How Missing Soldiers Regain Their Identity

The bodies of almost a hundred thousand soldiers who died in Belgium’s Westhoek region during the First World War have never been found. Their mortal remains still lie hidden in the Flemish clay. The exhibition Missing at the Front. Unearthing Names in the In Flanders Fields Museum shows how some of these missing soldiers have got their identity back thanks to archaeological and historical research.

The exhibition looks back on more than twenty years of archaeological research. Maps and aerial photographs provide an overview of the places where human remains were found, while Archaeological photos and a scale model show the condition in which they came to light a century after the war. In addition, a timeline, unique historical images and military maps and drawings take you back to the lines, the trenches and the bomb craters where the soldiers lost their lives.

Missing at the Front. Unearthing Names captures the human suffering caused by the war, with revealing figures and graphs, tangible personal objects and gripping archive documents. You can read letters from parents, desperately searching for their missing sons, and you stand face to face with the excavated possessions these soldiers had with them at the fatal moment. It is these personal objects that can often lead to the identification of a fallen soldier.

Scenography of the exhibition 'Missing at the Front' in the In Flanders Fields Museum

Scenography of the exhibition 'Missing at the Front' in the In Flanders Fields MuseumHistorical context

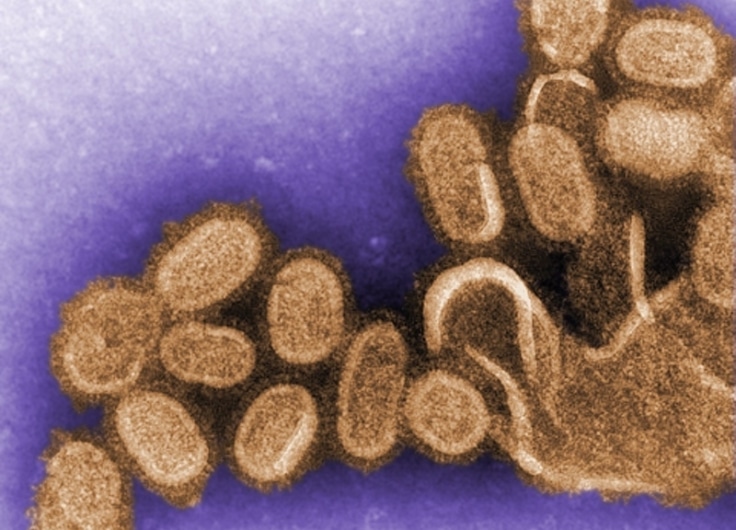

The First World War was the first war on an industrial scale – in almost every respect. The totality of the war, the new technologies and the massive deployment of people and equipment resulted in unprecedented devastation, in which millions of people and animals died and the landscape was destroyed. The scale was such that it left more than a physical scar along the whole front line. In the collective memory, there is a sense of a ‘lost generation’, due to the many victims the ‘Great War’ claimed from almost every nation.

The scale of the fighting and the huge impact of the artillery on the landscape meant that more soldiers than ever before went missing or have no known grave. Some were left behind on the battlefield where they died, their bodies were swallowed up by the mud or shot to pieces by the relentless artillery. Others were given a hasty burial on the battlefield by their comrades-in-arms, but any grave markers were destroyed, so that their graves were impossible to find after the war. Mine explosions or direct hits also caused some to go up in smoke.

The German, Lieutenant Engelberg, who experienced the horror of war during the Battle of Passchendaele (also known as the Third Battle of Ypres) in 1917, describes very movingly the fear that soldiers had of going missing: “The men no longer fear death, we have made peace with the idea of our own demise. A much heavier burden is the fear of being forgotten on foreign soil – an infamous end for any soldier. Swallowed by the earth, far from home, with no sign of remembrance, separated from your comrades and family in your homeland. Forgotten – no one wants such a fate (…)” — Lieutenant Engelberg, Pionier-Btl 13, Staden, 27 September 1917”. (Letter private collection, R. Schäfer)

After the war, the almost impossible task of clearing the battlefields and finding the dead began. Gu Xingqing – a worker in the Chinese Labour Corps, which was deployed for this purpose among others – described it very aptly in 1919: “The bodies of the English had to be dug up as well, in order to bury them. But the battlefield was vast. Recovering the dead was far from easy.” The bodily remains of ten thousand soldiers were recovered after the war, but could not be identified, so they were buried beneath an anonymous tombstone.

