In ‘Overal zit mens’ by Yves Petry, Revolt Is Imminent

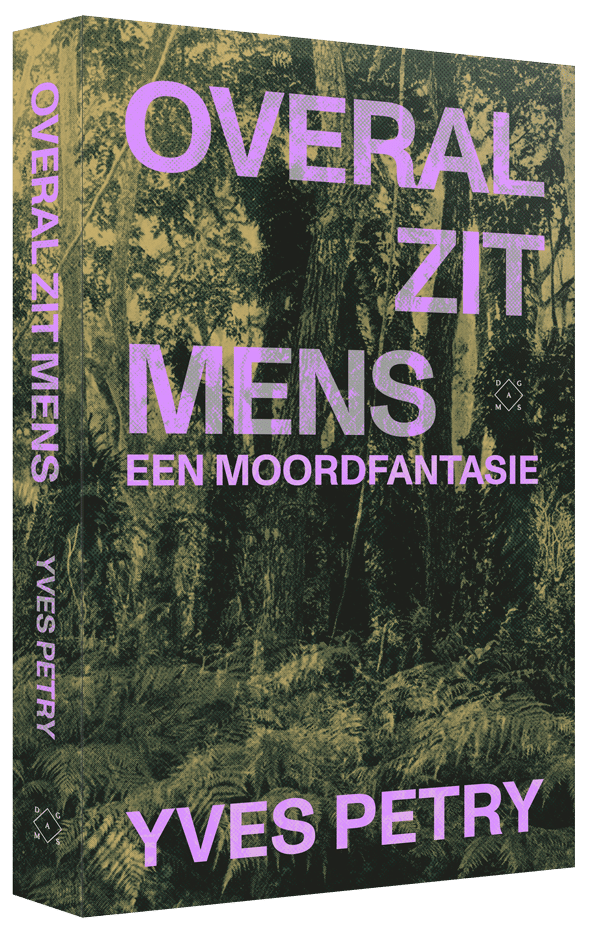

Is the protagonist of Yves Petry’s eighth novel, Overal zit mens (Man Is Everywhere), just a raving madman? Or does he have a point, with his philosophical and societal statements? Mainly mad, we are led to conclude.

Kasper Kind, almost 50, wants to commit a murder. And not a random one at that. The main character of Overal zit mens (Man Is Everywhere), the eighth novel by Yves Petry, intends to kill Max De Man – a journalist who has a major influence on public discourse with his opinion pieces, documentaries, and talk show appearances. But above all, this man, who is everywhere, reminds Kasper of a painful ordeal. De Man is both an ex-lover of his and also the father of his twin sister’s daughter.

Yves Petry

Yves Petry© Johan Jacobs

The novel, subtitled A murder fantasy, is divided into two parts. The first part, which represents the bulk of the text, is called ‘the fantasy.’ Here, Kasper explains who he wants to kill, why he is targeting this personification of everything that is wrong in society, how he will do it, and what he will say before delivering the fatal shot. This is all set against the background of his daily existence as caretaker of the Mirandel forest and an increasingly hostile quarrel by email with his sister.

Part two is called ‘the murder’. Does he actually carry out his plan? I prefer not to give this away. In part one it is made pretty plain that the other characters do not view him as he views himself, so we can reasonably assume that events might take a different course to the one Kasper foresees. While he considers himself to be the only rationally thinking person, other people know better. His employees, frightened of him, begin to avoid him. His niece even sounds the alarm after a visit.

Petry drops so many hints that you have to put Kasper’s thinking into perspective. As much as he may swear that his choice of target stems from purely philosophical considerations, you are forced to reason like his sister. She has built a successful career as an organisational psychologist and therefore interprets everything according to the psychological viewpoints on attachment, trauma, and comfort that you encounter everywhere today: from women’s magazines to high-brow media. She seeks her brother’s real motives in his own personal traumas.

Do theories about the oppressed individual in today’s mass society justify the murder of someone else?

