How the Story of an Enslaved Boy Transformed Into a Shared Dutch History

The most detailed account of the life and the conditions of the plantation colony of Suriname at the end of the 18th century is recorded in English by the Dutch-Scottish army officer John Gabriel Stedman. It is through his writing that author-researcher Ineke Mok found Quaco, an enslaved boy captured on the coast of Ghana and transported to Suriname on one of the many slave ships. Mok reconstructed Quaco’s life story for the graphic novel Quaco: My Life in Slavery, which is now available in English complete with extensive teaching materials. But what does Stedman actually say about Quaco and how does he present his ‘futuboi’ to the reader?

In this article, I will trace and unpick Stedman’s descriptions of Quaco and argue that Stedman may give Quaco a voice in his diary, but that he too commits an act of ‘literary colonialism’ when he sacrifices Quaco’s individuality to adhere to 18th-century literary conventions. In addition, I will show that Stedman with his mixed heritage and his opportunistic stance is an exemplar of how transatlantic slavery was in practice a transnational affair. Quaco’s story puts the history of slavery in the Dutch colonies into a multilingual and transatlantic perspective, transforming Quaco’s “Miself Alone Excepted” into a shared history.

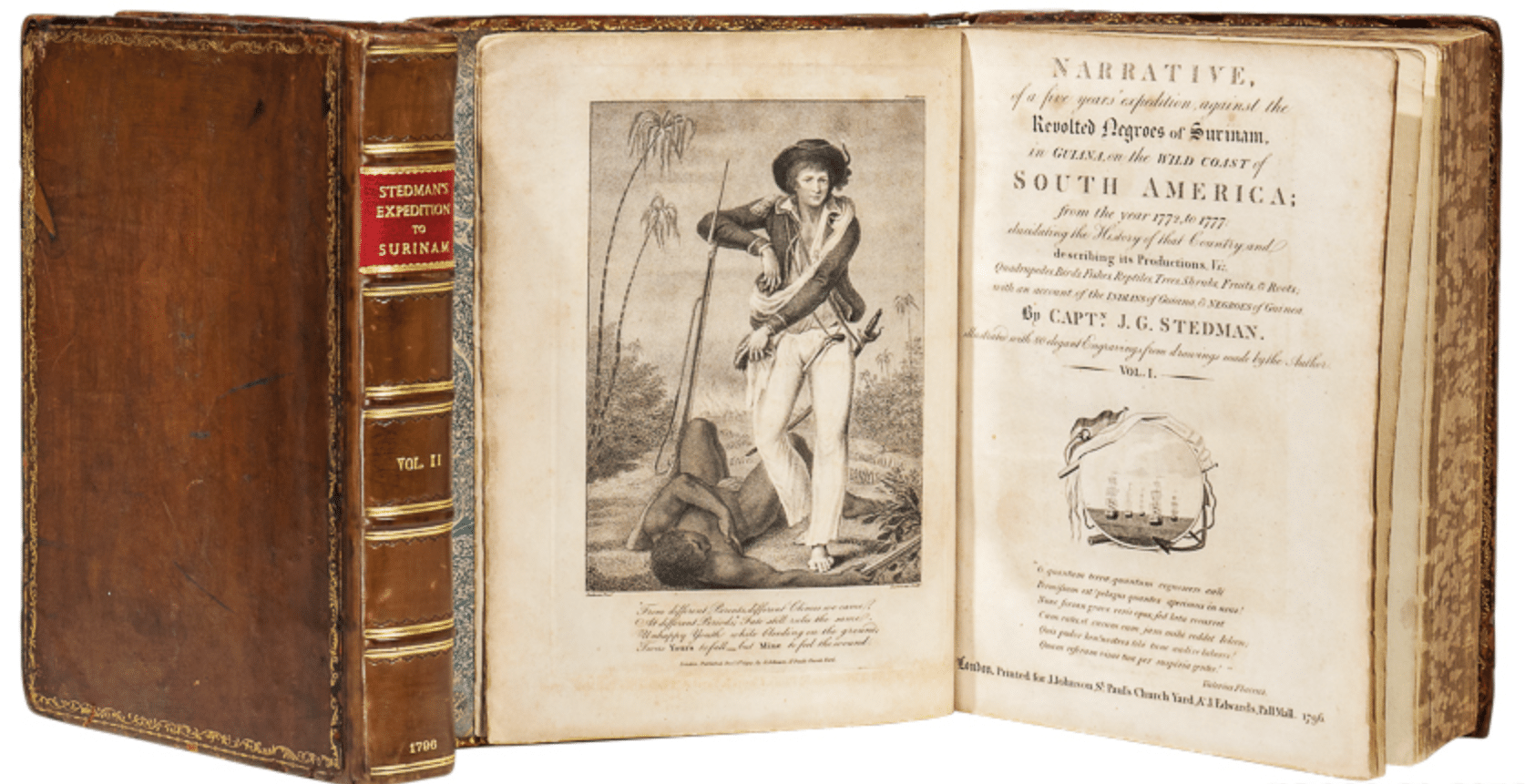

'Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam', written by John Gabriel Stedman, 1796

'Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam', written by John Gabriel Stedman, 1796© Bonhams Skinner

Quaco’s story occurs fairly late on in John Gabriel Stedman’s, Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (1790; 1796). (1) This encyclopaedic narrative is typical of 18th-century travel literature, of exploring new autobiographical and narrative modes, and offers a real-time view of life in Suriname. (2) It is the most comprehensive description of the Dutch plantation economy.

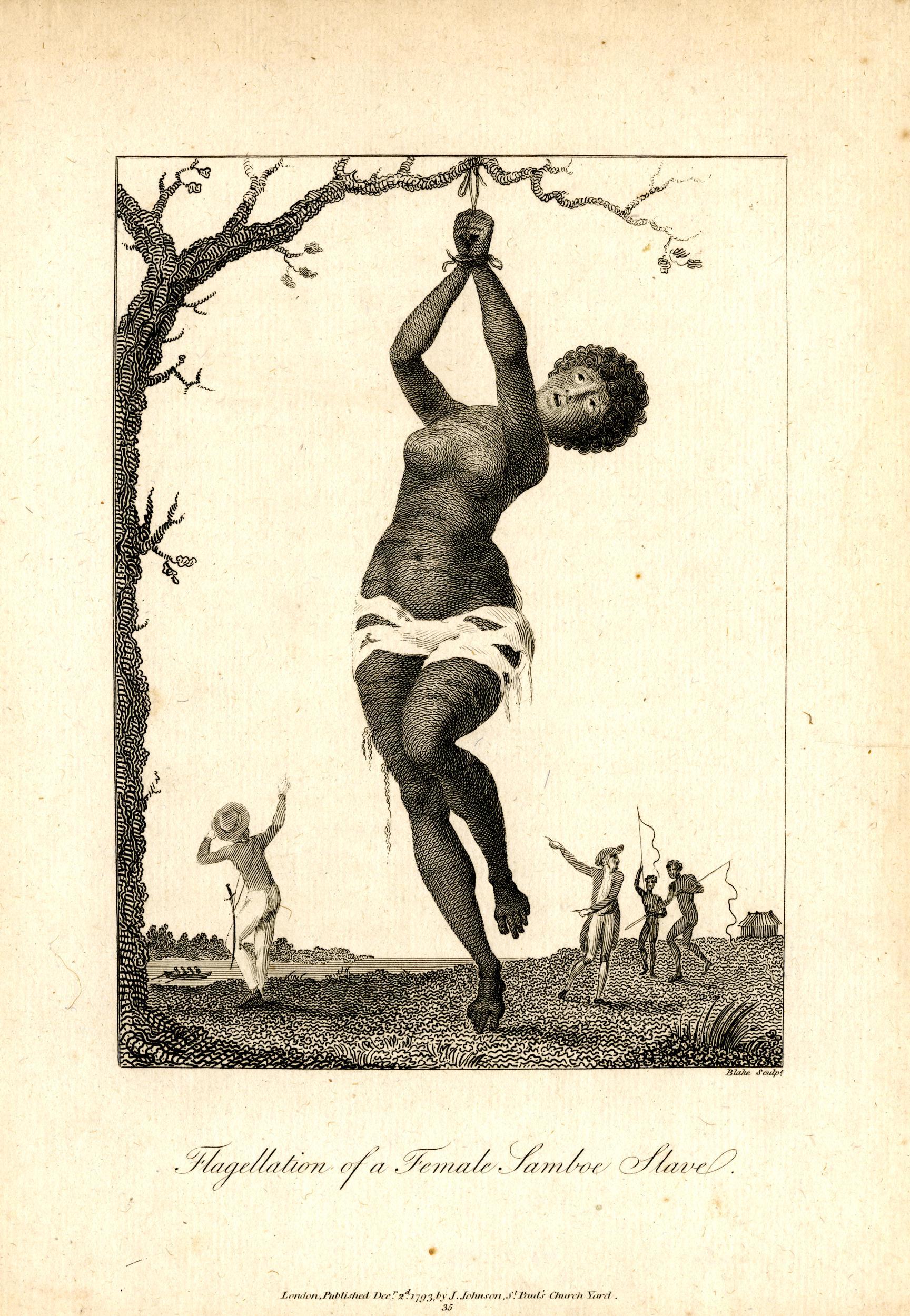

Engraving by William Blake of a punished enslaved woman

Engraving by William Blake of a punished enslaved woman© Wikimedia Commons

Stedman presents himself as both a participant and observer. Today, the book remains fairly specialist and doesn’t have a wide public or academic readership (it is never taught in 18th-century English literature classes, as far as I’m aware), yet almost everyone has come across the book’s illustrations.

