How Belgium Helped Shape the British Identity

From Waterloo to the Westhoek, the Belgian soil is full of British corpses. Professor of English Literature and Culture Marysa Demoor has explored the very close links between the two nations; links that could even be considered decisive in the development of British identity. The relationship was not always completely cordial: often, in the nineteenth century, opposing the Flemish made it possible to become a bit more British.

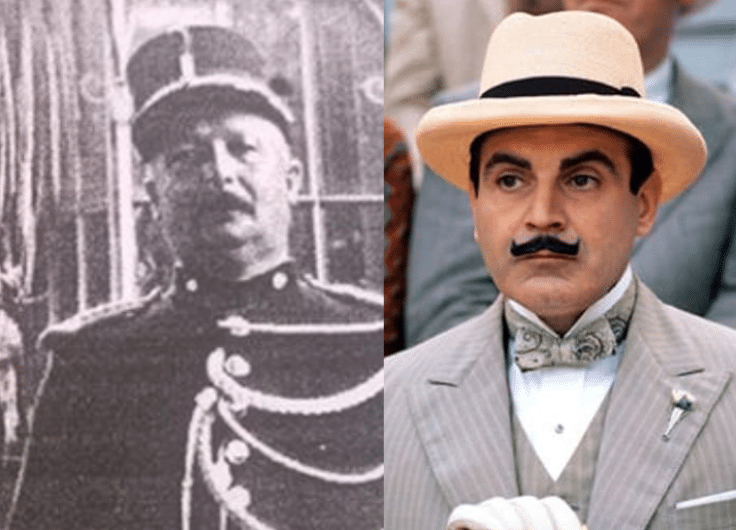

When Agatha Christie conceived the famous literary character Hercule Poirot, she had a very specific man in mind: Jacques Joseph Hamoir, a former Belgian gendarme who, after being wounded in the fight against the German occupier, had fled to England in January 1915. Christie met Hamoir in her hometown of Torquay, where many refugees were taken in. At least, that’s the story the Daily Telegraph told in 2014. Whether this man is specifically involved seems somewhat doubtful.

Belgian policeman Jacques Joseph Hamoir and David Suchet as the fictional detective Hercule Poirot

Belgian policeman Jacques Joseph Hamoir and David Suchet as the fictional detective Hercule Poirot© Archives Herstal

What is clear, according to Christie herself, is that Hercule Poirot is based on a Belgian war refugee. She wanted to pit him against that great British detective, Sherlock Holmes, who was tall and slender, a little dishevelled, addicted to drugs, a honeybee and wildly eccentric. Poirot, conversely, had a short, tucked-in frame, a penchant for tidiness and an ovoid head that he always tilted a little while he fiddled with his moustache.

There has always been contact between the British and the inhabitants of the country on the other side of the North Sea

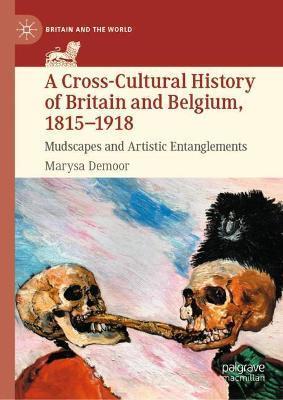

The subject of A Cross-Cultural History of Britain and Belgium, 1815 – 1918: Mudscapes and Artistic Entanglements by Marysa Demoor, a professor of English Literature and Culture at Ghent University, is that people build their own identities by defining themselves in relation to others. More specifically, Demoor explores how the British did exactly that by comparing themselves to the Belgians and reminds her readers that there had always been contact between the British and the inhabitants of the country on the other side of the North Sea, even long before 1815.

Matilda of Flanders, First Queen of England

Matilda of Flanders, First Queen of EnglandWilliam the Conqueror was married to Matilda of Bruges and a quarter of the army with which he invaded England in 1066 was composed of Flemings. Geoffrey Chaucer was also married to a Flemish woman, and in the Canterbury Tales, he describes how Flemish weavers who had emigrated to England were often made to feel ashamed.

But in 1815 something changed: the Battle of Waterloo took place, a seminal event in the development of British nationhood. Waterloo Station and Waterloo Bridge are so well established that we don’t even realise they were named after the battle that should in fact be called the Battle of Mont Saint Jean, because that’s where it actually took place. It was because the Duke of Wellington, who lead most of the troops, thought Waterloo sounded better and, as we know, history is written by the winners.

