James Ensor and the Happy Entry Into the Brothel

The eccentric nineteenth-century painter James Ensor never married. He was discreet about his private life, giving very little away. Augusta Boogaerts, alias ‘the siren’, was his chosen life partner, but they never lived together. Whether the painter visited brothels for his personal needs is uncertain, but he did frequent them. In the artistic imagination, images and stories about prostitution have rarely been as prominent as in the late nineteenth century.

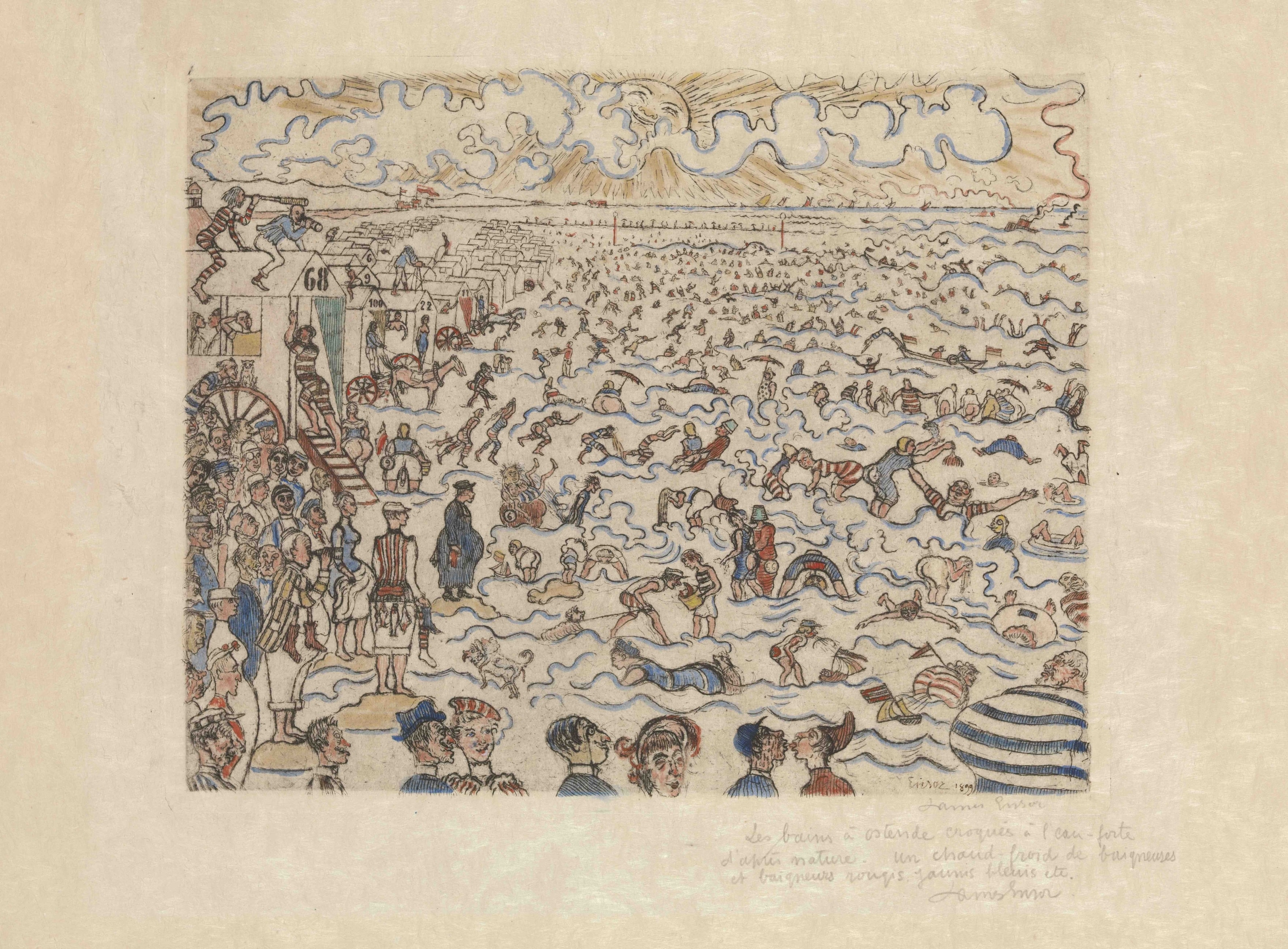

One of Ensor’s masterpieces is The Baths at Ostend, a hefty 1890 ‘cartoon’ picturing dozens of figures frolicking in the sea. A work of sharp social satire, it also provides an insight into the avid eye of the artist, how he looked at the world. On the right of the image, you see bathers in the waves. “A grotesque water ballet and an erotic choreography of bodies in striped swimming costumes that leave little to the imagination,” writes Ensor’s biographer Eric Min.

James Ensor, ‘The Baths at Ostend’, 1890

James Ensor, ‘The Baths at Ostend’, 1890© MSK Gent

“The artist has sketched a catalogue of copious Flemish horniness, with a French-kissing couple, copulating dogs, a woman who capsizes a sailboat with her fart, a lifeguard petting a lady, a puking girl, bobbing beer bellies and bare buttocks. (…) Barely sublimated sodomy and oral sex.” According to Min, this work is a horny variation on Pieter Bruegel’s Children’s Games: a tableau vivant with dozens of extras, an inventory of human impotence. A secret code is hidden in the numbers of the bathing huts. In cubicle 22, a sex worker displays her breasts. Number 69 – ‘head and cow’ in Ostend dialect – has been painted over to read 68.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the public found the work shocking. According to a story told by Ensor himself, the drawing was taken down at an exhibition in Brussels. When King Leopold II visited the show, Ensor told him that he had had to remove it. The king requested to see the work, upon which the monarch–not averse to female beauty himself–is said to have asked the organiser of the exhibition to hang The Baths in a conspicuous spot from there on…

Naturalism and symbolism

The Baths is an amusing and cynical look at bathing culture in the late nineteenth century. Ensor is criticising rank, position, and the prevailing prudishness of society. At the same time, he was not afraid to portray himself as a voyeur. With binoculars, he sits on the roof of bathing cart 68 and watches the scene. “He was an observer, which is saying something,” considers Diane De Keyzer, author of a recently published history of prostitution in Belgian cities. Interestingly, artists were frequent visitors to brothels, including Ensor.

The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are a rewarding period for historians to study prostitution. In cities, an entire administration was developed to regulate the sector. For a historical overview of prostitution in Belgium that a trio of academics published last year, the historian Pieter Vanhees drew on it extensively. “The nineteenth-century sex worker was at the crossroads of medical and legal discussions, scientific research, the struggle for morals and individual freedoms, press articles on scandals, guides to nightlife and feminist texts and pamphlets.”

