James Ensor, Rebel For All Times

James Ensor was not just a crazy, angry, solitary painter of masks, he was also an authentic rebel who spent a lifetime using his voice as a person and as an artist to champion values that still hold true today, with his eye for beauty, for nature, for heritage and for the imagination of art.

Today, in standard works on art history, James Ensor (1860-1949) is considered to be a form innovator and premodernist who is mentioned in the same breath as Van Gogh, Munch and Cézanne. But in the interwar period, Ensor was still mainly regarded as an artist’s artist. Which other artist can say that colleagues of the calibre of Wassily Kandinsky, Emil Nolde, Maurice De Vlaminck and many others made the long train journey to Ostend to meet him in his studio, as if it were a pilgrimage?

James Ensor

James Ensor© KMSKA, Antwerp

After Ensor’s departure from earthly existence, his art fared even better. In recent decades the wider public has embraced Ensor too. Not so long ago there were retrospective exhibitions at the MOMA in New York, the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in London and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. In addition, Ensor year – much anticipated in the media – began in December 2023, marking the seventy-fifth anniversary of his death with an extensive programme in Ostend (his home city) and Antwerp (the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp houses the largest collection of Ensor’s work in the world).

In short, he should and will be celebrated.

Antibourgeois nature

Once upon a time that was different. At the height of his artistic ability, roughly between 1880 and 1900, attention to his originality was inversely proportional to his considerable self-confidence. In other words, with the exception of a few bright spots, audiences and critics did not follow. Ensor found himself on the margins of the art world. This was due not only to his peripheral location (Ostend was a provincial city) and his contrarian nature, but also undoubtedly to what his contemporaries felt was his overly visionary view.

Ensor's visionary mind shone not only on the state of painting, but also on issues that are still current in society today

In Ensor’s aesthetics, rules and styles were intertwined, regardless of the dominant trends. He invented his own artistic paradigm, as a one-man movement. However, his visionary mind shone not only on the state of painting, but also on issues that are still current in society today. Ensor did not shy away from social criticism but was all too keen to dissect the class society. Even in his later years – from his fifties to old age – he would remain socially engaged, even after he was knighted and became a baron, in 1929. Detractors claim that he renounced his antibourgeois nature then. But his vitriolic pamphlets and speeches prove the contrary. He spoke out vehemently against vivisection in a period when belief in rational science was sacred. He advocated the preservation of historic buildings from the late Middle Ages when modernism was already the order of the day – “away with that rubbish”. And, as a dyed-in-the-wool environmentalist avant la lettre,

Ensor condemned the building over of Belgium’s dune belt.

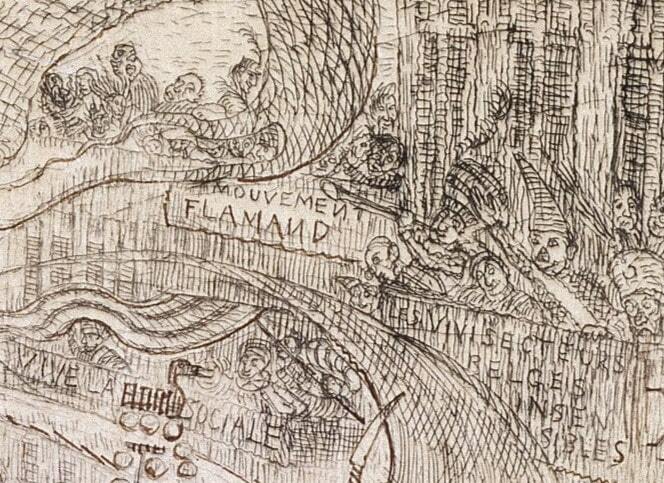

The slogan Les vivisecteurs belges insensibles, detail from the print Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 (copy of the painting of the same name). In the late nineteenth century already, Ensor spoke out against vivisection and for the protection of animals.