The famous early romantic poet William Blake turned some of Stedman’s own drawings of Suriname into iconic pictures. The horrific image of an enslaved woman hanging from a tree is ubiquitous in demonstrations of the cruelty of slavery. The powerful visual impact of the book is as important as the text and the graphic nature of the illustrations is upsetting and confrontational. (3)

Quaco and Stedman: “My Boy Qwacco”

In Chapter 26 in a section entitled ‘Of Unhappy and happy Slaves,’ Quaco suddenly ‘speaks’:

The History of Qwacoo

my Black boy was still more Strange,

My Parents said he lived by Hunting and Fishing, from whom I was Stolen with two little Brothers when we were all very young & Playing in the Sands, being Carried/Alone/Some Miles in a Bag, I became the Slave of a King on the Coast of Guinea with many hundred more, who when our Master died, had all their heads Chopt off to be buried Along with him, Miself Alone Excepted, with other Children of my Age, And who being Bestow’d As Presents to the Different Captains of his Army, My new

Master again Sold me to the Captain of a Dutch Ship for some Powder and & a Musquet—(528-9)

Portrait of John Gabriel Stedman, painted by C. Delin, 1783

Portrait of John Gabriel Stedman, painted by C. Delin, 1783© Stedman Archive

Stedman voices Quaco’s story in his own words, presenting him as a full subject, the ‘I’ in the story, and a person in his own right, with parents and a history. He’s stolen by a King, somehow saved, bartered around, and significantly the story here ends with Quaco being exchanged for weapons to empower his new Master. He is ‘sold’ to a Dutch captain who journeys to Suriname where he ends up as Stedman’s own runner boy slave (his ‘futuboi’; he calls him ‘my Boy Qwacco” (336), who is almost always by his side during his four years in Suriname, and who then accompanies Stedman on his return to the Netherlands. As a young boy (my guess is that he’s about 14 but it’s unclear), Quaco experienced numerous traumatic experiences and his life with Stedman encapsulates a peculiar co-dependent Master/Slave relationship. His personal story resembles a slave narrative – Olaudah Equiano’s famous Interesting Narrative (1789) had been published a few years before Stedman published his book – and relates capturing, being sold on to slavery, and the frequent changing of hands. But most importantly it shows Quaco as a self-determined individual, ‘Miself Alone Excepted.’

The difference with the full-length Equiano book is that Quaco’s background story is just a few lines embedded in Stedman’s narrative. It is presented as the literary translation of Quaco’s own words, his ‘I’ supposedly in Quaco’s voice. However, Quaco’s original words will have been in Dutch, and the English here is already a translation of Quaco’s story from Dutch to English. Quaco’s oral narrative is translated into an English-written translation of his spoken words. And while Stedman grants Quaco his own story and ‘I,’ he subsequently translates it into his own reflection, not via an oral rendition but through a poem. Instead of an ‘authentic’ oral voice, Stedman moves it to the pinnacle of Western culture via a written poem. This is how the passage continues:

How hard must this not be Already, to be Drag’d over a Turbulent Sea to a Strange Country never more to Repatriate, let them be Used As well as even it is Possible—

The naked Negro Panting at Line

Boasts of his Golden sands & Palmy wine,

Basks in the Glare or Stems the tepid wave,

And thanks his Gods for the Good they gave,

Such is the patriots boast where e’er we Roam

His first best Country ever is at home. (529)

He begins by referring to the horrors of the Middle Passage and then writes a generic poem on ‘the Negro’. The personal story of Quaco has met a clear shift in pronouns: ‘I’ becomes ‘we’. The poem ends with an all-encompassing couplet that supposedly submerges Quaco’s story—”where e’er we Roam/His first best Country is ever at home.” It seems Quaco and Stedman have merged into a ‘we,’ longing back for ‘home.’ While Stedman distances himself from Quaco with poetic skill as opposed to unpolished narrative, the story of ‘roaming’ appears to unite the men. Significantly it is Stedman’s ‘we’ and not Quaco’s ‘I’. By drawing Quaco’s individual story into his poem, Stedman commits an act of literary colonialism; he literally subsumes Quaco into his own narrative.