There are quite a few. He lost both his parents when he was seventeen in a freak hot air balloon accident. Before that, it is suggested, he had received a strict upbringing, aimed at becoming a model citizen. He suffers from Asperger’s syndrome, it transpires, which means that he a) has trouble interacting with other people, and b) single-mindedly devotes himself to a particular interest. And this happens to be forest management, or nature, broadly speaking. In other words: a passion that is marked by climate change and therefore sorrow at its destruction.

And then there’s that intimate relationship with the intended victim. It had only lasted a year when Kasper – who had until then desired women – was in his mid-twenties. And it was over in an instant when Max helped his sister conceive a child. There was a fierce row, in which Max said that their relationship had really just been to help Kasper accept himself. How do you mean, love? An intense fight followed. And then they never saw each other again.

Yet, Overal zit mens (Man Is Everywhere) is about more than getting to know and interpreting Kasper’s personality. Just like in De maagd Marino (The Virgin Marino, 2010) – which received the Libris Literature Prize – Petry forces the reader to engage with people you instinctively keep at arm’s length. Simply by letting them speak for a long time. In his most successful novel to date, such characters were the cannibal and the man who lets himself be killed and eaten. What possessed them? And above all: is there any reason or even understanding to be found in their motives?

Petry’s latest novel deals with Kasper’s theories about the oppressed individual in today’s mass society. Do they somehow justify the murder of someone else – in this case, a man who, as a well-known Fleming, more than anything symbolises what has gone wrong in contemporary society? In other words: the conformity of being woke (although that word is not mentioned) and the right attitude in life to ‘being yourself’. And also the boundless vanity, the thirst for success, the need for attention.

With his crystal-clear style Petry makes a sermon resound like a thunderous bell

Unfortunately, this is not the strongest point of the book. Firstly, because Kasper’s madness gets in the way of his philosophies. Where the twisted characters in The Virgin Marino helped foster understanding for their eccentric act, the effect is reversed in this book. As you read, the more you realise how unreliable the narrator is, and the less you are inclined to take him seriously. How do you mean criticism of society? What right to kill? You need help!

This is reinforced by the philosophies themselves, which are pretty sparse. Kasper repeatedly tries to put them into words. Sometimes in misanthropic tirades to himself, sometimes in his mind to Max, when he pictures himself standing at his door with a loaded gun and delivering his closing speech. But actually, he never gets beyond some flimsy slogans that man also has the right to be bad – slogans, moreover, that are always crowded out by the stream of insults directed at Max.

“Don’t think that I’m just an isolated madman,” he rants, for example. “I too have millions on my side. Oh, didn’t you know? Then you know now. The revolt of individuals is imminent, Max. The revolt of people like me, who are sick and tired of your social moralising and snooty media chat, who are horrified by a future in which they should become increasingly transparent, open, characterless, more general and more humane. We do not intend to turn into the tame sponges you want us to be.”

And that in the middle of a four-page tirade. The best you can say about it is that Petry writes it beautifully. With his crystal-clear style, which in my mind evokes associations with a sunny, windless day in nature at five degrees below zero, he makes the sermon resound like a thunderous bell. Like the opposite of Tom Lanoye’s baroque flourishes, but with the same rich language. But will Kasper convince you? Not for a second. Then he really needs to come up with arguments instead of taunts.

It is interesting to wonder what Petry intends by this. He has gotten so deep into his main character that you suspect he shares Kasper’s aversion to emotion-driven spectacle culture. That’s how sincere Kasper sounds. But if I accept that assumption, I must also admit that an intelligent writer should come up with a better justification for murder. I prefer to think the opposite, therefore. That via Kasper Petry tries to ridicule the anti-woke activist.

