Breaking New Ground in Archaeology Using Dutch Satellite Imagery

Rather than digging in the mud, future archaeologists will work from behind their computers using satellite imagery to detect archaeological sites. And a young Dutch woman plays a part in it.

Iris Kramer (b. 1993) is the founder of ArchAI, a company that uses artificial intelligence (AI) and satellite imagery to detect, alert and monitor archaeological sites. Compared to traditional archaeology, this way of working is ground-breaking. Born in the Netherlands, based in Southampton but travelling the world, Iris spends considerable time educating the field about the advantages offered by this technology. Overall, it’s faster, more accurate and more sustainable.

Inspired by self-driving cars

Iris obtained her bachelor’s degree in archaeology at Leiden University. She continued studying for a master’s degree in archaeological computing, for which she moved to the University of Southampton. At that time, she was deeply interested in self-driving cars and their use of AI and became intrigued by the thought that the same technology could perhaps be used in archaeology. For her master’s thesis, she explored the current state of research on automated detection for archaeology and found out that it was very limited. But if self-driving cars can take to the road, then that same technology should certainly be usable for archaeology, Iris argued.

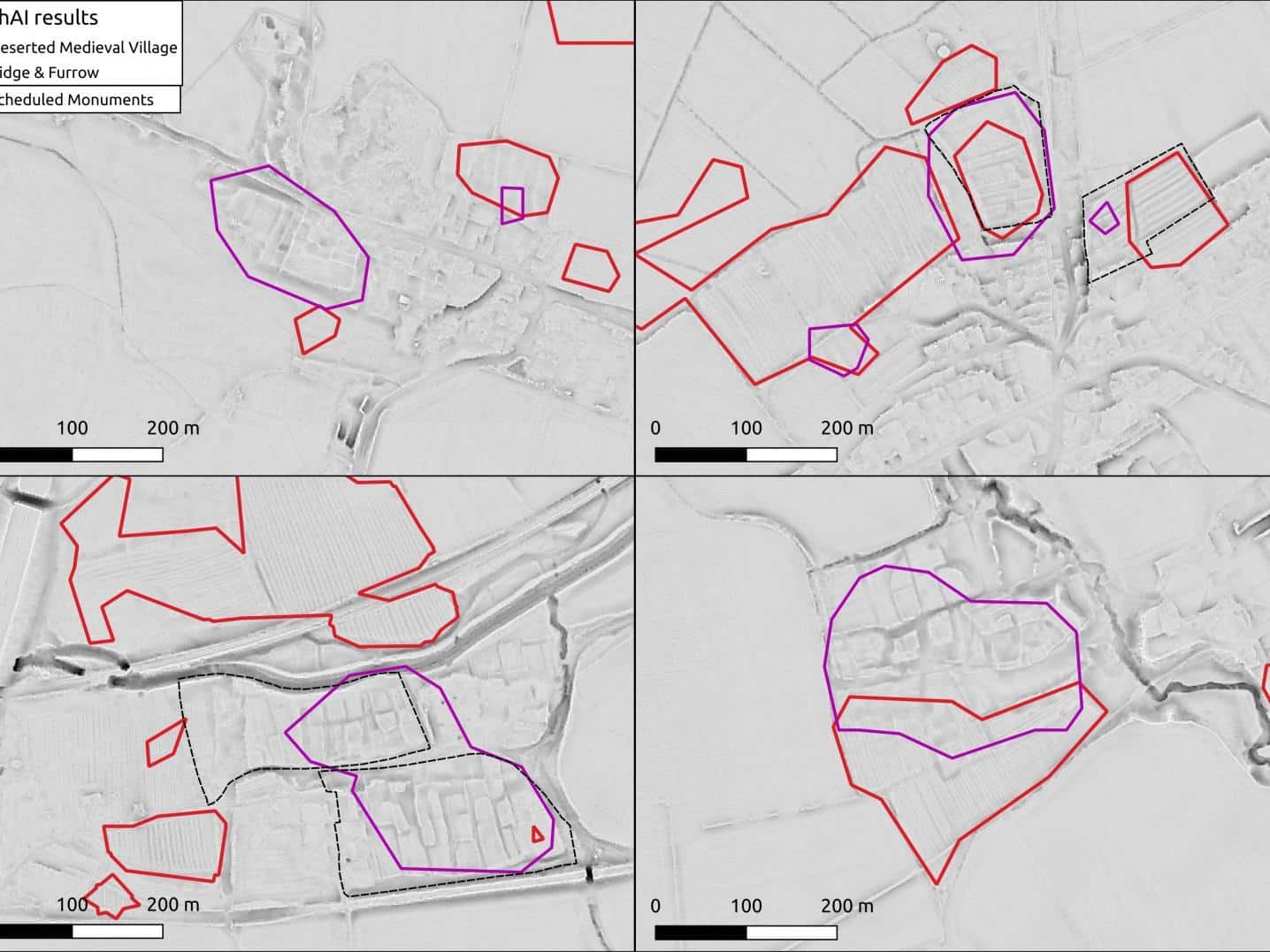

A LiDAR image showing image segmentation results of ridge and furrow earthworks (Medieval ploughing remains) in Northumberland, England. The results are subdivided into their preservation height which helps our customer, the Forestry Commission, decide which locations cannot be planted with new trees.

A LiDAR image showing image segmentation results of ridge and furrow earthworks (Medieval ploughing remains) in Northumberland, England. The results are subdivided into their preservation height which helps our customer, the Forestry Commission, decide which locations cannot be planted with new trees.© ArchAI

Using AI for archaeology

“I discovered that AI is already being used in geography to detect landslides. Just like any archaeological site, every landslide is unique each time they occur. This inspired me to create the same kind of technology for my Master’s thesis, aimed at detecting burial mounds in landscapes. First by telling the computer what to look for, and then to have the computer train itself, like the deep learning in self-driving cars. The computer learns from the variations between the burial mounds and internally creates patterns to find other burial mounds, adapting to new landscapes. That was much more exciting than simply telling it what to look for, because it reached much higher accuracies!”

Coding course

After receiving her Master’s degree, Iris took a coding course in Amsterdam. “It was kind of a coding course for unsuccessful young professionals that wanted to change their career because they couldn’t find a job. I didn’t have a job because I had just finished my Master’s and wanted to develop AI technology. I learned how to code in three months and used that knowledge to apply for PhD positions.” Eventually, she started as a PhD student in deep learning to detect archaeological sites on earth observation data at the University of Southampton, where she could further develop the technology.

Iris Kramer, founder of ArchAI

Iris Kramer, founder of ArchAI© Iris Kramer

“A couple of years in, I asked myself: what am I going to do with this technology once I finish my PhD? You always need to publish in an academic setting, while for me it would be much more useful to discover archaeology nationally and internationally and create a team.” Towards the end of her PhD in early 2020, she thus founded ArchAI. With the help of business accelerators and the prestigious Royal Academy of Engineering enterprise fellowship, she obtained the necessary funding and the knowledge of advanced engineers and business experts.

Market education

The technology of using satellite imagery and artificial intelligence is so novel in the field of archaeology that wherever Iris comes, she needs to explain what it is. People are suspicious of AI or fear they will lose their jobs. By speaking to lots of people and visiting many different conferences, she is making more and more people aware of the benefits of using satellite imagery to detect archaeological sites. “The realisation that you can do this very successfully using satellite imagery instead of with aeroplanes is a whole shift in the mindset of archaeologists,” Iris says.

Among the first customers was the National Trust in the UK, for who ArchAI digitised orchards in historical landscapes based on maps from the 1900s. Without much effort, ArchAI was able to do this at a national level with the help of AI, thereby replacing the work of countless volunteers for years. The project was reported in The Guardian and the resulting data set will be made freely available for research.

Iris Kramer: ‘There is so much more potential for using satellite imagery for monitoring and alerting: looting, animal burrowing, climate change in cliff erosion, detecting historic features on historic maps and combining everything’

For England’s Forestry Commission, ArchAI investigated the patterns of medieval ploughing that are still traceable in the landscape in the form of earthworks, basically “small humps and bumps”, using LiDAR data. LiDAR, also known as Airborne Laser Scanning, is a revolutionary technology that creates a 3D-model of the landscape and can reveal archaeological earthworks, even those hidden underneath tree canopy, bringing to light even small humps and bumps. By using this technology, ArchAI helped the Forestry Commission decide where they could plant new trees or which areas should be protected for archaeological research. By the width of the ridge and furrow, ArchAI could even detect whether they were made by a medieval plough or a more modern steam plough.