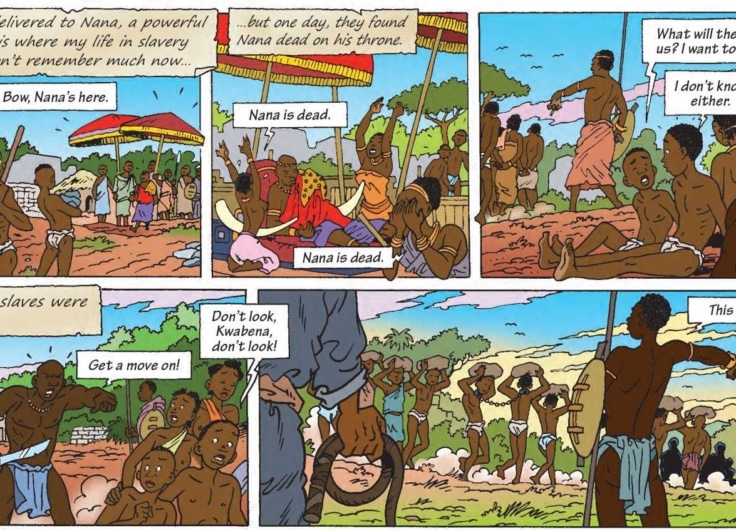

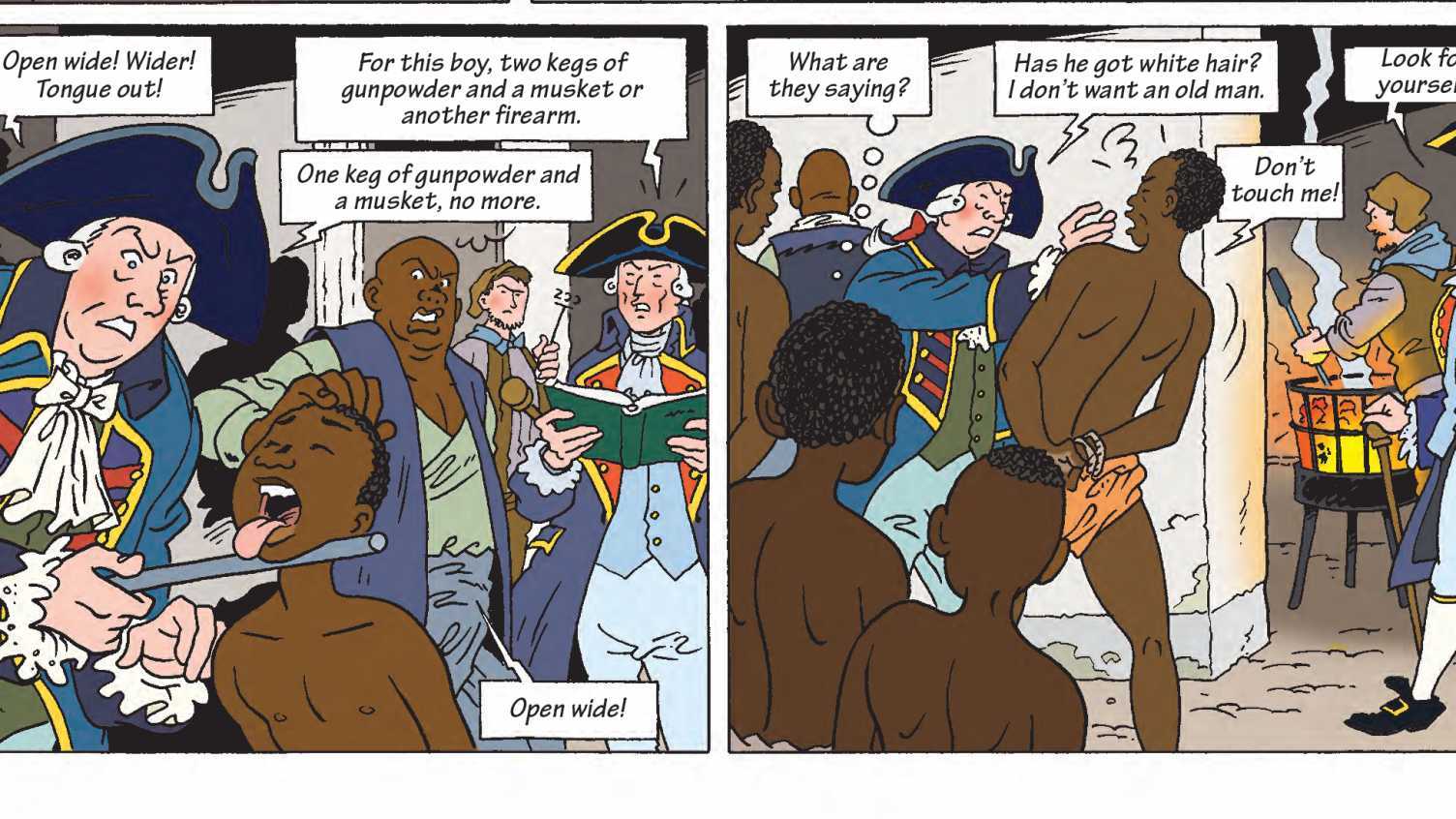

Illustrations from the graphic novel 'Quaco'

