How Dutch Historians Unremembered Decolonization

Irish historian Paul Doolan claims that for many decades, Dutch historians have inadequately investigated the decolonization of Indonesia (1945-1949). In Collective Memory and the Dutch East Indies, the result of over ten years of work, he states that historians were not innocent bystanders. “They played a significant role in silencing and unremembering the experience of decolonization in Dutch collective memory.”

I recently visited the exhibition “Revolusi! Indonesia Independent” at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Browsing in the museum bookshop I noticed how, like all bookstores in the city, the main display contained numerous recent volumes about the Indonesian War of Independence (1945-1949). The following day I attended the online presentation in which over a dozen historians summarized the findings of their state-subsidized research into the role of Dutch military violence during the conflict. That evening I watched the news as prime minister Mark Rutte apologised to the people of Indonesia for the systemic violence of the Dutch military during the war. Later I heard historians explain their findings during television interviews. The next day I noted the prominence that national newspapers gave to the historian’s findings; history dominated the headlines, knocking the covid-19 pandemic and the imminent outbreak of war in Ukraine off the front page.

I valued how the exhibition included multiple perspectives and gave a voice to ordinary individuals who had experienced the events. I felt like a child in a sweet store when surrounded by all the new books. I admired the historians who remained dignified while navigating through the most uncomfortable historical event in the nation’s recent past. However, something seemed to be missing. The exhibition did not explain the decades long comparative silence of historians. I noticed the historians squirm uncomfortably when confronted with the obvious question: why has it taken so long?

This essay will provide the outline of an answer. I will firstly provide a summary of the Dutch historiography of decolonization. Then I will offer my explanation for the historiographical lacuna. I hope to persuade the reader that Dutch historians were not innocent bystanders. They played a significant role in silencing and unremembering the experience of decolonization.

Historiography

The Dutch centre of Indonesian studies was the University of Leiden, especially the Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (KITLV/Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). For decades, most of its esteemed faculty avoided the topic of the Indonesian War of Independence, which the Dutch referred to as the “Police Actions.” One exception was Cornelius Smit, who published a number of books on the conflict, though these focused almost exclusively on Dutch diplomatic decision making, all but erasing the fact that this had been a bloody, military conflict.

Artillerymen from the Dutch Marine Brigade fire high-explosive shells from a 25-pounder during an action in Tanjungsari, East Java, early 1947.

Artillerymen from the Dutch Marine Brigade fire high-explosive shells from a 25-pounder during an action in Tanjungsari, East Java, early 1947.Source: NIMH

The by now (in)famous television interview with veteran Joop Hueting on the VARA Achter het Nieuws programme in 1969, in which Hueting claimed that Dutch atrocities had been widespread, created a sudden interest in the issue of Dutch military violence during the war. The Dutch cabinet commissioned Leiden historian Cees Fasseur to oversee the writing of the Excessennota in 1969. Published a few months later, this superficial review of Dutch crimes concluded that the use of excessive violence had been incidental.

The government also commenced the publication of official documents relating to the decolonization conflict, under the editorship of S.L. van der Wal. In 1996 the 20th volume of Officiële Bescheiden betreffende de Nederlands-Indonesische Betrekkingen 1945-1950 appeared. This neutral style of publication ruffled few feathers. It had little impact on public perception of the war and some volumes were not even reviewed in the press. Historians quietly acquiesced in this act of collective unremembering.

