Increasing Drought, a New Enemy for the Netherlands

For centuries, the Dutch have been fighting against the threat of water. For the past few years – bitter irony – they have also had to deal with a water shortage. That shortage is becoming ever more serious and is now causing problems with shipping, agriculture and subsidence. Solutions are needed urgently, but none seem readily available.

Travelling by train through Europe I see wide yellow strips and endless, dry fields… Stanzas from Memory of Holland, a poem by Hendrik Marsman (1899-1940), fly through my head as I stare out the window of the Thalys train. This is my first trip in three months. Services between Brussels, Paris and Amsterdam had all but stopped due to corona. However, since the end of May 2020, travel between the Netherlands and France is once again possible.

© Freepik

It is striking how the colour of the landscape on both sides of the high-speed rails hardly changes. The fertile green that the few-and-far-between passengers are used to seeing is a rare sight. The landscape is a patchwork of yellow squares varying between PMS 108 and 135 on the Pantone colour chart. Fields resemble pieces of skin from which minute hairs have been pulled out by a powerful sticking plaster that was left on for too many days. Sometimes, it looks almost orange, sometimes like the blonde tresses of a Frisian fierljepper. Now and then, the colour edges towards brown. Quite a few patches are nothing more than dry, bare earth. Here and there, groups of bored Holstein and Limousin cattle search for scarce grazing. Anyone travelling through the Benelux can see that in 2020 we are not only in the grip of corona but also in the clutches of an even more deadly killer: drought.

That a lack of water could be a threat is a notion that has only taken hold in the past few years

As polder dwellers in an enormous delta, the Dutch have been used to protecting themselves from water for centuries. During those centuries, the sea, both friend and enemy, has created wealth. In our pre-school days, we learned about rising sea levels and threatening floodwaters. But our awe of the sea has given way to new challenges: now we must learn how to protect ourselves from water shortages. That a lack of water could be a threat is a notion that has only taken hold in the past few years.

Breaking record after record

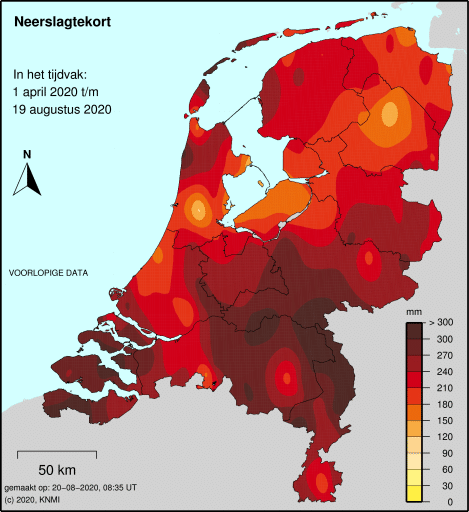

The grand rivers still meander slowly through endless lowlands, but they have narrowed in recent years. Lately, the hot summers have gone hand-in-hand with a lack of rain. The first six months of 2020 were the warmest since records began in 1706. This spring there were 806 hours of sunshine, with a spike of 836 hours in the Zeeland city of Vlissingen (compared to the usual 540 hours in a ‘normal’ spring). For the third year in a row, the water map of the Netherlands has been in the red. In 2018 there was a scarcity right up until the beginning of winter. In 2019 there was not enough rainfall to make up the shortages from the previous year. Even the deep-lying groundwater reserves are becoming increasingly exhausted.

Precipitation deficit in the Netherlands, measured from 1 April to 19 August 2020

Precipitation deficit in the Netherlands, measured from 1 April to 19 August 2020© KNMI

During the time I spent writing this article in 2020, it barely rained. Sunshine and warm breezes have featured as constantly in Dutch lives as the numbers of daily infectious corona cases announced by the National Institute for Health and the Environment. The supply of water to the great southern rivers, the Rhine and the Maas, was insufficient, though some hard rains in mid-June did provide for more water locally. But a dry riverbed cannot take up water so easily, so even when there is a lot of rain, it doesn’t trickle down into the subsoil but runs off and disappears into ditches and sewers.

