Intimacy Set Free: Bertien van Manen at the Antwerp Photo Museum

With a 35mm camera in hand, Dutch photographer Bertien van Manen has been travelling since the 1970s to capture the changing world at the human level. From the Appalachians to China, from the kitchen to the bedroom. The retrospective Wish I Were Here in the Antwerp Photo Museum shows an eventful and intimate history.

A young woman with red lips and a white hat and blouse sits on her haunches with closed eyes. Her arms are flung loosely around her husband’s shoulders, who kisses her on the neck. A little further on is their son, who is distracted by the busy Odessa station. It is as if the family members barely realize they are being captured on camera, so much are they in the moment.

Odessa Station, Vasja, Lena and their son Styopya, from the series 'A Hundred Summers, a Hundred Winters', 1992

Odessa Station, Vasja, Lena and their son Styopya, from the series 'A Hundred Summers, a Hundred Winters', 1992© Bertien van Manen

That is what Bertien van Manen’s (b. 1942) entire retrospective in the Photo Museum in Antwerp (FOMU) does: the exhibition lets you look over her shoulder, into intimate moments and private living rooms.

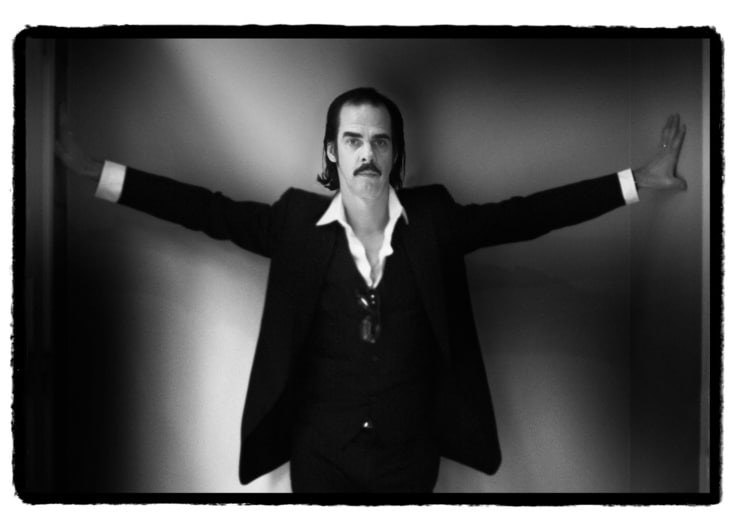

Those accidental, heartfelt images could never have existed. Van Manen worked as a fashion photographer in the 1970s and was used to sharp shooting perfect images. That was until she got her hands on The Americans by photographer Robert Frank: while everyone was working with large-screen cameras, he captured raw, post-war American life with a small Leica.

For Van Manen, Frank’s unpolished photos were a relief. This is what she also wanted: to break free from the rigid framework of fashion photography and step into the shoes of her fellow man on the street.

Pocket sized

So she takes her first road trip. In 1975, she leaves for Budapest on her own. She photographs, among other things, milkmen, endlessly waiting travellers in the station, and a boy with a blurred head but a razor-sharp eye. Her love for travel and documentary photography is born.

In the 1970s and 1980s, reports came out about nuns, the conflict in Nicaragua and – closer to home – the first generation of female migrant workers in the Netherlands. Through a series of black-and-white images, we see how she becomes more and more interwoven in the lives of these women: in one photo a group of women are still working in a factory, in another someone prepares a washbasin over a fire while her son stands beside, a towel wrapped around him.

Van Manen wants to be able to take a photo at a glance, as a snapshot of daily reality

Would Van Manen be able to create such intimate work without her small, fully automatic cameras? This is doubtful. The cameras fit in her pocket and aren’t that threatening – more likely to be forgotten. They are low-tech devices, but that doesn’t matter. She just wants to be able to take a photo at a glance, as a snapshot of daily reality.

Human sized

And yet, Van Manen later distances herself from those early years, precisely because the shots still are not spontaneous enough. She may have been keeping faithful to the conventions of social photography – where contrasting black and white photos are the norm – but not to herself as a photographer.

