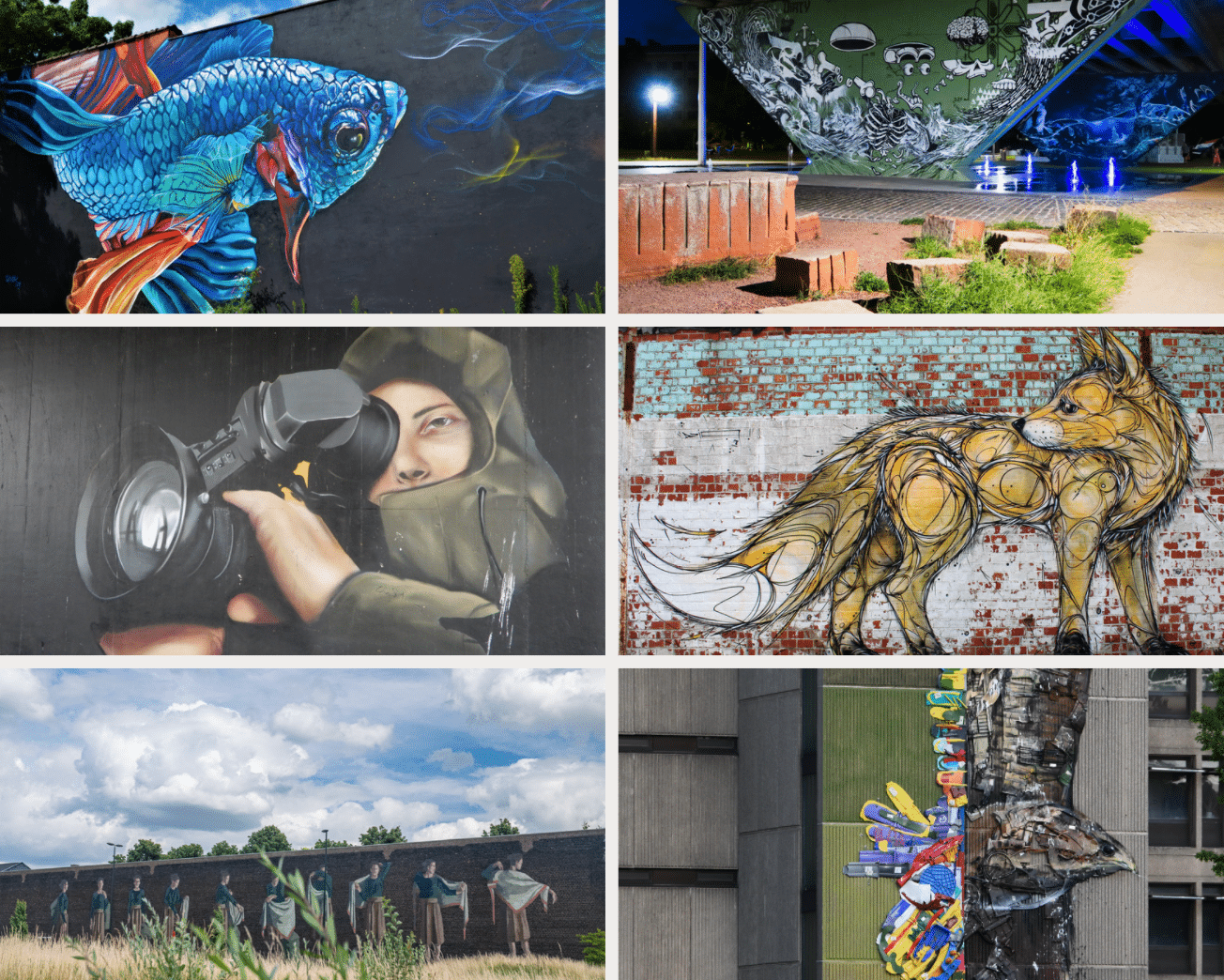

The city also has more than 50 murals by Belgian and international street artists. The artists have decorated dead walls all over town as well as the concrete pillars of a modern bridge, the Europabrug, that soars high above the canal. There is a 10km street art tour that guides you to unexpected locations including a wall where the artist HYURO has created a beautiful series of figures that represent the arrival of Spanish immigrants in Vilvoorde.

There are other inspiring spots, including a wall next to the local art school in Vaartstraat. In the summer of 2020, art students were invited to turn the grey concrete wall into a photo gallery dedicated to Vilvoorde. The images include abandoned factories and ugly cooling towers, but also smiling children and romantic parks. The portraits reveal the mix of nationalities that have grown up here as a result of migration.

Vilvoorde has more than 50 murals by Belgian and international street artists.

Vilvoorde has more than 50 murals by Belgian and international street artists.© City of Vilvoorde

A few years ago, Broeilab was launched to encourage creative new businesses to take over empty shops. This project has so far launched 25 new businesses selling everything from kids’ clothes to flowers. You can often spot these places by their quirky names. The Sweety Cake cafe serves coffee and cake in a historic building on the main shopping street, Fietsenier sells cool bicycles, and Spolly’s Ting is crammed with restored old furniture.

