How Amsterdam Became the Bookshop of the World

In the 17th century, Amsterdam was a mecca for book lovers from all over the world. On how the Dutch Republic satisfied the hunger for reading at the time, historians Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen have written The Bookshop of the World, a ground-breaking, staggering and provocative book.

The Bookshop of the World

allows us to distil a wonderful list of superlatives: at least three hundred and fifty thousand different books, pamphlets, newspapers and official documents were printed in the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth century, totalling more than three hundred million copies all together. In relation to the number of residents, Dutch printers and publishers produced ten times as many books as their colleagues in France, Italy and Spain, countries which at that point belonged to Europe’s cultural vanguard. The Germans kept up with the Dutch a little better, but were still behind by a factor of five. For a few decades now, library catalogues have been linked, making it possible, with certain reservations, to construct these kinds of quantitative insights. But if we know this, how can we explain it?

The Mark Zuckerbergs and Jeff Bezos of the seventeenth century were Cornelis Claesz., Broer Jansz., Willem Jansz. Blaeu and Daniël Elzevier, daredevil innovators who in a short time developed an enormous dominance in the market and earned a great deal of money. Knowing how to make an attractive book is one thing; optimally managing the costs is another; but the secret of the Dutch publishers is their skill in building up distribution networks. Dutch books move at lightning speed to all corners of Europe. And books from elsewhere surfaced in the bookshops in the large cities of the Republic. Around 1600, Amsterdam became a mecca for book lovers from all over the world, a position the city has never completely given up.

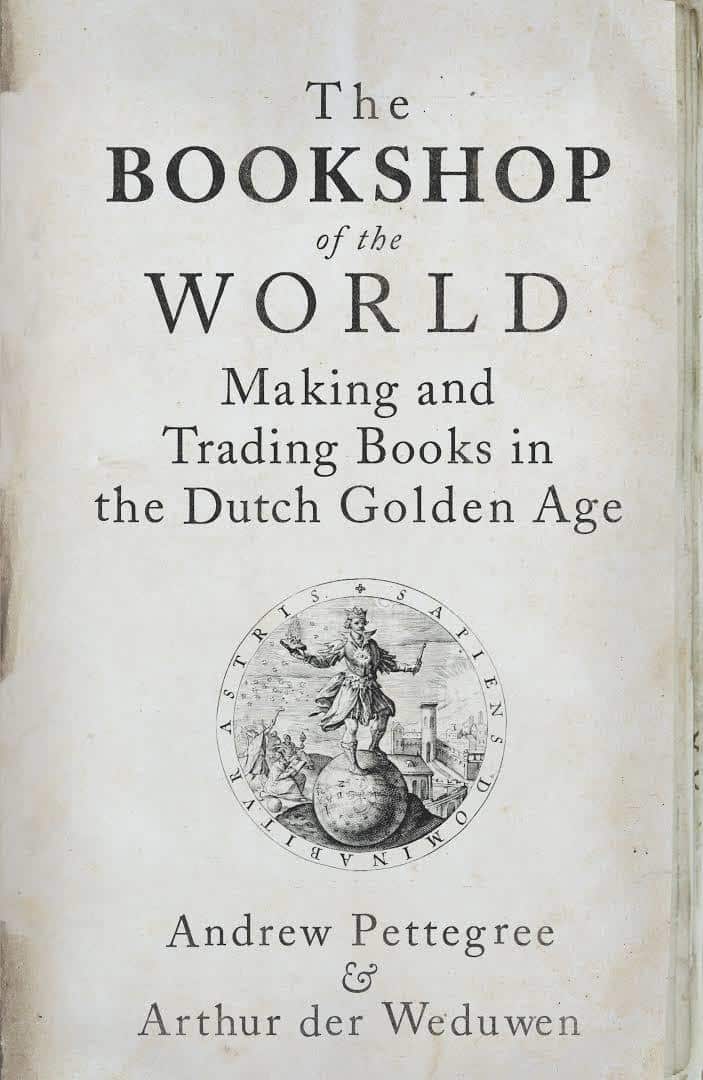

A Dutch book printing office in the mid 17th century, engraved by Abraham von Werdt (1594-1671)

