James Joyce’s Summer Holiday in Ostend

On 16 June, James Joyce and his most famous novel Ulysses will be celebrated for the first time in Ostend during Bloomsday. Belgium’s largest coastal town has its own unique connection to the Irish author. In 1926, Joyce spent a summer holiday in Ostend. He wrote letters and postcards to his friends while there, many of which survive, as does an evocative set of photographs. ‘This is by far the best place we have been in for a summer holiday.’

Seeking respite from the summer heat of Paris, James Joyce arrived in Ostend on 5 or 6 August 1926, accompanied by his wife Nora and daughter Lucia. It is not known why Joyce selected Ostend as his summer refuge. Popular since the turn of the century, the Belgian coastal town was a magnet for the European beau monde and other assorted rich and famous characters. Some of the greatest stars of the day performed in the plays, concerts, recitals and operas that were staged at the Casino and Théâtre Royal. Others were drawn to the horse races at the Wellington Hippodrome. The luxury hotels along the promenade were often fully booked. By all accounts, the season of 1926 was a glittering success.

This is what Ostend looked like when Joyce and his family stayed there.

This is what Ostend looked like when Joyce and his family stayed there.© Beeldbank Kusterfgoed

Upon their arrival in the city, James, Nora and Lucia Joyce initially stayed at the Littoral Palace, situated on the corner of the Hertstraat (Deer Street) and the Sea Promenade. For Joyce, the initials of the Auberge Littoral Palace in Ostend corresponded with those of Anna Livia Plurabelle, the female protagonist of Work in Progress, which he had commenced in 1923 and was then still writing. In reality, the hotel was simply called the Littoral Palace, with Joyce adding ‘Auberge’ of his own accord.

By 1926, Joyce had already published extracts of Work in Progress in the Parisian literary magazines Transatlantic Review, Transition and Le Navire d’argent. This is the book that he would eventually publish in 1939 as Finnegans Wake

(Faber and Faber, London and the Viking Press, New York).

James and Nora Joyce with fellow Irishman Patrick J. Hoey in Ostend, August 1926. Collection: University at Buffalo, the State University of New York.

James and Nora Joyce with fellow Irishman Patrick J. Hoey in Ostend, August 1926. Collection: University at Buffalo, the State University of New York.© rr

Joyce has met a fellow Irishman named Patrick Hoey in Ostend. Little is known about Patrick Hoey and his relationship with Joyce. One would expect to find Hoey’s name in the 1926 register of foreign nationals residing in Ostend, together with vital data, but there is no trace of him in the local archives, many of which were destroyed when the Germans bombed the city in May 1940. What can be ascertained, however, is that Patrick Hoey worked as a chemist’s assistant at the Pharmacie anglaise (English Pharmacy) on the corner of Adolf Buyl Street and Marie-José Square in Ostend, which was owned by Albert Bouchery (1858-1941). Joyce expands on his friendship with his compatriot in a subsequent letter to the British activist and the editor of the magazine The Egoist, Harriet Shaw Weaver (1876-1961), which he wrote in Ostend on 18 August 1926:

Mr Patrick Hoey whom I met here behind a chemist’s counter recognised me after an interval of 24 years. He was present at a supper given to me before I went to Paris in 1902. He is a great admirer of my works and pomps and has all the first editions. He is in fact a very good ▽ all the more as his name is the same as my own. Joyeux, Joyes, Joyce (Irish Sheehy or Hoey, the Irish change J into Sh e.g. James Sheumas, John Shaun etc). He very often uses the identical words I put into▽’s mouth at the Euclid lesson before coming down here. [the inverted triangle is one of Joyce’s symbols used in his letters and manuscripts]

Joyce states that his own surname and that of Hoey have the same etymological roots, which leads us to surmise that his brush with Patrick Hoey in Ostend was far from insignificant. It was undoubtedly a chance meeting, although Joyce may well have seen it as a stroke of luck. Could he have viewed the encounter as a kind of ‘epiphany’? Did Joyce view Patrick Hoey as a kind of avatar as a result of their common etymological heritage?

Ostend beach in 1926

Ostend beach in 1926© Beeldbank Kusterfgoed

During his stay in Ostend, Joyce wrote several letters to Sylvia Beach (1887-1962), an American bibliophile, whom he had met in Paris in 1920. Beach was the founder and proprietor of the bookshop Shakespeare & Co., which had opened its doors at 8 rue Dupuytren in November 1919. She has moved her shop to 12 rue de l’Odéon in 1921. Shakespeare & Co. was a nexus for book-lovers and authors, a place where people exchanged ideas and where Sylvia Beach introduced writers to publishers. Her decision to publish Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922, at a time when no other British or American publisher would touch the manuscript for fear of censorship, had made her bookshop famous.

On 11 August, Joyce sent a postcard to Harriet Shaw Weaver telling her that they are ‘here for a few days and are busy enjoying the good air and food and hotel hunting. […] This is by far the best place we have been in for a summer holiday’. By all accounts, the author was enjoying his stay in Ostend but, nevertheless, was still ‘hotel hunting’, in search of a good but cheap hotel. In his postcard, Joyce also mentions Dora Marsden (1882-1960), an English suffragette editor of literary journals, and philosopher of language. She was the publisher of the suffragist magazine, Freewoman, which eventually became The New Freewoman. The magazine was renamed The Egoist in 1914, and Weaver succeeded Marsden as editor. Through the involvement of Ezra Pound, the publication became associated with modernist literature and published avant-garde writers such as Joyce, T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) and Percy Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957), who was also a well-known painter.

