In the Footsteps of Albrecht Dürer: World Famous Painter Passing through the Low Countries

Five hundred years ago, Albrecht Dürer travelled through the Low Countries. This journey united everything that gave importance to the versatile European artist, from his artistic qualities to his status as a superstar. Dürer’s journey is now coming to life in all its fullness in an exhibition, several books and his own diary entries. ‘In my whole life, I have never seen anything that rejoiced my heart as much as these things.’

On August 2, 1520, Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) arrived in Antorf, as Antwerp was called by the Germans in the sixteenth century. The city on the Scheldt would become his new home for the next year for an extensive exploration of the Low Countries.

Self-Portrait, 1500, oil on canvas

Self-Portrait, 1500, oil on canvas© Alte Pinakothek, München

Dürer had left Nuremberg two weeks earlier with his wife Agnes and their servant Suzanne. On the Pegnitz River, central to Europe, that city lay at the crossroads of water and trade routes, halfway between Italy and the Netherlands, where the Renaissance flourished. The city maintained a liberal regime toward merchants, artisans, and artists, which made it the focus point attraction for intellect and craftsmanship, such as goldsmith Albrecht Dürer the Elder, Albrecht’s father who had immigrated from Hungary (his official family name was Ajtósi). The godfather of son Albrecht was Anton Koberger, publisher of the first book that described the history of the entire world: the Liber Chronicarum (Book of Chronicles). In the work, also known as the Nürnberger Weltchronik, the authors brought together the entire history of humanity, the Earth, and everything else that lived on earth.

When Dürer left for Antwerp, he was forty-nine years old and at the height of his career, after earlier trips through Italy where he had learned much about anatomy, perspective, and other insights from art and science.

When Dürer left for Antwerp, he was forty-nine years old and at the height of his career

His trip to the Low Countries was not only motivated by artistic inspirations. It was initially a business trip. In 1519 the Austrian emperor Maximilian I had died. He was a great fan and sponsor of Dürer: the emperor gave him an annual income of one hundred guilders. Emperor Charles V succeeded Maximilian. Dürer wanted to convince him to continue the endowment and would lobby Margaret of Austria, the governess of the Netherlands and aunt of the new emperor, with residence in Mechelen, to do so. In between, he would attend the coronation of Charles as the emperor in Aachen.

Dürer’s journey provides a powerful narrative in which all facets of his artistic practice, his artistic ambitions, his contacts with colleagues and high officials, and his attitude toward the Reformation come together. Thanks to his detailed travel diary, we know where and when he spent time and what he did and experienced there. The diary awaits a reprint in Dutch (the most recent dates back to 2014 and is only available at antiquarian bookshops), but in the meantime we must make do with a release from 1840 that can easily be found on the Internet.

In the summer and fall of 2021, the travelogue prompted an impressive exhibition at the Suermondt-Ludwig Museum in Aachen, and in November 2021, it will move to London’s National Gallery where it will be on display until the end of February 2022 (with a broader perspective also including Dürer’s other travels). The exhibition shows what a superstar Dürer already was in his own time. His signature, the large A with a D under its legs, was a strong trademark, similar to a modern logo.

Accountancy

Dürer’s travel diary is, surprisingly for a creative visual genius, mainly a household book in which he meticulously records expenses and income: eleven guilders a month for a room, bedroom, and bedding; every meal, with drinks, two pennies; ten pennies for the confessor; the price of coconuts, slippers, crucibles, stockings and a parrot basket (he regularly bought and was gifted a parrot); the drinking money for a servant, etc. It is also a register of which paintings, etchings, sketches or drawings he gives to people.

Dürer brought a suitcase full of his own work, which he generously handed out whenever he was invited somewhere. It was calculated generosity; the artist hoped to receive courtesies or commissions in return. That didn’t always work. Margaret of Austria did successfully lobby her cousin Charles V to perpetuate Dürer’s allowance, but nothing more. There was no commission for a new monumental altarpiece. That was a setback for him.

Dürer brought a suitcase full of his own work, which he generously handed out whenever he was invited somewhere

The regent’s rejection was not an artistic decision, but a political one. As a staunch Catholic, she could not afford to support a Protestant artist. It was a miracle already that the strict Catholic Emperor Charles continued to financially support the German painter. This is probably the reason why the overall balance was negative for Dürer, because “I have had no luck in the Netherlands with the things I created, consumed, sold, and other acts. Lady Margaret in particular, has not given me anything for what I have given her and made for her.”

From an art historical perspective, Dürer’s trip was a great success though. He painted only about twenty paintings that year, but drew drawings at a rapid pace. From his diary, you can tell that he produced more than a hundred portraits, some painted on wooden panels.

Dog resting, 1520, silver point on pale pink prepared paper

Dog resting, 1520, silver point on pale pink prepared paper© The British Museum, London

Striking is the rich series of one hundred and twenty drawings with pen, charcoal, brush, chalk and silver pen: buildings, landscapes, people, cityscapes and animals, many dogs but also exotic creatures such as lions and walruses. The harbor view of Antwerp is remarkable because of the space the artist leaves. He is also fascinated by fabrics and fashion, a sketch of a cloak is almost an abstract, contemporary geometric design.