A Dutch book printing office in the mid 17th century, engraved by Abraham von Werdt (1594-1671)Detectives

It’s an attractive thought, that in these years books were what made the Republic stand out from the rest of Europe, and that’s also the view of Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen, based on an astonishingly multifaceted study. Catalogues, archives, journals, letters and in the end the seventeenth-century printed material itself was turned inside out, in search of information as to how it was all traded and used in everyday life.

Andrew Pettegree is well established as an expert in the religious movements of the sixteenth century and as an author of magnificent panoramas of the history of the book, such as Brand Luther, four years ago, about Luther’s effective use of the printing press to disseminate his ideas, a book which has already achieved classic status.

Dutch gardening manual, late 17th century

Dutch gardening manual, late 17th century© New York Public Library

Arthur der Weduwen, like Pettegree working at the prestigious St Andrews University in Scotland, gained his PhD two years ago with a weighty dissertation providing an inventory of production of Dutch newspapers between 1618 and 1700. Dutch newspaper publishers became increasingly skilled at satisfying the public’s constant hunger for news, and thus set an information revolution in motion. The Bookshop of the World, which was published this year in both English and Dutch, continues to work on the idea that Dutch publishers know how to set up a well-oiled machine.

As detectives Pettegree and Der Weduwen went in search of sometimes very sketchy traces of the ephemeral printed material of the seventeenth century. Dusty, almost untouched local archives turned out to be an important source of printed government publications, and auction catalogues supplied a wealth of information about books which have meanwhile gone missing.

The less a book was loved and read, the greater its chance of survival

Foreign archives turned out to be a surprising repository of Dutch newspapers; domestically they were readily passed on and read until they were worn out, ending up as toilet paper, whereas abroad they were retained by some diplomats and civil servants as an information source.

For many books and newspapers, only one copy is known, and a great many have disappeared forever. The less a book was loved and read, the greater its chance of survival. Pettegree and Der Weduwen see books primarily as consumer products and less as collectors’ items for the elite with high purchasing power.