The slogan Les vivisecteurs belges insensibles, detail from the print Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 (copy of the painting of the same name). In the late nineteenth century already, Ensor spoke out against vivisection and for the protection of animals.© MSK Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent / Dominique Provost

Once a rebel, always a rebel. But that aspect has been snowed under in the steadily growing secondary literature. The one-sided image of a solitary, contrary narcissist in his first and “best” period is easier to sell than the image of an elderly, tarted-up “baron” who is still a real rebel at heart.

Bold and wanton Ostend

So Ensor rebelled. But what was the climate that produced this rebel? Besides his characteristic gift of nature, his environment and his professional experiences also played a role.

To begin with, James Ensor’s home situation as an adolescent was not exactly rosy, with a domineering shopkeeper mother who did not believe in her son’s “little pictures”, especially after she counted the pennies they brought in. His father was a down-at-heel English intellectual who did not prosper in the folksy, rough environment in which he had ended up. The young Ensor saw mainly marital squabbles and a father who drank himself to death. He was so disgusted that he limited his love life to platonic or non-public experiences.

Once a rebel, always a rebel. But that aspect has been snowed under in the steadily growing secondary literature. The one-sided image of a solitary, contrary narcissist in his first and “best” period is easier to sell

At home with his mother and grandmother – they both had souvenir shops – there were two things he certainly picked up: a fascination for (carnival) masks and the acerbic Ostend dialect. It seems the sometimes blunt, “indelicate” slogans in his caricatures and his brutal self-mockery stem straight from the Ostend nature. After spending a few weeks in Ostend, the writer Jeroen Olyslaegers once referred to it as “bold and wanton”. Coastal people just are not and were not known for their indulgence, but for their straightforward attitude.

What a contrast there must have been between the poor, rough fishing quarter with its public fish market – the Vistrap – and the chic promenade just a few hundred metres away. During the Belle Époque,

all the royals, including the Shah of Persia, used to parade on the promenade. Yet it was just a proverbial stone’s throw from his parental home, which was fifty metres from the sea and the beach. These contrasts must have caused conflict as well as anger in his social thinking.

Scabrous captions

So how did this rebelliousness creep into his art? For there, too, Ensor was a rebel. When he was still in his early twenties, his name was already being mentioned as a promising painter and in 1883 he joined Les XX, the avant-garde circle that sought to provide an answer to Impressionism. Although initially he was a spokesperson, he increasingly had to put up with his works being rejected, resulting in a chronically empty purse. His masterpiece, the monumental Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, was refused for the Les XX salon in Brussels, while pointillist Georges Seurat’s An Afternoon on the Island of la Grande Jatte (1886) was given a place of honour. Ensor did not refrain from denouncing Seurat’s picture of ladies and gentlemen of standing beside the Seine in pointillist style as bourgeois art.