James Joyce: ‘This is by far the best place we have been in for a summer holiday.’

In his letter, dated 18 August, to Harriet Shaw Weaver, Joyce makes reference to the heavy thunderstorm that blew into Ostend on Monday 16 August. He also tells her about the events of the previous day (Tuesday 17 August), namely his walk along the beach from Middelkerke (a small coastal town about 9 kilometres from Ostend, towards De Panne, near the French border) to Mariakerke (a former village on the outskirts of Ostend with a picturesque church, Our-Lady-of-the-Dunes). The churchyard also contains the grave of the celebrated Ostend painter, James Ensor (1860-1949), who was buried there on 23 November 1949.

In his letter, Joyce also mentions Georg Goyert (1884-1966), who translated Ulysses

into German for the Rhein-Verlag publishing house in Basel, and the Franco-German poet Ivan Goll (1891-1950). Goyert probably arrived in Ostend on 28 August where he met Joyce at the Hôtel Helvetia, on the Sea Promenade, and where they worked together on the translation of Ulysses. In a fascinating passage at the end of his letter, Joyce describes an encounter with a little girl. This encounter seems to have been a kind of ‘epiphany’, one that is reminiscent of Saint Augustine’s chance meeting with a child on a beach. Saint Augustine (c. 354-430) is known for his treatise De Trinitate (About the Holy Trinity), the result of a thirty-year period of meditation upon the mystery of the Trinity.

James, Nora and Giorgio Joyce in Ostend, August 1926. Collection: University at Buffalo, the State University of New York.

James, Nora and Giorgio Joyce in Ostend, August 1926. Collection: University at Buffalo, the State University of New York.© rr

On 1 September 1926, Joyce invited his son Giorgio [later: George] to join them in Ostend. In his paternal missive, Joyce not only encourages his son to make radical changes to his life but also to travel to Ostend, where he can enjoy the fresh air from the ocean. He tells him to send a telegram with the date and the hour of his arrival. Although we do not know exactly when Giorgio arrived in Ostend, it could not have been prior to 4 September. On 13 September, Joyce sent a telegram to Sylvia Beach, in which he announces his departure for Ghent. The Joyce family continued their travel throughout several Belgian cities.

Joyce, who was a good Latinist, must have realised that the name ‘Ostend’ means different things in different languages. The Dutch name for the city, ‘Oostende’, translates as ‘at the east end’: a reference to the city’s medieval location on the eastern tip of the peninsula known as Testerep (or Ter Streep), now subsumed by the sea. The French spelling for the city is ‘Ostende’. In Latin, however, ostende

is the present singular imperative of the verb ostendere, which means ‘to show’. It is perhaps worth noting that Joyce used the form ostenditur (third singular passive indicative of ostendere) in Finnegans Wake. Joyce’s use of the neologism ‘ostscent’ in Finnegans Wake is also a plausible reference to the city of Ostend and to the famous summer storm of 16 August.

16 June is Bloomsday in Ostend. To celebrate Ulysses’ centenary, the brand-new Joyce Committee is organising the free public programme ‘The Doormen of the Ocean’, with a publication, an exhibition and an animated walk.

More information on www.ostendiana.be.

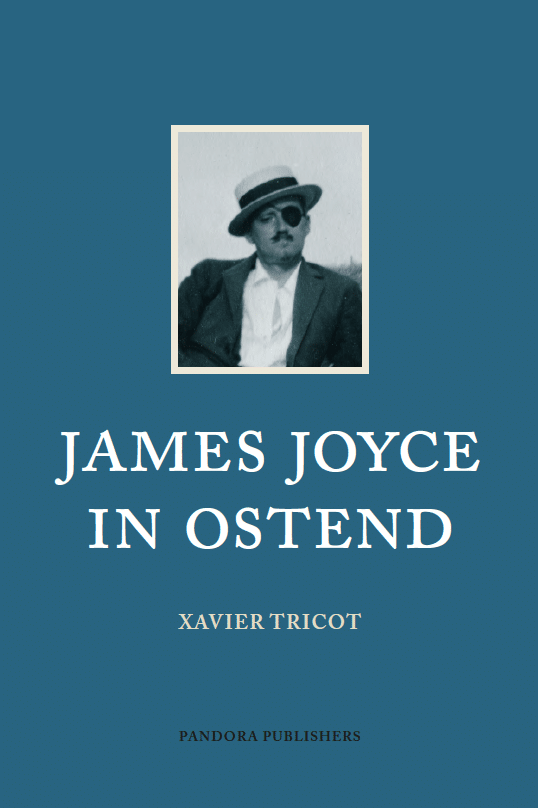

The author of this article, Xavier Tricot, wrote a detailed account of the author’s stay in the Belgian coastal town, including an album of photographs taken at Ostend during the summer of 1926: James Joyce in Ostend, Antwerp, Pandora Publishers, 2020, 92 pp.