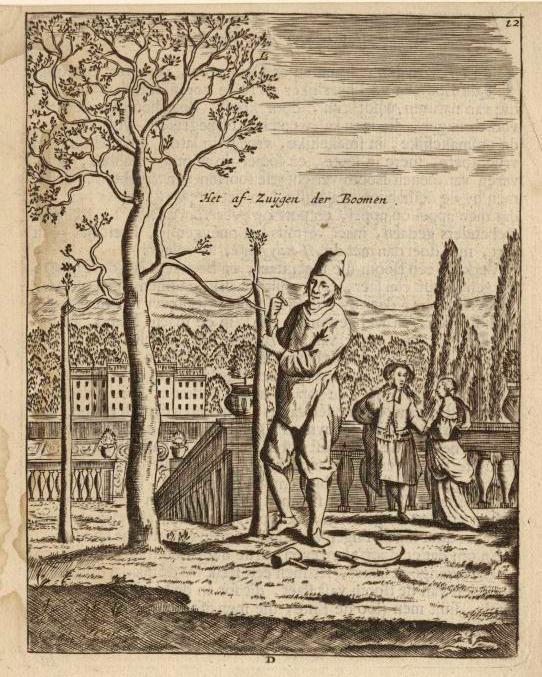

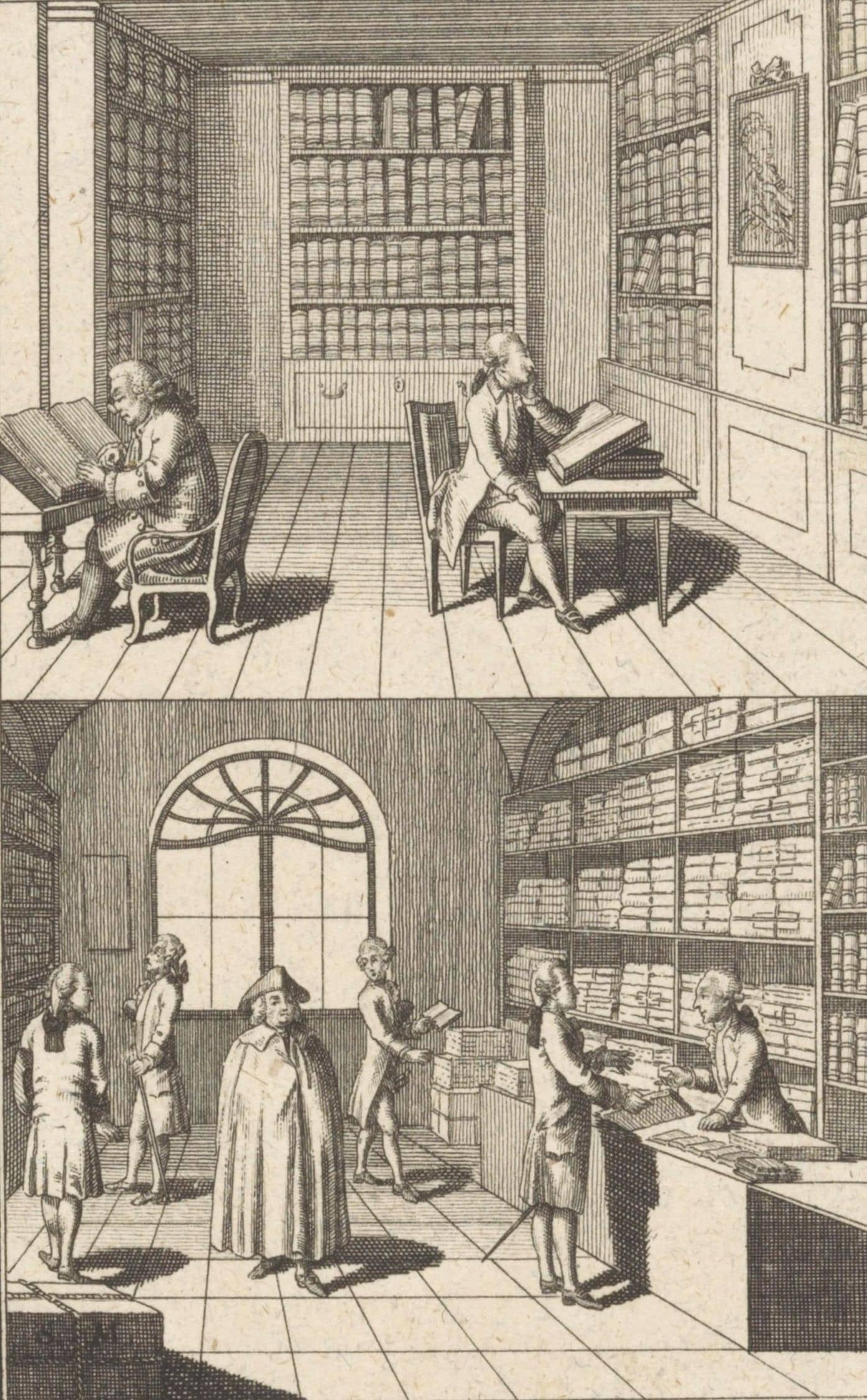

17th century library and book shop in Amsterdam by Monogrammist SIM, 1700 - 1799

17th century library and book shop in Amsterdam by Monogrammist SIM, 1700 - 1799© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Through various chapters we follow successful, less successful and sometimes outright clumsy printers, publishers and book traders (overlapping activities during this period) in search of gaps in the market. We discover how, in the wake of the Dutch voyages of discovery, the travel log became a great success, and how the need for religious texts was satisfied with a varied stream of hymn books, catechisms and bibles.

Often Dutch entrepreneurs succeed in awakening a latent need, as in the case of Elzevier with his editions of classical texts in pocket book format (the forerunner of current pocket books), which were sold all over Europe. It became an indication of a certain lifestyle to pull out your Cicero or Suetonius while travelling or in company.

Provocations

The Bookshop of the World

contains several ground-breaking chapters, including one about the rather cyclical trade in atlases and travel books, the chapter about the more stable and insatiable market for religious printed material, or one about the opportunistic market for pamphlets, where in times of political tensions it was sometimes very easy to earn money. Beautifully written, glittering with magnificent details.

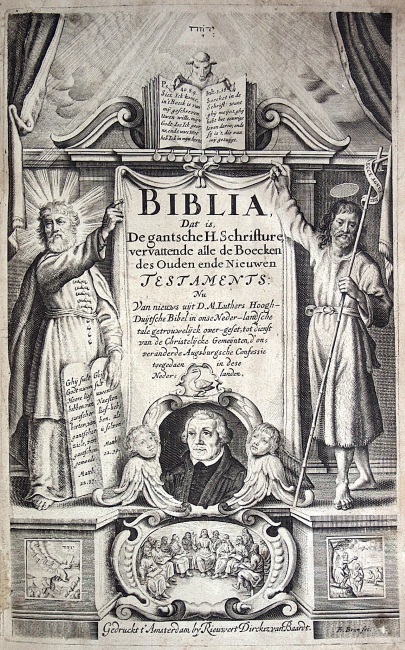

Dutch edition of the Luther Bible, published in 1648 by Rieuwert Dirksz van Baardt in Amsterdam

Dutch edition of the Luther Bible, published in 1648 by Rieuwert Dirksz van Baardt in AmsterdamParticularly sublime is the chapter about the multifaceted book business around the Dutch universities, with the remarkable fact that of tens of thousands of dissertations defended there in the seventeenth century, more than half are probably lost. The book is also a great stimulus for further research, particularly the title chapter, about the many off-shoots of the Dutch book world in the rest of Europe.

Nevertheless there is something unbalanced about the book. Once in a while the authors go on the rampage almost without warning. For instance on the production of news prints: ‘Michiel de Ruyter, in particular, was a favourite subject. His rotund appearance (he was the son of a beer transporter) seemed to be a guarantee of his unwavering republican stance.’ Since when have historians derived a person’s character and views from their appearance and background? Where does this strange stereotype come from? In any case, it’s nonsense. Even more colourful is the judgement of Coornhert as an ‘embittered revel’, who was driven to ‘vanity’. Tut tut.

Pettegree and Der Weduwen enjoy a bit of provocation. For instance they begin their weighty study with a substantial exaggeration. They claim that ‘in the classic success story of the Dutch Golden Age’, books and the book trade ‘somehow or other have been swept under the carpet’. That claim cannot be maintained. To name just one counterexample, take the monumental work 1650 Bevochten eendracht (‘1650 competitive harmony’) by Marijke Spies and Willem Frijhoff, in which books and their makers more or less form the cement of an integral cultural history.

Johannes Lingelbach, View on the Dam in Amsterdam, 1656

Johannes Lingelbach, View on the Dam in Amsterdam, 1656© Amsterdam Museum

Dutch book studies have been flourishing for more than half a century, and the study of the long Golden Age, from around 1550 to 1700, is the heart of the subject. Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen wouldn’t have been able to write their study without all that research and all those attempts at synthesis by their colleagues.

But it must be said, the subject has rarely been exhibited in the way that they tackle it. A great many assumptions that have crept in over the past decades in the cultural historical approach have been dismantled. The book business didn’t rely on trading the work of Hooft, Vondel and Spinoza, but on anonymous collections of hymns, government proclamations, newspapers and certainly a great many bibles and catechisms. In the end it’s a question of the book business of a world that was still very religious.

Andrew Pettegree & Arthur der Weduwen, The Bookshop of the World. Making and Trading Books in the Dutch Golden Age, Yale University Press, 2019