How a Small Dutch Island Lay at the Cradle of the United States of America

St. Eustatius, popularly known as ‘Statia’, is now a little known island in the Dutch Antilles, but it played an important role in America’s War of Independence. When war broke out in 1775, the island’s merchants provided weapons to the rebelling American settlers, and thus made an important contribution to their eventual victory. When the governor of St. Eustatius ordered a rebel warship to be saluted, the Americans considered this the first recognition of their independence. In his book The Golden Rock, Willem de Bruin tells how a tiny island was assigned a key role in world history.

On the map it is no more than a dot in the Caribbean Sea, about 35 kilometres south of the popular and bigger St. Maarten: St. Eustatius. Only neighbouring Saba is a little smaller still. St. Maarten usually needs little introduction. It has been a popular holiday destination for decades. Picturesque Saba makes up for its lack of beaches with its lush tropical vegetation. In the shadow of these two Dutch islands St. Eustatius leads a somewhat forgotten existence.

St. Eustatius or Statia, as the locals call their island

St. Eustatius or Statia, as the locals call their island© Cees Timmers Photography

Sparsely vegetated and devoid of golden beaches, this far corner of the Kingdom of the Netherlands does not invite a visit at first glance. Yet this impoverished island boasts a fascinating history. Until the end of the eighteenth century St. Eustatius was known everywhere as the ‘Golden Rock’. At one point it was the most prosperous island in the western hemisphere, a cosmopolitan meeting point where everything the world had to offer, legal as well as illegal, could be bought. St. Eustatius was able to fulfil this role due to its favourable location and its status as a neutral free port, at a time when other colonial powers were often in conflict with each other.

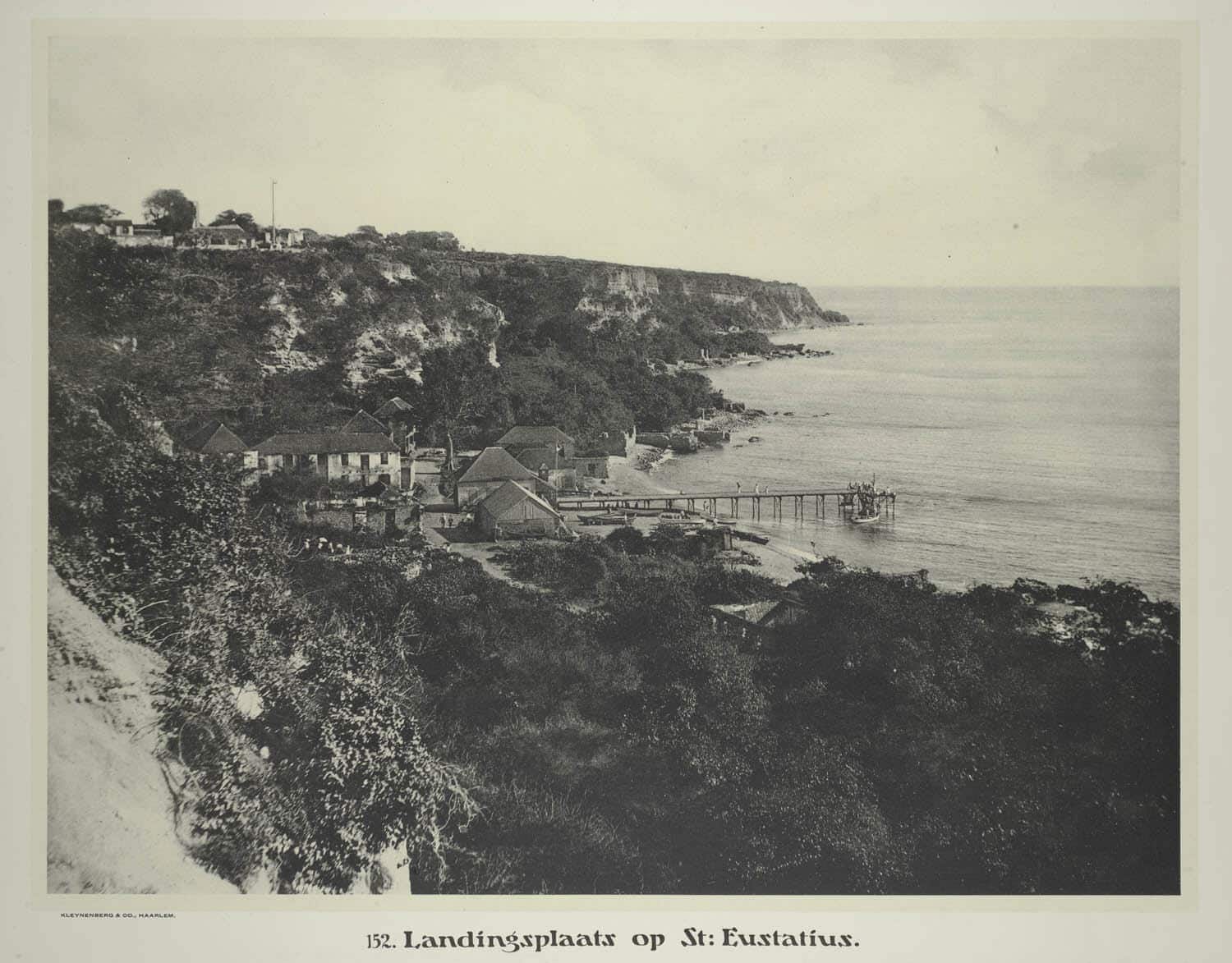

Oranje Bay in 1913

Oranje Bay in 1913© Dhr. J. (Jean) Demmeni / Collectie Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen

It is not hard to find traces of this rich heritage, although not every visitor will be able to recognise them immediately. For example, the ruins along the island’s natural port, Oranje Bay. Often there is no more than a crumbling wall that protrudes into the water from the bank. Sometimes the outlines of the building which must have stood there are visible. Half way along the bay the remains of a boat landing has almost disappeared into the sea. Visible on the other side of the road along the water, half hidden under trees and exuberant vegetation, are yet more remains of buildings that disappeared a long time ago.

Barely a dozen buildings still stand along the two-kilometre bay, most of them hotels that cater for the modest number of diving tourists who visit the island – it is surrounded by around 200 shipwrecks. All in all, this narrow coastal strip can barely justify its name ‘Lower Town’. Very few visitors climb up to the top of the 40 meter cliff which towers directly behind the buildings and forms a natural barrier between the Lower Town, and the from there invisible Upper Town. A path which has been cut into the cliff face saves pedestrians the detour that drivers are forced to make in order to get up there. The path reaches the top only about a hundred metres from the picturesque Fort Oranje which balances on the edge of the cliff. Since 1636 the Fort has been symbolic of Dutch authority over St. Eustatius. A small settlement grew surrounding the fort, which in contrast to the Lower Town has largely remained intact. Here the buildings are dominated by wooden houses, which in many cases still date to the eighteenth century. If it were not for the cars, the surroundings of Fort Oranje make it possible to imagine oneself in the time of the West India Company.

Fort Oranje

Fort Oranje© John Peltier

Over the course of the eighteenth century a downward leap was taken and the Lower Town developed at the bottom of the cliff. At its peak it comprised hundreds of warehouses, shops, inns, bars and brothels. The warehouses contained tropical products that came from the region’s islands – coffee, cocoa, sugar, rice – as well as tobacco and wood from North America and luxury products from Europe. There were almost always tens of ships from every corner of the world anchored in the bay, waiting for a time to unload their cargo or take a new load on board. In the 1770s St. Eustatius received as many ships as Amsterdam – around three thousand per year.

In the 1870s St. Eustatius received as many ships as Amsterdam – around three thousand per year.

In the 1870s St. Eustatius received as many ships as Amsterdam – around three thousand per year.© St. Eustatius Historical Foundation

Whilst England and France were trying to keep trade with their colonies in-house, any ship was welcome in St. Eustatius. Merchants were often able to sell their wares at a higher price than in other places, which in defiance of their monopoly also tempted English and French merchants to set sail for the Dutch island. This meant that alongside legal trade, a smuggling trade became at least as extensive.

The opportunities that St. Eustatius offered to get rich quickly invited ever-greater risk taking. Risks that would eventually prove fatal for the island. In 1775 British settlers in North America revolted against the government in London, marking the beginning of the American War of Independence. It was very important for Great Britain to prevent George Washington’s rebel army from being supplied with weapons and ammunition. Both France and the Netherlands were happy to deliver these, but direct supply from Europe quickly became too dangerous. The solution was to first send ships laden with gunpowder, often packed as rice or sugar, to St. Eustatius, where the cargo was transferred onto American ships. This barely disguised illicit trade led to indignant reactions from the British. On paper, the Republic of the United Netherlands was still an ally of England. The fact that the Hague denied knowledge of any such activity was becoming increasingly unbelievable.

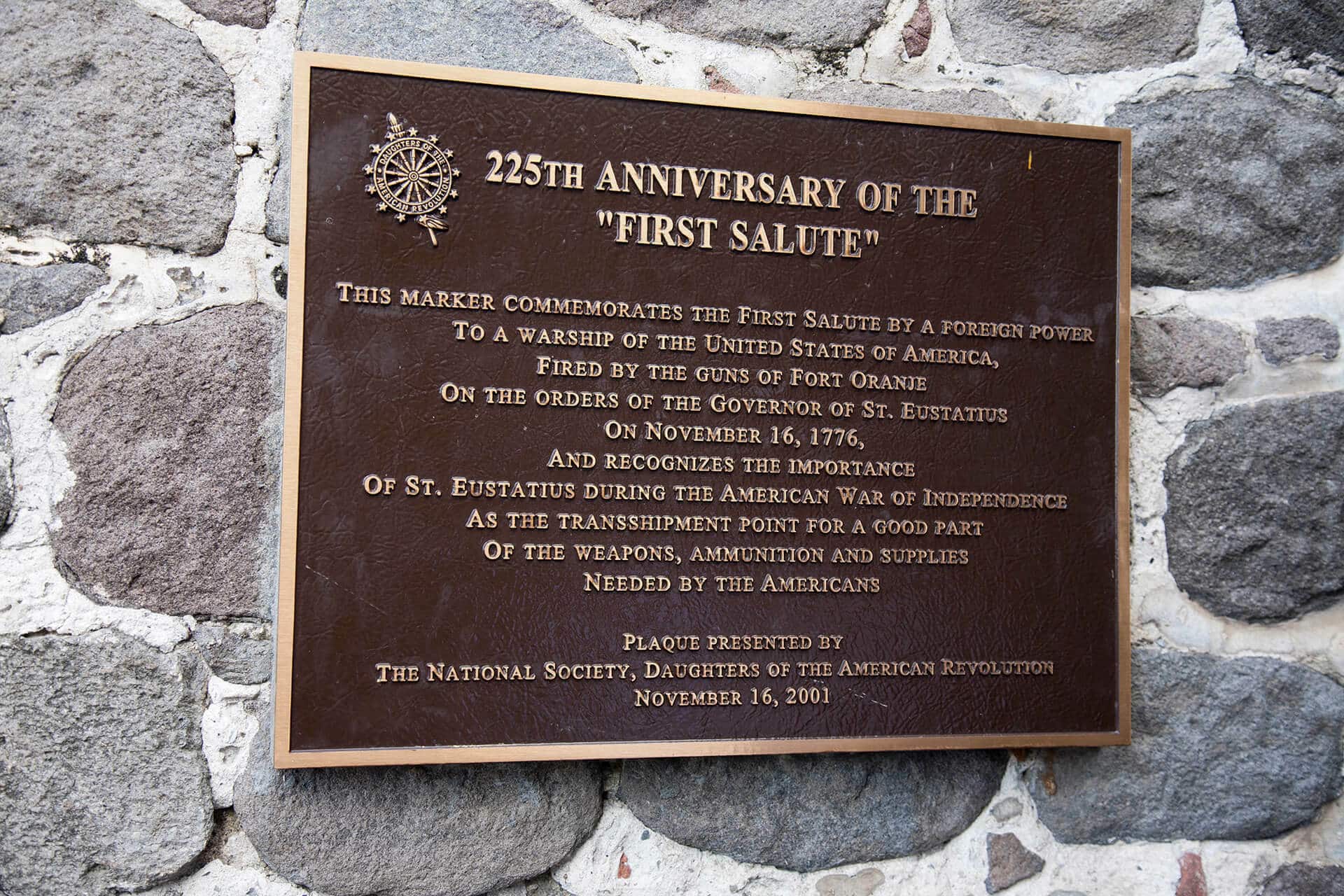

Plaque commemorating the First Salute

Plaque commemorating the First SaluteThe suspicion that the Netherlands was two-timing was bolstered when for the first time on 16 November 1776, an American warship, the Andrew Doria, cast her anchor in St. Eustatius’ bay, and was greeted with a gun-salute from Fort Oranje. The new flag of the United States of America flew from the main mast. The rebels had declared their independence a few months earlier, but nobody had yet recognised the new state. This gun-salute would therefore go down in American history as ‘The First Salute’ – the first public recognition of their independence from a European power. In the eyes of the British, this was a provocation of unheard proportions and yet more proof of the Republic’s dishonesty. After years of ever-increasing tensions, the situation came to a head at the end of the 1780s and Great Britain declared war on the Netherlands. The first objective of the war was obvious: St. Eustatius.

