Rotterdam used to be a tough industrial city. Not any longer. It’s now got the energy of New York combined with the liveability of Copenhagen.

‘People are separated by distance but not by spirit,’ reads the sign above the steps leading down to the metro. It is a quote by Erasmus, greeting people as they arrive at Rotterdam’s sleek new Central Station.

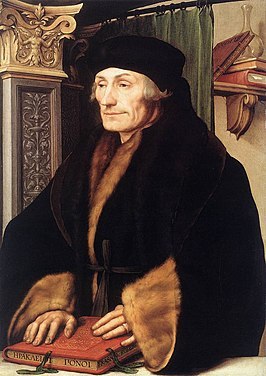

Portrait of Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam by Hans Holbein de Jonge, 1523

Portrait of Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam by Hans Holbein de Jonge, 1523© National Gallery, London

Born in Rotterdam in about 1466, the gentle humanist scholar was a citizen of the world, but Rotterdam has claimed him as one of its own. He is everywhere – his signature picked out in blue neon on top of the Erasmus hospital, his statue in front of the Church of St. Lawrence, his words reproduced on a monument near the Lijnbaan. When a new bridge spanning the River Maas was built, it was called – you’ve guessed it, the Erasmus Bridge, although locals like to call it ‘The Swan’ because of its distinctive profile.

And yet there isn’t much left of the Rotterdam that Erasmus would have known. On 14 May 1940, the Luftwaffe sent 90 warplanes loaded with bombs over the city. In just 15 minutes, the heart of Rotterdam was reduced to rubble. One thousand people died, and 85,000 were left homeless. Almost nothing survived, apart from the old church and one tall waterfront building called the Witte Huis. The rest was gone.

Rotterdam after the bombing of May 1940

Rotterdam after the bombing of May 1940© U.S. Defense Visual Information Center

The city centre was rebuilt from scratch, with clean, modern apartment buildings, efficient highways and Europe’s first pedestrian shopping street. Some admired it; others complained it was a city without a heart.

You have to go outside the destroyed zone to find relics of the older city. There are some minor architectural gems that survived the bombs, like the Huis Sonneveld, built for the director of Van Nelle’s tobacco division by the same architects as the Van Nelle factory where he worked. It’s a subtle modernist house with sleek furniture, vintage gadgets and sunny terraces. As you wander around, the audio guide recalls details from family life that expertly bring the house back to life.

Rotterdam by night

Rotterdam by nightWhen I first visited Rotterdam in the 1980s, Rotterdam lacked the artistic energy of Amsterdam or the quiet beauty of Delft. You could wander down the Lijnbaan shopping district (no longer quite so innovative, as hundreds of new shopping centres had copied the style), take a boat trip through the port and ride to the top of the Euromast. You had the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen for art, the old harbour at Delfshaven for atmosphere and Zadkine’s monument to the bombardment as a reminder of what caused the city to look so new. And that was about it. Rotterdam was a working city, and that was that.

But then something happened. A few years ago, I started to notice enthusiastic articles about Rotterdam. It was the one of the “52 places to go in 2014,” according to the New York Times. It was coolest city in the Netherlands, the Wall Street Journal announced in 2016. Really? Rotterdam? I had to go.

Rotterdam Central Station

Rotterdam Central StationWhen I made it back in the winter of 2016, I barely recognised the place. There was a new station designed by Benthem Crouwel Architects with a gorgeous sloping roof that was like a huge arrow pointing in the direction of the city. A short walk brought me to MVRDV’s astonishing Markthal apartment complex built like a giant shell above a food market. And another five minutes took me down to the transformed waterfront where a 1970s tropical swimming pool had been converted into a restaurant.

Cube Houses

Cube HousesThe biggest shock was the city skyline. Back in the 1980s, the architecture was fairly unexciting, apart from a cluster of odd experimental buildings around Blaak metro station, including Piet Blom’s quirky yellow tilted Cube Houses, built on a bridge across a busy main road. Thirty years on, the tilted houses now seem a bit dated, a vision of the future that didn’t work out.

But now there are dozens of adventurous new buildings dotted around the city, like the tower designed by Daan Roosegaarde that absorbs smog particles and the bright yellow Luchtsingel pedestrian bridge built as a crowdfunded initiative to connect forgotten urban spots cut off by busy roads. Even the new McDonald’s restaurant on Coolsingel is a stunning glass building designed by Mei Architects on the site of a derelict 1960s structure.

Smog tower of Daan Roosegaarde

Smog tower of Daan RoosegaardeRotterdam now feels like a city on the move, with ambitious plans for the coming decade, including a futuristic wind generator combined with apartment complex called Dutch Windwheel. So how did Rotterdam – once ranked as the worst city in the Netherlands to bring up a family – get to be so hip?

If you don’t like it here, fuck off

Rotterdam Mayor Ahmed Aboutaleb

Rotterdam Mayor Ahmed Aboutaleb© The Dutch government agency for information to the public and press

It could be down to the mayor. Born in Morocco, Mayor Ahmed Aboutaleb has run the city since 2009. A virtual Aboutaleb explains his vision for Rotterdam as you enter the small urban exhibition below the tourist office. Rotterdam is for everyone who lives there, the digital figure explains.

You see the results of this vision in the new Rotterdam Museum where a sizeable part of the building is devoted to the one-half of the population with foreign roots. ‘Wherever our roots may lie, almost all consider ourselves Rotterdammer,’ the explanation reads. You get the point when you look at a photograph of a large smiling Turkish family with everyone dressed in traditional Dutch costumes.

Aboutaleb’s vision might be inclusive, but that doesn’t stop him being tough on extremists. ‘If you don’t like freedom, just pack your bags and fuck off,’ he declared after the attacks on Charlie Hebdo.

The sociologist Willem Schinkel, who teaches at the Erasmus University, pinned down the city’s distinct identity in a 2013 talk titled Loving a city without a heart. ‘Amsterdam is an easy city to love… Rotterdam on the other hand is hard to get because it never really surrenders and it always keeps its distance,’ he argued. ‘But it’s precisely that unapproachability that opens up the possibility of a creative love affair, one where you have to always make an effort.’

And if you don’t, then you know where to go.

Manhattan on the Maas

It took me a while to realise that the real action was happening on the south side of the river in the district called Kop van Zuid. Back in the 1980s this was an industrial area that was hard to reach from the city centre, but it’s now connected by a graceful suspension bridge, the Erasmus Bridge, designed by UNStudio. As you cross high above the river, the view could almost be New York. And so it is no surprise when you come to Hotel New York on the other side of the river.

Erasmus Bridge

Erasmus BridgeThe hotel occupies a brick building from 1901 that originally served as the Holland America Line’s headquarters. It stands on a symbolic spot at the head of the island looking out to sea. After the last transatlantic liner sailed off in 1971, this docklands area became an industrial wasteland. By the late 1980s, the empty HAL office building had been taken over by a few dozen squatters.

Hotel New York

Hotel New YorkBut then something happened that changed everything. The local entrepreneur Daan van der Have was walking through the neighbourhood with the musician Berry Visser when they came across the dilapidated HAL building in the middle of industrial wasteland. Visser reflected, ‘This would make a beautiful hotel’. Van der Have jumped at the idea and brought in the designer Dorine de Vos to shape the makeover.

The restaurant of Hotel New York

The restaurant of Hotel New YorkDe Vos took her inspiration from the mix of old and new elements in contemporary New York hotels. She kept the wooden floors and added nostalgic touches like a pile of three dusty suitcases at the entrance, ship models in the corridors and giant photographs of Rotterdam in the bedrooms. A vast restaurant was added in vintage liner style, complete with a replica steering house, to create a bustling, noisy dining hall where Rotterdammers like to meet.

The hotel’s isolated location was solved by introducing a water taxi service. This has grown into a thriving business with dozens of fast yellow speedboats nipping between landing stages along the waterfront.

The hotel now attracts a cosmopolitan mix of executives, tourists and artists. In 2004, the Dutch singer Anouk shut herself away in room 101 to work on her album Hotel New York. She created several hit songs in the hotel room, including the ballad ‘Lost’.

Kop van Zuid

Kop van ZuidOnce the hotel had established itself, the Kop van Zuid slowly started to develop. But it needed a bridge to link it with the city centre. The harbour bosses weren’t keen, but Rotterdam’s urban planner Riek Bakker refused to give up. Nicknamed Baas van de Maas (Boss of the Maas), she realised she would have to be tough. ‘They said I was mad,’ she recalled. But she got her way in the end. The Erasmus Bridge opened in 1996 and the neighbourhood took off.

There’s now a real buzz on the south side of the river. It’s like Copenhagen on steroids. The new buildings include OMA’s colossal De Rotterdam building of 2013 and Mecanoo Architecten’s sleek Montevideo tower. You see converted warehouses, startup companies, a huge food hall called Fenix Food Factory, lunchtime joggers, multinational offices, hipster coffee shops and a craft brewery. Giant cruise ships now regularly moor on a waterfront that was a wasteland just twenty years ago.

Outside Hotel New York, the open space known as Kop van Zuid has been imaginatively landscaped to create an urban park with a view of the River Maas as thrilling as a New York waterfront. The new footpaths even have names borrowed from Manhattan like Madison and 5th, just to hammer home the point.

Lost Luggage Depot, sculpture by Jeff Wall

Lost Luggage Depot, sculpture by Jeff WallIn 2001, the Canadian artist Jeff Wall added an evocative waterfront art work called Lost Luggage Depot. The cast iron sculpture represents piles of suitcases, bags and other possessions waiting to be loaded onto a liner.

the HAL liner SS Rotterdam, once the flagship of the Holland America Line, today a hotel.

the HAL liner SS Rotterdam, once the flagship of the Holland America Line, today a hotel.A ten-minute walk along the waterfront brings you to the former HAL liner SS Rotterdam. Once the flagship of the Holland America Line, the luxury liner has been turned into a hotel by the owners of Hotel New York. They have lovingly preserved the romance of a transatlantic liner with staff in smart white uniforms, starched tablecloths and cabins in 1970s style.

The old industrial area is now dotted with trendy restaurants, bars and cafes. I dived into a huge converted warehouse called Posse filled with vintage furniture, old typewriters and erotic photographs. It was a bit seedy, a bit brutal. Typical Rotterdam in other words.

A local asked where I was from. Brussels, I said. He told me about the square near Posse that was now called Deliplein. ‘It used to be the red light district,’ he said. ‘It was a dangerous place. You could end up with your throat cut,’ he recalled. Now hipsters go there to get their beards cut.

On previous visits to Rotterdam, I hardly noticed the river. But it’s now the heart of the city. The city has turned its river into one of the great waterfronts of the world, with a walking and cycling trail called the Nieuwe Maas Parcours that runs along both sides of the river over a distance of 28 kilometres.

The river Maas in Rotterdam

The river Maas in RotterdamStanding on the Kop van Zuid, looking across the wide river mouth, it’s easy to imagine liners setting off for America carrying Europe’s poor, hungry and oppressed migrants. This used to be a place where people left for a better life. Now Rotterdam is a cool destination, a city with a heart.

The city even has a new motto. Make it happen, it says, in English. It is better, I think, than Amsterdam’s controversial (and now abandoned) branding exercise I amsterdam. More like Obama’s, Yes we can.

Yes, they did.