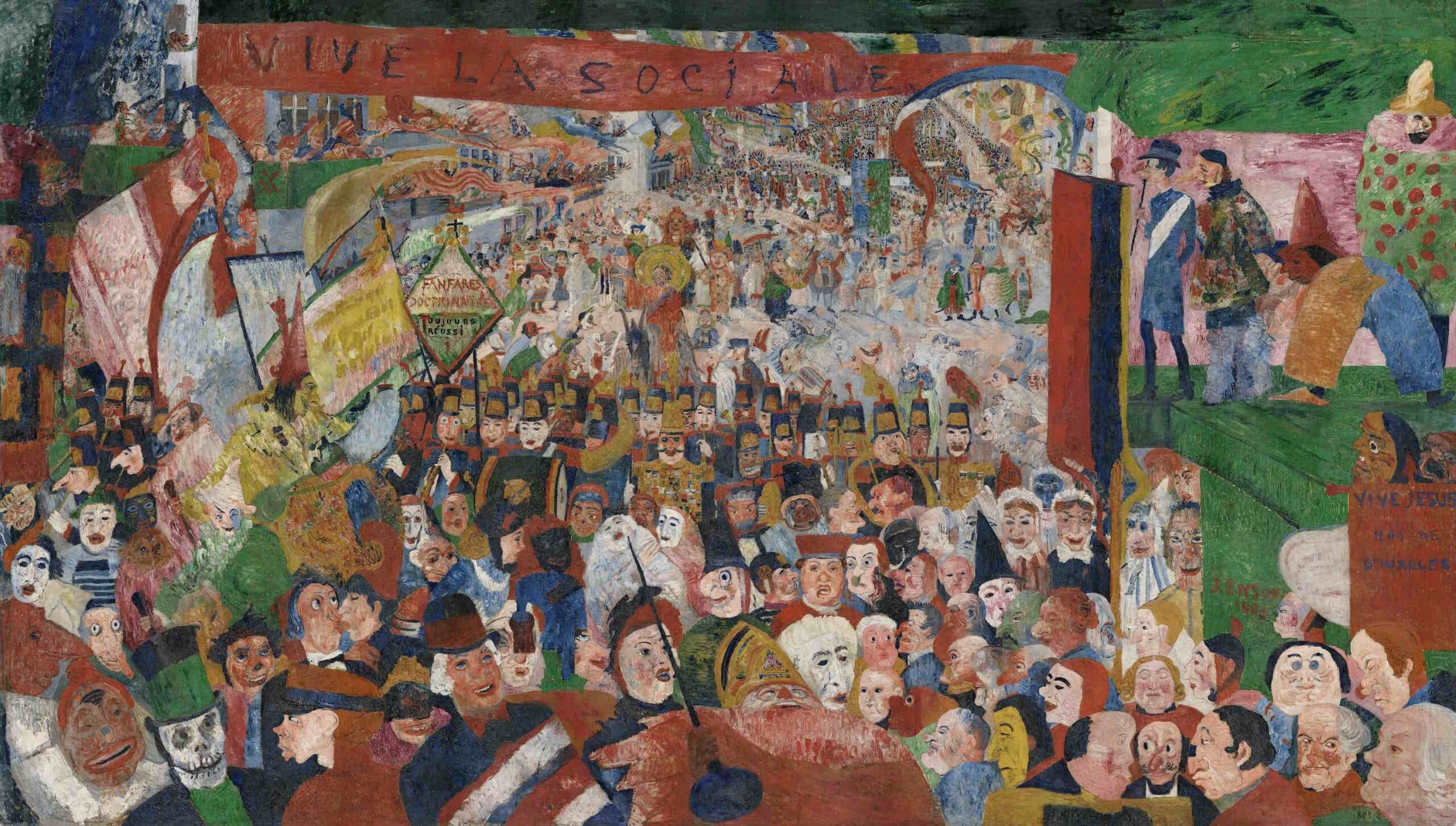

Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, 1888, with the slogan Long Live the Social

Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, 1888, with the slogan Long Live the Social© J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Another of Ensor’s works, The Baths at Ostend, was on view at the La Libre Esthétique salon in 1891, but only in a back room with a curtain in front of it. Both of his key works had scabrous captions and depicted scenes that critics felt should preferably not see the light of day.

Out of frustration and fascination, Ensor had already started a new style in both palette and theme. He started to touch up his early “academic” works with masks. A black man in loincloth with a parrot on a staff, from 1877, was joined thirteen years later by astonished mask faces peeking at him. He also resolutely added a flowery hat to his self-portrait, an obvious analogy to the great Rubens.

Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat, 1883-1888, an analogy to Rubens, an act of travesty and self-affirmation

Self-Portrait with Flowered Hat, 1883-1888, an analogy to Rubens, an act of travesty and self-affirmation© Mu.ZEE, Oostende

It was an act both of travesty and of self-affirmation. He was claiming his own place in the history of art. Ensor sought sublimation for a world that left him despairing. The prevailing form language was inadequate for what he thought about and saw in the world. In masks, travesty and skeletons he did find adequate images. Masks hide who you are, but also reveal who you want to be. Ensor’s theme is at the level of the existential, not the carnivalesque. In his new style, he wrapped up his disillusionment with people and the contemporary art world.