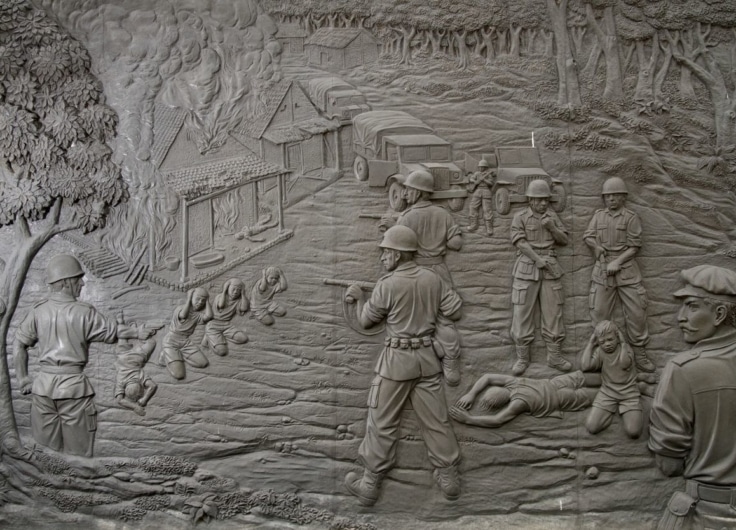

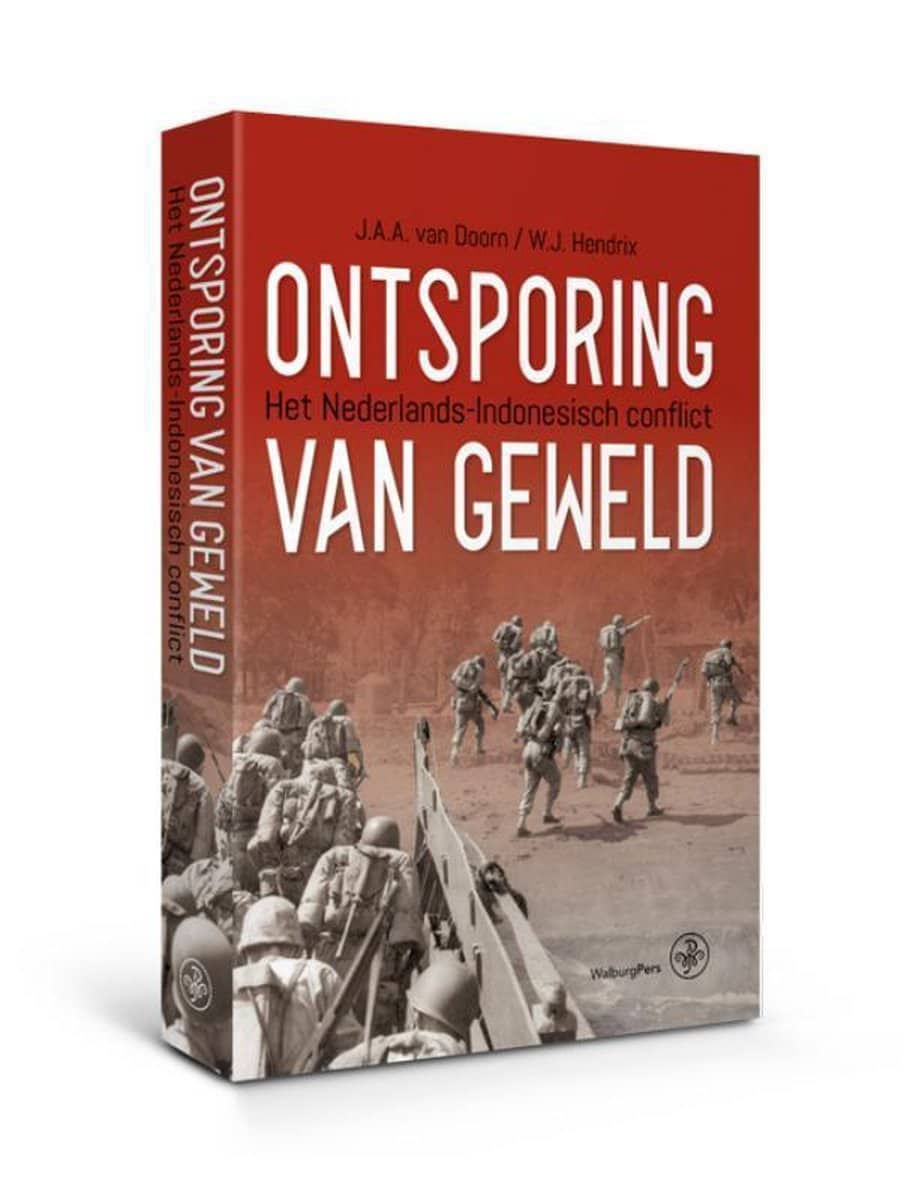

Ontsporing van geweld, was written in 1970 by two veterans of the conflict, J.A.A. van Doorn and W.J. Hendrix. It was the first independent attempt to analyse the Dutch use of excessive violence. As a work of history, it suffered from shortcomings; all case studies of excessive violence were anonymised and the scholars had not undertaken any archival research. Yet this first study remained the standard work for the next half a century.