The Duke of Wellington leading the British troops at Waterloo, paiting by Robert Hillingford

The Duke of Wellington leading the British troops at Waterloo, paiting by Robert Hillingford© Wikimedia Commons

How much Waterloo fired the population’s imagination is apparent from the many paintings and poems devoted to it. A lot of blood was spilt there and drawn into the Belgian soil, which made it, somehow, a little bit of British soil, too. William Wordsworth thought it a shame that Wellington invariably walked away with all the credit, while the fallen soldiers and officers were hardly considered worth mentioning. Robert Southey, the poet laureate at the time, drew attention to the Dutch and Prussians who, like the British, had fought against Napoleon. Lord Byron felt the battle showed, above all, how the human condition centres on insurmountable death, and he lamented that it was essentially a defeat for freedom as the republic had lost to the kingdom. And then there was Walter Scott, who saw many similarities between the situation of the Flemish in Belgium and that of the Scots in the United Kingdom and thought it shameful that the battlefield was overrun with souvenir sellers just months after the battle. Indeed, Waterloo quickly became a place of pilgrimage for the British and perhaps they felt more British there than at home.

Walter Scott saw many similarities between the situation of the Flemish in Belgium and that of the Scots in the United Kingdom

Those pilgrimage journeys included visits to many cities, in fact, to a new country, Belgium. During their journeys to Waterloo, the place where the British nation took on a face, the travellers invariably also visited Ostend, Bruges and Ghent, and some even visited Antwerp. These stops also became decisive experiences for the formation of their identity; sometimes in a positive, but usually in a negative sense. By rebelling against the Flemish, it was possible to be a bit more British.

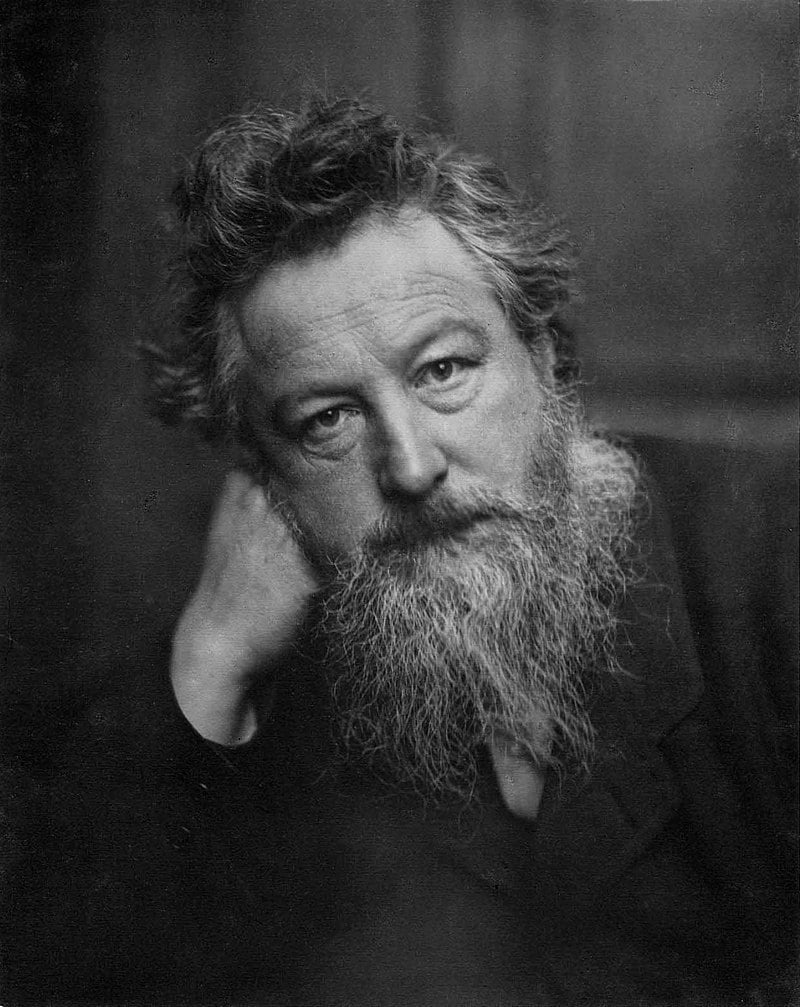

British designer, poet and artist, William Morris, loved Flanders.

British designer, poet and artist, William Morris, loved Flanders.© Wikimedia Commons

There were also exceptions. Frances Trollope, the mother of the writer Anthony Trollope, who had fled with her family to Bruges in 1834 because the creditors were getting too close, thought Flanders was beautiful. And she probably meant it, because she wasn’t in the habit of mincing words. For example, the book she wrote about Paris began with “What a dreadful smell.” William Morris, one of the men behind the Arts and Crafts movement, also loved Flanders. He went on a honeymoon there, understood Dutch and adapted two poems by Jacob van Maerlant into ‘Mine and Thine’, which appeared in his collection Poems by the Way (1891). From 1854 onwards he used Jan Van Eyck’s motto Als ich can, which essentially means ‘I have done this to the best of my ability’.