It is unclear what the original function of the Kijk-Uit was. In 1975, the building was classified as a monument.

It is unclear what the original function of the Kijk-Uit was. In 1975, the building was classified as a monument.© ArcheoNet Vlaanderen / Tijl Vereenooghe

But there are still some empty buildings in the centre. I was intrigued by one abandoned brick building behind the town hall with a strange lookout tower. The building is called Kijk-Uit, or Lookout. And no one can explain the building. Some believe it was a watermill. Others claim it was a lookout tower. It became a bar in the 19th century, but now lies empty. The building was bought by a hotel chain.

Further down the street, three friends opened a striking coffee bar and lunch spot in 2020. They have converted a corner building that was once a bank into a bright, contemporary cafe called Stoom with big windows looking out on the street. And there’s a surprise in the basement where they have created a kids’ playroom inside the bank’s vault.

I sat in Stoom trying to figure out a word to describe Vilvoorde. It brands itself on its city map as gastvrij, gezellig en vernieuwend, or friendly, charming and innovative. Which could be anywhere. Pjeirefrettersstad was another word that might define the town. But that didn’t quite cover it.

Back at the canal, I tried to decide if Vilvoorde could ever become a tourist destination. Already, there are tour boats in the summer that leave from the Kanal art centre in Brussels and drop people off near the crane. Tourists could pick up a barista coffee at Kruitfabriek, admire the contemporary architecture, and wander into Vilvoorde along the Zenne. It might work if there was a castle or museum to visit. But the castle was demolished and the museum is only open on Wednesday mornings.

The Drie Fonteinen Park (Three Fountains Park)

The Drie Fonteinen Park (Three Fountains Park)© Wim Robberechts

Then someone told me about the park on the other side of the canal. ‘It’s a lovely place for a ramble,’ he said. Back in the 19th century, several wealthy Brussels families built elegant summer villas next to the canal surrounded by landscaped gardens. Three of these estates have been merged to form the Drie Fonteinen Park

(Three Fountains Park). The odd name comes from a fountain that stood next to a lock. It had four water jets to symbolise the four winds, but skippers on the canal could only see three at any time.

The park lost some of its charm when the Vilvoorde viaduct was constructed as part of the Brussels Ring motorway. But it still has romantic bridges, hidden lakes and a sublime Japanese garden. There is also a lively brasserie located in a former orangerie. Somewhere to go for lunch on a Sunday.

The Japanese garden in the Drie Fonteinen Park.

The Japanese garden in the Drie Fonteinen Park.© André Thys

I had one neighbourhood still to visit. It has the intriguing name Far-West and features in a song by the folk singer Kris de Bruyne, who died in 2021. O Vilvoorde City, he sang in 1975, meer bepaald in de Far West – more precisely in the Far West.

The city map marks Far-West, although the location looks like it is Far East. But anyway, it sounded intriguing. Will I see cowboys? I wondered. The district is reached through a tunnel under the railway tracks, where street artists have painted Wild West scenes. And yes, there is a cowboy.

Far-West turned out to be a neighbourhood of neat little houses with front gardens. It was created in the 1920s as a model garden city. And yet it used to be a rough spot. Kris De Bruyne lived there for five years in the early 1970s. Hier hangt de lucht vol weemoed – The air here reeks of sadness, he sang. En de stank is om te snijden – And you can cut the stench with a knife. As if that was enough, the neighbourhood was more recently linked to Islamic terrorists.

In an interview, De Bruyne said he wrote the song in Ture’s Drinkwinkel in Olmstraat. It was a love song, he explained. He wanted to make a recording in the town hall. But the mayor, when he heard lyrics, said no. It would cast Vilvoorde in a bad light, he insisted.

‘I didn’t write it to badmouth Vilvoorde,’ De Bruyne said. ‘It was a metaphor for my feelings after my relationship broke down.’ But the mayor refused to change his mind. And you can maybe see his point.

Then I discovered that the city doesn’t end at Far-West. There is somewhere further. And wilder. Far Far-West, you might say. The Asiat site was once a military base squeezed between the river Zenne, a recycling park and the town cemetery. The army moved out in 2008, leaving behind abandoned sheds, workshops and barracks. In the summer of 2019, this overgrown wilderness was taken over by Horst festival, formerly based at Horst Castle.

Horst festival

Horst festival© Olmo Peeters

The organisers transformed the industrial badlands into a summer festival site dotted with deckchairs, pop-up cafes and playgrounds. There were techno concerts and art shows amid the menacing cooling towers and ruined barracks. It was a success and Horst is now a cool annual festival that brings thousands of music and culture fans to a forgotten corner of Belgium.

O Vilvoorde city, you’re not as sad as they say.

This article was realised with the support of the Flemish Government.