In the mid-1980s, William IJzereff published a balanced review of Captain Westerling’s extra judicial mass killings on the island of Sulawesi. Loe de Jong, the most celebrated historian in the country, examined the years before decolonization in the former colony. His anti-colonial stance provoked a ferocious backlash, led by historians R.C. Kwantes and I. J. Brugmans. While writing the final volume of Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in the Tweede Wereld Oorlog, reports that De Jong would use the term “war crimes” led to further outrage and controversy.

The use of the term “war crimes” led to outrage and controversy

Excellent academic studies appeared during the late 1980s and 1990s from the likes of Jan Bank, Joop de Jong and Petra Groen. But these works shared a characteristic that sustained an unremembering of the war – the act of killing was, for the most part, absent from their pages. Even Groen, a military historian, avoided the act of mass killing by focusing on the logistics of war making. She studiously refused to use the term ‘war crimes” and even erased the term “war”!

Wim van den Doel of Leiden was not so shy. His Afscheid van Indië from 2000, was a pioneering, readable one volume history of the war in which he made some attempt to move beyond the traditional perspective. Stef Scagliola’s Last van de Oorlog (2002) analysed the difficulties that the Dutch had in coming to terms with this violent part of their history. Scagliola also co-authored, with Annegriet Wietsma, a work in 2013 that showed how the Dutch military left in its wake thousands of abandoned children and their Indonesian mothers. Around this time, thanks to the work of Indonesian activist Jeffrey Pondaag and the Committee of Dutch Debts of Honour, Dutch courts began writing the history of the war, finding the Dutch state guilty of war crimes in Indonesia. The publication of Remy Limpach’s De brandende kampongs van General Spoor in 2016 formed a turning point and led to the massive study that was presented to the public in February 2022.

Thanks to the work of Indonesian activist Jeffrey Pondaag and the Committee of Dutch Debts of Honour, Dutch courts began writing the history of the war, finding the Dutch state guilty of war crimes in Indonesia

Thus, Dutch historians had engaged with the subject for decades, yet their efforts focused upon certain aspects of the war while neglecting others. Few attempted to pen a total, multi-perspective history. Most historians unconsciously engaged in strategies of erasure, failing to construct sympathetic representations of decolonization that embraced the perspectives of ordinary agents – civilian victims of the war, conscripted Dutch soldiers, Indonesian republican activists (the work of Scagliola/Wiertsma formed a notable exception). Indeed the passions, reasons and motivations of Indonesian nationalists were silenced in works that were invariably based on official Dutch sources.

Indonesian nationalists ride through the streets with the ‘Boeng, Ajo Boeng’ poster, John Florea, Life, 12 November 1945. Unknown photographer. Unknown collection

Indonesian nationalists ride through the streets with the ‘Boeng, Ajo Boeng’ poster, John Florea, Life, 12 November 1945. Unknown photographer. Unknown collectionFragility of national identity

Now let me suggest an explanation for this state of affairs. To begin with, working through a violent historical reality perpetrated in the nation’s name frequently conflicts with the fragility of national identity. The conflict between the reality of the nation as the source of excessive violence and the self-perception of the nation as virtuous, was compounded in the case of the Netherlands, where the national collective shared a view of the nation as being not only virtuous, but also being an innocent victim. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s the Dutch cultivated a common perception of themselves as the innocent and virtuous victim of a terrible occupation by Nazi Germany (and the Japanese). The suffering of Dutch Jews was integrated into a larger, national suffering. The most famous victim of the Holocaust, Anne Frank, gradually became the iconic image of national innocence and virtue defiled. As the collective memory of German and Japanese occupation occluded the memory of decolonization, it would be cognitively difficult for the Dutch to sustain a view of themselves as victim, while recognizing that they were simultaneously the source of mass colonial violence. Historians who wished to correct this incomplete self-image, would invariably find themselves working against the grain. It would take courage. It turns out, such historians were rare.

© Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson Magnum Photos and ANP

Colonial links

During the colonization of Indonesia, Dutch historiography had been the handmaiden of imperial power. Future practitioners of the profession imbibed colonial ideology from the senior scholars. The peoples of the colony may some day be ready for independence, this was a view shared by ‘progressives,’ but that day lay in a distant future. There were exceptions to this paternalism. During the 1920s and 1930s, B.J.O. Schrieke and J.C. van Leur both developed approaches to Indonesian history that emphatically rejected Eurocentrism. G.J. Resink, who chose Indonesian nationality after 1949, developed these perspectives further. However, all three historians worked far from the academic centre of colonial history; they penned their best work from the periphery.

The academic heartland of colonial studies was centred in Leiden and Utrecht, where colonial officials had been educated and trained. To begin with, nearly all scholars who engaged with the history of decolonization had direct personal links with the former colony. Smit and Kwantes in Leiden, Brugmans in Amsterdam and Van der Wal in Utrecht had all held prominent official positions in the Dutch East Indies; Fasseur in Leiden was born in the colony. It is perhaps too much to expect that universities that prided themselves in running an empire from afar, could overnight be converted into centres of critical postcolonial excellence. Instead, the colonial history department in Leiden remained a bastion of old-fashioned thinking, where senior scholars emphasized traditional values, avoided novel approaches in historical studies, and introduced younger generations to the delights of Orientalist scholarship.