Enter the pictorial rebel and the famous peintre de masques – the painter of masks – as he was known unequivocally for a long time. Exit his chances of painting fame in the short term. What at the time received most criticism as being nonsensical, critics would later refer to as Ensor’s trademark.

Ensor was angry

But Ensor’s oeuvre is of course much richer than the masks. He was able to switch styles, genres and angles because, as a good postmodernist avant la lettre, he felt he had the right to be inconsistent. In parallel with the surreal-symbolic use of masks, a significant part of his production is overtly socially critical, because Ensor was angry. His cartoon Doctrinal Nourishment, 1889, is iconic in this respect. The three establishment groups of the time – the nobility, the clergy and the army – defecate on the people who feast on their excrement.

Doctrinal Nourishment, 1889. The nobility, the clergy and the army defecate on the people, who feast on their excrement

Doctrinal Nourishment, 1889. The nobility, the clergy and the army defecate on the people, who feast on their excrement© MSK Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

The Entry, a wall-to-wall scene depicting a supposedly religious parade, actually shows a cross-section of the working population and is peppered with slogans and salient details. The banner Vive la Sociale, in which Ensor makes a deliberate linguistic mistake, dominates. The feminisation of the masculine le social, is a clear reference to Vive la République sociale – Long Live the Social Republic – a slogan used during the Paris Commune.

At a time when emerging socialism was the number one enemy of the Church and capital (and their party-political counterparts), this was a message that could not be misunderstood. It is also striking that the central Christ figure is depicted tiny on a donkey and is mocked or ignored, although he is the very reason for the procession. This is not the only time that Ensor identified on his canvases with the Christ figure, who means well but is not understood.

As a good postmodernist avant la lettre, Ensor felt he had the right to be inconsistent

Other good examples of his zeal for social justice can be seen in The Strike (1888) and The Gendarmes (1892). When the starving and desperate fishing community came out on the streets, the gendarmerie shot a couple of fishermen dead. The establishment did nothing. Ensor was outraged and reached for his paintbrush.

Few contemporaries imitated him in this sort of indictment, and certainly not as explicitly and cockily brilliantly. Quel culot! How cheeky! Another fine example of Ensor’s commitment and animosity is The Bad Doctors (1895). In those days quacks were the problem, now we call it overmedicalisation.

The Gendarmes (1892) is a good example of Ensor’s zeal for social justice

The Gendarmes (1892) is a good example of Ensor’s zeal for social justice© Mu.ZEE, Ostend

Reason is the enemy of art

At the end of the nineteenth century, the painter was already speaking out against vivisection and for the protection of animals. He would continue to do so with a few supporters, well into his old age, until a minimum of legislation had been voted in the Belgian parliament. As a child, he had seen how draught dogs were abused to the point of drawing blood, as were the donkeys that brought the famous bathing carts (wooden changing huts on wheels) to the tide line. He lashed out in his works and in his speeches. The slogan Les Belges vivisecteurs insensibles (Belgians – insensitive vivisectors) appears in a variety of grotesque scenes. As a baron, he used his voice at chic banquets to lecture the establishment. Whether it was the members of the Royal Academy of Belgium who were offering him a banquet (for his birthday perhaps, or something else), a gathering of judges and consuls, or the mayor or other important people from the Cercle Littoral, he invariably raised his voice:

I have sworn to fight against the frenzy of vivisection and its malpractices. Any occasion is good, even our wonderful and touching banquet. So I shall seize this opportunity with both hands and will be brief and to the point.

This salutation leaves little to the imagination, and Ensor followed it up with an exposé in which he took, among others, the French Enlightenment philosopher Descartes to task, because his positivistic discourse had given license to such crimes by putting science above human values. “Reason is the enemy of art”, said Ensor, and in another speech, “Descartes’s unhealthy doctrines are intended to sterilise the human heart in the name of pure reason.”

