House of European History Celebrates a Continuously Evolving Continent

When you talk about Europe, what are you actually referring to? The entire continent as it was defined by the geographic community, or merely the 27 member states of the European Union (EU)? What makes us Europeans? Do we have a shared history? Which perspective do we take when we talk about that past? All of those questions are dealt with in the House of European History in Brussels. Although the museum does not offer a set of cut-and-dried answers, you will come away from it realising that Europeans have more in common than they might initially think.

The museum is situated in the Leopold park, at the heart of the European Quarter, in the prestigious Eastman building, a former dental clinic. Visits can be experienced in all 24 (!) official EU languages and admission to the museum is free of charge.

Do not expect to find ready-made answers to earlier questions. What you will experience, however, is a journey – rich in imagery – through the history of countries and peoples, which, for various reasons, feel connected in time and space. The stories we share, the conflicts that left a mark on Europe, our heritage and past traditions, as well as our future challenges.

Self-promotion?

It took several decades to create the European Union as we know it today. During that process, the way many European countries were organised and governed was also transformed. The generation who lived through the twentieth century’s tragedies and founded the consecutive European Communities is gradually disappearing. Therefore, there is a certain urgency about sharing the development of the European integration in a way that is easy to understand and accessible to a broader audience. The House of European History puts it as follows in its mission statement, ‘In times of crisis, it is particularly important to develop and sharpen consciousness of cultural heritage and to remember that peaceful cooperation cannot be taken for granted.’

Nevertheless, putting this mission into practice faces criticism within the EU as well. Isn’t this rather pricey poster child of the European Union mainly aimed at self-promotion? Indeed, opinions are divided about a number of fundamental aspects of European history. Certain facts related to World War II, for instance, or the role the United States played in post-war Europe. How can we shed light on those aspects from a neutral, cross-border perspective?

Mythical princess

Peter Paul Rubens, The Abduction of Europa, 1628-1629, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Peter Paul Rubens, The Abduction of Europa, 1628-1629, Museo del Prado, Madrid© Wikipedia

However, let’s start at the very beginning, on the second of the in total six floors. There, you step right into the continent’s history with the story of Europa, the mythical Phoenician princess, who was abducted by Zeus (in the form of a white bull) and gave her name to the continent of Europe.

Straight away, we learn about the European interest in maps, a fascination that goes back to ancient Greece and Rome. When the maritime routes to North and South America were discovered in the fifteenth century, Europeans were not only given a different perspective on the world as they knew it, but they also started to see themselves in a different light.