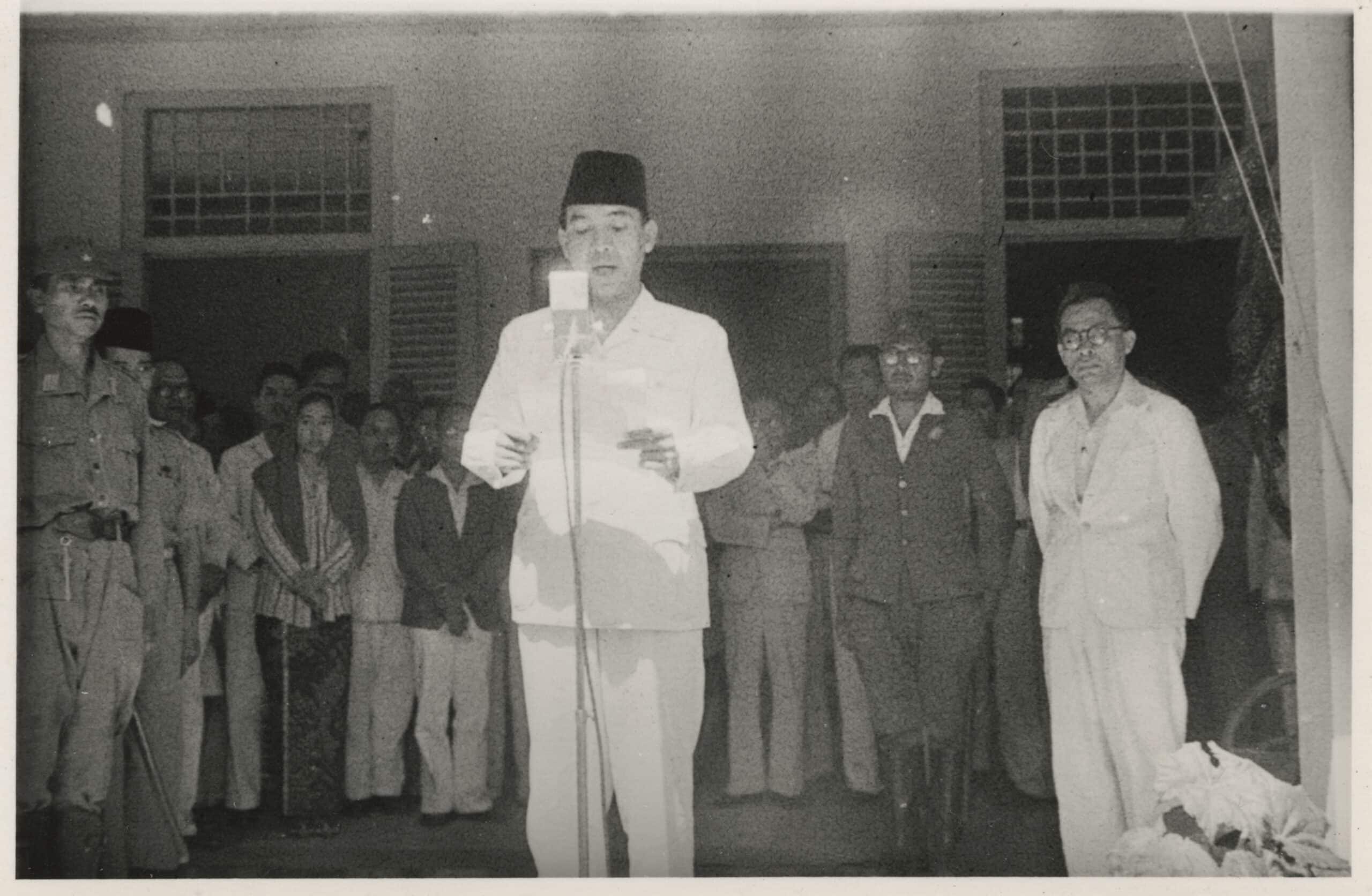

Sukarno, prominent leader of Indonesia's nationalist movement during the colonial period, proclaiming the independence of Indonesia from his house in Jakarta on 17 August 1945. Soemarto Frans Mendur (IPPHOS, Indonesia Press Photo Service). The Hague, The Netherlands Institute for Military History

Sukarno, prominent leader of Indonesia's nationalist movement during the colonial period, proclaiming the independence of Indonesia from his house in Jakarta on 17 August 1945. Soemarto Frans Mendur (IPPHOS, Indonesia Press Photo Service). The Hague, The Netherlands Institute for Military History© Antara/IPPHOS

The historical guild

The tight-knit circle of colonial historians formed a relatively small group that operated like a guild. It was helpful to young scholars if they had connections within the former colonial elite, graduated from the right secondary schools and were members of the right student association. Knowing the right people meant careers could be made with a tap on the shoulder. Members of the guild promoted one another’s scholarship, while keeping mavericks outside.

Members of the guild shared an insistence that doing proper history meant avoiding value judgments, never playing the role of judge and maintaining a strict neutrality. Good historians were professionals who did not allow passing fashions or innovations to sully their expertise. This meant avoiding anachronistic terms like ‘excessive violence,’ ‘war’ and ‘war crimes.’ Balance was a value highly favoured within the guild. Maintaining a balanced approach might result in eventually achieving a position of some eminence, like becoming an advisor to the government or royal family.

The field court martial of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army in Jakarta, 1949

The field court martial of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army in Jakarta, 1949Source: P. van Dael, NIMH, Dienst voor Legercontacten

Members of the historical guild fetishized pure research. Assembling collections of official (Dutch) primary documents was a skill more highly ranked then original insights or historical interpretation. Thus, guild members imbued a risk-averse attitude, avoided making sweeping statements, refrained from theoretical speculations and shunned controversial issues. There is more than a nugget of truth behind Rudy Kousbroek’s remark during the 1990s, that Dutch historians “express themselves when something is, not just historically, but politically no longer disputed.” Few had the courage to break ranks.

Not surprisingly, the more significant historical studies were created by academics on the periphery of the guild. Van Doorn and Hendrix were sociologists, not historians. IJzereef was a student at University of Groningen when he started his research; he never pursued an academic career. Loe de Jong was a specialist in World War Two, not in colonial history. Scagliola is the child of Italian immigrants and has spent much of her career in Luxembourg and Rotterdam, specialising in Digital Humanities. Limpach is Swiss-Dutch. His work first appeared in German as a dissertation at the University of Berne. The best single account of the Indonesian War of Independence to my mind is Revolusi: Indonesië en het ontstaan van de moderne wereld (2020), a multi-perspective combination of traditional and oral scholarship and a cracking good read. The author is David van Reybrouck, an independent scholar and a Belgian to boot.

Conclusion

Today there are dozens of excellent Dutch scholars producing stimulating, original works on the Indonesian War of Independence – too many to begin mentioning names. But why did it take so long? My conclusion, unpopular as it may be, is that historians need to stop blaming other groups such as politicians, military authorities, journalists, Indische or veteran groups. In a risk-averse academic culture, until recently few Dutch historians had the courage or imagination to break from the confining strictures of the guild.