Fallen soldiers left behind on the battlefield, collection In Flanders Fields Museum

Fallen soldiers left behind on the battlefield, collection In Flanders Fields Museum© In Flanders Fields Museum

In Belgium, the names of nearly 103,000 missing Commonwealth soldiers are engraved on one of the monuments to the missing, such as the Menin Gate. Of these, 47,500 are buried under an anonymous gravestone. A cynical calculation makes it clear that the bodies of around 55,500 dead were left on the battlefields. The figures are more difficult to establish on the German, French and Belgian sides, but tens of thousands of them are missing, too.

Excavations

Every year, the remains of missing soldiers are found during archaeological excavations or by chance during works. The police are always notified, in order to exclude criminal offences. Then, if it is clear that the remains are archaeological, a physical anthropologist assists archaeologists to carefully unearth the bones and other items. Every minute detail counts and is recorded in drawings and photos. The context, location of the finds and study of the objects help to determine the nationality of the fallen and allow archaeologists to understand their fate. Every effort is made to make identification possible. After completion of the archaeological research, the remains and their possessions are handed over to the burial services of the countries concerned. Extraordinarily, all the bodies are reburied in a military cemetery with military honours. This is not the case in any other archaeological discipline.

Unearthing of a fallen soldier found by chance by a metal detectorist

Unearthing of a fallen soldier found by chance by a metal detectorist© Raph De Brant

