How Much Colour Can The Flemish Art World Tolerate?

Superdiversity and interculturality have long ceased to be societal choices and become inevitable facts. Meanwhile, a particularly articulate generation has grown up with diverse, mainly North African, backgrounds. They are demanding their place and will no longer put up with others speaking on their behalf. How is the debate conducted in the Flemish cultural sector, and in particular in the performing arts?

In March 2019 Antwerp officially became a superdiverse city: the majority of the population has a migrant background. World cities such as New York, São Paulo, Toronto, Sydney and London have been majority-minority cities for some time, with the majority of residents consisting of a wide range of minorities. In the twenty-first century the phenomenon has also arisen in Belgium and the Netherlands. In Brussels, Genk, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, The Hague and now also Antwerp, residents from Belgian or Dutch backgrounds make up less than half the total population. Antwerp now has more than 170 different nationalities.

Cities have effectively become “the world’s contact zones”: zones where cultures and people previously separated by geography, history, race, religion, ethnicity et cetera are “compelled” to deal with one another in the same space, to negotiate, and to do so in a context of unequal power relationships and a permanent experience of being lost in translation.

The idea that Flemish performing arts are too white has been a sore point and even a reproach in recent years

It’s no wonder that new social sensitivities come into conflict with existing behavioural patterns and cultural traditions. The discussions about Zwarte Piet and Tintin in the Congo are good examples: one group’s ancient custom or innocent entertainment is perceived as offensive and insulting by another because it invokes a traumatic history of oppression and racism. The collective Mémoire Coloniale et Lutte contre les Discriminations, for example, reacts very critically in a press release to the digital edition of Hergé’s book: “This cartoon feeds the perception that Africans are sub-humans (…). The book contributes to contempt for and dehumanisation of Africa, Africans and Congolese people in particular.”

An example of a different order is a ban on advertising lingerie in the district of the Hasidic community in Antwerp. Discussions on the right of colonial monuments to exist and on certain street names are also part of this. As diversity grows, ethnic, cultural, religious and other such identities are more sharply defined and turned into social claims. The more influential and publically articulate certain groups become, the more they make their mark on the political and social agenda. That is an irreversible and democratic process. How is this discussion conducted in the cultural sector and specifically in the performing arts?

A sea of white people

Tunde Adefioye

Tunde Adefioye© Hugo Lefèvre

The idea that Flemish performing arts are too white has been a sore point and even a reproach in recent years. In his opinion piece ‘Een zee van witte mensen’ (‘A sea of white people’, De Standaard,

5 August 2017) Tunde Adefioye, city dramaturge of the Brussels KVS, introduced a new, fierce tone to the debate. The Theater aan Zee festival, which takes place in summer in Oostende, focused almost exclusively on white audiences and certain performances were even insulting to audience members of different skin colours, the city dramaturge argued. His comments caused considerable commotion.

Rachida Lamrabet

Rachida Lamrabet© Koen Broos

A few months earlier the discussion about inclusion and exclusion had already been brought into focus as a result of the controversial firing of writer and jurist Rachida Lamrabet by the Centre for Equal Opportunities for speaking out several times against the burka ban. In response Lamrabet wrote the book Zwijg, allochtoon! (‘Silence, immigrant’, Epo, 2017).

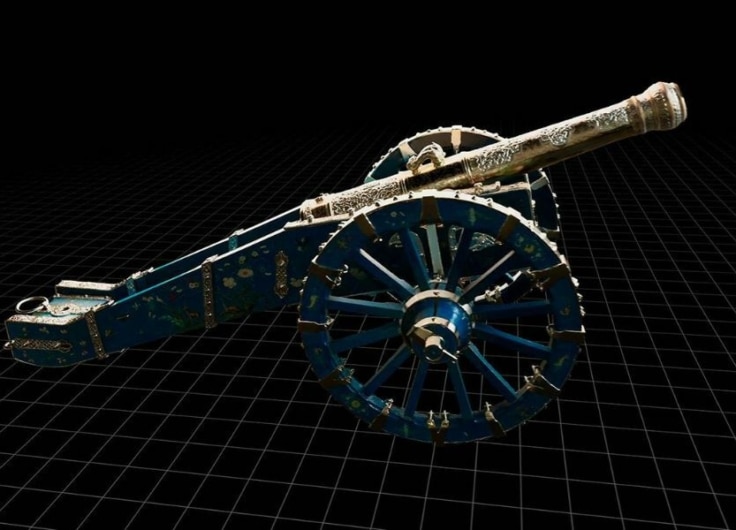

The debate culminated in reactions to the revival of the Hugo Claus play The Life and Works of Leopold II by the Brussels KVS, directed by Raven Ruëll. People complained that the play represented Africans in a clichéd and even humiliating manner. The voices claiming that Flemish theatre is too white, both on stage and behind the scenes, sound ever louder. It’s not just the theatre itself either: drama courses also lack colour, as do the audiences, and the repertoire performed…