Yves Petry, Overal zit mens, Das Mag, Amsterdam, 2022, 250 pages

Excerpt of ‘Overal zit mens’, translated by Laura Vroomen

‘We cannot act without moving towards a phantom.’ Paul Valéry

1. Fantasy

Man is everywhere. The human element has nestled in every corner of this earthly domain, in every pore of the biosphere. We breathe man, we eat man, we drink man. There’s no bit of moss, no drop from the ocean, no sample of soil or permanent snow that doesn’t contain millions of human molecules. In fact, permanent is no longer a useful term. Everything has become man, that’s to say, everything is tainted, everything is adrift. There’s no escape. Those who long for panoramas that are unspoilt or life cycles that are uncorrupted by the human factor will have to go to the moon – and beyond even, just to be on the safe side. Prophets of doom don’t have to bend over backwards anymore. We all get the message. Many of us feel more depressed by the possibility of a planetary catastrophe than by the inevitability of our own death. Ten-year-old children are as doom-conscious as consummate climatologists. The apocalypse has become a cliché before it’s even come to pass. Every day, we’re bombarded with terrifying figures and reports. Every day, we’re confronted with our own filth. Whether that makes us clean up our act remains to be seen. But many are those – and their numbers are increasing – who are left with an intense disgust and who barely manage to hide their aversion to the human enterprise. For not a few of us, the Anthropocene seems to also herald the arrival of the Misanthropocene. Like methane that’s released from the melting tundra, the crush of humanity gives off an air of misanthropy. Out of habit, most people will want to take their hatred out on their fellow man, not on themselves. But unlike in the past we won’t be able to attribute this hatred to the differences between us. What do they even mean in light of what’s to come? We will hate the others even though there’s no longer any distinction to speak of between us and them, even though they are going through the same trials and tribulations and the same fears as us. We will hate the others despite – and also because of – the fact that we will see ourselves and our panic reflected by them. Because they block our way out and we theirs. We will hate one another, even though we have become indistinguishable like skeletons, like X-rays in the eyes of a layperson. We will certainly recognise the equal, the fellow sufferer and the kindred spirit in our neighbour, but that won’t be a reason to love him or her, far from it. Let’s face it, there are way too many of us. Nobody will be first, everybody will be last. No chosen few, all will be damned. No more men and women, no more races and distinct cultures, no more imaginary identities and self-declared minorities. Only stripped bare, identical human animals with no direction.

Sapiens is going nowhere.

He is everywhere.

As you can tell, I’m taking the situation extremely seriously. I’m aware of the burden my contemporaries are carrying and in no way underestimate their general sense of malaise and despair. Perhaps I’m even exaggerating ever so slightly, and their mental wellbeing is actually not that bad. I personally don’t feel completely devasted yet by the figures of doom and the statistics of disaster. In fact, at times they even inspire a certain playfulness in me. I try to think of provocative words to express the worst, express the worst and derive an unmistakable pleasure from it. It’s a tad perverse of me, I admit that. You might have expected a greater sense of responsibility from someone approaching fifty. But that’s just how it is. Even so, to look at me you’d never think I was flippant. I’m not singing and strumming my harp like some Nero figure, enjoying myself while the world burns. For the time being I’m keeping a low profile, sharing my thoughts with no one. With no one but you. You don’t exist, but that’s not a problem. It would be premature to address an actual audience at this stage of my plan.

What plan, I bet you want to know now.

Patience, my dear. We’ll come to that.

In due course.

*

Every time I visualise my final meeting with Max, in the ramblings of my mind that is, I picture a sunny day. That said, it shouldn’t be too warm, so it doesn’t look weird if I wear a coat that’s loose-fitting enough to conceal the contours of my service weapon – not a convenient little handgun but a rather hefty affair. A cool but bright day in October or November, let’s say. I board a train that takes me to the city where our Man lives, disembark on arrival and walk to his street, which isn’t far from the station. Up until this point, the sequence of events is easy to imagine. But what happens next raises a few practical questions that I’ll have to give some thought. How, for example, can I be certain that he’ll be at home that day? Or what if it’s not him who answers the door, but his bearded and bewhiskered buddy? In that case, I’ll have to get our Man to come to the door under some kind of pretext. Do I give my name, or should I use an alias? And what if I’m kindly invited to wait for him in the hallway? I’ll have to have a plausible excuse at the ready to turn this down. It would be better, I think, to carry out the assassination with the door open, to give it the character of a public act more than a private drama. Thorny questions. I don’t like lying. You only live once, which is really not a lot, so why lie your way through that singular life? Lies are rarely original. Those who lie are nearly all cut from the same cloth. Even if we’re not dealing with serious crimes against the truth here, but with a few tactical white lies at most, I dread doing even that. Suddenly I remember Hope. What if she’s there when Max and I come face to face? Might she not sense something before her owner catches on? Canines have their own radar. What if she starts growling or won’t stop barking at me, or who knows, even launches into a pre-emptive attack? It’s not as if I can gun down that utterly innocent creature!