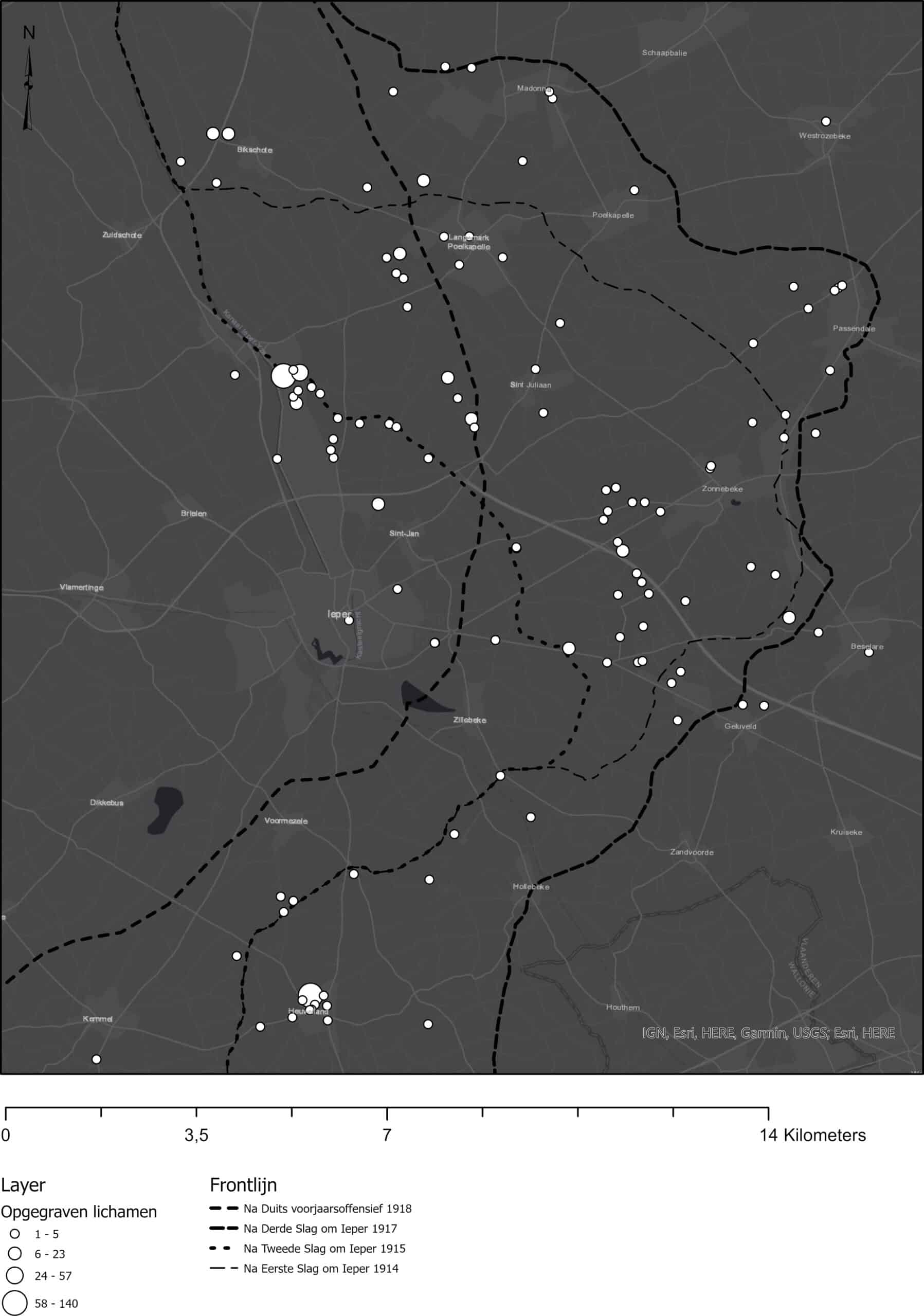

Since 1998, the remains of 728 missing war victims have been found. They are soldiers from all over the world, who fought under the British, French, German or Belgian flag. The majority of them were found in the Ypres Salient, the front line that curved around the town of Ypres. A distribution map of the finds gives a vivid picture of the battlefields and the places where the bodies were excavated. More than historical reality, this map mainly shows where large-scale infrastructure works have taken place or where excavations have led to large concentrations of finds. Places that stand out are the industrial areas near Boezinge – where amateur archaeologists first brought this problem to light – and the crowdfunding excavation ‘Dig Hill 80’, where archaeologists uncovering a German bulwark in Wijtschate found 110 dead in barely a hectare of land.

Excavations reveal a wide range of ways in which bodies were buried and burial sites came into existence, as well as why so many missing persons are still uncovered every year. What archaeologists find also varies greatly.

Some soldiers were once buried, but their graves were later lost. These were usually rather decent burials, with bodies in coffins or more provisionally wrapped in a piece of canvas or a rain cape. In as far as it was possible, they were generally laid out rather neatly too, with their arms crossed on their chests, for example. During such burials, in individual or collective graves, the soldiers were normally stripped of personal objects and other evidence of identity. These items were taken and sent back to the home front or had to be handed over to the military administration. Such graves, sometimes in real burial pits or existing dugouts or bomb craters, were often marked, but the markings and other orientation points in the landscape were frequently lost, so that the graves that were discovered by archaeologists could no longer be found after the war.

