From catchy slogans at demonstrations to stand-up comedians’ biting wit and scorching one-liners in the political arena, humour is right there in the boxing ring of our society. So, there is much more to jokes and witticisms than just getting a laugh. But how does humour relate to power? And can today’s activists still laugh at themselves?

Did the tens of thousands of participants in the recent climate marches in the Netherlands and Belgium have zero feeling for humour? That would be a lie. There were fun slogans on banners, like I fall for men with a small… footprint, Fuck Each Other, Not The Planet, and The Climate Is Hotter Than My Boyfriend. There was also The Climate is Hotter Than Rutte, while in the crowd there was a doll representing the Dutch Prime Minister grilling the globe on a barbecue.

That said though, the hallmark of the climate movement is not its sense of humour. The young Swedish activist, Greta Thunberg, may have made a bold gesture with her placard Skolstrejk för Klimatet, but she still does not make the world smile. If Thunberg had a better sense of humour, some say, she would come over as nicer and have more impact.

© Mika Baumeister - Unsplash

But Thunberg is not the only one to be labelled “humourless”. In a noted column in the Belgian newspaper Het Belang van Limburg a few months ago,

radio presenter Anke Buckinx lashed out against the woke movement, the initially African American trend of denouncing every form of racism wherever it occurs. ‘Woke is actually a synonym for whiner’, wrote Buckinx, after which she was met with a storm of protest, as well as many expressions of support.

Buckinx’ fellow radio producer, Sven Ornelis, defended her. ‘Calm down a bit’, he wrote on his site, ‘don’t whine about everything, don’t label everyone who laughs at a stereotypical joke as racist.’

Often enough, the verdict is that climate activists, the woke movement and many devout believers, too, have absolutely no sense of humour, and therefore the devout, whether they are Christians, Jews or Muslims, cannot laugh at the cartoons in Charlie Hebdo.