Right, let’s just assume that it’s Max who comes to the door, all by himself, without a dog close by.

I can’t rule out that he won’t be able to place me straightaway. After all, we haven’t seen each other for over twenty years. Throughout his career as a journalist, as a top interviewer for various media outlets and as an in-demand guest on TV and radio talk shows, our Man has seen so many faces. But the instant I mention my name, he’ll freeze. A brief but powerful shockwave that’s palpable beyond his ears will wipe the routine goodwill from his face. A vague look of suspicion and loathing will take its place. Kasper Kidd on his doorstep, that doesn’t bode well, he’ll think, and he’ll be absolutely right. I take the pistol from my inside pocket. And here comes the truly challenging part. I don’t want to gun him down like he’s some kind of dumb animal. He ought to be aware, at least to some degree, why he deserves this bullet. But I won’t have much time to explain. As soon as he realises what’s coming to him, he’ll try to slam the door shut, and even if I manage to stop that, I’ll have to give chase through the hallway, perhaps even up flights of stairs, across rooms, and so on and so forth. Out of the question. I know how to handle a gun, but I’m not an experienced marksman. Nor can I take it as a given that I’ll be calm and collected enough to fire ten times before hitting my target. No, it will have to happen on the doorstep, in one, maximum two shots at close range. Perhaps I’d better speak first and pull the gun second. Even then, I fear that he won’t give me much time. My message will have to be very concise, no more than, say, two to three hundred words. Easier said than done. Like having less than a minute to try to sell something particularly unsellable to a particularly unwilling buyer. To be honest, that brief moment often worries me more than what will follow. During the police interrogation and over the course of my trial I’ll have plenty of opportunity to justify myself. Similarly, there’ll be time enough in prison for correspondence with likeminded individuals. But what do I tell Max himself?

Hopefully, I’ll have more clarity on that later.

Why Max De Man? I’ve entertained the idea of gunning down another intellectual swindler or another moralistic good-for-nothing. I’m spoilt for choice. And there are definite advantages to picking a target with whom I don’t share a past. Might my motives then not seem more principled, more pure, and therefore also more respectable in the eyes of some? Probably. On the other hand, I don’t want to pass myself off as an instrument of pure principle. It would be hypocritical. This is not a political act and I don’t want to pretend it is either. I don’t care about society, and society doesn’t care about me. Respectability? My arse! I’m acting alone, as I-am-who-I-am, driven by motives that take precedence over the rules of self-marketing and personal branding, and that’s why ultimately there can, must and will be no target other than Max De Man. It’s him I hate from the bottom of my heart; the others I merely dislike. I feel personally besmirched, trampled on and misunderstood by what Max says; merely repulsed by what the others say, even if they often use the exact same phrases. When I hear or read the others I shake my head with jaded abhorrence, but when I hear or read Max my blood boils with murderous urges no other man can rouse in me. It’s like infatuation: you have little choice in the matter. In fact, I ought to be grateful to Max for having a sworn enemy in him. Because if it weren’t for him, my antipathy to this era and to this humanity might generate little more than some toothless grumbling in the margins – as is true for so many among us. Whereas now I’ll be giving the performance of a lifetime and I’ll be killing it. Literally! Trust me, dear people, there’s nothing better than your own personal purpose in life. What a relief it will be to finally drive a hard leaden stake into that treacherous, porous, fake heart of his…

Keep burning, my hatred.