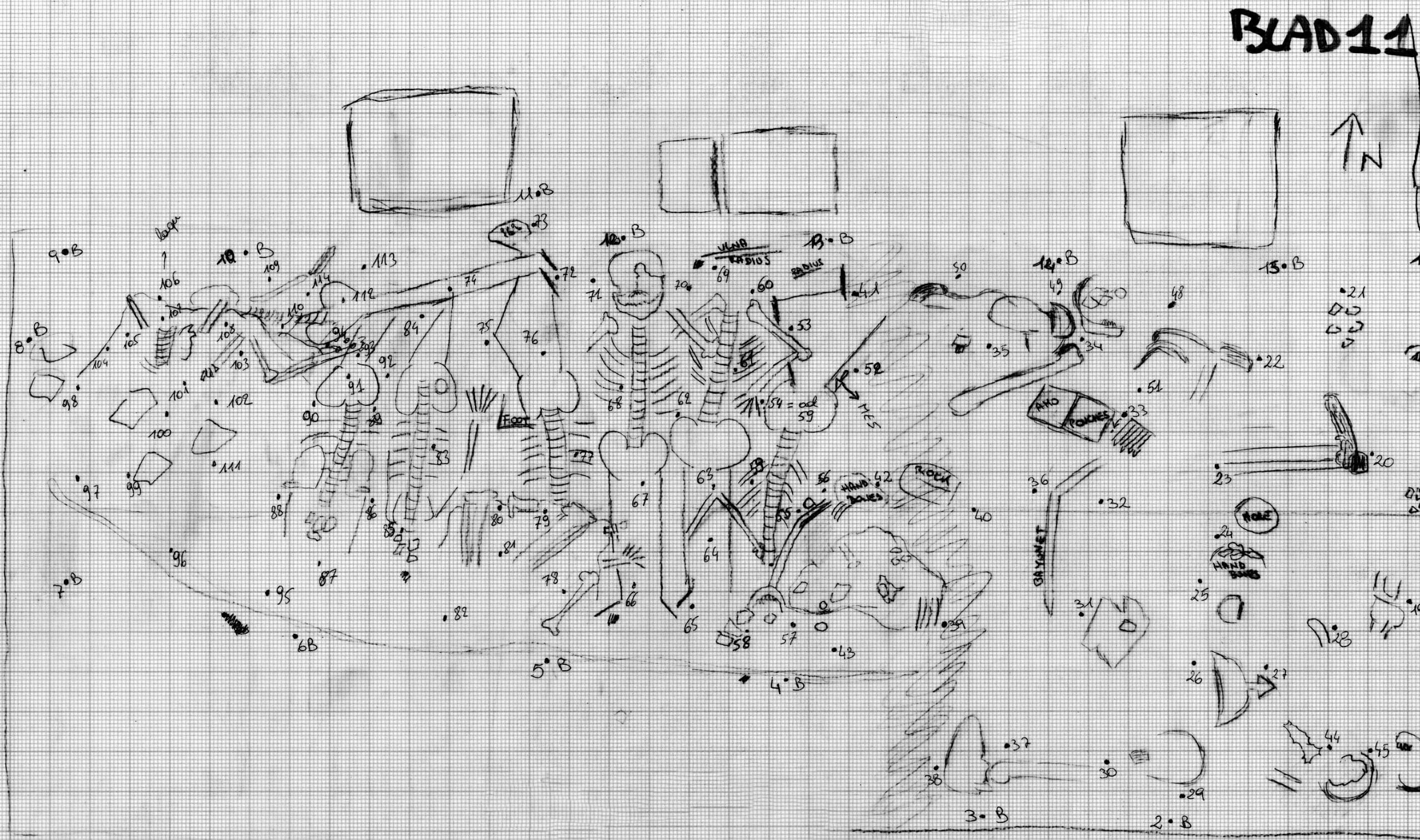

Situation sketch of a German mass grave near Wijtschate

Situation sketch of a German mass grave near WijtschateHowever, the majority of the missing were never ‘buried’ in the ritual sense of the word and disappeared in all manner of ways amidst the violence of war. They ended up in bomb craters, trenches, foxholes, tunnels, streams, ponds and any possible type of cavity and were accidentally or deliberately buried under the soil without any form of ritual. Even the bodies that initially remained on the surface were, in one way or another, buried, covered over or destroyed. Some were nonetheless recovered and buried in a real grave or collected in a charnel pit, still, others were buried, deliberately or otherwise, and found in the position in which they died or were left. They are often found in full regalia, with their uniform, equipment and weapons, but also with personal belongings – photos, postcards, souvenirs and so on.

Not all missing soldiers can be recovered. Because of the completely annihilating artillery fire in some zones, bodies and their graves were also destroyed and, although tiny fragments are still sometimes found, only their human origin can be established. Other bodies lie sprawled in heaps or are partly destroyed, so that only a limb or half a body is recovered. The ravages of time, too, are merciless, so that after more than a hundred years under the earth, depending on the type of soil, some remains have already largely decomposed.

Another contributing factor is the subsequent destruction of the remains by earth-moving activities such as construction, road building, agriculture and the laying of utilities. These are not always subject to archaeological regulations, but any discovery of bodies is supposed to be reported to the police. With few exceptions, however, there are no such reports – a statistical impossibility. This is not always deliberate, sometimes the remains are unwittingly destroyed by ever-deeper ploughing.

Distribution map showing bodies excavated in the Westhoek

Distribution map showing bodies excavated in the WesthoekIdentification

Identifying human remains is often difficult. Nonetheless, 43 of the more than 700 bodies that have been unearthed in the past twenty years have been given a name again. Identification is only possible thanks to meticulous excavation work. Mostly, identity tags or objects bearing initials or other personal details provide the decisive answer. Often additional historical or biological research is required. In all cases, identification is only final and conclusive after comparison with the DNA of relatives. Identifying missing persons is not only interesting for science; relatives get more clarity about what happened to their ancestor, whom they can finally lay to rest in a dignified grave.