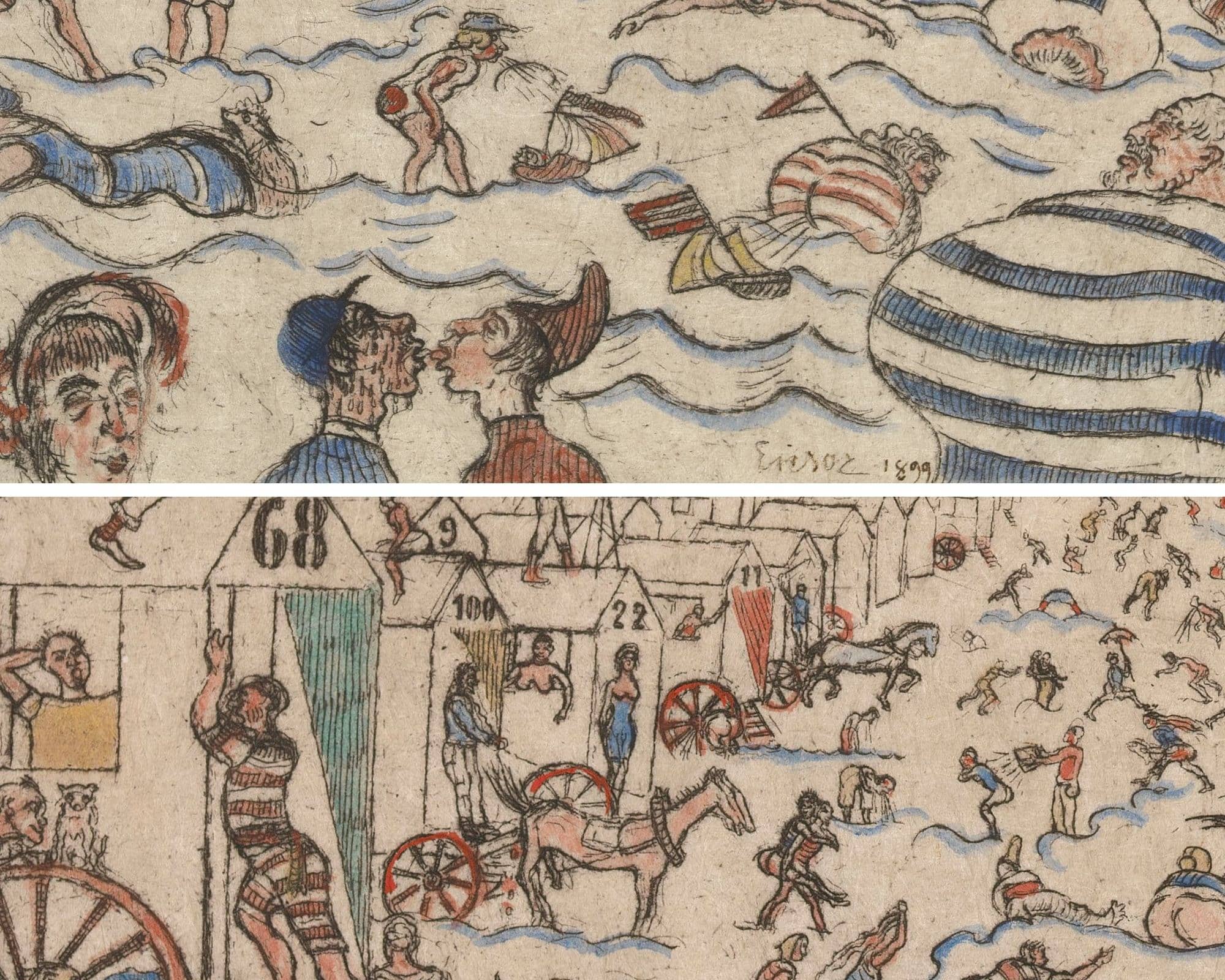

Details of 'The Baths at Ostend'

Details of 'The Baths at Ostend'© MSK Gent

“A final type of source, which tells us about the place the prostitute occupied in the imaginations of contemporaries, is art and literature. French naturalism and symbolism influenced Belgian writers such as Max Elskamp and Georges Eekhoud. Félicien Rops frequently linked prostitution to venereal disease and death in his graphic work. German expressionist Otto Dix depicted the world of prostitution during the First World War.”

Avid eyes

In Antwerp, a haunt favoured by artists was the Cristal Palace: the brothel of brothels, known far beyond the country’s borders. Rops visited often, as did Kurt Peiser and foreign artists such as Eugène Delacroix, William Turner and Dix. “Dix painted Erinnerung an die Spiegelsäle von Brüssel in 1920, but I am convinced that it is about the Cristal Palace,” reasons Diane De Keyzer. “The opulent interior consisted of large mirrors in oriental carved frames, which allowed guests to view the girls of all nationalities from all sides. There were rooms on the upper floors.”