The Life and Works of Leopold II by the Brussels KVS

The Life and Works of Leopold II by the Brussels KVS© KVS

The public debate on diversity has been in progress in Flanders for at least twenty-five years. Black Sunday, the infamous breakthrough of the extreme right-wing movement Vlaams Blok (now Vlaams Belang), with its racist, anti-migration programme in the Belgian parliamentary elections in 1991, was a wake-up call. It led to a plethora of multicultural and intercultural initiatives in the 1990s, which affected the cultural and artistic sector too.

Between 2004 and 2009 the Flemish minister for culture at the time, Bert Anciaux, placed great emphasis on diversity and interculturality in his policy. Since then “participation” and “diversity” have become important categories for policy and consequently also for subsidies. But all that has had little effect on the ground. Theatre in particular remains untouched. Organisations, companies, ensembles, repertoires, courses and audiences have barely diversified in the past two decades, if at all.

Malcolm X

That Flanders is behind the times is unfortunately all too true. There are several reasons for this. Awareness of Belgium’s history as a colonial power is almost completely absent, so there has been no serious start on dealing with the colonial past or building a new relationship with Congo. For decades community disputes have eclipsed the fact that Belgium’s future long ceased to be determined by two language groups and instead is affected by a patchwork of communities.

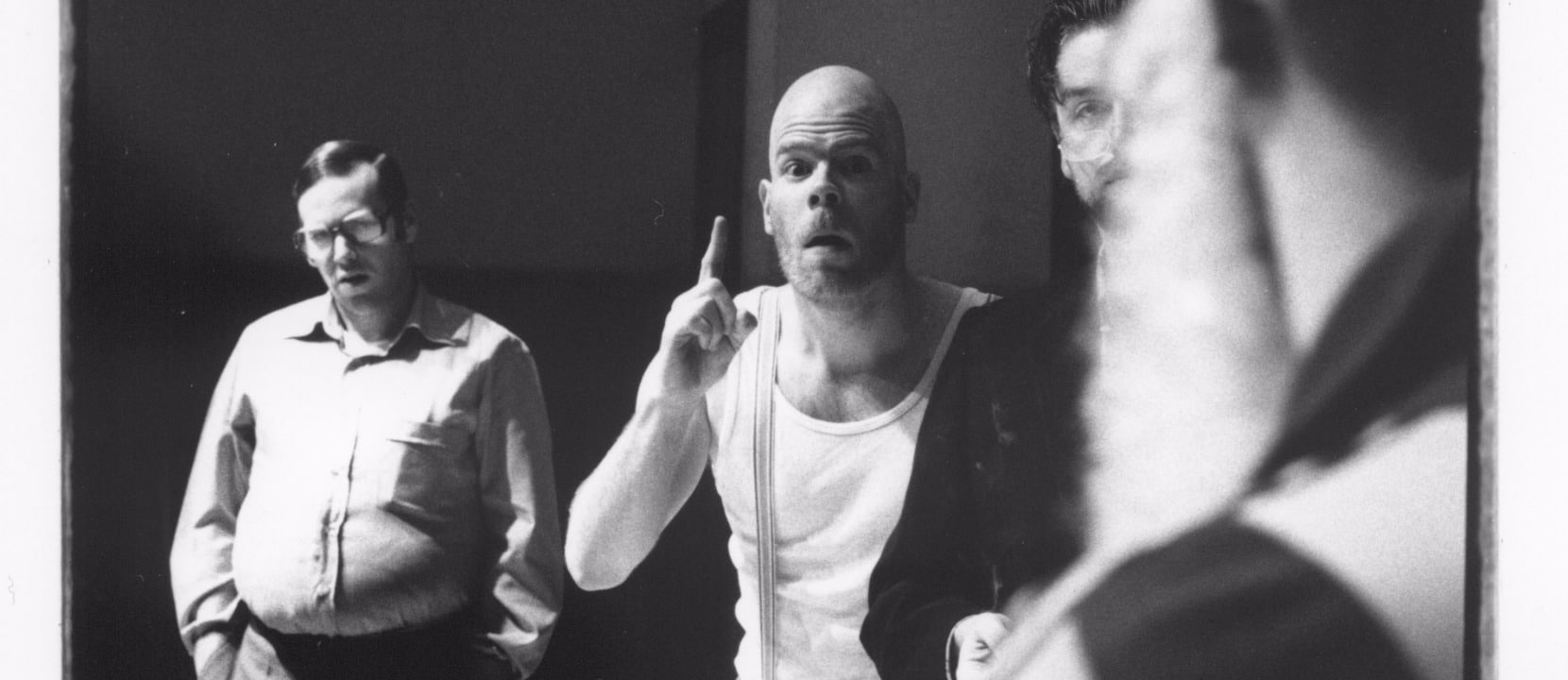

The intensity with which this discussion is conducted at present has a lot to do with that historical slowness. The big difference from the debate of, say, ten years ago is that now a very articulate generation with diverse backgrounds (mainly from North Africa or elsewhere in Africa) has grown up; they are demanding their place and no longer put up with others speaking on their behalf. It is probably no coincidence that at the KVS in 2017 a performance was created based on the character of Malcolm X.

It was a collaboration between artists from Brussels, Antwerp, Amsterdam and London. In urban art forms such as slam poetry and hip-hop, Malcolm X’s fight was translated to today’s city. Malcolm X was a 1960s radical separatist who produced intelligent and prolific criticism of white America. In the theatre concert, his legacy was weighed up against the challenges of our time.

Malcolm X by KVS

Malcolm X by KVS© KVS / Danny Willems

A new generation of critics, mainly grouped around the magazines Etcetera and rekto:verso, have made diversity one of their main raisons d’être. While the debate was mainly conducted among white voices until five years ago, that is no longer the case. Now we are beginning to hear the voices of a group of people who have experienced exclusion at first hand. That changes the tone and the slant of the discussion. The editors of rekto:verso wrote this in their themed issue on decolonisation:

What white people call ‘diversity’ or ‘interculturalisation’, to people of other skin colours is anything but a matter of time, artistic hype, a subsidy tick box. It’s about a form of violence and racism experienced on a daily basis, a structurally ingrained inequality in power, resources, voice, recognition, visibility, and image. From that perspective, ‘diversity’ is not simply a ‘topical issue’, but part of a much longer history of domination: a conscious or unconscious perpetuation of colonial patterns in which the master sees himself as the norm.

They do not beat about the bush in the terms they use: the “white system” is described as violent, racist, normative and the legacy of a long colonial history.

White privilege

This last remark touches on the core of the issue. The discussion is primarily about the recognition of a different, excluded and until now barely heard history. For instance, since 2018 Flanders too has organised a Black History Month. It’s a tradition from the United States in which for a month special attention is paid to black history and black role models. The Facebook page of Flemish Black History Month describes its importance:

Liberation is impossible until we redefine ourselves. Without a change in our own vision, we remain slaves to the ideas and values of the oppressor. Ideals and values which in the end attack the core of our existence. We must therefore see the world in terms of our own reality and discover who we really are. (…) Art gives us a brief glimpse of what more is possible. It is a way of dealing with the trauma caused by systems of oppression and a way of strengthening the voices that have been silenced.

Again, hard binary terms (“slaves” contrasted with “oppressors”) are used to describe the social tensions.

Here it is clear that a generation is speaking to demand its own voice and its own history. The identity discourse of authenticity (“seeing the world in terms of our own reality”, “discovering who we really are”) is not unproblematic, but the aspiration is clear: those silenced must now speak out and be given the chance to tell their story.

The discourse of this generation of young people points explicitly to (mainly African-American) post-colonial theory and is well constructed, but also militant and activist and therefore at times polarising. Intercultural relations are almost exclusively analysed in terms of institutionalisation, exclusion, appropriation, neo-colonialism and “white dominance”.

“White privilege is ever more emphatically identified as a core problem. For many people that takes some getting used to. White people are not at all accustomed to having a mirror held up to them,” claims the previously quoted editorial from rekto:verso. The use of the Dutch word “wit” instead of “blank” for “white” has set a good deal of ink flowing. “Blank” is considered a term with positive connotations, whereas “wit” indicates that a particular stance has been taken. “Blank” in some sense implies a promise of something universal, whereas ‘wit’ is placed in the middle of a range of positions.