We used to be able to laugh

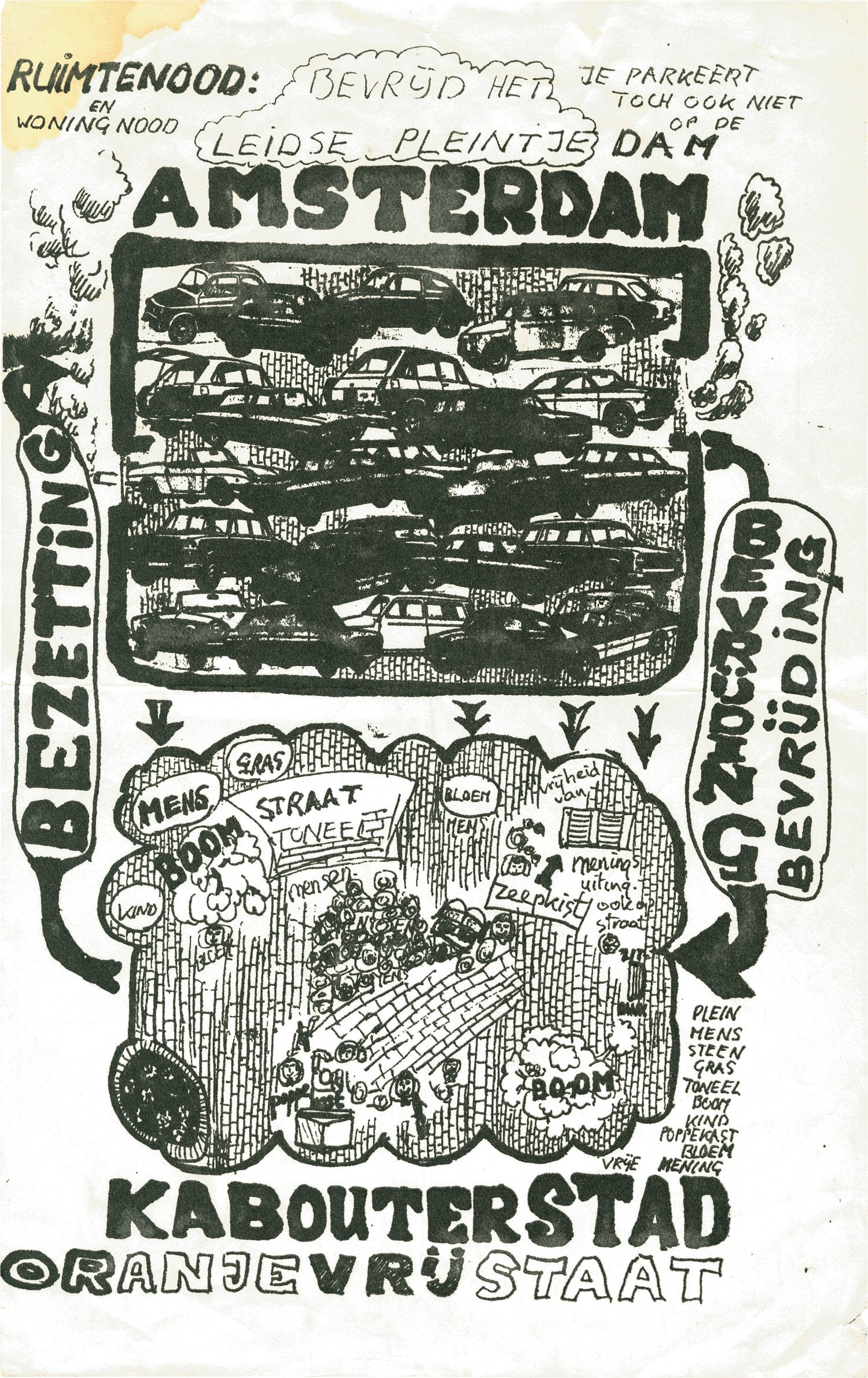

But can we – and are we still allowed to – have fun today? Do the defenders of the good cause still have a sense of self-mockery? Many citizens are tempted, like Buckinx, to say no. In other words, things used to be better. The Provos and squatters in Amsterdam in the 1960s and 1970s, the self-proclaimed “gnomes” (Kabouters) who handed out currants (krenten) in protest against officials’ stinginess (krenterigheid) and participated in local elections with the “Amsterdam gnome city” (Amsterdam-Kabouterstad) party, yes indeed, they knew how to laugh – at someone else of course, but at themselves too.

One of the ‘Gnomes’ protest posters in Amsterdam in the 1960s and 1970s

One of the ‘Gnomes’ protest posters in Amsterdam in the 1960s and 1970s© International Institute for Social History, Amsterdam

‘Their humour was more playful and inspired by Dadaism’, explains cultural sociologist and humour specialist Giselinde Kuipers (KU Leuven). ‘By calling themselves “gnomes” they added something childlike to their actions. You see less of that these days, humour has become harder and the jokes coarser.’

‘There is no less humour than there used to be, but there is a lot of tasteless humour’, agrees Antwerp-based gender activist, actor, stand-up comedian and creative Jack-of-all-trades Jaouad Alloul. ‘Not from the activists, but from their opponents. These are often older white men who find it difficult to abandon their ancient cracks about women, gays or other minorities, and feel targeted by people who are no longer prepared to swallow their humour.’

Alloul is struck by how well downbeat humour still does in Flanders. ‘Toilet humour, you might say, which is far from the more refined British humour of which I am a big fan.’

‘The norm, however, is shifting’, observes Dick Zijp, who is finishing a thesis on humour at the University of Utrecht and reviews cabaret performances for De Groene Amsterdammer. ‘Jokes about minorities are much less tolerated by the mainstream than they used to be. On the other hand, hard humour, with comedians who have become quite offensive, has evolved into a niche in itself.’

Zijp should know. In a column for the Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant, in summer 2021, he referred to a statement by the actress and director Ilse Warringa, who – a bit like Buckinx in Flanders – had complained that people constantly feel they are being attacked. ‘The moment you can’t put things in perspective with humour anymore, we’ll all stagnate’, Warringa had said in an interview. She had also added that minorities only belong if we’re allowed to make fun of them and they can laugh at themselves.

Zijp disagrees, ‘Very often the undertone is “give me the right to tell hard jokes about you”. That’s the liberal humour regime. It means that, if a joke is made about you, it is best to just laugh along with the rest.’ The term, as Zijp himself points out, was coined by Giselinde Kuipers.

Dick Zijp: 'It is downright absurd to expect disadvantaged groups to laugh along with the jokes you make about them'

Then humour is called inclusive, says Zijp. ‘In my column [which earned him the nickname ‘gender-neutral cunt head’ because of stand-up comedian Hans Teeuwen, LD] I wrote that that sort of humour denies the power relations in society. It is downright absurd to expect disadvantaged groups to laugh along with the jokes you make about them.’

Kuipers agrees with that, ‘A lot of humour comes from people who are socially secure and targets others with a relatively low status or in a vulnerable position. The jokers are usually unaware that you need a lot of social capital for self-mockery. If you call them on it, you quickly become a killjoy. Anyone who doesn’t conform to a particular sort of humour is considered boring.’

Giselinde Kuipers: 'Anyone who doesn’t conform to a particular sort of humour is considered boring'

But Jaouad Alloul will certainly not deny that self-mockery is still important. In his theatre production ‘The girl’ (De meisje, 2019-2020), a monologue about his self-acceptance, coming-out and complex relationship with his family, humour and self-deprecation are part of the story. ‘An activist has to understand that not everyone is equally knowledgeable about a particular issue and that non-activists must be able to follow as well’, says Alloul. ‘Yet not every activist should use humour or make themselves vulnerable to make others laugh. It’s too easy, from your own privileged lack of awareness, to blame people for not being able to laugh at themselves.’

Humour as lubricant

Activism and humour, they are still rather uncomfortable bedfellows. ‘Nonetheless, I do think that humour has a role to play now and then’, says Eva Rovers, author of ‘Practivism. A handbook for closeted rebels’

(NL only, Practivisme. Een handboek voor heimelijke rebellen, Prometheus, 2018). ‘Satire is certainly gladly used in the climate movement. Extinction Rebellion, Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth often employ humour, parody and self-mockery. I refer, in my book, to the Nanas against fracking, grandmothers who protest against shale gas drilling in Great Britain, taking to the streets as a cliché of themselves, with aprons and toilet brushes. You can really get a message across with clever humour.’

‘Humour’, agrees Alloul, ‘is an excellent lubricant for raising difficult themes and taboos, such as social injustice. Humour is a powerful way of expressing painful situations, the fact, for example, that while some live a gilded life, so many others are struggling. A funny angle can act as an eye opener and really serve a cause.’

Eva Rovers: 'Satire is gladly used in the climate movement'

‘Humour is also an important rhetorical tool’, adds Dick Zijp. ‘Take Zondag met Lubach [‘Sunday with Lubach’, a popular satirical programme on Dutch TV, from 2014 till March 2021, LD]. Research shows that their satire about right-wing nationalist politician Geert Wilders did have an effect, in the sense that after the broadcast people were less inclined to vote for his party, the PVV.’

Arjan Lubach, host of the popular satirical programme 'Zondag met Lubach'

Arjan Lubach, host of the popular satirical programme 'Zondag met Lubach'© VPRO

‘Arjen Lubach was a master at tackling every social wrong with humour’, confirms Rovers. ‘The greenwashing of Shell, for example. That’s another good example of how humour can get things onto the agenda.’

‘Humour is part of every activist’s toolbox’, stresses Giselinde Kuipers. ‘Jokes and mockery are important as tools to undermine power and change the world. Activism is less successful without humour, although you have to adapt it with an eye to groups and audiences. Humour is culture specific, and people can soon feel their individuality is being attacked.’

Funny billboards at climate marches. Giselinde Kuipers: ‘Humour is part of every activist’s toolbox’

Funny billboards at climate marches. Giselinde Kuipers: ‘Humour is part of every activist’s toolbox’© Unsplash

‘You have to be careful’, warns Alloul as well. ‘People can experience humour in very different ways. It’s often not good and therefore misses its target. Humour has to both confront and expose the blind spot and keep the intellect intact. That’s a difficult combination.’ ‘Humour should not make light of an issue to such an extent that it can be trivialized’, concludes Zijp.

