In The Uncomfortable Documentary ‘White Balls On Walls’, The Stedelijk Museum Looks In The Mirror

In White Balls on Walls Sarah Vos follows how under new directorship, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam is wrestling with a more diverse and inclusive trajectory for its collections and staff. ‘The national character often reveals itself subconsciously in meetings’, says Vos about her deliciously uncomfortable documentary.

In 1995, the action group Gorilla Girls, which denounces sexism and racism in the art and culture world, ascended the steps of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam to protest against the museum’s ninety-nine percent American white male perspective. Their signs read Apartheid Art Show and White Balls on Walls. At the time, the Stedelijk didn’t have a single piece of work by an artist of colour in its collection, and only one percent of works had been created by women.

When a quarter of a century later, the new white, male director Rein Wolfs says he wants to change this state of affairs, the documentary filmmaker Sarah Vos decides to “be there” while it happens. Ninety percent of the art at the Stedelijk is still produced by white men, 6 percent is made by men of colour, and 4 percent is by women.

In her documentary White Balls on Walls, Sarah Vos (1968) witnesses how the uncomfortable inclusivity debate is brought into and conducted within the walls of the Stedelijk Museum. It provides an entertaining, cringe-inducing account of how the snow-white, elitist art world struggles with a social debate that seems a world away from its comfortable home. How do we find the right words to talk about it? What would be a better balance? And who stands to lose out as a result of this reclassification?

Uncomfortable self-reflection

The hermetic, smoothly polished bathtub with its tiny peephole to the outside world seems to epitomise the inward gaze. When the Surinamese-born artist Remy Jungerman tells us before his solo exhibition how he was once horrified to be asked to perform a ritual herbal bath, Wolfs quickly reacts that “that sort of thing is now a thing of the past”. But watching Vos’ documentary, you wonder how on earth it is possible that yet another audience is sitting bored, watching another group of musicians dressed in traditional clothing perform a Winti ritual at the opening.

It’s uncomfortable to watch an organisation looking at itself in the mirror attempting to investigate itself, without necessarily knowing what to look for. It’s delicious, to be shown the humanity behind the smooth design of the façade, and the individual ineptitude that seeps through the immaculate, functional whole. We see flawed good intentions, and hear how Charl Landvreugd – the organisation’s first black managerial staff member – thinks that “everyone here is very nice.” Behind that remark is a hidden world, the size of which becomes apparent throughout the film. Judderingly, a discussion develops, in which arguments can no longer be non-committal. Much of the film is about calling out taboos, reading between the lines, looking critically at oneself, and considering whether we truly see each other for what we are. It’s clear that Vos listens and observes sensitively, exposing only what the true situation is: an internal revolution. The documentary viewer can draw their conclusions. And which world lends itself better to a debate about identity than the world of visual art?

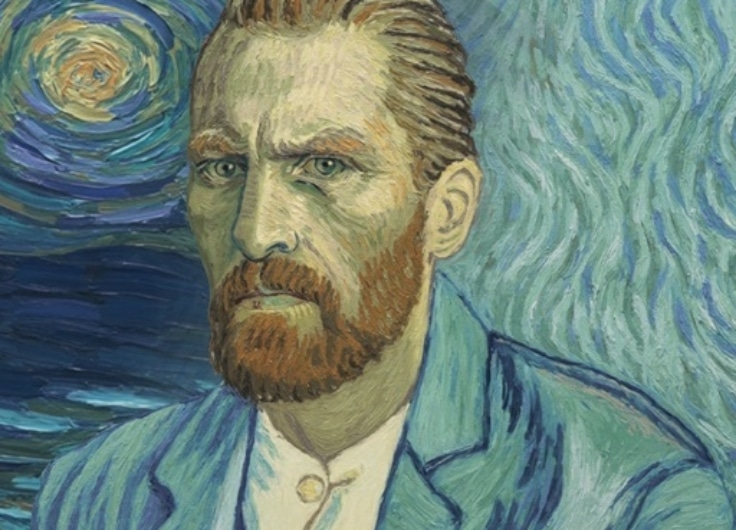

Still from 'White Balls on Walls' with Charl Landvreugd, the Stedelijk Museum's first black policy officer

Still from 'White Balls on Walls' with Charl Landvreugd, the Stedelijk Museum's first black policy officer© Sarah Vos

‘Don’t beat around the bush’

On a terrace, a stone’s throw from the Stedelijk, Vos explains “I didn’t just want to make an art film, but rather a piece rooted in the time we live in, that reflects the struggle that many Dutch institutions and companies are currently going through. The world of the visual arts is sensitive, and communication is so often veiled in euphemisms, that after half an hour you still don’t have a clue what the conversation is actually about. I was very aware of that at the start, and we’d then stop shooting for a minute and I would say, ‘Rein, tell it like it is! Don’t beat around the bush!’ For example, in the start-up phase of the project, there was a really serious and sensitive discussion on the agenda, but I ended up in a meeting where the discussion was all about how well things were going, and how there were just enough resources to survive the pandemic. So I was like, hello!? That’s not what I’ve turned up to make a film about! Gradually though, an openness has emerged that gives the film its strength – a document to which you as a viewer have to relate, and one which typifies the courage of the Stedelijk on this sensitive matter.”