Personal story of Private John Lambert

In the early morning of 16 August 1917, the Medical Officer of the 2nd Royal Hampshire Regiment sent a message to the officer responsible for organising the evacuation of the wounded. The stretcher-bearers of the field ambulance that had to pick up the wounded from his regimental aid post near Taffs Farm (Melkerijstraat, Langemark) had not turned up, and the medical post was gradually filling up. While he waited for an answer, he took the initiative of calling in German prisoners to bring back the first wounded soldiers. Nevertheless, it took until the afternoon before everything got back to normal. Although extra stretcher-bearers were sent out to the medical posts near the farm, it was after 4 pm before most of the wounded had been taken away – a real tour de force, as this sector was under intensive artillery fire the whole time.

Private John Lambert

Private John LambertA few hours earlier – at 5.45 to be precise – French and British units had gone on the offensive again in the second phase of the Battle of Passchendaele. The 29th Division of the British Army was on the west bank of the Steenbeek opposite Langemark, roughly between the Bikschotestraat in the north and the old railway in the south. Their objective was to take the northern edge of the village and advance to the banks of the Broenbeek on the other side. The 88th Brigade was allocated the southern sector, with the 2nd Royal Hampshire Regiment on the right flank and the 1st Royal Newfoundland Regiment on their left. For the Newfoundlanders, the attack went relatively smoothly. They achieved their objectives without too many losses. To their right, however, the Hampshires had more difficulty. The 20th

Division – which was on their right flank – had been delayed, leaving that flank unprotected, so that they had to contend with machine-gun fire, which made a lot of victims.

In the spring of 2016 – just under 99 years later – a new natural gas pipeline was planned between Langemark and Ypres. Its route ran from the Melkerijstraat more or less parallel to the Steenbeek, along the front line of the 29th

Division in fact. A branch was planned at the level of the dairy producer Milcobel, to directly supply the factory site. Prior to the construction of the pipeline, a large-scale archaeological survey was carried out. In April 2016 the team came across the human remains of several soldiers, who appeared to have been buried behind a line of dugouts, just north of Taffs Farm.

This line of dugouts is mentioned in the reports of the medical units of the 29th Division. On the one hand, it was a relay post for the field ambulances, but it was also used as the forward advanced dressing station. As a result, many wounded were gathered here and around the regimental aid post of the 2nd Hampshires, which was also located close to Taffs Farm. As it took some time for the evacuation to get underway, it is not unlikely that some seriously wounded soldiers died there and were possibly buried in temporary field graves. Everything seems to indicate that it was this forgotten burial ground that the archaeological team had found.

In the final months of the war, the banks of the Steenbeek were repeatedly targeted by artillery, so that every trace of the location of the field graves was erased. Almost literally, unfortunately. In total, the mortal remains of eight soldiers were salvaged. However, the bodies that were found had been completely mixed up by the many explosions and could no longer be distinguished from each other. Nonetheless, based on the insignia found, it was possible to determine which units the dead soldiers had served in – units of the 29th Division, obviously: the Royal Hampshire Regiment (2x), the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, the Royal Fusiliers and the Gloucestershire Regiment. There was also one German soldier and one undetermined.

Initially, there was little hope of identifying the soldiers. But keen detective work by the Canadian authorities has now finally produced results. DNA research yielded a match that gave at least one of the eight a name again, Private John Lambert. His personal file indicates that he died of his wounds and was buried near Ruisseau Farm, so presumably, he was brought, seriously injured, to the forward advanced dressing station and succumbed to his wounds there.

He was only officially declared dead on 20 September 1917. As a result, John’s parents first received a letter at the end of August, announcing that he had been wounded. On 3 October 1917, a telegram followed with news of their son’s ultimate fate. John Lambert was only 17 years old. Almost exactly 1 year earlier, as a 16-year-old, he had lied about his age and enlisted in the Royal Newfoundland Regiment. On 7 June 1917, he joined the battalion on the battlefield, a mere two months before the attack that cost him his life.

John Lambert will be buried, with those who shared his fate, at New Irish Farm Cemetery.

Missing at the Front. Unearthing Names, until 31 May 2022, In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres.