Hugo Grotius, Patriarch of International Law

He is best known as “the man who escaped from prison in a chest of books”. But thanks to biographer Henk Nellen, we know that the seventeenth-century man Hugo de Groot or Grotius was more than that: he was also an internationally important legal scholar, a policymaker of the Republic and a transitional figure who heralded the secularization of our worldview.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the small and then neutral Netherlands – crushed as it felt in between the European superpowers Germany, France and Great Britain – emphatically presented itself as the birthplace and thus the guardian of international law. That fame went back to the seventeenth-century legal scholar Hugo de Groot or Grotius (1583-1645). His Mare Liberum of 1609 laid the foundation for the idea that governments could not lay claims to the open seas. Consequently, passage across it was free. The principle of international waters still valid in public international law is based on it. More than fifteen years later, in 1625, Grotius published De iure belli ac pacis (On the Law of War and Peace), a guideline that lawyers could use to categorize whether acts of war were lawful or not. In this way, Grotius’ legal thinking limited the absolute power of the state. In doing so, he became one of the founders of natural law, which conferred a set of inalienable rights on the individual.

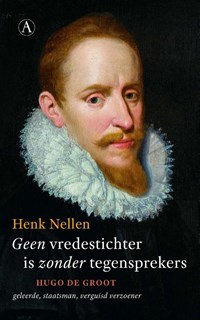

Portrait of Hugo Grotius by Michiel Jansz van Mierevelt (workshop of), 1631

Portrait of Hugo Grotius by Michiel Jansz van Mierevelt (workshop of), 1631@ Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The renewed interest in Grotius’ legal oeuvre in the decades around 1900 resulted in a veritable cult. In 1886, for example, a statue was erected to him in Grotius’ native city of Delft. Almost simultaneously, some of his descendants donated the chest of books in which he allegedly escaped from Loevestein Castle in 1621 to the then newly established Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Three copies of that chest are in circulation in as many museums, a clear sign that in the meantime it had taken on the features of a relic.

More than four hundred years later, the image of the peace-loving scholar who evaded an undeserved punishment thanks to an escape in his chest of books – about which more below – has lost none of its potency. That high-profile event was commemorated in 2021 with an exhibition in Loevestein Castle, a series of “Freedom Lectures” and even a special Hugo Grotius stamp. The new biography of Grotius by historian Henk Nellen also fits into this series of events.

In doing so Nellen is a seasoned observer. This scholar has devoted almost his entire working life to the edition of Grotius’ correspondence. He is more familiar with his oeuvre than any other researcher. In fact, relatively recently, in 2007, Nellen published an exhaustive biography of Grotius, which was subsequently translated into English. Yet the new book, half as thick, is by no means a rehash of the previous one. The most recent biography is less specialized. This time Nellen pays more attention than in his previous book to Grotius’ family life and to his circle of correspondents, both fervent admirers and rabid opponents. This immediately touches on the paradoxes of Grotius’s life story: although he is known as an early modern champion of tolerance and tried to bridge religious differences, he got caught up in conflicts remarkably often, which he subsequently fought out with a pen dipped in vitriol.

Tried and tested in humanistic culture, whether it be philology, history or theology, Grotius was constantly looking for the oldest and therefore the most reliable texts

As I mentioned above, nowadays Grotius is mainly known among jurists. But law was by no means the only field on which Grotius focused. Perhaps he himself, especially in his later years, attached more value to his activities as a theologian. But Grotius also made a name for himself as a philologist and historian. Moreover, he had been one of the leading policymakers of the Dutch Republic until his imprisonment in 1619. Less successful was his stint as Swedish ambassador to the French royal court during the last decade of his life. More so than in his earlier biography, Nellen gives full attention to Grotius’ versatility.

Tried and tested in humanistic culture, whether it be philology, history or theology, Grotius was constantly looking for the oldest and therefore the most reliable texts. But unlike such famous predecessors as Erasmus, Grotius realized that so many centuries had passed between the period of Classical Antiquity and early Christianity on the one hand and his own time on the other that the original texts could no longer be flawlessly reconstructed. That did not necessarily have to be a bad thing: by having recourse to the authors’ contemporaries, even if they were pagans, and a careful study of the context, God’s intentions and the truth could still be reconstructed. Grotius thus showed himself to be a transitional figure who, although he was deeply religious himself, heralded the secularization of our worldview.

The (presumed) chest of books in which Hugo de Groot escaped from Loevestein Castle.

The (presumed) chest of books in which Hugo de Groot escaped from Loevestein Castle.@ Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

All this may seem uncontroversial to us, but it certainly was in the first half of the seventeenth century. In fact, his religious and political positions had even endangered Grotius’s life during the first decades of his career. Together with his mentor and friend Johan van Oldenbarnevelt (1547-1619), Grotius had manifested himself as one of the leaders of the Remonstrants or “the moderates”. This movement within Calvinism mitigated the effects of divine predestination on human salvation and advocated a broad church. In that church, there was room for different convictions, but it was under the control of the local, often municipal rulers.

The Counter-Remonstrants or “strict ones”, on the other hand, interpreted Calvin’s doctrine of predestination in a strict way and opened membership of the church only to believers who wished to manifest themselves as “the salt of the earth”. In that view, the church was allowed to govern itself without too much supervision from city officials, who often did not even want to conform to its precepts. When tensions ran high between the two groups, Stadtholder Maurits van Oranje increasingly identified himself with the strict ones, and then seized power, imprisoned his opponents, and brought them before an extraordinary court.

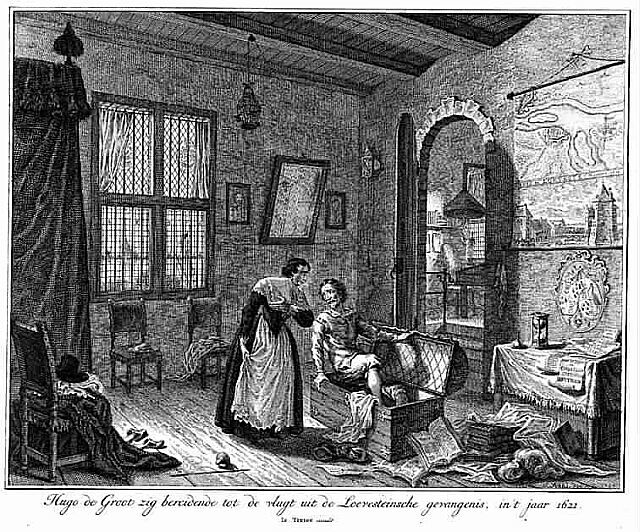

The spectacular escape from Loevestein, as pictured in an 18th-century engraving.

The spectacular escape from Loevestein, as pictured in an 18th-century engraving.© Wikipedia

Unlike Oldenbarnevelt, Grotius, who had something of a reclusive scholar, let himself be intimidated by his interrogators during the harsh interrogations that followed and during the trial, he behaved like a henpecked husband. Grotius was therefore not sentenced to death like Oldenbarnevelt. His sentence was life imprisonment in the Loevestein state prison. In the end, he would spend less than two years there. With the help of his wife, the brave Maria van Reigersberch, Grotius, as mentioned above, had himself carried outside on 22 March 1621 in the chest of books that had just brought a fresh batch of reading material to his cell. Arriving in nearby Gorinchem, where it was market day, Grotius dressed up as a bricklayer’s servant, blended in with the shoppers and then fled to Paris via Antwerp.

It was a spectacular story that captured the imagination and was passed on from generation to generation. Not only did Grotius fit in his chest of books, but figuratively speaking also all the republicans who opposed the concentration of power in the hands of the successive Princes of Orange and their clique during the time of the Dutch Republic. But it also made Grotius a somewhat one-dimensional hero.

The greatest achievement of Henk Nellen’s biography is his adding depth to the portrayal of who Grotius was

The greatest achievement of Henk Nellen’s biography is in adding depth to the portrayal of who Grotius was. Grotius’ conviction and escape formed a watershed in his life. Until then, practically everything this “child prodigy” put his hand to had been smooth sailing. But once he arrived in Paris, he also became a somewhat resentful man who neither forgot nor forgave the wrong he had suffered. Deprived of his regular income and wealth, at first Grotius had to economize in Paris. As a Swedish ambassador, he sometimes behaved very haughtily towards those who did not show him the respect he felt he was owed. Hugo set high standards for his three sons, which they were unable or unwilling to meet.

All this attention to Grotius’ versatile talents, to his being a spider in the web of correspondence of the Republic of Letters and to the details of his personal life, resulted in a beautiful portrait. Not only can the reader appreciate Grotius’ significance much better than before, but also gain an extremely fascinating glimpse into the functioning of the international academic world in the first half of the seventeenth century.

Henk Nellen, Geen vredestichter is zonder tegensprekers. Hugo de Groot, geleerde, staatsman, verguisd verzoener (No Peacemaker Is Without Contradictions. Hugo de Groot, scholar, statesman, reviled conciliator), Athenaeum, Amsterdam, 2021, 416 pages.