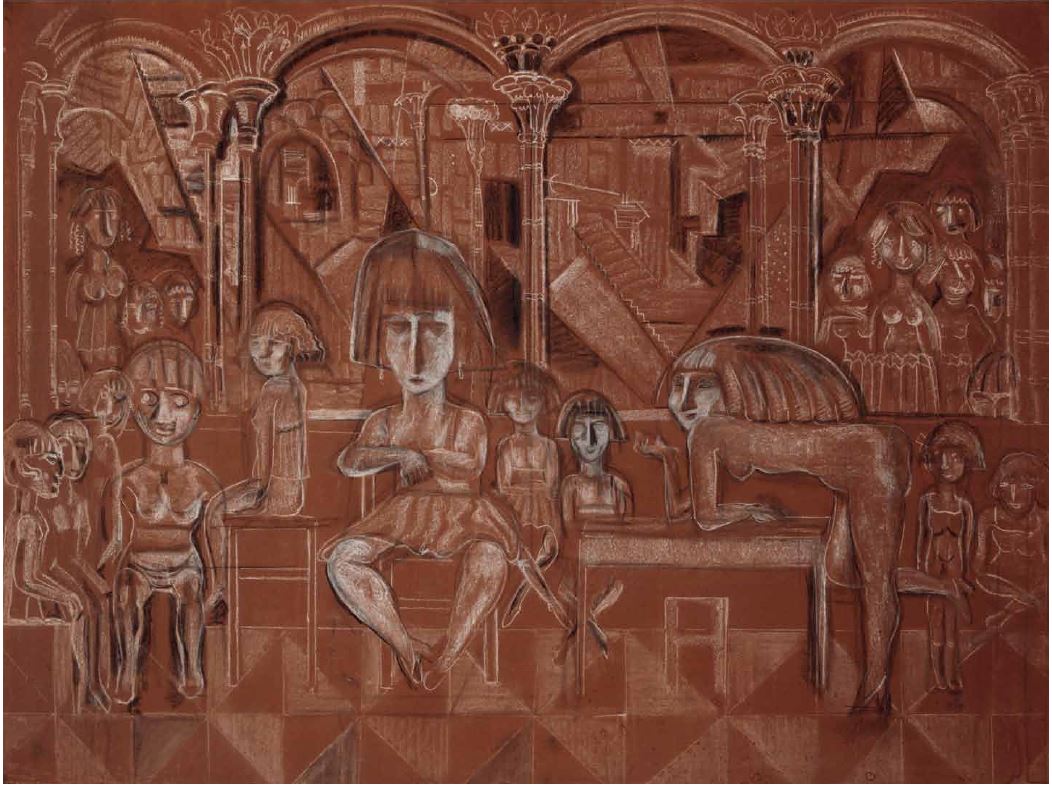

André Favory, ‘Le Cristal Palace à Anvers’, 1922

André Favory, ‘Le Cristal Palace à Anvers’, 1922© RVDV

There is scarce surviving visual material of the interior. One exception is the pen drawing In de glazen kas (The Glasshouse) by Rik Wouters. He made the sketch after the opening of the Kunst van Heden salon, which was dominated by Ensor and several young painters who would later achieve great fame, such as Gustave De Smet, Floris Jespers, Constant Permeke and Jean Brusselmans. Ensor met Wouters that evening and promised to pose for a bust for him. The day could not get any better, the night was young, and afterwards the pair headed for the house of glass in artistic company.

French painter Simon Lévy recorded the event in a letter. “We went to the brothel together where I had a good laugh at Ensor with his umbrella and MacFarlane between two naked women. There were the skinny ones and the fat ones, one of whom Oleffe was lustily fondling. Ensor looked on avidly, because he was entirely disgusted by his two monkeys, one of whom had red hair. And despite his excitement, he sat there very calmly, with his hands on the handle of his umbrella, just like an old peasant. It was actually very clean in colour and very typical. Van Gogh was quite right in his enthusiasm for brothels.”

Vincent van Gogh, 'Head of a Prostitute', 1885

Vincent van Gogh, 'Head of a Prostitute', 1885© Van Gogh Museum

Lévy alluded to Vincent van Gogh’s stay in Antwerp around 1885. The Dutch artist briefly studied at the Academy there and roamed the city in search of models, hoping to establish himself as a modern painter of contemporary city life. He was particularly interested in the working class, including women. “He painted the beautiful Head of a Prostitute in Antwerp, where he also underwent treatment for syphilis,” writes De Keyzer.