Illustrations from the graphic novel 'Quaco'© Ineke Mok and Eric Heuvel

Multilingual ‘Roamer’: “Who some datty … da Bony”

Stedman is a key figure in the transatlantic narrative of slavery and its legacies. Born in Austrian and now Belgian Dendermonde in 1744, son of a Scottish father and Dutch mother, grown up in Bergen op Zoom, dabbling in painting but opting for a career in the Scots brigade. Like his family, his life exemplifies the many interconnections between Europe and the Caribbean, what Paul Gilroy has termed the Black Atlantic. (4)

Hensleigh House in Tiverton, home of Stedman for the last ten years of his life

Hensleigh House in Tiverton, home of Stedman for the last ten years of his life© Tiverton Civic Society

In terms of academic legacy, Stedman has mostly been discussed from within an English tradition since his book was published in English and he spent the last ten years of his life as a wannabe farmer in Tiverton, Devon. Dutch researchers such as Ineke Mok have examined Stedman from within a Dutch perspective, and Roelof van Gelder’s acclaimed Dutch biography of Stedman, Dichter in de Jungle (2018) firmly locates Stedman in the Netherlands.(5) However, the Dutch and Anglo critical perspectives hardly meet — it’s as if there are two different Stedmans in his literary legacy. But with Stedman’s main ‘homes’ in the Netherlands, in Suriname, and in England, his ‘home’ is very much that of a multilingual ‘roamer.’ As far as I can tell, he spent 35 years in the Dutch Republic, four in Suriname, one year with his uncle in Scotland, and thirteen in England before dying aged 53.

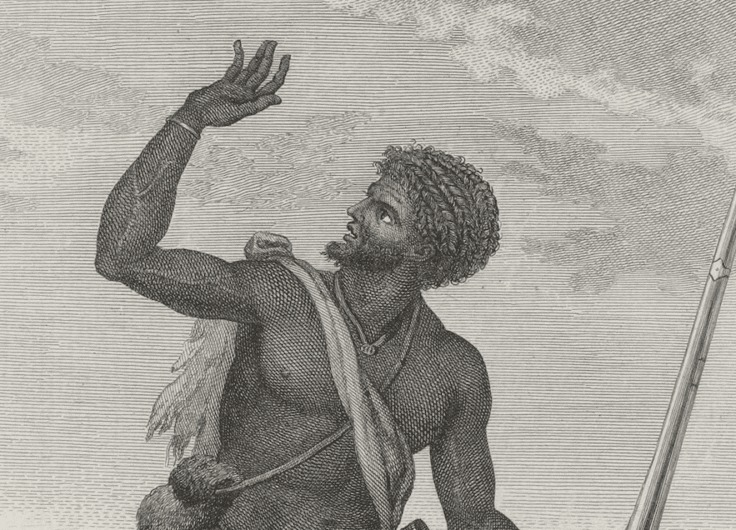

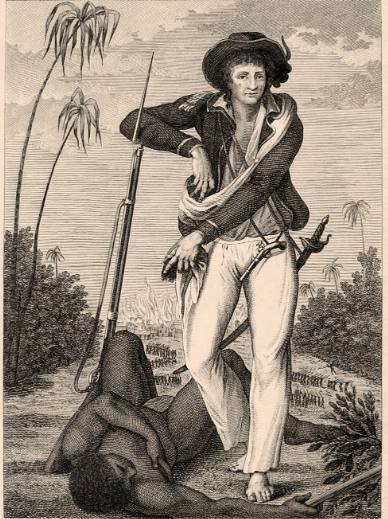

John Gabriel Stedman with a Maroon

John Gabriel Stedman with a Maroon© Wikipedia

The bulk of Stedman’s narrative details his many adventures and offers a unique portrait of life and conditions in Suriname in the 1770s. Captain Stedman embarks on the ‘expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Suriname’ as part of the Dutch Republic force to assist the Dutch plantation owners in their struggles against the Maroons (the escaped enslaved who live in the tropical forest) who raid their plantations. In true 18th-century style, he also records Surinamese flora and fauna, and he jumps from one topic to the next. Stories about his rivalry with his commander Louis Henry Fourgeoud, his many duels, life meanderings, drunkenness, sexual escapades, and his stubbornness fill the pages and we are left in no doubt that Stedman is a complex and difficult man. What stands out, though, is how he embraces new experiences and listens to others. After an elderly Black man tells him that in order to survive, he needs to learn to walk bare feet and swim daily in the river, he does. He acknowledges individual Black men and women and records their stories, often in their ‘own’ words. And he witnesses the cruelties of punishment of enslaved individuals and narrates those almost visually. The book becomes a catalogue of life in slavery for the enslaved and the plantation owners, with a special mention of the despicable Dutch plantation owner who is ‘nothing’ in his own country. Stedman has several near-death experiences himself due to the Suriname climate, its insects, wildlife, and rivers. He suggests that he is the only surviving officer of the original expedition, most soldiers and others succumbing to disease.

Stedman acknowledges individual Black men and women and records their stories, often in their ‘own’ words

In addition to this role of biased observer and recorder of Surinamese life, Stedman also participates in creating new transatlantic narratives and homes. He’s not much of a success as a soldier, firing his gun once aimlessly, in terms of fighting the Maroons. In fact, he ends up admiring the Maroon leader Boni so much that he builds a house just like his when he’s stationed at plantation Hope. And during one adventure, while in muddy blackface in the river, he is even mistaken for Boni, symbolically transitioning from a white occupying soldier to a Maroon. He uses the local language Sranan in this section of the text: “Who som ma datty…da Bony”(Who is there … it is Boni) (327). But the main change occurs via his relationship with Joanna, an enslaved woman. He narrates this Surinamese marriage in terms of a romance narrative, but with peculiar conditions. He cannot afford to ‘buy’ her, and when their son, Johnny, is born, he is the father of an enslaved child (the child follows the condition of the mother). When he writes the book (in the late 1780s), he describes this period with mother and child in almost Edenic terms.

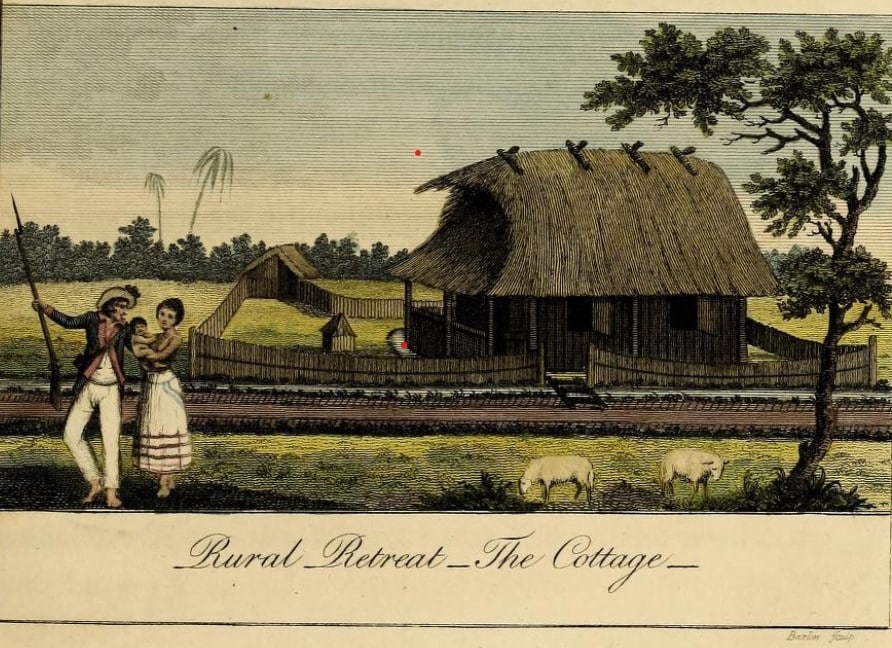

Stedman, Joanna and their son Johnny in front of their rural retreat, illustration by John Gabriel Stedman

Stedman, Joanna and their son Johnny in front of their rural retreat, illustration by John Gabriel StedmanIn front of a house that’s modelled on Boni’s, with his wife and son, Stedman includes his painting of a family portrait, in complete ‘huisje, boompje, beestje,’ (home and hearth) style. But there are many dissonances. It’s a home but it’s a copy, his wife and child are owned by a plantation owner, and he’s dressed in uniform, but barefoot. Above all, the question arises, where is his most loyal companion? Where’s Quaco? Presumably, he’s in the house, in the kitchen, and, significantly, not included in the family portrait. Present but absent. There are no illustrations of Quaco in the book.