Is it unreasonable to argue that in 2023 we are still in an anthropocentric discourse that puts humans above animals and planets with all the dramatic consequences that entails?

Few contemporaries imitated him in this sort of indictment, and certainly not as explicitly and cockily brilliantly

Another of Ensor’s pet peeves is the preservation of nature and heritage. In his inimitably creative use of language he denounced the hypocrisy of the system, which he accused, with a self-styled neologism, of des crimes de lèse-beauté – crimes against beauty – or, better, defamation of beauty, just as there is defamation of the king or the police. It was of that order, he felt. He also stood up for the preservation of the dunes, whose charm he praised in essays and speeches which he collected in Mes écrits (My writings). “Let us protest from Ostend to Blankenberge, because the virginity of the dunes is being eroded”, he argued in ‘La Beauté Menacée: les Dunes’ (1921, Beauty under threat: the dunes). Meanwhile, large stretches of Belgium’s original coastline have been built up to the detriment of the dune belt, which not only constitutes an exceptional ecological biotope, but also a natural barrier against storms and tides.

In his accusations of crimes against beauty, Ensor also often talked about heritage. He advocated, for example, for the preservation of a Romanesque tower with a spire dating from 1438, the only remnant of the burnt-down Sint-Petruskerk (St Peter’s Church) in Ostend, popularly known as the Peperbusse. He displayed the same activism with regard to a beautiful little church from the fourteenth century, Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-ter-Duinen (Our Lady of the Dunes) in Mariakerke, which he had painted and drawn so often as a young artist. The Ostend city council wanted it demolished for urban expansion in the late nineteenth century, which did not happen in the end. Fifty years later the same city council honoured him with a state funeral, and it was at that very church that he found his last resting place – it poured with rain as his coffin was laid to rest.

View of Mariakerke (1901) with Our Lady of the Dunes Church, where Ensor’s state funeral took place

View of Mariakerke (1901) with Our Lady of the Dunes Church, where Ensor’s state funeral took place© Mu.ZEE, Ostend / Danny de Kievith

Meanwhile, in Ensor’s own city of Ostend, the maritime port on the east bank had been handed over by the city council to two real estate companies to be sold to exclusive buyers. On the western side of the town, a landmark of interbellum architecture, the Thermae Palace Hotel stands on the promenade, flanked by the famous Royal Galleries from the early part of that century. Both of these postcard icons have been in a questionable state for decades. People stand there, look at them and proclaim Ensor year.

Let not only his art, but also his social commitment be a source of inspiration

So, James Ensor was not just a crazy, angry, solitary painter of masks as cliché would have it, he was also an authentic, visionary rebel who spent a lifetime using his voice as a man and as an artist to participate actively in the world. He championed humanist and social values that still hold true today. He had an eye for beauty, for animals, for nature, for heritage and for the imagination of art.

Ensor has already influenced countless artists, but let that other, social commitment, which he expressed in so many ways, be a source of inspiration. Let the rebellious Ensor be a one-man movement for the future.

Works consulted

. James Ensor, Mes écrits, Éditions nationales, 1974. French quotes are freely translated.

. Marcel De Maeyer, ‘De genese van masker-, travestie- en skeletmotieven in het oeuvre van James Ensor’, 1963, in: Various authors, James Ensor, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthaus Zürich, 1983

. Patrick Florizoone, James Ensor over dierenbescherming en vivisektie, self-published, 1994

. Herwig Todts, James Ensor, Occasional Modernist, Brepols, 2019

. Xavier Tricot, James Ensor. Leven en werk. Oeuvrecatalogus van de schilderijen, (James Ensor. Life and Work. The complete paintings) Mercatorfonds, 2009

. Xavier Tricot, James Ensor. The Entry of Christ into Brussels in 1889, Pandora Publishers, Antwerp, 2020