Portrait of 20-year-old Katharina

Portrait of 20-year-old Katharina© Gallerie degli Uffizi, Firenze

His warm, human portraits show his exceptional powers of observation captured in fine detail – look at the portrait of the young Katharina, perhaps the first black woman in Western art history. She worked as a servant in the Casa de Portugal, the home of the Portuguese merchants. Her delicate features are caressed by the silver pen. (He drew with a silver pen on specially prepared paper; every mistake was visible and irreparable).

He spent most of his journey in Antwerp, the prosperous metropolis and art city, where he indulged in countless interesting encounters with artists, travelers, court officials, merchants (he was a close relative of the Fugger family of merchants), scholars and philosophers (Erasmus joined him). He stayed close to the Church of Our Lady in the Engelenborch Inn, where Joost Plankfelt provided rooms with a studio and cooking facilities. Dürer painted portraits of innkeepers and visitors several times, probably to settle some of his accounts.

From Antwerp he visited Aachen (where he attended the coronation of the new emperor), Nijmegen, Den Bosch, Mechelen, Ghent, Bruges and Brussels. He admired the Aztec treasure in the Coudenberg Palace, which was stolen by Hernán Cortés from Mexico: “Rarities from the new Gold Country. In all my life, I have never seen anything that has lift my heart as these things. I have seen wondrous things in them and marveled at the shrewd ingenuity of men in foreign lands.”

Curious

The artist’s journey takes place against a tumultuous background. Some of the great turning points in European history took place in those years: Luther published his theses against the Catholic Church, the exploration and exploitation of Africa and America was growing rapidly, and there was an influx of unseen animals, plants, and objects, while information spread faster than ever thanks to the printing press. In addition to the printed texts and prints, the plague rushed through the continent, fueling apocalyptic thoughts that the world was about to end.

There was not yet a market for autonomous drawings, but Dürer created his own niche

Dürer used these developments as a source of inspiration for his work and as a platform for his success. This was a bold marketing strategy for the time, as there was not yet a market for autonomous drawings, but this great master created his own niche that was subsequently filled by others, such as Lucas van Leyden and Barthel Bruyn. Dürer was one of the first to make good money without having to work on behalf of wealthy merchants, bishops or monarchs. His woodcuts and engravings made it possible to make many copies. His mother and his wife sold his prints on the market.

Meanwhile this work was not without consequences. In those days, art had a religious connotation. The better an artist depicted reality, the more heavenly his work was and the closer he was to God. Thus, Dürer’s work is the fabrication of the zeitgeist of the sixteenth century. He depicted nature so well (look at the hairs of the hare or the leaves of the tuft of grass) that he caught the soul of animals and plants on paper, showing what divinity meant to him and his contemporaries.

The Painter and the Whale

At a certain point, Dürer finds out that a whale, that wonderful mythical monster from the sea, has washed up on the beach of Walcheren. After he has seen Jan Gossaert’s altarpiece in Middelburg, he wants to see the stranded whale. In Arnemuiden, the ship’s mooring line breaks due to the strong wind and they drift off in a storm. They could only just be saved. Upon arrival, the whale turns out to have been washed away. Dürer contracts malaria (which was common in Zeeland at the time) and would suffer from recurring fever attacks for the rest of his life.