Situated knowledge

That concept of white positioning is essential for starting an equal intercultural dialogue. Media scientist Ginette Verstraete speaks of “situated knowledge” in this connection. That is, “knowledge that takes responsibility for its many limitations and thus creates space for other visions, other possibilities, other ways of living together which do not necessarily profit one’s own people but also make space for others. And those others are not only women and the economically disadvantaged of one’s own country, but in this period of globalisation also men and women who come from elsewhere.”

Europe, the West, should, in other words, distance itself from its universalist and normative pretentions, it should be “situated”, recognise its limitations and on that basis enter into dialogue with other visions, from inside and outside. That realisation that the white perspective is “situated” and thus “limited” should gradually penetrate all levels.

The concept of white positioning is essential for starting an equal intercultural dialogue

“Situated knowledge” is not primarily about new content but a new attitude. It’s not a database of addresses and information relating to other cultures. It is first and foremost a new awareness. It is not so much a position as a disposition. It is not a solution, but the willingness to join with others in looking for answers to possible questions. The notion of “joining with others” is essential. Taking up a position has to do with expressing a clear opinion, with a specific statement. Taking up a position has to do with speaking.

Disposition has more to do with listening, with a willingness to listen. According to philosopher Benjamin Barber it is listening itself that forms the foundation of every properly functioning democracy: “We all think that democracy has to do with speaking clearly, speaking well…, but real democracy in fact is not about speaking, but about listening properly, hearing, empathy, about understanding the other, about seeing other people’s interests and finding common ground among them.”

Decolonise!

It is clear that the debate has moved on from adding colour to an organisation or administrative board. The point of the discussion is not just access to the system, but also change to that system whose institutions, courses, canon, quality criteria and judgements or prejudices are defined as dominant and white. From that perspective, the term “diversity” is increasingly replaced by the more direct and compelling demand “decolonise”. That is a reference to the essay Decolonising the Mind

(1986) by Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. Colonisation and decolonisation are often wrongly seen as peripheral phenomena, processes on the edge of the development of modernity and capitalism, when in fact they belong to its core: “Diversity without awareness of decolonisation threatens to become just another flavour of the month,” says Sruti Bala, assistant professor of theatre and performance studies at the University of Amsterdam.

Tunde Adefioye has drawn up a ten-step plan for the arts. It is meant as a guide for the sector to come to a more honest reflection of diversity in society. These are the ten steps he proposes:

1. Ask yourself how you can decolonise your institution.

2. If you’re a white cis male in your sixties, make a start on your exit plan.

3. Redistribute the resources between big players and small fish.

4. Allow your white institution to be taken over.

5. Open the canon.

6. Stop navel-gazing.

7. Avoid stealing the property of others.

8. Hack your code of quality.

9. Work towards transnational alliances.

10. Make your work floor a safe space.

This summary gives a good idea of the challenges that cultural institutions face. They must explicitly acknowledge their “white character” and in doing so “decolonise”. Meanwhile, Kunstenpunt (the support centre of the Flemish government for the development of visual arts, music and performing arts in Flanders and Brussels) provides a professionally supervised decolonisation pathway for organisations who want it. The code word is “breaking open”: quality, infrastructure, financial resources, staff composition, communication, the canon…

The point of the discussion is not just access to the system, but also change to that system

All that makes it clear that there are great and far-reaching challenges for white cultural institutions in Flanders. Superdiversity and interculturality have long ceased to be social choices and become hard, irreversible facts. The white cultural sector will be ever more sharply confronted with demands of culture and identity from minorities who no longer accept white hegemony and no longer wish to act as second-class citizens. The only thing that really helps is achieving more meetings, exchanges, collaboration, performances, debate and experience. Change takes place faster when people are not just confronted with ideas. In that respect, at this point there is a momentum that should be grasped, despite and thanks to the intensity of the current debate.

Edward Saïd, who more than others has emphasised the need for intellectual and cultural dialogue with the Orient, concludes his essay ‘Cultuur, identiteit en geschiedenis’ (‘Culture, identity and history’) with the following appeal:

Recognise the historical truth of your experiences; recognise the truth of other cultures and experiences, the majesty and manipulations of which culture is capable; recognise that culture is not a series of monuments but a ceaseless engagement with processes of aesthetic and intellectual expression and realisation; and, in the end, recognise in culture the potential for bold imagination and courageous statements. All the rest is less interesting.