Portrait of Joanna. Frontispiece to Stedman's Narrative of Joanna, an emancipated slave of Surinam, 1838

Portrait of Joanna. Frontispiece to Stedman's Narrative of Joanna, an emancipated slave of Surinam, 1838© Wikipedia

At the end of the campaign, Stedman returns to the Netherlands. In sentimental style, he begs Joanna to come with him, but she refuses, preferring to stay ‘home.’ He has bought Quaco for 500 Dutch florins earlier, and he finally manages to emancipate Johnny; he is “Suddenly Transported from Woe to happiness” (599) in spite of the criticism of his white peers who consider the emancipation of mixed-race children a weakness. He returns ‘home’ to the Netherlands not with his wife and child but with Quaco. Quaco once again has to start anew.

Erasure

Once back in the Netherlands, 35-year-old Stedman marries 17-year-old Adriana Wierts, conveniently mixing up events in his book. In his own narrative, Stedman asserts that his unnamed new wife helped him overcome his grief at Joanna’s death and that she resembled Joanna:

Not long had I been in this Situation, when now a young Lady whom I thought nearest Approache’d to her in every Virtue help’d to Support my Grief by becoming my Other Partner.—She was of a very respectable Family in Holland—(625).

Curiously, it seems he is trying to copy his life in Suriname by choosing a young woman who ‘Approache’d’ Joanna, and instead of naming her, he calls her “my Other Partner.” After his mother’s death, Johnny joins his father and Dutch stepmother in Maastricht. Because of the 4th Anglo-Dutch war (the members of the Scots Brigade have to choose between allegiance to either the Dutch Republic or England), Stedman decides to pack up his family and move to England and eventually to Devon.

As to Quaco, he gives him away as a present:

–I now also made a present of my true & Faithful Black boy Qwaccoo by his own Consent to the Countess of Rosendaal, to Which family I was under very high Obligations & who Since on Account of his Honesty & Sober Conduct not only Christned him by the name of Stedman at my desire but Created him to be theyr Butler, with a promise to take Care of him as Long as he Lived–& which was a Blessing I Could never have bestow’d on him myself—(620).

Ineke Mok and Van Gelder confirmed that Quaco was baptised Willem Stedman on 13 November 1785 at Castle Rosendael, near the city of Arnhem. Further research, however, reveals that once again, white promises about black freedom turn out to be hollow. The promise was not honoured and after an unspecified incident, Quaco travels to Batavia. We don’t (yet) know what happened to him there since he could not tell his own story. Stedman’s own words reveal the extent to which Quaco is no longer an ‘I’ with his own story.

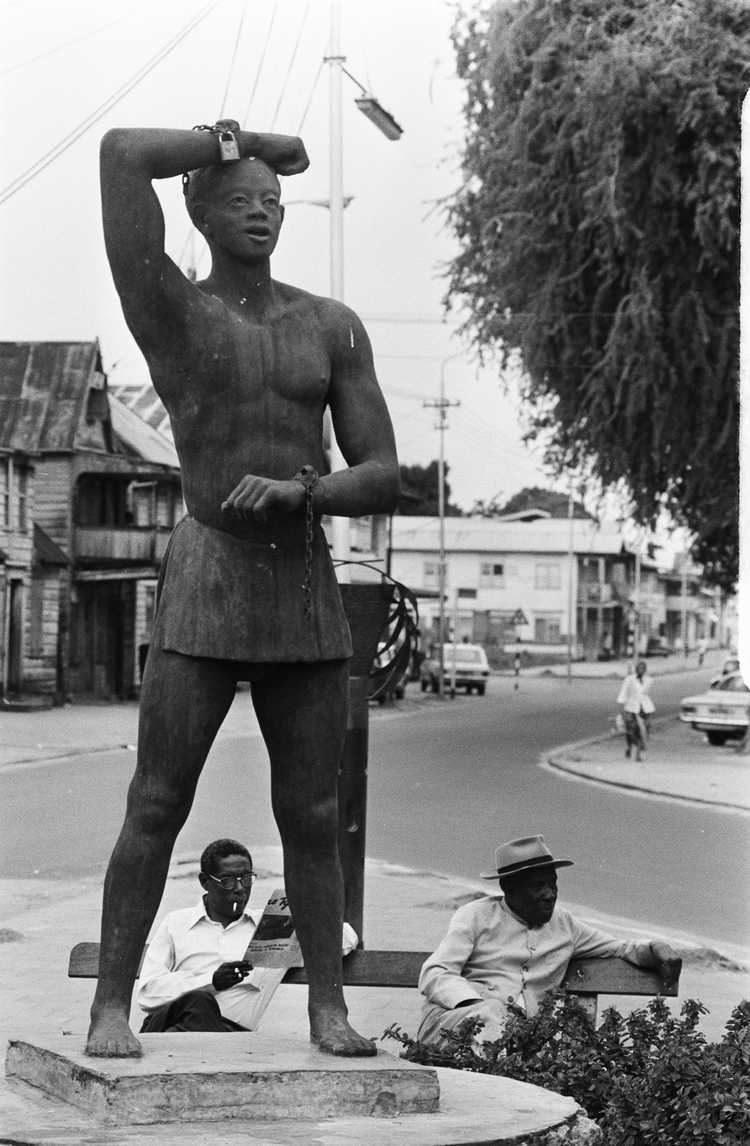

Statue of Quaco in Paramaribo, Suriname, source: National Archives

Statue of Quaco in Paramaribo, Suriname, source: National Archives© Wikimedia Commons