Looking for models

“Antwerp has always had a reputation as a city that welcomed everyone regardless of their rank, race or status. That has a lot to do with the port as an economic engine. If things were going well somewhere, artists would flock to it,” De Keyzer explains. “Bredero and Constantijn Huygens were inspired by Antwerp’s red-light district in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It is incredible just how many painters chose prostitutes as their subject. That started after the Renaissance with Adriaen Brouwer, Jan Steen and Hieronymus Bosch. They were artists, but also moral knights. The bourgeoisie happily acquired their work with images of what was forbidden, a bit hypocritically of course.”

“Artists needed models to pose for them, often these were their lovers or mistresses. You are then on the edge of prostitution. What role were they paid for? Take Victorine Meurent, Edouard Manet’s model, who posed nude for Olympia as well as Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass). Both works caused quite a stir, and the model ended up in that negative stream. She was paid for her posing, but whether she provided any other services is unclear. In any case, she lived to be 83 and never contracted syphilis; Manet died at 51 of venereal disease – a veritable epidemic among nineteenth-century artists. Meurent also posed for Edgar Degas, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Alfred Stevens.”

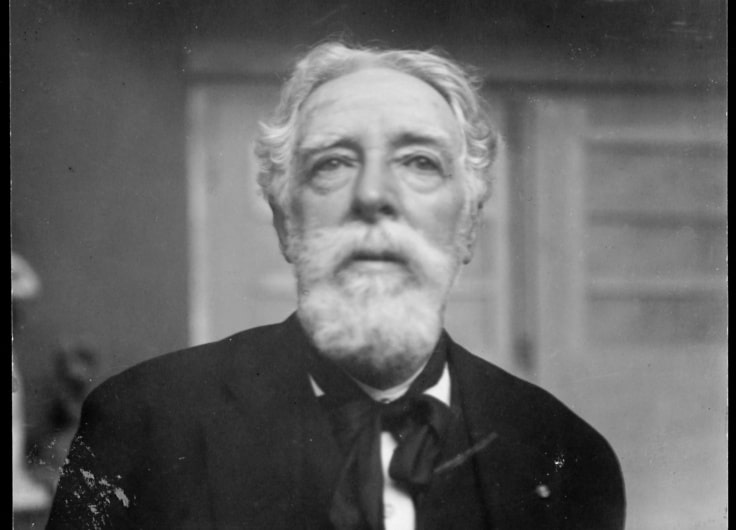

Diane De Keyzer: 'The bourgeoisie happily acquired work with images of what was forbidden, a bit hypocritically of course'

Diane De Keyzer: 'The bourgeoisie happily acquired work with images of what was forbidden, a bit hypocritically of course'© Marc Cauwenbergh

“In the second half of the nineteenth century, many French artists emigrated to freer Belgium. Many settled in Brussels, but they also visited Antwerp. They wanted to see the churches and art treasures, especially the work of Pieter Paul Rubens. After a whole day spent looking at his voluptuous women, they were in the mood for more in the evening. True or not, it is known that Victor Hugo’s sons, Alexandre Dumas, Félix Nadar, the brothers Edmond and Jules de Goncourt and Charles Baudelaire, among others, ended up in the red-light district.”

“At that time it was concentrated in the oldest part of the city around Het Steen, a neighbourhood called the Rietdijk. It had a dubious reputation with numerous brothels or maisons de tolérance, some very common, others especially luxurious. There was something for everyone,” says De Keyzer. “The Palais des Fleurs offers fiery southerners, yes even temple dancers from the Far East, voluptuous Creoles, volcanic mulattoes, enchanting quadroons and capricious negresses (sic),” the French-speaking Flemish writer Georges Eekhoud would later reminisce, when the Rietdijk had disappeared and the red-light district had been relocated.