Most Britons who visited Flanders and Brussels mainly compared themselves very favourably to the Flemish

But most Britons who visited Flanders and Brussels mainly compared themselves very favourably to the Flemish, who were invariably considered stupid, vain and inferior; opinions, according to Demoor, that were also supported by Murray’s Guide to Belgium. The 1838 edition stated that one-third of Belgium was made up of French speakers and two-thirds of Dutch speakers. The 1860 edition noted that the Flemings were unfortunately deprived of the world language that was French and that this was clearly noticeable in their lack of development. That is why William Makepeace Thackeray (the author of Vanity Fair) was cheered up when the Antwerpers had difficulty speaking their French mother tongue, and why the British-naturalized American Henry James was disappointed that the Belgian refugees he received during WWI were imbecile Flemings, with whom he could do nothing because they were so slow-witted. No, he said to his friend Maurice Maeterlinck, who received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1911, the French speakers were really of a completely different intellectual calibre, forgetting for a moment that, though Maeterlinck wrote in French, he lived in the Flemish city of Ghent.

Rossetti’s painting, Girlhood of Mary Virgin, was an ode to the Ghent Altarpiece of the Van Eyck brothers.

Rossetti’s painting, Girlhood of Mary Virgin, was an ode to the Ghent Altarpiece of the Van Eyck brothers.© Wikimedia Commons

Waterloo faded into the background over time, as Demoor shows. William Morris ignored it and the Pre-Raphaelites did not pay it much mind, either. But the art of Van Eyck and Memling appealed to them all the more. In one of the best chapters of the book, Demoor takes a closer look at the influence that Jan and Hubert van Eyck’s The Ghent Altarpiece had on Dante Gabriel Rossetti during a visit to the city. Rossetti’s first oil painting, Girlhood of Mary Virgin, which he did upon his return to England, is in fact no more or less than an ode to the masterpiece in St Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent. While in Flanders, he also became acquainted with the idea of text on paintings and illuminated manuscripts and discovered that it is possible to make nudity acceptable to a large audience by placing it in a religious context. Rossetti’s Mary Magdalene, therefore, was allowed to be seductive. However, the British community, who still saw women according to a Victorian mindset, as either an angel or a whore, did not approve. So primitive and subversive, those Pre-Raphaelites who sought refuge in medieval barbarism.

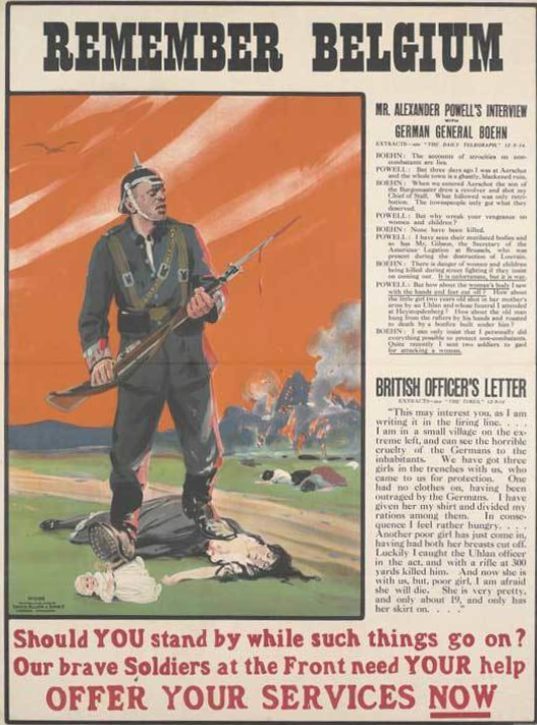

Remember Belgium, c.1914, poster by unknown artist and David Allen and Sons Ltd

Remember Belgium, c.1914, poster by unknown artist and David Allen and Sons Ltd© artuk.org

Demoor cannot hide that her book grew out of several previously published articles, which means that there is some repetition and, sometimes, half stories are picked up a hundred pages later, leading to a slight lack of cohesion. Still, her Cross-Cultural History of Britain and Belgium is particularly interesting. The way in which Demoor brings together death, mud and the birth of an identity is simply fascinating, especially when she talks about the second Waterloo, the Yser Front during WWI, when Flanders was seen as a raped or ravaged woman and Great Britain as the man who would defend her, making Mother Earth a source of macabre fertility. This is similar to Parade’s End, where Ford Madox Ford describes how a corpse is pulled from the ground in terms of a birth, as if the soldier doing the exhumation was a midwife. A photo in Demoor’s book shows a soldier’s grave made of a baby cot that can be seen in Nieuwpoort Churchyard.

One hundred and thirty-three British military cemeteries were established during and after World War I. Not only do they serve an emotional purpose, they are also official pieces of British territory that have made an immense contribution to the formation of British identity and, as Demoor writes, which will bind Flanders and Great Britain together forever and ever.

Marysa Demoor, A Cross-Cultural History of Britain and Belgium, 1815 – 1918: Mudscapes and Artistic Entanglements, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2022, 288 pp.