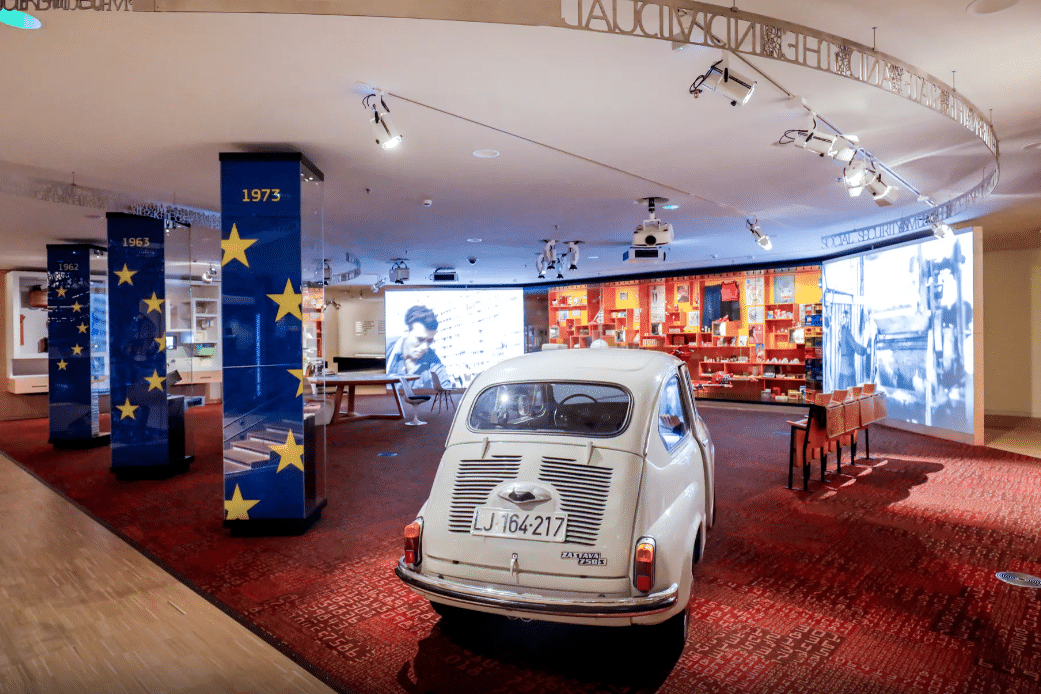

During our visit, we climb the stairwell, in pursuit of a winding word garland made from paper-thin metal, which moves through time, right to the very top of the building.

At the core of the museum lies the permanent exhibition. Do not expect to be told separate stories from various European countries and regions. Instead, the museum focuses on larger phenomena or movements that have left their mark on the continent. To achieve this focus, an academic project team established three criteria: the origins of the event or idea must lie in Europe, the event or idea must have spread throughout the entire continent and must continue to be relevant today. Topics that are dealt with are both World Wars, the Cold War, the Europe of the Regions, nationalism and identity, heritage and continuing European integration. Occasionally, the permanent exhibition ventures outside of Europe’s boundaries.

The House of European History does not want to be a simple cumulation of national histories either, nor does it wish to replace those

The emphasis is placed on the European story in the nineteenth and twentieth century. During this period, Europe’s course radically changed because of the growing desire for democracy and national sovereignty, as well as expanding industrialisation and imperialism. At that time, Europe reached the peak of its global power. The changes in nineteenth-century Europe caused social unrest, which still resonates today.

The House of European History does not pay much attention to anecdotes, although, once in a while, personal stories do make an appearance. Those stories help shape the human experience behind the displayed artefacts. The beautiful scenography in the museum space is characterised by a lot of variation and perfectly matches the time period and events on display, encouraging a lot of interaction and multimedia immersion.

During a visit to the museum, the same questions pop up time and time again. What is truly of European origin and has spread throughout the continent? Which aspects of our European heritage should we preserve, what do we want to change, and what must we oppose? And what is even more pressing and tricky: does the House of European History want to create a European identity? The museum, however, explicitly does not wish to take such a reductionist and static view as its point of departure. However, it does not want to be a simple cumulation of national histories either, nor does it wish to replace those.

The museum predominantly considers itself as a reservoir for European memories, in which several experiences and interpretations are united, while paying attention to all of their diversity and contradictions, with a focus on the emergence of the European Community. Topics such as Brexit or the Greek austerity measures are only addressed briefly. Situated not far from the House of European History, the Parlamentarium, the European Parliament’s visitors centre, supplements the museum, by having the role, operations and activities of the European Parliament take centre stage.

Critical outlook towards the future

The objects on display in the House of European history originate from museums all over the world. They provide insight into the way other cultures perceived Europe and the Europeans. For instance, there is the image of a wealthy continent, of European countries as colonial powers, which – by means of oppression, slavery and exploitation – dominated the main part of the world. This aspect of Europe is not completely ignored in the museum, but it might be too emphatically labelled as ‘part of a distant past’.

How do Europeans look upon themselves today? When they close their eyes, what picture do they see of the ‘old continent’ and what do we expect of an institution such as the European Union? The final room on the sixth floor offers plenty of space for (self-)reflection and encourages questions as well as well-founded criticism. It is a shame, though, that it is unclear what actually happens with that feedback.

#makecovid19history

The House of European History is most valuable because of its educational qualities. It aims to reignite the public debate about European memory and awareness. For that reason, the museum obviously wants to be up-to-date. Using the hashtag #makecovid19history, in March 2020, the museum launched a project collecting testimonials of live in Europe during the Covid-19 pandemic. The documentation that was collected emphasises hope and the sense of community that was born out of this period. That way, a very topical temporary exhibition was created.

The House of European History keeps a record of a moment in European history while it is still being written

The coronavirus crisis is probably the largest European (and, of course, global) event since the Cold War, of which the consequences will remain visible for a long time to come. Although experiences and coping strategies might be different from country to country, or from region to region, many recognisable scenarios and stories form a common thread throughout the European continent. The museum, for instance, pays attention to basic human rights during lockdown, to solidarity, to the accomplishments of medical staff and the citizens’ resilience.

In doing so, the House of European History keeps a record of a moment in European history while it is still being written.