Documentary filmmaker Vos: ‘I said to the director – no fake, socially acceptable scenes’

Landvreugd – the black staff member who began working in this white stronghold – explains in the film that he sees his first task as making it clear to everyone that they have nothing to fear from him. I ask if this was also Vos’ approach to gain access to the Stedelijk? “No, on the contrary, I’ve emphasised before how big the impact of having a camera in a space can be. I’m transparent about that. I always explain clearly where I want to take things so that the main characters know exactly where they stand. I said to Rein too ‘Really think about it, because I don’t want to capture fake, socially acceptable scenes.’ I often know exactly behind which doors the difficulties lie, I have an instinct for that. So I carry on pushing until that door is open of course.”

Trailblazing

Somewhere at the beginning of the documentary, Wolfs openly admits, “I have only done exhibitions with white artists. Some people call that systemic racism and I understand that to an extent.” Vos comments that “he certainly didn’t say that on day one of filming. I think he talks more forcefully now than he did at the beginning. He is also in a delicate position, of course. All eyes are on him, and there are a lot of people who will undermine him given half a chance.”

Yet, more than two years later, Wolfs is still firmly in the saddle, perhaps because of how zealously he continues to scrutinise himself. So much so in fact, that the aging museum has started to become a trailblazer, and shockingly has once again garnered a conservative reaction, this time from one of the most progressive newspapers, in response to the exhibition Kirchner and Nolde: Expressionism. Colonialism. The paper argues that the quality of the art has been snowed under by the moralistic context in which it sits. And so yet again, the museum struggles with criticism from society. With this, Vos’ documentary also considers positions of power, undermining, obtaining, and securing them. It is a moral sketch of how institutions work, and of how policy is put into practice.

Vos: ‘Injustice and power relations are recurring themes in my work’

“Injustice and power relations are recurring themes in my work,” Vos says. “My films feature a lot of meetings. Sometimes the films were even born in meetings where something interesting came to my attention. I like meetings: the national character often reveals itself subconsciously in them. There’s always verbal as well as non-verbal communication. One of my first films was ‘Welcome to Holland’ – Campus Vught (2003), which was nominated for a Golden Calf. At the time, the Dutch government had devised a closed campus model for underage asylum seekers who had exhausted all legal options and were being returned to their country of origin. I chose to shoot the pilot run of the model from the perspective of the people of the Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers (COA) because it struck me as a hugely complex task to have to send these young people back to where they had come from.”

During the turbulent period in which Vos followed the campus, one of the directors resigned and the entire group of young people ran away. Vos explains, “The police looked on helplessly. While the unaccompanied minors increasingly began to rebel, one boy – Theophile from Angola – became the leader of the group. Theophile negotiated on the group’s behalf with the campus management, one of whom was such a typical Dutch manager – complete with an elephant-patterned tie. He spoke with the tone of my friend, I tell you… my friend… It had me on the edge of my seat.”

Less attention

Vos made the documentary Curaçao in 2010, together with her regular cameraman Sander Snoep, and was awarded the Dutch Film Critics’ Prize. The film considers how the collectively concealed past is still palpably present in the social relations of this former colony. Vos says that “that film is a kind of diptych together with White Balls on Walls. When I first went to Curaçao on a holiday, I was shocked to see how we treated black Curaçaoans there as if they were foot soldiers, and nobody seemed to stand up against it. I thought, how can this be? That’s when I started to dive in deeper. At one point, the manager of an Albert Heijn branch there wanted to recruit black staff members into the management team. I asked if I could follow that process and I was allowed to. He didn’t succeed whatsoever. Because there had never been any recognition of the history of slavery and the suffering it has caused, everyone was still in the habit of thinking – that’s the white man, I need to show respect, I can’t be on the management team. Those people said that themselves, and I found that incredibly disconcerting. In White Balls on Walls you can see the turnaround: how that recognition process, which concerns us all, is now getting underway.”

Vos goes on “I also encountered my own blind spot during the creative process and it was Charl Landvreugd who pointed it out to me. He said: ‘The art you like, and what hangs on the walls here, is also inspired by the white male canon.’ I walked around with that thought for a week thinking: ‘Huh? But I’m so open-minded and free, right?’ But he was right.”

Documentary filmmaker Vos: ‘I also encountered my own blind spot’

When the museum’s director Wolfs finally managed to bring on board some criticasters of the old policy to the Stedelijk, two black men were appointed to the team. In addition to the white balls, there are now significantly more black balls on the walls. There are, however, still considerably fewer boobs on the walls. So how is that possible?

“Curator Beatrice von Bormann says in my film that, despite having studied feminist art history, she has spent years putting together blockbuster exhibitions from the white, male canon. She says: ‘You first have to be aware of the fact that you are part of a system that you help sustain.’”

Curator Leontine Coelewij says in Vos’ film that she learned nothing about African, Asian or South American art during her education. “If you are constantly being sent in one direction, then it is extremely difficult to think differently”, warns Vos.

“Through starting to have this discussion, a space was created for both of these women to be able to give substance to their professional ideas. I found that an interesting process to follow because it also broadened my own perspective. But I also saw pain, such as in the conversation in which I asked Coelewij: ‘How did that work before?’ And with a sense of understatement, she replied: ‘Let’s just say that there was less attention for that.’”