Unfortunately, I can’t show you a photo of our Man from the time when we hung out together. No doubt, such images exist, but I never took any myself and he never shared one with me. Take it from me that even in his twenties, he enhanced his physical appearance with the help of a carefully selected wardrobe. Aside from a small allowance, he had no income – he was, in his own words, a writer in the making who wanted to fully concentrate on honing his art – yet he was never short on money for clothes, despite claiming to have fallen out with his well-to-do parents. I often ridiculed him for his need to stand out and look like an interesting person, but I also envied him his talent for this. Wherever Max appeared, he rarely went unnoticed. Was I in love with him? That question may well be put to me later. Certainly not, I’ll answer, in the way that I’d fallen for girls in the past. That had been a matter of glands more than of words. Whether me and the girl in question had anything to talk about played a minor part in my imagination. As far as I was concerned, she didn’t even have to be awake. If some servile demon had dropped off her warm, yielding, pliable body in a state of unconsciousness, I’d have accepted it without a second thought as the most delightful gift imaginable. If only my sexual predilections had remained this primitive, I’ve thought on occasion. But they changed. I began to desire – not so much better or more exciting sex but sex for better or more exciting reasons. I believed that two young men who did it together undoubtedly had such reasons. If they didn’t know what these were, it was crucial to find out. An unconscious Max would have been of little use to me. I wanted him to be animated in a specific way, and for a while he somehow managed to make me believe that he was.

How come?

That question is as difficult to answer for me today as it was back then.

One evening, when Max and I had only known each other for a few weeks, and I was aware of his literary ambitions but hadn’t yet read any of his work, I was waiting alone in his room for him to come back from the bathroom. On his desk sat an enormous typewriter, a robust antique contraption fitted with big, round keys, which looked like a cross between a miniature factory and a safe. It had belonged to his grandfather, I knew, and even though it looked more like a museum piece than a functional device, the nearly 1-metre-long carriage contained a piece of paper. On it, as I could see from my chair, were a few typed paragraphs. I saw no reason to curb my curiosity and walked over to the desk. Just a few sentences in, I was knocked sideways by what I read. The highly sensitive prose, the emotional bravery, the conviction and the originality of his self-reflections: my friend turned out to be no less than an introspective genius! The uncompromising sincerity with which he voiced his sense of alienation and proclaimed it to be the foundation of every true life and of all true art – I could never have written so incisively, so magnificently about this topic, however close to my heart it was. I carefully read them through a second time, each of his bold meditations. It was all there on the page, there was no denying it, and yet I could scarcely believe my eyes. I returned to my chair, as heavy as a sandbag, internally crushed by Max’s superiority, not knowing whether to abhor or admire him. Of course, I wanted a gifted soulmate as a friend, but the fact that he was so much more brilliant than me bordered on unbearable. Nonetheless, in all honesty I had to admit, difficult though it was, that we were looking at an exceptional talent here, driven by a grandiose vision, a clearly articulated poetics, an inspired mission. What did I amount to compared to someone like that? No more than a barnacle clamped onto the body of a whale. Why did someone like that hang out with me? What could I offer him? I felt dizzy, as though I’d just been slapped in the face, and it was quite a struggle to hide my turmoil when Max re-entered the room.

At some point I said to him, quasi-casually, that I hoped he didn’t mind me taking the liberty of glancing at his work. He shrugged. He only did those kinds of things when he was stuck, he said.

It’s not bad actually, I said in a half-choked voice, because even though I’d broached the subject myself, and couldn’t possibly not have done so, I still had the greatest trouble getting the words out of my mouth.

Oh, you think that’s mine, he smiled sadly. Now I understand that look on your face. Thank you, but alas, it’s by Rilke. Rainer Maria Rilke. The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, you know it? You should read it. It’s right up your street. Sometimes I hope that by typing up a text like that, word for word, letter for letter, my fingers will loosen something in my head. Ridiculous, I know, but what can you do? I’m as stuck as a fly on a strip of flypaper!

© Yves Petry/Laura Vroomen/Das Mag/Flanders Literature