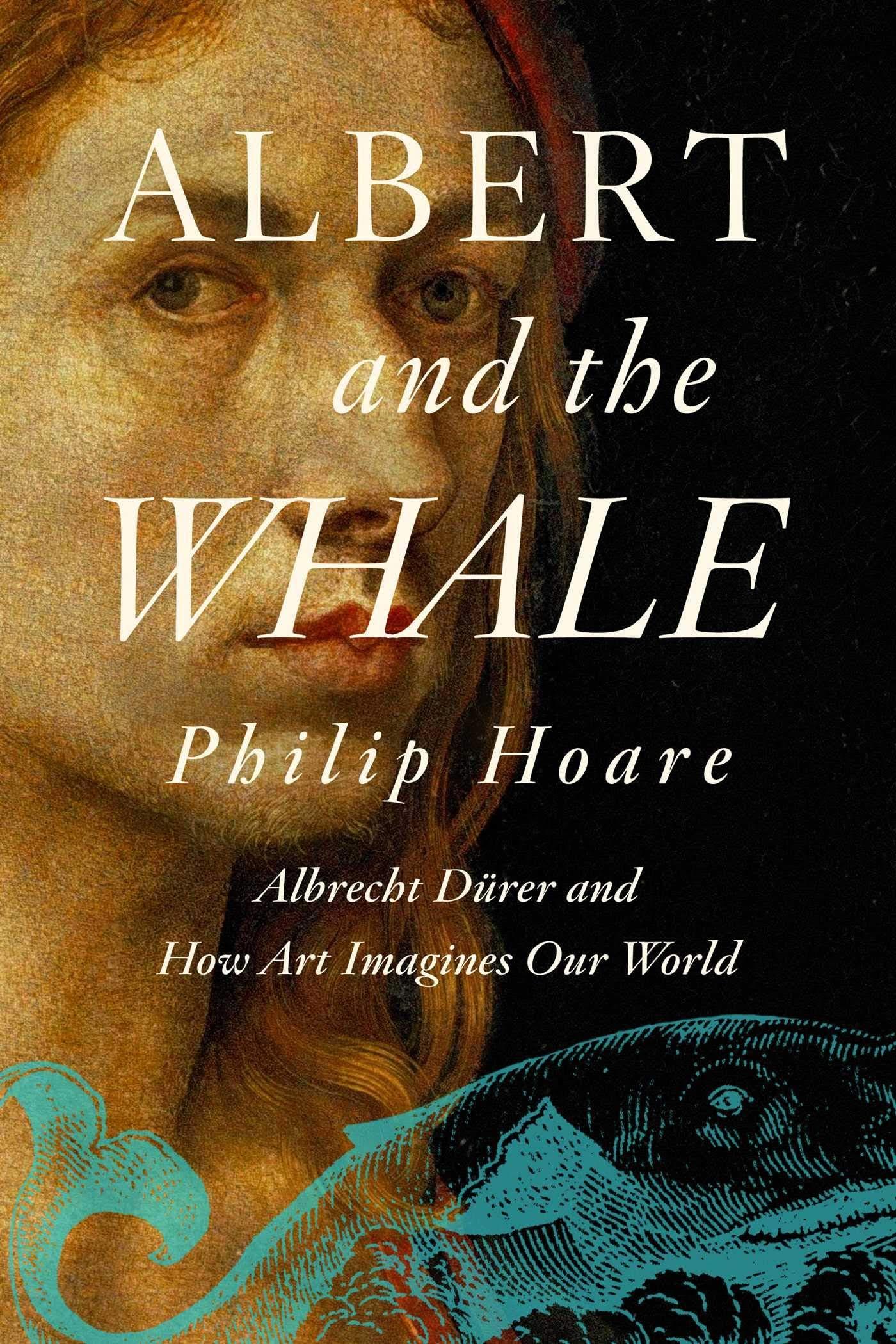

The short passage on Walcheren in Dürer’s travelogue prompted British author Philip Hoare to create a travelogue through time and space in search of the graphic genius and fascinating life of Dürer. In Albert and the Whale (2021), he reconstructs the life of the quirky artist in a memoir by using components from lives and artworks from later times. Like a new W. G. Sebald, Hoare portrays this by wandering through the lives of Thomas Mann, Marianne Moore, Charles Baudelaire, Herman Melville or David Bowie; blending memoirs, descriptions of nature, historiography and art criticism.

At the same time, it is an ode to the largest mammal on earth that we nearly drove to extinction and a praise to curiosity and research-driven art of the man who drew a rhino without ever having seen one in real life. What images can you create based on a verbal description? What words can you use to describe images? Those kinds of questions lead the reader through the labyrinth of voices and perspectives. It becomes almost physically tangible how Dürer looked at animals, like a monk reads scripture or an astronomer studies the stars. Taking a historical perspective, you start to look at old and new views with fresh eyes, steeped in empathy for animals and humans.

The port of Antwerp with the Scheldepoort, August 1520

The port of Antwerp with the Scheldepoort, August 1520© Albertina, Vienna

When Dürer stayed in the Low Countries, he was at the peak of his artistic mastery. It was no coincidence that he decided Antwerp would be his home at the time. In the city that was known to be an international hub of knowledge, art and commerce, he fed his curiosity and creativity. The city on the river Scheldt was an ideal breeding ground for his shrewd commercial spirit. He drew, painted, bought and sold, and built up his network of powerful and art-loving citizens. He was one of the few who could afford to buy the desirable blue of lapis lazuli, mined in Afghanistan. His work and notes testify to the interconnectedness of an individual artist to the glory years of a metropolis and its backlands.

Exhibitions

- Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist, 20 November 2021 – 27 February 2022, National Gallery, London.

- Dürer was hier. Een reis wordt een legende, 20 July 2021 – 24 October 2021, Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum, Aken.

Books

- Till-Holger Borchert en Peter van den Brink, Dürer was hier. Een reis wordt een legende, Ludion, Antwerp, 2021, 224 p.

- Philip Hoare, Albert & the whale. Albrecht Dürer and How Art Imagines Our World, Pegasus Books, New York, 2021, 304 p.

- Albrecht Dürer, Reis naar de Nederlanden 1520/21, Hoogland & Van Klaveren, Hoorn, 2014, 144 p.

- Albert Durer’s Dagverhaal zijner Nederlandsche reize in de jaren 1520 en 1521; de belangrijkste aantekeningen opgehelderd, Van Stockum, ’s Gravenhage, 1840. Available through Google Books.

- Michael Pye, Antwerpen. De gloriejaren.

De Bezige Bij, Amsterdam, 2021