Increasing awareness of the past

ArchAI’s technology can be used for different purposes, from development-led archaeology (researching possible archaeological traces on construction sites, which reduces the risk of destruction and costs) to detecting and monitoring archaeology and possible threats like coastal erosion. “The ultimate goal is to increase people’s awareness that archaeological sites are all around us and that our past is important,” Iris says. “Only when you know where archaeological findings or historic features are located, you can protect these landscapes. Or, in the case of destroyed landscapes, we can show where hedgerows and ponds used to be, so that the landscape can be recreated from a historical perspective, which is better for wildlife and nature. So basically, we are improving the environment by applying a historical perspective.”

Take for example the hedgerows in the United Kingdom. “Roughly a century ago, most of the hedgerows between the fields were taken out in order to create fields on a larger scale. These hedges were very important for insects and birds. The country now wants to put the hedges back, but in their historical location. So people need to know where the hedges were, but even though they disappeared only a century ago, that knowledge has been lost. With ArchAI, we want to play a role in restoring the landscapes to a more human size again, reducing the scale and creating a nice symbiosis between humans and animals.”

Archaeologist, entrepreneur or computer scientist

Iris has hired one full-time employee at ArchAI, tasked with further developing the computer science side so that she can concentrate on the business development side. When asked if she feels more like an archaeologist, entrepreneur and/or a computer scientist, Iris replies: “A bit of everything. I find it really exciting to constantly change hats. In London, I’m an entrepreneur. When I go back to Southampton, I feel like a computer scientist and an entrepreneur. But whenever I’m online and on Zoom and in conferences, I mostly feel like an archaeologist.”

Changing hats also applies to the role Iris plays among the people she meets. “On the one hand, I am an early career researcher who feels connected with other young researchers. On the other hand, I have conversations with policymakers and business owners. Sometimes, I have to ask stupid questions, and people will think I’m really young. As long as I’m not too embarrassed about it, and as long as I get the answer I need for ArchAI, it can be worth making a fool out of myself. I’m here for ArchAI, and I’m here for archaeology. It’s not a burden but it’s definitely a responsibility that I carry for the company. I also care about our employee and consultants.”

A LiDAR image showing image segmentation results of ridge and furrow earthworks (medieval ploughing remains) and deserted medieval villages in England.

A LiDAR image showing image segmentation results of ridge and furrow earthworks (medieval ploughing remains) and deserted medieval villages in England.© ArchAI

“Fieldwork is a really fun part of archaeology that I haven’t done at all for many years now. But I’m constantly looking at archaeological sites from behind the screen instead of on the ground, so it feels like a kind of fieldwork. I can often see more on the screen than in the field. Small elevation details of half a meter, which are almost certainly overlooked when you are in the field or in a forest, are visible on the screen. When you are in the field you can walk across an archaeological site without even noticing it. The site might be very big so you can’t see the full extent, and the vegetation might disorient you,” she explains.

Iris Kramer: ‘The ultimate goal is to increase people’s awareness that archaeological sites are all around us and that our past is important’

“One of the market education parts is that a LiDAR image can sometimes be enough, you don’t need the fieldwork. Most archaeologists today still want to go out in the field, but the data don’t lie. In one day we can look at a much bigger area or even examine other dimensions (like elevation differences) from behind our computers. Plus, it takes much less time than travelling to an archaeological site.”

Iris doesn’t rule out fieldwork completely: “There’s definitely still a place for doing fieldwork, especially for doing further geophysics and excavations. You can work more specifically: digging up things can be precisely targeted, more specified.”

Earth observation is the future

Iris is now looking at how ArchAI can expand its market internationally. From a project in the Mayan area in Mexico, she learned that AI works internationally as well. “The future of cultural heritage lies in earth observation,” she says. “It is not great for the climate to be going out into the field to dig up things. When we use earth observation data that is already there, there is so much that you can capture from that. Satellites are not expensive compared to using aeroplanes that fly specifically for the purpose of taking pictures, and they are becoming more and more available. There are very frequent fly-overs, some once every seven days, and some satellites take an image every day at a really high resolution. There is so much potential for the future, but as archaeologists, we don’t have the skills yet. We have to address the skills gap.”

She continues: “We are not just thinking about detecting archaeology, there is so much more potential for using satellite imagery for monitoring and alerting: looting, animal burrowing, climate change in cliff erosion, detecting historic features on historic maps and combining everything. There’s a lot of unrealised potential – for others to explore as well. It’s really exciting, and it’s almost easy since there is so much low-hanging fruit!”

This article was originally published on DutchCulture (20 October 2022).