How to Deal With a World That Is Becoming Increasingly Diverse and Colourful?

Vooruit Arts Centre in Ghent wants to keep its finger on the pulse of a changing society and keep reinventing itself. But what course should it take exactly? How should it deal with a world that is becoming increasingly diverse and colourful? In order to find answers to these questions, various artists and writers will be asked to help think about Vooruit’s future and responsibility for a year. They will write down the results in an inspiring essay entitled Vooruitopia. Hind Fraihi is the first author in the series. With Connection in confusion, she wrote a text that stimulates the senses, gives your moral awareness a boost and encourages you to think for yourself. Last year the Dutch version of her text was published as a book by Academia Press.

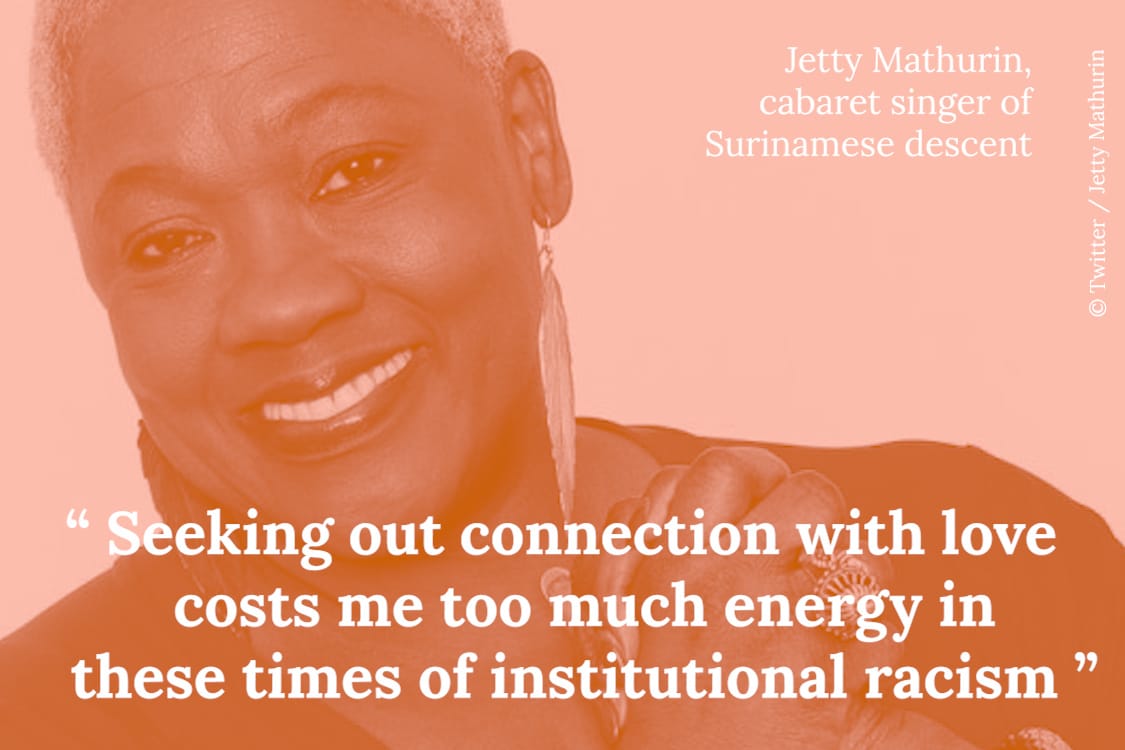

Take a good look around you the next time you’re at a play, dance performance or concert. You’ll be looking at a sea of white people staring at a stage on which other white people are giving it their all. The artist or group on stage will have been booked by someone at a cultural centre who, just like the majority of their colleagues, is white. The management will invariably be white, just like the board of directors. Cultural journalists and reviewers are almost all white. Only when you get down to the level of security and cleaning do you encounter the most ‘exotic’ names. Take another look around you as you’re walking home and notice the many languages, faiths, world views and colours moving around you on the same streets, the same buses and trams.

Now, just let that contrast sink in a bit. Why does this diversity – the lifeblood of so many towns and villages, the source of so much vibrancy, contrast, discussion, joy and laughter – end at the threshold of cultural institutions such as Vooruit? And what are the implications of this predominantly white environment for our vision of culture (the word ‘our’ being used inclusively here)?