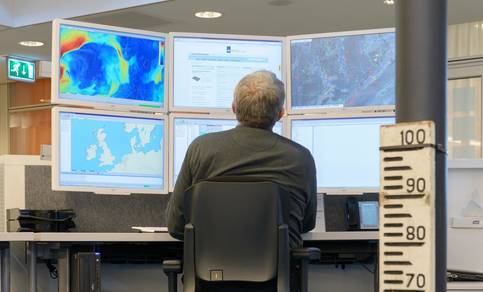

The Water Management Centre in Lelystad

The Water Management Centre in Lelystad© KNMI/Tineke Dijkstra

Since the beginning of 2020, the rainfall shortage has been above the 2018 level, according to the Drought Monitor (Droogtemonitor). This meticulous record of the state of water is compiled and published by the Water Management Centre in Lelystad. Its national monitoring centre in the middle of the Flevo Polder resembles the Control Room at NASA in Houston. From the tiniest brooks to the majestic Rhine, from inland waterways to the expanse of the IJsselmeer: not a drop of water escapes the attention of those behind the endless computer monitors. In a state of serenity, the engineers at the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management manage water like modern-day Moses’. When required, water can be moved where it is needed, from one region to the other, at the touch of a button. Every two weeks, they publish their report, which is not only mandatory reading for farmers, but also for those involved in shipping, like Twan Brummelkamp, who is Captain of the inland vessel, Progres, owned by the Bosman Group.

Twan Brummelkamp, aboard his inland vessel, Progres.

Twan Brummelkamp, aboard his inland vessel, Progres.© Stefan de Vries

Two or three times a week, he transports containers from Rotterdam port to Germany, and vice versa. Water levels have an influence on the weight of the cargo. ‘On a normal sailing, we carry about 250 containers, which means 250 fewer containers on trucks on the highways,’ he tells me from the futuristic cockpit of his 135-meter long ship. ‘Furthermore, the emissions from each ton we carry are much lower in comparison with road transport.’ But if the water levels are too low, then barges can only carry lighter loads. When the Waal River was at an all-time low in 2018, the Progres was pushing barges that were only partially loaded towards the Ruhr Valley. In some places, there was less than 30cm between the ship’s hull and the riverbed. Great skill is needed to sail in such conditions. ‘Before you know it, you are stuck,’ says Brummelkamp. ‘Last week, again, we had to pull a ship because the captain had miscalculated the shallows. It took hours.’

Due to water shortage, ships have to sail with a lighter cargo than normal.

Due to water shortage, ships have to sail with a lighter cargo than normal.© Stefan de Vries

While we chat, two Serbian seamen are cleaning the Progres. Everything shines on Brummelkamp’s ship. The young skipper seems content: ‘For us, this year hasn’t been as bad as 2018. In southern Germany, there’s been more than enough rain and the river depth is quite good.’ Yet, the threat still looms. The lower the water level, the fewer containers can be shipped. If the water situation worsens, businesses might choose a different means of transport. This is not ideal for them, nor for the skippers since they are generally paid by the trip; whether the barge is full or half-empty makes no difference. Brummelkamp has had to adjust: ‘We have certainly learned from the dry spells. Ships are a bit lighter, so they can take on more cargo. This is how we are preparing for unpredictable waterways in the future.’

Ominous signs on the horizon

Farmers are also concerned about increasingly erratic weather. In Zeeland Flanders, where the polders merge seamlessly into stunning seventeenth-century skies, drought has become a recurring problem. Though the busy port of Antwerp is only a good 15-minute drive away, the farms here are ‘sunk in a great space, scattered throughout the country.’ One of those farms belongs to Piet and Ellen de Feijter. It’s been held by the family since 1811. The couple produces, amongst other things, sugar beets, wheat and, mainly, the famed Zeeland onions. These fields are some of the most fertile in Western Europe, but the previously predictable weather has become increasingly fickle.