A rite of passage

“Félicien Rops was also a frequent visitor to le Riddeck (a corruption of Rietdijk, ed.),” De Keyzer continues. “In Antwerp, he could escape provincial Namur in the wake of his French soulmates. I think he is our Toulouse-Lautrec. In any case, he must have known the place well; among other things, he portrayed the book-wives. These are the official prostitutes who were obliged to keep a carnet, a book. In any case, they had to comply with strict rules, such as registration with the civil administration and regular medical examinations. Rops painted such a gynaecological examination, just like Toulouse-Lautrec did in Paris.”

Félicien Rops, ‘Speculum’, 1880

Félicien Rops, ‘Speculum’, 1880© Musée Félicien Rops

“Rops painted countless women, from normal to pornographic. One is often quick to think of a prostitute as a young girl, but that is not quite right. Very young girls were rather more the exception. Older women occupied an important place. Visiting a prostitute was a status symbol. For young men, it was part of their education, just like a grand tour of Europe. They needed to gain experience before marriage, but brides had to be virgins. Hence, they chose a woman who knew the trade.”

“Visiting a brothel was a rite of passage. In the nineteenth century, this practice was also common among the crowned heads of Europe. Brothels were available at all expenses. It didn’t have to cost a fortune. Of course, you had to take care of a courtesan or a concubine. That wasn’t a cheap business, and it still isn’t. Not much has changed in five hundred years, partly because prostitution takes place in a legal twilight zone,” De Keyzer estimates.

Old scoundrels

“In a brothel, the aim is still to get customers drunk, to have them pay for as many drinks as possible. Consuming is more important than taking customers to bed,” De Keyzer writes. “That could also be the reason why Ensor went to the whores with Wouters, just to have a pint together. I suspect Wouters would have gotten quite some flak from his wife and model Nel had he gone there for the girls.”

“Whether Ensor paid for sex, we may never know. He must have been familiar with the prostitution milieu: he spent his youth in the vicinity of Kleine Weststraat, Ostend’s red-light district. And it would not surprise me if, as a young man, he too underwent some kind of rite of passage, but of course that remains a question mark,” De Keyzer concludes.