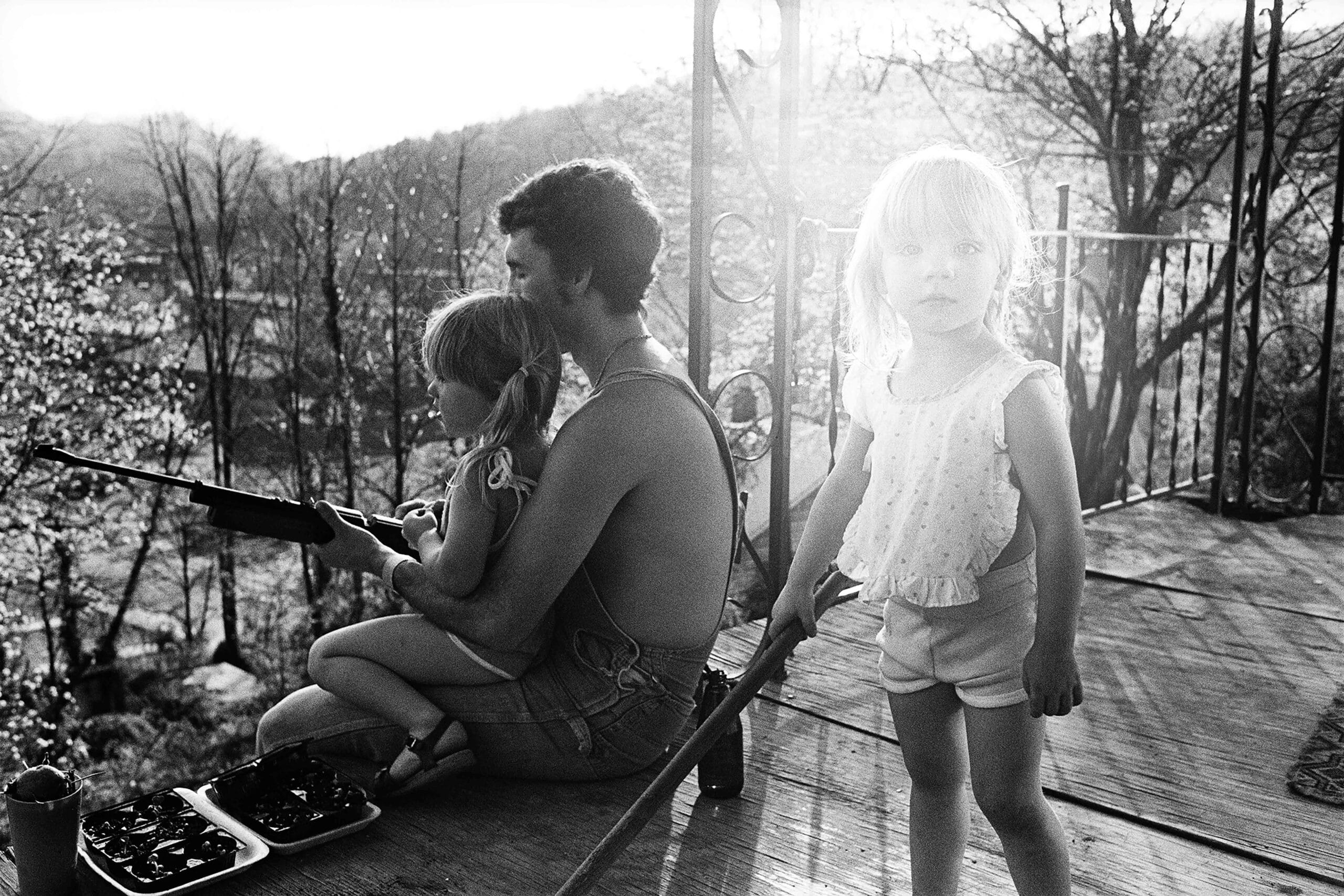

It can still be more uninhibited, more personal and above all: messier. She rediscovers that freedom in the American Appalachians. Fascinated by the raw but also hospitable mining communities, she returned no fewer than nine times between 1985 and 2013. Gradually, she becomes a friend at home, witnessing babies being born and little girls growing up into make-up clad teenagers.