For the first time it seemed that, even in Zeeland, where water is in the population’s DNA, abundant rainfall is no longer a given

At the end of 2018, I went to see the de Feijters for a story. It had been a cork-dry year. The onions, usually as big as tennis balls, were more the size of ping-pong balls. For the first time it seemed that, even in Zeeland, where water is in the population’s DNA, abundant rainfall is no longer a given. The extreme drought in that period caused a moment’s doubt about the survival of the more than two-hundred-year-old farm. Now, a good eighteen months later, Ellen is a bit more optimistic. ‘For weeks it was the same, sunshine and wind from the East that dried out the soil. At the end of April, a lot of seeds had not even been sown. We took a gamble and sowed everything. And there was, in the end, just enough rain to allow for sprouting. In June, we got 65 millimetres of rain in only two days. If that hadn’t happened, I’d be telling you a different story today.’

© Akkerwijzer/Ellen

The local differences were immense. ‘We’ve got some lovely beets now, 60-70 centimetres high. But two polders further, the situation is completely different. There, the soil is different. A good yield is 100,000 beets per hectare. If you get 80- to 90,000, you’re doing well. But some of the neighbouring farmers are barely harvesting 10,000. Of course, regardless of how many beets come up, the initial expenditure is the same. In the west of Zeeland Flanders, the beets have been ripped out. The farmers there have decided not to even sow this year.’ But not all the signs are positive. ‘Flax has been difficult this year and that seems to be the case everywhere. Beyond the dike, you can see soil through the flax, and that’s not good.’ The de Feijters are hoping for a moderate summer after this dry spell. The signs are good, says Ellen. ‘For us, things are going well, but some of our colleagues have nothing. If you bike across the dike, you almost get a stomach-ache from what you see. For now, our beets are growing… until the temperature rises to 35C, and there’s no rain for six weeks. Then I fear the worst. Of course, uncertainty is part and parcel of farming,’ says the Zeelandic farmer, but there are definitely some structural climate changes. ‘In 2016 we thought the heat was just a one-off. Then came 2018. And now, the threat of drought returns every year. I don’t really know what we should do. I don’t have the answer yet. Climate change is real. Those who believe it will never happen have their heads in the sand,’ she says melancholically, but with a good understanding of reality.

Homes under threat

Water shortages lead to poor harvests and difficult navigation for transport, but also to subsidence. It is estimated that over a million houses in the Netherlands are at risk of slipping off of their foundations. Houses built before 1970 are particularly at risk because they are built on wooden struts. If the struts dry out, they rot. Cracks appear in the walls, the house starts shifting and if the foundations are not secured, it can become uninhabitable. Foundations on clay and peat can also subside due to drought and soil erosion, respectively. Repair costs, very quickly rising into tens of thousands of euros, are the responsibility of the homeowners. Preventative measures are technically troublesome, but not impossible. Communities can sometimes keep water levels under control by, for example, installing sewer pipes that allow groundwater to flow away. But this has not been happening everywhere. And, of course, due to the corona crisis, local governments now have much less to spend. Finding solutions for subsidence and salinisation is no longer a priority.

Water shortages lead to poor harvests and difficult navigation for transport, but also to subsidence. It is estimated that over a million houses in the Netherlands are at risk of slipping off of their foundations.

Water shortages lead to poor harvests and difficult navigation for transport, but also to subsidence. It is estimated that over a million houses in the Netherlands are at risk of slipping off of their foundations.A grand connection

At the national level, governments in Belgium and the Netherlands are slowly waking up to the problem. The Flanders Environment Agency, the organisation that oversees the integrated water policy, is currently working on a plan to tackle water scarcity. In the Netherlands, the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management published a report in 2019 that included recommendations for improving the soil’s resistance to drought. Everyone understands the urgency. The water management for which the Netherlands is famous worldwide is taking a completely new turn. The feared “voice of the water” in the poem by Hendrik Marsman has turned into a plea for even a whisper of water in some regions. In the 1940s, another great Dutch poet, J. Slauerhoff (1898-1936), wrote the famous lines ‘I do not want to die in the Netherlands, And rot in the wet ground.’ The viability of the land can still be disputed almost a century later, but a burial in wet ground is becoming a thing of the past. It’s a strange situation: the battle against too much water has evolved into a battle against too little water. Under a relentlessly burning sun, a parched land begs in vain for release.