St. Eustatius was taken by the English fleet in February 1781. The island was pillaged by the troops of George Rodney.

St. Eustatius was taken by the English fleet in February 1781. The island was pillaged by the troops of George Rodney.‘The wealth on this island is beyond imagination’, the British admiral George Rodney wrote to his wife after the occupation of St. Eustatius on February 3rd 1781. The completely surprised Dutch governor Johannes de Graaff of the barely defended island could do little more than surrender unconditionally.

Admiral Lord George Rodney (1719-1792), 1791, painted by Jean-Laurent Mosnier

Admiral Lord George Rodney (1719-1792), 1791, painted by Jean-Laurent Mosnier© National Maritime Museum, London

Rodney was highly regarded as Fleet Commander but his private life was altogether more questionable. It was a well known secret that the admiral had extensie gambling debts. At that time, a Fleet Commander was entitled to a large part of the spoils of war, and the order to invade St. Eustatius could not have come at a better time for Rodney. This was a chance to rid himself of his debts in one fell swoop. His greed, however, came at the expense of his vigilance. While the admiral was busy securing the contents of the warehouses, a large French fleet was approaching from the Atlantic Ocean. The British Supreme Command feared that these warships would sail via the West Indies to North America, where they could shift the military balance in favour of the rebels. That was the right assumption, but unfortunately Rodney reacted too late to stop the French.

It was not the only setback that the English would have to deal with. Shortly after Admiral Rodney sent the bulk of the spoils to England by ship – and sold the rest by auction – French troops from Martinique carried out a surprise attack on St. Eustatius. This time it was the British, who were surprised in their sleep, that had to surrender. The capture of St. Eustatius had resulted in bringing British defeat only closer.

St. Eustatius flourished again for a little while but at the end of the eighteenth century, during the aftermath of the French Revolution, the island once again became a toy for the world’s great powers and the Golden Rock came to its end forever.