Jaouad Alloul: 'Humour has to both confront and expose the blind spot and keep the intellect intact'

The latter is one of the messages that gender scientist Linda Duits conveys in her book ‘Crazy myths. A fresh fact check of feminism then and now’ (Dolle mythes. Een frisse factcheck van feminisme toen en nu, Amsterdam University Press, 2017) – its title, incidentally, is a humorous reference to the Dutch feminist movement Dolle Mina. The cliché would have it that feminists are “carping harpies” with no sense of humour, whereas, according to Duits, that was certainly not the case with the Dolle Mina. One of the actions that made the collective famous was its demand to be entitled to whistle at men. Likewise, the fact that the Dolle Mina was almost called ‘The gawked-at cunt’ (De Versierde Kut), referring to the way in which women often feel they are looked at by men, still makes people laugh.

In retrospect, though, was this humour effective, and did it not actually get in the way of the struggle for more women’s rights? Was it not precisely the humorous filter that caused the Dolle Mina to be put down as innocent and consumer-minded?

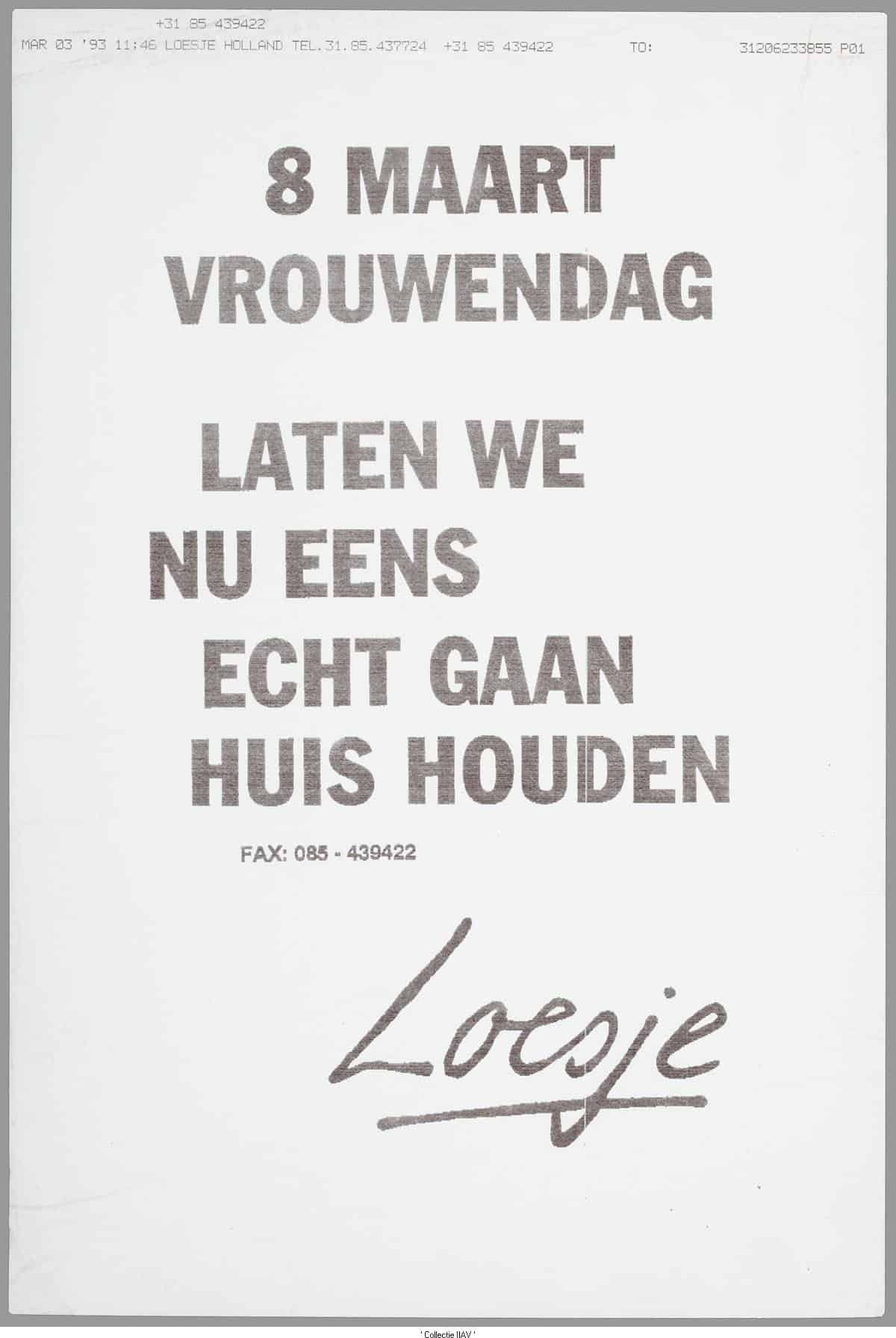

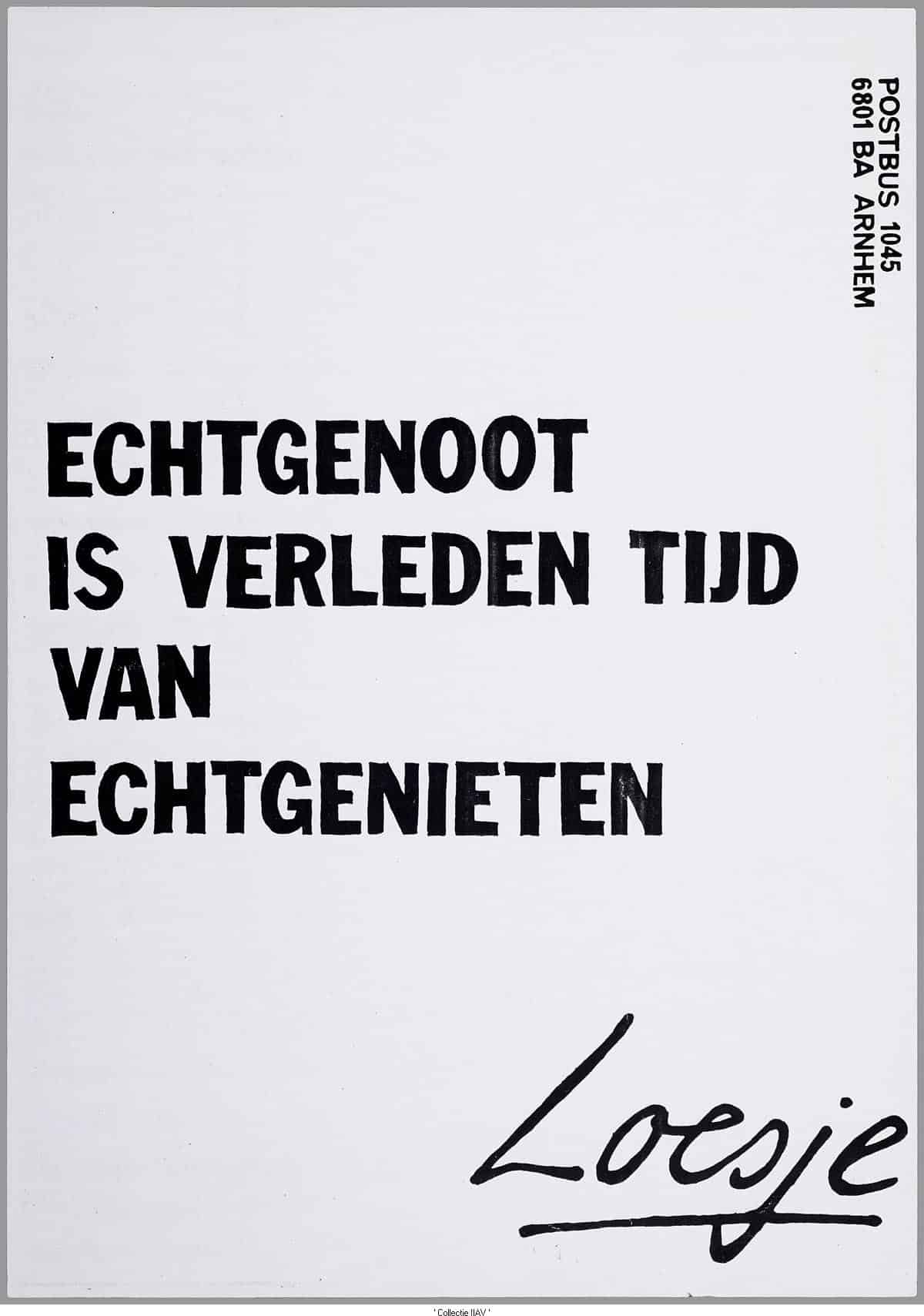

This innocence also applies to a certain extent to Loesje, thinks Eva Rovers. Loesje is the fictitious girl, invented in Arnhem, who hangs up funny and humanist slogans in public spaces. ‘Loesje is really nice, but she remains safely anonymous. What’s more, precisely because she is so nice, she doesn’t really have the calibre to change the world.’