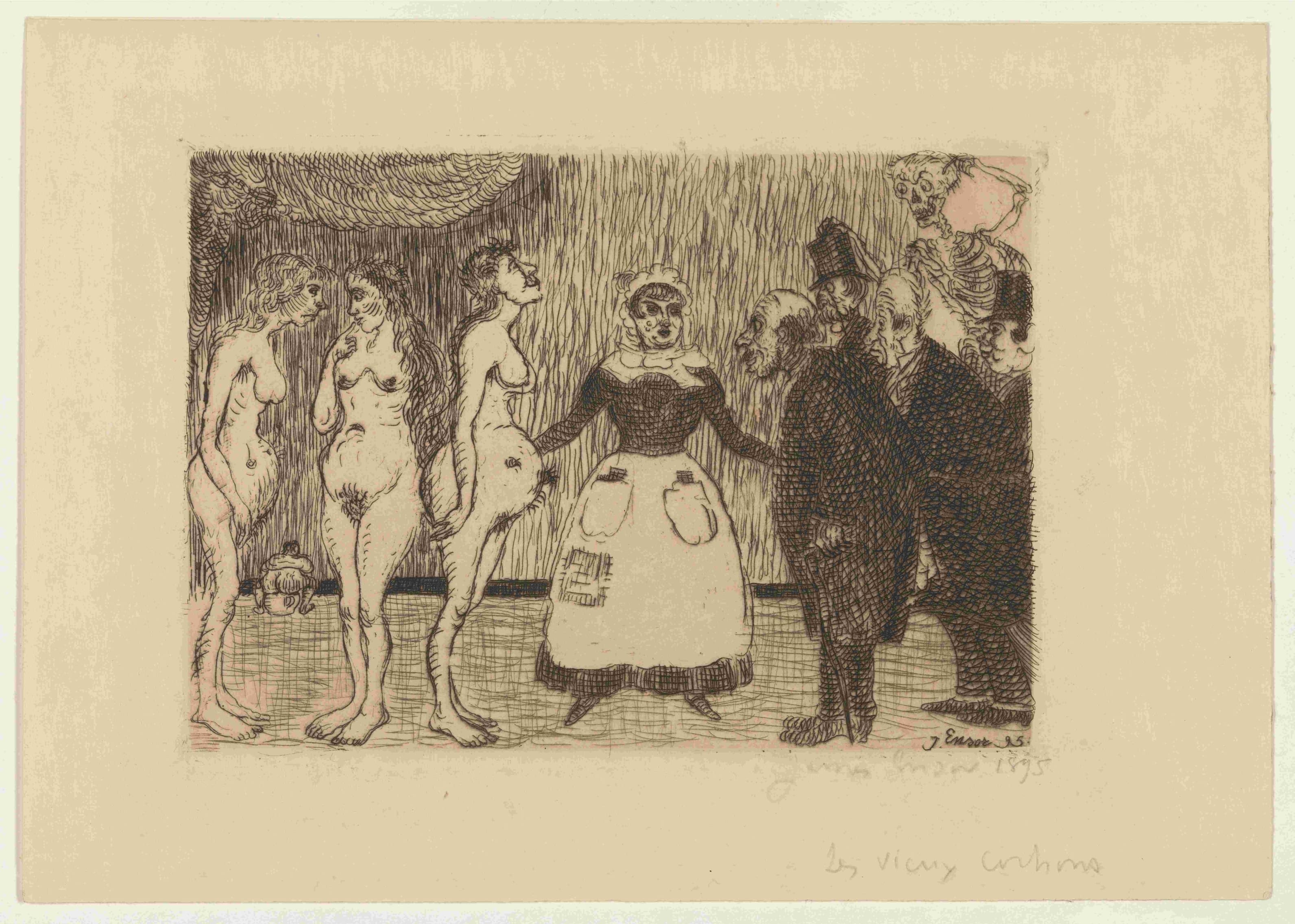

The artist was often an observer rather than a participant. In his work, Ensor repeatedly chose the fringes of society as his subject matter. In the etching De Oude Schelmen (The Old Scoundrels), he openly poked fun at the hypocrisy of contemporary bourgeois morality. What he thought about the figures is also evident from the different titles he gave: Old Pigs, The Doctors’ Visit, Members of the Academy Looking for Modern Beauty.

James Ensor 'The Old Scoundrels ', 1893

James Ensor 'The Old Scoundrels ', 1893© MSK Gent

Glass case shattered

Ensor, Van Gogh, Dix, Wouters, Paul van Ostaijen… a long parade of famous artists passed through the Cristal Palace. It existed until 1968, when the building collapsed ingloriously. A bouncer was able to save the Spanish owner, his wife and two barmaids from under the rubble, but two nude dancers and a drummer were killed. Today, there is no trace of the legendary brothel.

Antwerp art dealer Ronny Van de Velde has caught the bug for the neighbourhood’s history. A few years ago, he found André Favory’s 1920s painting Le Cristal Palace à Anvers. Like his compatriots many decades earlier, the Frenchman had come to Antwerp to study Rubens. His women are Rubensian, but the interior with its mirrors and mosaic floor seems realistic. They correspond with the work of Antwerp artist and ladies’ man Paul Joostens. He too captured impressions of the Cristal Palace.

Paul Joostens, ‘Cristal Palace’, 1924

Paul Joostens, ‘Cristal Palace’, 1924© Paul Joostens

Thanks to some later photographs taken at the Cristal Palace, we know that the paintings by Favory and Joostens are not utter fantasy. On 18 December 1959, the poets Paul Snoek and Hugues C. Pernath rented the establishment to host a presentation of their collections of poems. “The morbid, unexpected location was ideal for doing something completely absurd, shocking and unique,” Snoek noted in his biographical novel Een hondsdolle tijd (A Rabid Time, 1978), in which he recounted juicy details about the place. The heyday of the brothel of brothels was long gone by then.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.