The answer lies in what seems to be the eternal cycle of culture. Theatre, dance, music, literature … all seem to draw a primarily white, progressive and highly-educated audience. Their taste determines the offering. Their every beck and call is heeded by an army of programmers, theatremakers, dramaturges, musicians, writers, poets and choreographers, who in turn tend to be white, progressive and highly educated. The dominant vision of what quality art is, is in fact limited to the opinion of a small, privileged club. That in 2017 people still speak in terms of ‘minority literature’ and ‘ethnic theatre’ gives an indication of how whiteness is still seen as the norm. How everything that is different (read: non-Western) must be labelled to differentiate it from the dominant culture.

However, a grain of sand has become lodged in the mechanism of the machine that keeps the old cycle going. A tiny, crystalline crumb that is nonetheless growing and growing, and that will eventually cause the machinery to jam and splutter and billow smoke. The white audiences of the cultural institutions are visibly ageing. It is only a matter of time before the art world completely loses touch with the world that exists outside its doors. Dianne Zuidema, Director of Amsterdam’s City Theatre: “A white audience is not yet seen as a problem everywhere, since numbers are not yet in decline. But within five to ten years this is guaranteed to be the case if we don’t address the problem. But, this argument aside, we need to work a lot harder to reflect our mixed society.”

Charles Esche, Director of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, made a bold statement some years ago: “We have to become irrelevant to our current audience.” The Dutch-Surinamese theatremaker Quincy Gario picked up on this: “He means middle-aged white people of a certain social class who now represent the largest audience. This is not the future. This isn’t even the present. The institutions therefore have to commit self-sabotage. They have to ensure that what is happening speaks to a new audience.”

This realisation is slowly but surely penetrating the sector. Diversity seminars (another outdated notion) are being organised. There’s a lot of debate, opinions and chitter-chatter. Here and there, serious attempts are being undertaken to inject more colour into the art world. Simply throwing open the doors to others in society is not enough, however. It’s not enough to write in a role for a token foreigner, to book that one black, female comedian or programme a reggae band. This is self-satisfying policy that doesn’t have any impact on the dominant culture.

When you hear the word “bounty”, your first thought may well be of the tasty dark chocolate treat with a white coconut filling. The term is also used to refer to people of colour who ‘act white’. Within their own culture, this term brands them as defectors, collaborators. The question is whether so-called bountys adopt this behaviour of their own volition. Could it instead be a kind of survival reflex in order to make it within a certain environment? These days, having a little colour to your skin is no barrier to employment. In fact, a healthy dose of ‘diversity’ makes your organisation hip and progressive. At the same time, it is expected that you assume a completely white way of thinking in order to ‘fit within the organisation’. Mimicry as a means of survival.

Another flavour of bounty is to be found almost exclusively in the art world. A person of colour will start to behave in line with the clichés that the West maintains with respect to the person’s own culture. A white audience comes to so-called ‘ethnic’ shows with a predetermined notion of what they can expect and, what’s more, that’s actually what they want to be served up.

A form of tunnel vision that goes back to the darkest pages of recent history: colonisation. In order for the rising European powers to justify their limitless drive to conquer, the colonised peoples had to be presented as underdeveloped savages. They peddled the excuse, ‘être colonisé, c’est d’abord être colonisable, non?’. This perfidious intertwining of science, geopolitics and blunt commerce resulted in one of the most shocking phenomena in recent European history: Le Zoo Humain, the human zoo. There the civilised white man could go and gape at the ‘wild savages’, who had been plucked straight from the jungle by heroic explorers. Even as recently as the 1958 Brussels Expo, foreign natives would be made to demonstrate to spectators how much more civilised the generous colonisers had made them.

A person of colour and their culture have to satisfy the stereotypes that the West has invented. The old cliché that ‘black people are good dancers’ may at first sound positive. However, it ultimately betrays an exotic and oriental view of this culture. A form of generalisation that dates back to the descriptions by European colonialists who tried to sum up a vast and exceptionally diverse continent with scant few terms. The guiding ideas being childishness, naivety and raucousness. A clear demarcation of qualities so as to maintain a definite distinction between white and coloured people.

Those who don’t perpetuate the stereotypes face difficulty. This was the experience of the Dutch-Moroccan creative entrepreneur Chafina Ben Dahman when she was consulted on a film featuring a Moroccan boy. “At the end of the project the filmmakers said to me: the characters are not Moroccan enough. The advice I had given them was based on my own life experiences, but apparently it didn’t confirm the stereotypical story they wanted to hear. There was no room for my perspective. I really had to create it myself.”

In recent years, more attention has been paid to non-Western art and to artists of colour. Too often, this interest is still based on a combination of exoticism and stereotypes, however. The effect is to stifle the artistic aspirations of any new cultural avant garde right off the bat. By having to conform to the Western view of their culture, these young talents are forced to break with their own identity. In order to be ‘Moroccan enough’, for example. But what does that even mean? Target figures and absurd expectations should not stand in the way of the development of a broad range of forms of individual artistic expression that challenge, confront and question the dominant culture.

Diversity can’t be a target; it’s already a reality. We live in a society that is multifaceted and characterised by difference. Yet also by sameness. Humanity is singular in its multiplicity. La singularité plurielle, it brings with it so much confusion to be resolved.

Ewa ja is street slang. Here it means, roughly, ‘so be it’. Slang meaning ‘the (other) young people’.

I have always seen diversity as an organic process. Like a grapevine, it grows by itself, at a rapid pace and sometimes flourishing in the most unexpected places. It puts down roots, it branches out, blossoms and bears fruit. There’s no use trying to prune it into a certain shape. You can trim it, replant it elsewhere or hit it with herbicide but it will always grow back. Diversity has a life of its own. It doesn’t need any self-proclaimed experts in order to grow into something magnificent.

Take street slang, for example, the means by which hip young people differentiate themselves from adults and wannabes. While previous generations borrowed their coolness from English-speaking culture, today’s youth colours the Dutch language with Arabic, Berber or Turkish. They introduce words like drarrie, flous, shmetta, habiba, rwina and wayaw. Their own music is pivotal in this process. Hip-hop, rap, frithop, nederhop, street rap, mocro rap, the list goes on. The wide range of terms itself says a lot.

Anyone with teenagers or children in their environment will no doubt recognise the tune: Habiba, Habiba / Waarom stress je mij a zina, a zina? / Ik ben op straat, ik ben met dieven, met dieven / Ik denk niet eens aan liefde / ben gefocust op verdienen / Dus word niet te verliefd, nee. The Dutch rapper Sofiane Boussaadia, better known as Boef, grew up on the streets and in institutions. Today he is a hugely popular artist with a gigantic following on social media, which is what led to his breakthrough into the mainstream. Now he now performs to large audiences at traditional festivals and platforms. In doing so he is exposing their traditional audiences to a mote of colour, however briefly. He has paved the way for other rappers, such as Soufiane, Eddyani, Said Boumazoughe and Saladine Ibnou Kacemi of SLM. They all have one thing in common: they have gained success primarily through the many thousands of followers and sometimes millions of views that they have accrued on social media.

Culture is, thankfully, volatile and remarkably subject to new influences and technologies. The new generation of artists of colour is no longer dependent on the arbitrary influence of culture vouchers, reviewers, self-proclaimed experts and teachers. Art is now developing out on the streets rather than within the walls of educational institutions. Social media platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, Facebook and Twitter are the primary vehicles for today’s creative youth. Many hundreds of small communities are being created online, going further than just art, each displacing a brick in the wall of the dominant culture of society. It’s only a matter of time before the wall comes down completely.

The key to this movement is its accessibility. For decades, the cultural world has puzzled over how it might bridge the gulf between itself and the majority of the population. Social media has erased this quandary in one fell swoop. Using one’s own time, money and other resources, one can now present one’s message to whomever is open to it. Free of interference, subsidy rounds and the obligation to pander to the audience. Art has never been as democratic as it is today.

The doors of the cultural institutions, now open just a crack after years of pushing, can finally be bypassed entirely. Young talents are creating their own vlogs, using their smartphones to upload their own videos to their own YouTube channels. They are starting their own production houses, cultural platforms and art spaces. They are reaching their own audience with their own message. Their own success is encouraging other young people from the same bottom layer of our towns and municipalities to take their own shot at success. Bling is no longer only gotten through pimping or dealing, but through rapping, singing or making art.

For these young people, there is no longer a question mark hanging over their identity. Their identity is Belgian, but at the same time many-layered and many-coloured, global and universal. These young people about whom everyone has an opinion, despite not knowing them. These young people have a message:

Wait a minute. Why does everyone want to go their own way? To answer that question we have to return to the wave of migrants from the sixties and look at all aspects of the situation. What went wrong? This is the kind of matter that deserves a truth commission. Not for the sake of blame, but for the sake of progress. To find the intersection of separate roads and worlds. The crossways of opportunity, rights and obligations. The moral master key, if you like. It is a search for a deeper, more layered truth that will at first cause confusion but ultimately serve to connect us in heart and mind. In education and art, for example: a Vooruitopia.

Utopianism was also the driving force behind the Russian Narodnik movement. Nineteenth-century intellectuals who literally went to the people to educate them, to teach them to understand and appreciate their own value. Their vision can be combined with the pragmatism by which the Danish Grundtvig became the father of the ‘folk high school’. These institutions democratised education in Scandinavia and their benefits are still being reaped today. The same is true of art, and in particular one of its ‘cardinal sins’, literature. “I owe my whole life to books from libraries’’, says best-selling writer Zadie Smith in a warm defence of local libraries. A book around the corner, for everyone.

Knowledge and art should be brought to the people, including those in working-class and forgotten neighbourhoods, making these ‘no man’s lands’ ‘someone’s lands’. Educational and art institutions could be assets. Centres that know their role in a world where everyone is different and can’t be simply swept under the carpet. Centres of wonderment up against which even the most seductive of radicalisation techniques holds no power and is left to disappear into the history books. Centres to which the forgotten might owe their lives. In public squares, around the corner. Little Vooruits that bring art to the people in a country where ‘normal’ hasn’t existed for a long time, and where confusion is the only uniting factor. Where connection confuses. It is a pertinent choice in favour of the irrational. In favour of dreaming, dancing, singing, painting, writing. That which can be held onto, discovered. Let go. Ripped out.

Come on, Vooruit! Ewa ja!

Connection is a word on many people’s lips in these turbulent times. The social fabric is crumpling under ‘multiple dualities’. Debates have given way to virtual wars. Online, the media stokes the fire of one scandal after another in the hope of gaining a bigger market share of clicks. The increasing focus on the ‘I’, the total retreat into the cocoon of the self, brings with it a deep-seated coldness that makes empathising with others almost impossible. Our society needs connection again, it needs common ground. This is hardly news. It’s been said for quite some time now. And for quite some time we have been looking to the cultural world to bring about this connection.

But to foster connection one must first of all be relevant. To everyone. So, how does the cultural sector win back its relevance?

By making drastic changes, by completely upending the system. The alternative is to keep on tinkering at the sidelines of an accelerating world. As for the privileged, those who have been in control up until now, it is time for them to hand over power. To dare to give space and resources to artists who have not walked the usual path. Yolande Melsert, Director of the Dutch Association of the Performing Arts, realises that this is not the most obvious path: “Yes, at times it will hurt. We need to get better at sharing resources more fairly, and you have to be ready for that.”

Those wishing to remain relevant must dare to be vulnerable. To hit the streets once more. There’s no point in locking yourself away within the walls of your art fortress while the air gradually becomes stale. Let Vooruit be the point of departure for an Art Train. A band of the bold and the colourful travelling around from centres to forgotten neighbourhoods.

The Train enters into debate with young revolutionaries armed with street wisdom who have the courage to call your culture into question. Together they bring an end to the paradigms and dogmas that for so long have determined what is art and what is pulp. Everything is turned on its head. Art from outside Fort Europa is no longer relegated to ‘African Film Week’ or ‘Arabian Poetry Weekend’. The Art Train sets off with saddlebags full of literature, films, children’s books, drawings and more that appeal to the identity of all young people.

Connection also means security. Only someone who feels safe and secure can trust others enough to open up to them. But security means more than soldiers on the street and crush barriers around the flea market. If we want to come together to extinguish the burgeoning flames of radicalisation, we first have to show courage. Courage to look into the dark heart of Islamist radicalism. There – strangely enough – one finds poetry. Anyone wishing to understand the recruitment of IS fighters in particular and jihadism in general be careful not to underestimate the power of poetry. Jihadi poetry is a widely used recruitment tool on the internet. And it is not seldom that this poetry speaks of love.

In the Arabic world, poetry is seen as the highest form of art and culture. And this was the case even prior to the arrival of Islam. The role that poetry played in the spiritual lives of the Arabs was so great that even the Koran was penned in poetry. The holy book of the Muslims is known for its remarkable verbal artistry, a fine example of rhyming prose in verses with no fixed metre. The Koran stimulated the continuation of a long and rich tradition of poetry in the Arab world and served to add further weight to the prestigious status of the word.

But poets have a practical purpose, too: a poem makes it easy to learn a message by heart and subsequently pass it on. L’histoire se repète, as we were told at school. The lesson received by jihadis, however, is that it is not only history that repeats itself: the word is to be repeated, like the reverberation of a heart that never stops beating.

Our counter-narrative pales in comparison. Our education system is still hung up on the narrow Western view of the world. Navel-gazing is repackaged as learning material. Pupils with non-Western roots learn hardly anything about how rich the culture of their parents and grandparents was. You won’t find any mention of the likes of Nagieb Mahfoez, Fatima Mernissi or Nawal el Saadawi on the curriculum. The task of making the link with one’s own cultural background is left to Koran schools, mosques, TV channels subsidised by Wahhabist regimes and internet forums. The world view that these young people are left with dates back to the Middle Ages.

Culture could be one of the pillars on which our counter-narrative is built. With the Art Train we can change the world (or at least Ghent, for starters). By letting go. Of dogmas, diversity seminars, minority literature, ethnic theatre and the tastes of an ageing, white audience. Of overbearing management, clichés, exoticism, imposed systems and art forms. By instead offering young people (of colour), through art and culture, a strong alternative plan that takes their individuality into account. By rationally choosing in favour of the irrational. In favour of doubt and a voyage into the unknown. In favour of imagination. The poetry of life and so much confusion.

And then, finally, we will feel it. Connection.

Sources

• De Morgen, Single van Antwerps duo SLM met positieve boodschap: “Op het Kiel loopt het stampvol talent”, Pieter Dumon, 22 september 2017

• De Morgen, BSO is niet het verdomhoekje van de samenleving, Fernand Van Damme, 6 november 2017

• De Morgen, Anderson .Paak: Dit moet hét concert van Pukkelpop 2016 zijn geweest, Sasha Van der Speeten, 20 augustus 2016

• De Standaard, Arabisch in de Antwerpse jongerentaal, Karin Vanheusden, 1 april 2015

• De Standaard, Een zee van witte mensen, Tunde Adefioye, 5 augustus 2017

• De Standaard, De gekleurde schrijver blijft een witte raaf, Maarten Goethals, 3 november 2017

• De Standaard, Gedaan met middenklasseproza, Maarten Goethals, 3 november 2017

• De Standaard, Aan alle blanke mannen: maak plaats!, Nick De Leu, 8 november 2017

• De Tijd, Imperfect, Hind Fraihi, 6 juli 2017

• De Tijd, Miskende Rijkdom, Hind Fraihi, 1 oktober 2016

• De Utrechtse Internet Courant, Melody Deldjou Fard: ‘De culturele sector is nog te eenzijdig’, Fenna Riethof, 6 mei 2017

• De Volkskrant, ‘Straattaal is ook Nederlands, dus keur het niet snobistisch af’, Shantie Ramlal-Jagmohansingh, 5 november 2012

• DeWereldMorgen, Quincy Gario en Rachida Aziz over de verblindende witheid van de podia in Vlaanderen en Nederland, Christophe Callewaert, 12 augustus 2017

• Fraihi Hind, Les van de eeuw: Poëzie en moslimextremisme, Lezing in de Vooruit op 14 februari 2017

• Libération, Marianne et le garçon noir, Léonora Miano, 30 augustus 2016

• Gazet Van Antwerpen, “Clichés over Marokkanen, maar dan op niveau” Nora Gharib Saïd Boumazoughe, Maaike Floor, 25 februari 2017

• Gazet Van Antwerpen, Zo verovert jonge – en onbekende – Antwerpse rapper YouTube in zes dagen, Sam Reyntjens, 8 september 2016

• Gazet Van Antwerpen, Bijna 200.000 views op amper één week voor ‘Ewa Ja’, 29 september 2017

• Gazet Van Antwerpen, “Het Kiel is ons Hollywood”, Rebecca Van Remoortere, 3 oktober 2017

• Miano Léonora, Marianne et le garçon noir, Les éditions Pauvert, 2017

• NRC, Theatersector: ‘We moeten de macht uit handen durven geven’, Carolien Verduijn, 18 september 2017

• NRC, Het is altijd Eva, Emma of Floor, en zelden Fatima, Thomas de Veen, 13 oktober 2017

• Trouw, Zwarte acteurs zijn klaar met het witte theater, Sandra Kooke, 6 oktober 2017

• Trouw, Waarom rapper Boef de nieuwe James Dean is, Hans Marijnissen, 15 november 2017

• VRT NWS, “Een zebi? Dat is dat ding waarmee Harvey Weinstein graag zwaait”, Jos Vandervelden, 28 oktober 2017