Two posters with funny slogans by Loesje. Eva Rovers: 'Loesje is really nice, but she remains safely anonymous. What’s more, precisely because she is so nice, she doesn’t really have the calibre to change the world'

Two posters with funny slogans by Loesje. Eva Rovers: 'Loesje is really nice, but she remains safely anonymous. What’s more, precisely because she is so nice, she doesn’t really have the calibre to change the world'Everyone loves to laugh, but humour does not always work for everyone. And above all, some topics don’t lend themselves to it. ‘I suspect that the pain felt by many contemporary activists – in contrast to what was the case with the Provos and the Kabouters – is too great to be able to be very light-hearted about the issue they are fighting for’, continues Rovers. ‘They personally have something at stake. Whether it is racism, sexism, poverty or the climate.’

Jaouad Alloul: 'Families trying desperately to flee their country? It’s just better not to laugh at situations like these'

Or, as Jaouad Alloul puts it, ‘When it comes to a topic like famine, you can’t really joke. And families trying desperately to flee their country? It’s just better not to laugh at situations like these.’ So, activists will not achieve anything with humour alone, fears this Antwerp native. ‘Freedom is just as important, as are passion, awareness, empathy and indignation.’

Briefly dangerous

‘Humour is often romanticised’, points out Giselinde Kuipers. ‘But if you look at it empirically, you see that humour that makes power look foolish is rather more in the minority. Most humour perpetuates power. In essence, humour is neither for nor against those in power, but because it is slippery and ambiguous, it very often slips right back into the power groove. A joke is dangerous, but only briefly. It becomes embedded and the threat remains contained.’

Giselinde Kuipers: 'Humour that makes power look foolish is in the minority'

And yet, whether it is good or bad, contentious or not, fine or coarse, right or left-wing, humour is not only ubiquitous, it is also perceived as terribly important in modern society. According to Zijp, ‘We have even come to believe that a sense of humour is fundamental to making us good people, that it is precisely humour that makes us a good person. So, humour is strongly linked to morality and ideology.’

To such an extent even that people without humour are dismissed as bad, according to the cultural scientist. ‘You see that very clearly in politics. We find it difficult to laugh at the humour of political opponents, because that would imply that they were good people. Those who do not agree with the climate activists’ message will not be inclined to find their humour good. On the contrary.’

Humour is identity

‘Humour tells us a lot about the way our society is organised’, adds Kuipers, ‘and is specifically chosen as a battleground for settling conflicts. You can see that on social media too, the memes and so on; humour no longer works just as a side effect, but as a part of our identity.’

Kuipers reinforces her point in an article called ‘Anything goes for jesters’ (De nar mag alles), which she wrote for De Groene Amsterdammer two and a half years ago. In it she emphasises the extent to which ‘crude jokes, clownish wantonness and irrational behaviour have claimed their place at the centre of power’: the Italian right-wing populist politician Matteo Salvini comparing a female member of parliament to an inflatable doll (just kidding!); former US President Donald Trump mimicking a disabled journalist, ‘with strange movements and a crooked arm’, or British Prime Minister Boris Johnson who ‘constantly contradicts himself, insults and lies, but does it with so much humour and ‘charm’ that it only endears him to his voters.’

It is humour against humour, that of the populists against that of the activists, in this case

Their electorate thinks it is great, humour à la Salvini, Trump and Johnson. ‘In reality their antics intensify the us-and-them feeling’, writes Kuipers, ‘and polarise society.’ In other words, it is humour against humour. That of the populists against that of the activists, in this case.

Fortunately for the latter, humour serves not only to bring a message closer to a wider audience, it is also often enough psychological fuel for the activists themselves. Or, as a woman from Groningen who has absolutely had enough of the gas extraction in her province remarks in Rovers’ book Practivisme, ‘The only thing that keeps me going is rage. But you can’t keep that up forever. Rage consumes you!’

Get really angry, the author advises, but at least make sure you yourself still have fun with it.