Amanda on porch, Cumberland, from the series 'Moonshine', 1987

Amanda on porch, Cumberland, from the series 'Moonshine', 1987© Bertien van Manen

Over this long period of time, not only do the subjects through Van Manen’s lens evolve, so do her photos. Initially, the images are fairly constructed and seem to be outside of time – a girl hangs in the air on a swing that threatens to fall at any moment, a toddler stands like an angel in a spot of light on the veranda. Over the years, the photos become looser and colour also comes into her work. She seems to capture the zeitgeist more: the photos of a woman jogging in a high visibility jacket or of a man looking in through the kitchen window radiate the America of the 2000s.

In the Appalachian series, Van Manen sees people’s lives change against the background of the declining mining industry. Meanwhile in China, where she travels from 1997 to 2000, the major political, cultural and economic transformations are called ‘progress’.

Tao in her dormitory, from the series 'East Wind West Wind', 1998

Tao in her dormitory, from the series 'East Wind West Wind', 1998© Bertien van Manen

What particularly interests her in all these evolutions – and distinguishes her from other photographers – is the impact of these intimacies. She even delves into the bedroom. In one of the last galleries of the FOMU exhibit, a few canvases are hung together on which the photos of that journey through China are projected. Because the images are constantly changing we don’t really know where to look, but one thing stands out: Van Manen is right on top of her subjects. A sleeping family flashes past, a girl dressing behind a cloth, a couple dancing intimately, a woman crying with a telephone cord in her hand.

Research

After more than forty years, Van Manen’s archive is so vast that new exhibition choices can always be made. This becomes clear in the gallery showing images from the former Soviet Union.

On one side there hang photos from the book A Hundred Summers, a Hundred Winters, her international breakthrough in 1994. They radiate a wry but warm glow with predominantly red, green, and parchment-colored tones.

On the other wall, we view a selection from the later book Let’s Sit Down Before We Go, which gives a very different impression of that same journey from Russia to Armenia. The photos of an overexposed theatre or a sunbather in fluorescent green grass literally appear lighter, and therefore more playful.

Odessa, Ljalja, from the series 'Let's Sit Down Before We Go', 1991-2

Odessa, Ljalja, from the series 'Let's Sit Down Before We Go', 1991-2© Bertien van Manen

That Van Manen’s archive is a world in itself was also noted by Hans Gremmen, who collaborated on the exhibition and compiled her catalogue raisonné Archive (MACK, 2021). In the exhibition, we see the fruits of his research – from negatives about a collection of cameras, to bulging folders. With this look behind the scenes, we also learn that Van Manen often travelled back to the people who she photographed with her books. She never lets her subjects go.

Binder 25, Sheet 892_1, from the publication 'Archive', MACK, 2021

Binder 25, Sheet 892_1, from the publication 'Archive', MACK, 2021Perspectives

You could call Bertien van Manen a people photographer: she seems to be all about the people who cross her path, whether for a second or for a decade. But in one of her last series, Beyond Maps and Atlases, she was still drawn to landscapes. In 2015, she travels to Ireland, shortly after the death of her husband. Without knowing what she is looking for, she is guided by the vast, mythical nature, the emptiness, the nothingness. The country passes before our eyes like a road trip through a slideshow.

Yet this series is also about people, more specifically: about the person she is herself. It is as if the photos reflect her state of mind after her husband’s death. She is creased like the misty grass, broken like the tree trunks, fierce like the crashing waves, tarnished like the carcass of a lamb, but above all free. Free as the birds that fly in the evening, free as the infinite ocean, free as the two walkers as the world stretches before them on a deserted beach.

Bertien van Manen in FOMU, Antwerp, is on until 28 August, fomu.be