Quaco features in a list of presents from Suriname, starting with wax figures to Stadholder Willem V, and he suddenly moves on to his next ‘Surinamese’ gift. Quaco is once again exchanged, not for ‘powder and a Musquet’ but to settle a debt. While supposedly moving on ‘by his own consent,’ the baptism and name change were at Stedman’s ‘desire.’ In the process, he erases Quaco’s name and history, forcing him to take on his enslaver’s name. Stedman ends his roaming in Tiverton; Quaco wanders alone, “Miself Alone Excepted,” he says in his own story.

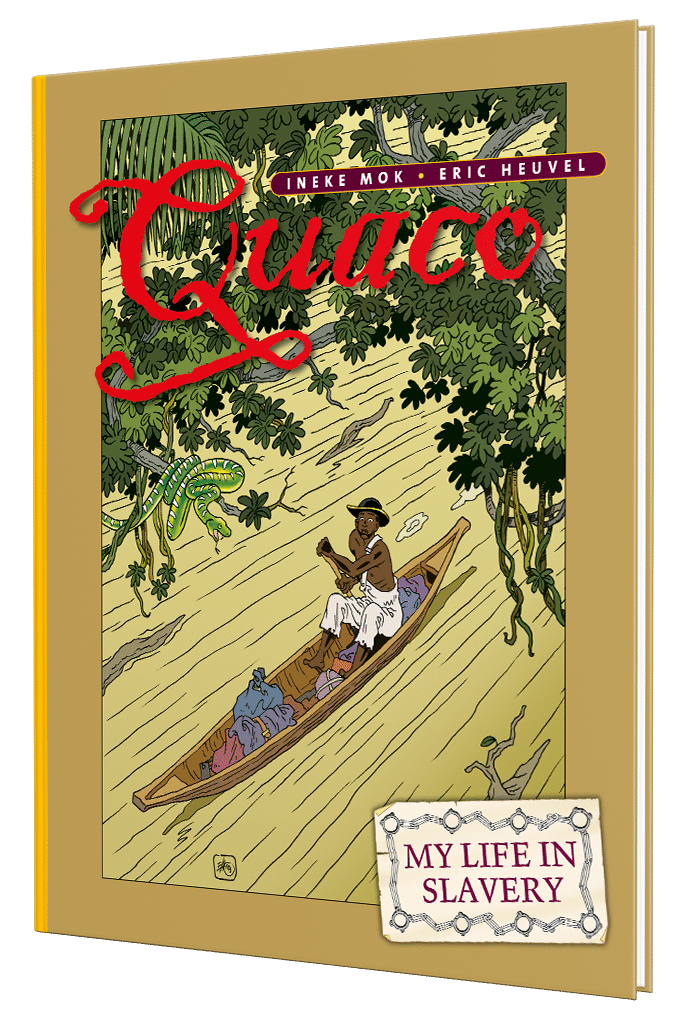

Cover of the graphic novel 'Quaco' by Ineke Moke and Eric Heuvel, translated from Dutch into English, by students of the University of Sheffield

Cover of the graphic novel 'Quaco' by Ineke Moke and Eric Heuvel, translated from Dutch into English, by students of the University of SheffieldIn Stedman’s narrative, Quaco’s story ends in Roosendaal; his in Tiverton; their shared history of transatlantic slavery rifts apart. “Excepted” in this exchange translates to Excluded and perhaps even Banishment from Stedman’s own search for home; his romantic vision in his poem where he and Quaco became ‘we’ is a colonial act, occupying Quaco’s ‘I’ into what he wants. I’d like to think that his idyllic home in Tiverton is an attempt to copy his garden of Eden at the Hope plantation, with a young wife who resembles Joanna, Johnny in his arms, animals on the farm, and perhaps even an attempt to plant some palm trees. But Quaco is missing.

Ineke Mok and Eric Heuvel gave Quaco a story and a face, and at the University of Sheffield, we aim to tell his own story in translation, without re-colonizing his individual voice for a romantic ideal.