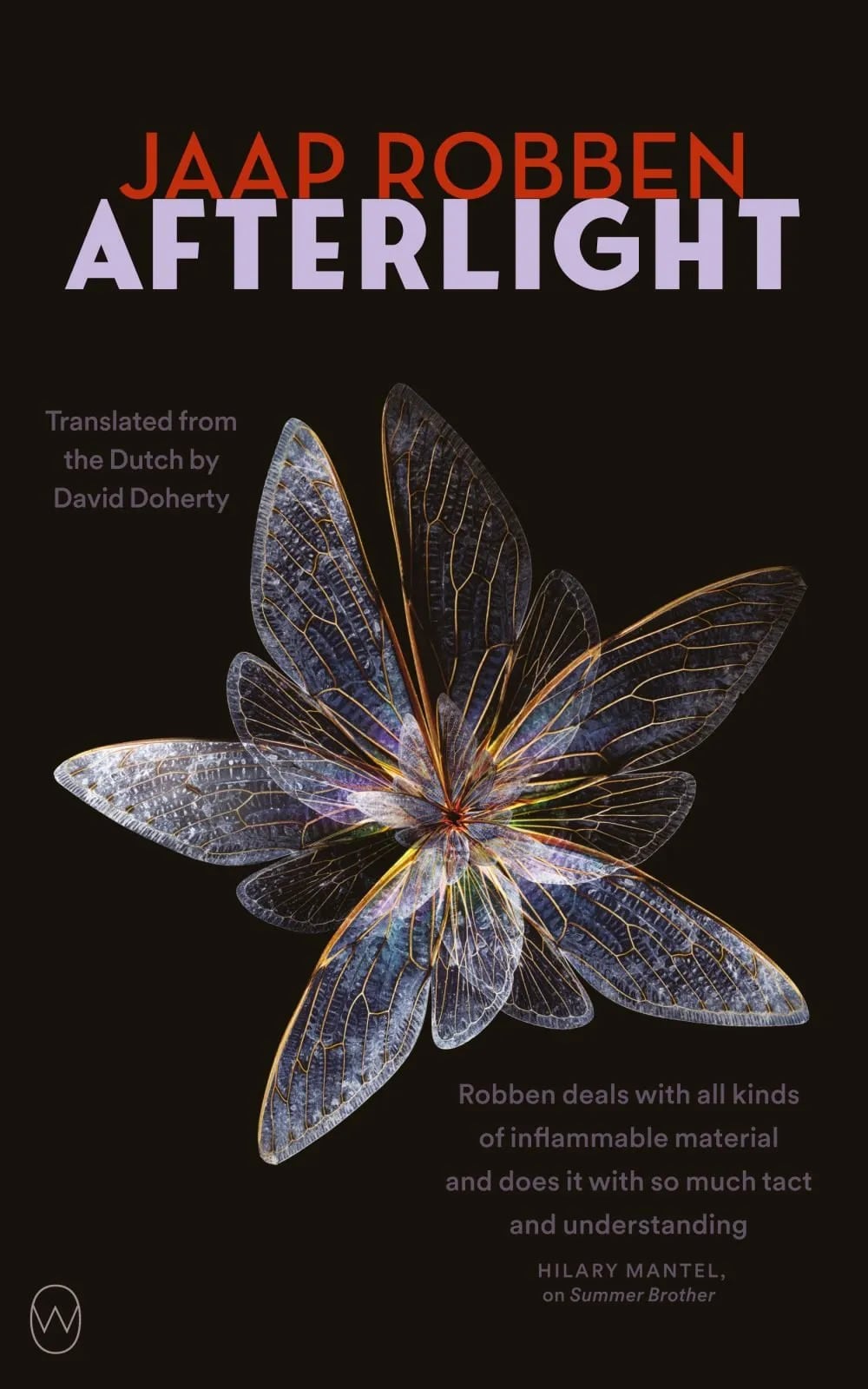

Jaap Robben’s Mastery Shines Through In The Dialogues Of ‘Afterlight’

In his novel Afterlight, the acclaimed Dutch poet and author Jaap Robben describes a complex love, set in Nijmegen from the 1960s through to today. The lovers, Frieda and Otto, are subtly fleshed out through dialogue and their relationships with other characters.

Afterlight came into being with support from the Municipality of Nijmegen, intending to give literary space to the history and identity of the city by the Waal River in Oost-Nederland. In the same vein, A.F.Th. van der Heijden previously wrote De ochtendgave (‘The Morning Gift’, 2015), set in the seventeenth century, in the era of the Treaties of Nijmegen.

For his novel, Jaap Robben (b.1984) dipped into the city’s more recent history, the strictly Catholic Nijmegen of the early 1960s. On the thick ice of the Waal, a coincidental meeting occurs between Frieda, a young flower seller, and Otto, a married professor at the university in Nijmegen. The two soon begin an affair that is undesirable for several reasons, but love will not be suppressed, bringing with it all the associated consequences.

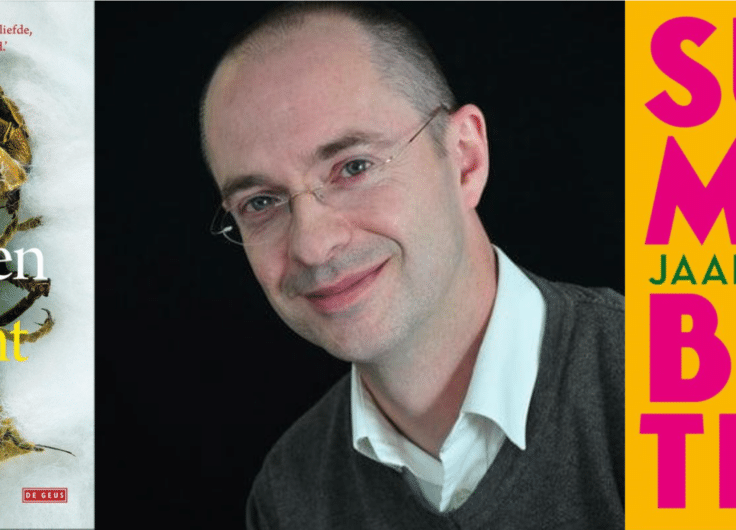

Jaap Robben

Jaap Robben© Charlie De Keersmaecker

We view the story through the eyes of Frieda, now eighty-one years old, who has ended up in a care home after the death of her husband. Flashbacks from the 1960s alternate with chapters from the present. In his novel, Robben – who lives in Germany, but not far from Nijmegen – has subtly brought historic Nijmegen to life. In interviews after the publication of Afterlight, he explained that he dipped into archives and pored over old photos and maps of the city. It turns out to have been time well spent, as even residents of Nijmegen have learned new things about their city. About the poverty in the Benedenstad, the lower parts of town, for example, where many houses along the winding alleyways were more or less uninhabitable and where society’s rejects gathered.

The mood of a society dominated by the Catholic Church is penetratingly reflected. Couples wanting to reserve a room in a guesthouse had to show that they were married at the time. It’s hard to believe now how tight the pastor’s grip was on the lives of religious citizens, or how stifling the effect of his decisions on those who fell victim to them. Without giving away too many spoilers, in that atmosphere, people tended to keep quiet all their lives about far-reaching personal events.

The mood of a society dominated by the Catholic Church is penetratingly reflected

In contrast to the characters from You Have Me to Love and Summer Brother, Robben’s two previous novels, the main characters in Afterlight are less cut off from society: this time the author seems to want to tell a story about completely ordinary people. Frieda and Otto’s character traits are not explicitly sketched but take shape in relation to other characters. For instance, Robben doesn’t mention that the elderly Frieda is sometimes a little stubborn. That becomes clear naturally in a phone conversation she conducts with her son while in the care home:

‘Would you like me to come over?’

‘There’s no need to worry, son.’

‘Did you open the curtains today?’

‘Mmm-hmm.’

‘Mu-um?’

‘What?’

‘Are they open or not?’

‘I was just about to …’

It is precisely in such dialogue that the author’s mastery shines through. They come across so naturally, as a reader you don’t doubt their authenticity for a moment. In that respect, Robben has grown as a writer. The main characters in his debut novel, the strongly plot-driven You Have Me to Love, weren’t talkers, so there was less dialogue in the book. In Afterlight the characters acquire flesh and blood through the dialogues. On a communal outing along the Meuse, for instance, Otto and Frieda have the following conversation:

‘Are you crying?” Otto asked, after we had been sitting for a while. He sounded shocked.

‘No.” I heard the wobble in my voice. Tears had wet my cheeks without me noticing.

‘What is it?’

‘Nothing.’

‘And yet you’re crying?’

‘I want to go on seeing the world the way we see it together.’

‘Oh, Elfie, come now.’

The characters are not stereotypical and the author doesn’t restrict himself to simple armchair psychology. For Robben, a sympathetic portrayal of a character doesn’t mean that they cannot make the wrong choices. When Frieda hits a carer in the face at the care home, it’s not explained in an obvious way. Only after a couple of narrative interventions and leaps between 1963 and the present can the reader understand what sparked her outburst of rage.

In the chapters set in the present, Robben broaches a couple of pressing social themes

In the chapters set in the present, Robben broaches a couple of pressing social themes. Cuts to care have affected the care homes, for instance, and as a new resident in such a place, it’s not easy to reconcile yourself with the idea that it’s your final abode. You also have to be lucky to come across a carer who, despite the limited time he has for each patient, tries to make the best of it.

In one of the most beautiful scenes in the book, Frieda is washed by a male carer. Robben describes in minute detail all the acts that come into it, resulting in a tender scene, despite the awkwardness of such a wash:

He lets me take off what I can manage: my underwear, the nappy. And I let him help when it saves us time, like pulling my nightdress over my head once I’ve yanked it up. He turns on the tap and hands me the shower head as soon as it’s warm so I don’t cool off. I take my place in the plastic chair and point the spray at my chest so the water runs down my front and I can pee without much of a fuss.

With Afterlight, Robben once again shows himself to be one of the most subtle novelists in the Dutch-speaking world.

Jaap Robben, Afterlight, translated from the Dutch by David Doherty, World Editions, New York, 2023, 354 p.

For the translation of his third novel, Jaap Robben again called on David Doherty, who won the 2021 Vondel Prize for the translation of Robben’s previous novel Summer Brother.

Doherty also translated Robben’s other books Biography of a Fly

(2021) and You Have Me to Love (2015).