Jef Last: A Life of Commitment in the Twentieth Century

The life of Jef Last (1898-1972) offers a splendid introduction to the twentieth century, as is apparent from a new biography of this committed Dutch writer. From the Spanish Civil War to the struggle for independence in Indonesia, and from the conflict between Communist ideal and Soviet reality to the battle for gay rights in the Netherlands.

As early as his school leaving certificate year Jef Last had opted to dedicate his life to the creation of a more just society. On all levels of society and via various political parties he committed himself to this end, until he realised that he was most useful as an unaffiliated writer and intellectual. Through his talent as a speaker, writer and organiser, and through his knowledge of languages – he spoke fourteen – he was able to build a network that extended into the highest international regions as is evidenced by such resonant names as Sukarno, Malraux, Camus, Gorki, Ivens, Gide, Brecht and Pasternak.

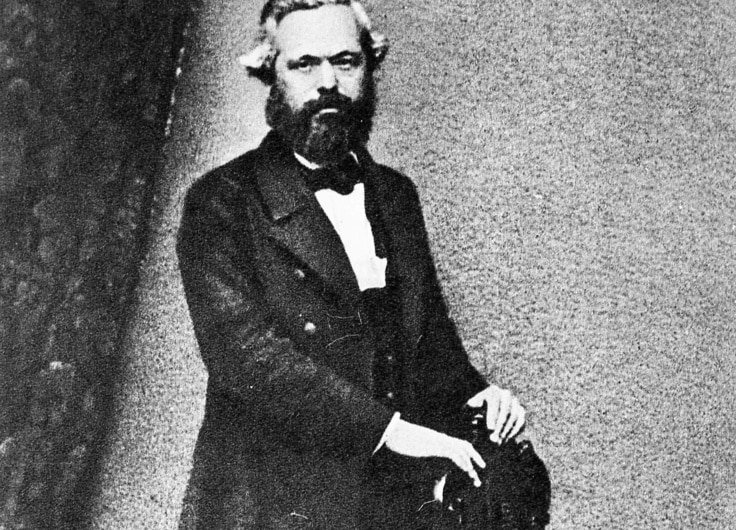

Jef Last

Jef Last© Museum of Literature, The Hague

At an early age Jef Last joins the Social-Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP) and out of conviction combines a university study of Chinese with work as a fisherman, agricultural labourer and miner. Although ‘male love’ attracts him, he marries Ida ter Haar, like himself from a wealthy family with an Indies background. They share radical solidarity with the working class and the proletariat and set to work as paid officials of the SDAP responsible for youth work and culture.

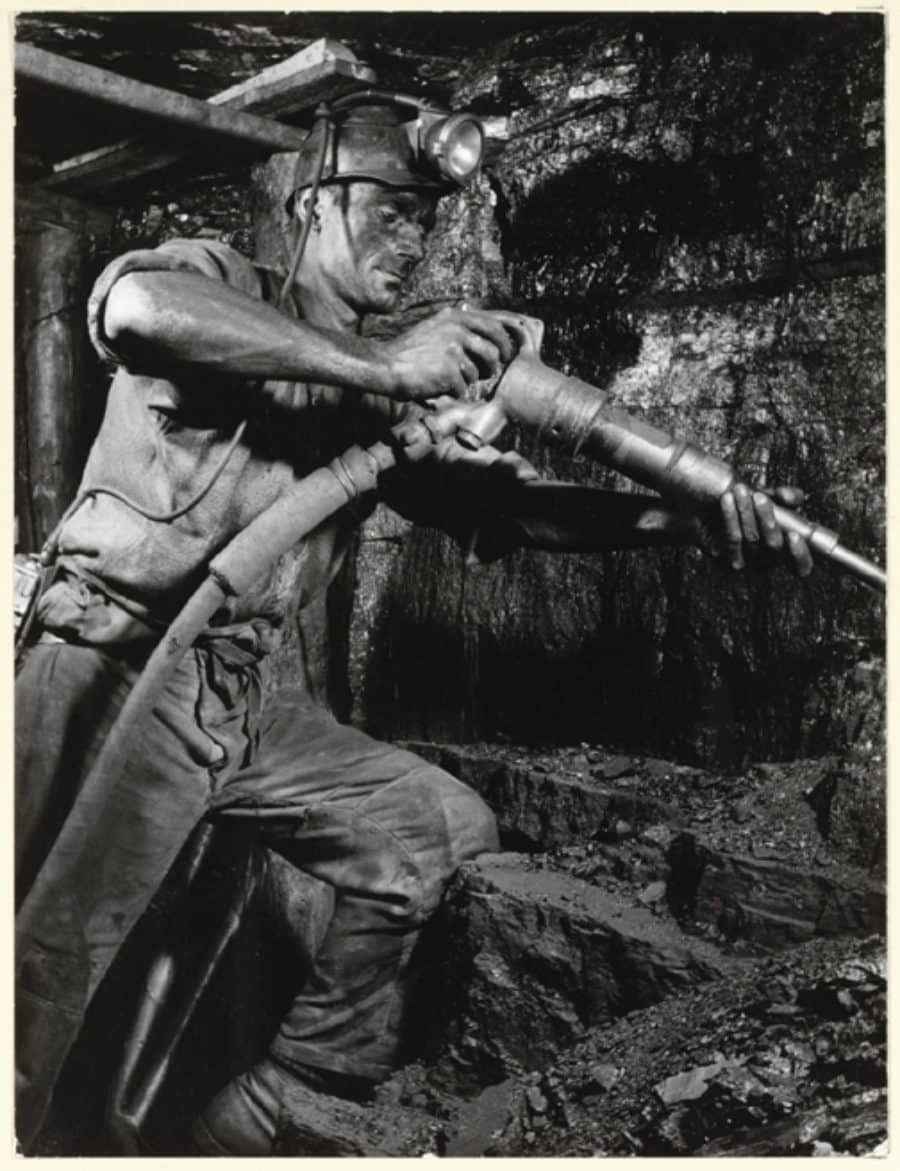

Jef Last working as a miner

Jef Last working as a miner© Museum of Literature, The Hague

In around 1926 Jef publishes collections of revolutionary songs and tours the provinces in a converted car showing experimental films. He is active in the struggle against colonial oppression in the Netherlands Indies and in that context writes passionate agitprop poems. In 1930 he parts company with the SDAP because the latter had come out against the independence struggle of the Indonesians.

Jef Last operates as an independent publicist and journalist in the service of the world revolution

For a number of years he operates as an independent publicist and journalist in the service of the world revolution. When in 1931 he writes a reportage on the Soviet Union, he gets to know inspiring writers such as Gorki and Aragon, but regards the Soviet Union with mixed feelings. Nevertheless, like many other intellectuals, he sees Communism as the only possible weapon against the advance of fascism. Consequently, his biographer Rudi Wester sees the fact that in 1933, the year that Hitler comes to power, Last becomes an official member of the Communist Party of the Netherlands (CPN), as a strategic step. She sees the split between his publications and letters. He no longer preaches Communism in lectures, but still does in Tribune, the paper of the CPN. At the same time three novels appear which are a mixture of social reportage and fiction. South Seas (1934) is the best known of these. Still highly readable, thinks the biographer.

Painting of Jef Last by Piet Begeer, 1929

Painting of Jef Last by Piet Begeer, 1929© Museum of Literature, The Hague

Well-informed about what is happening in Germany, Last smuggles Jewish and other German refugees into France, where more and more writers are becoming Communists. But during the first congress of Soviet writers in Russia (1934), with delegates from forty countries including Last, new rules for socialist-realist art are laid down by Gorki. Experimental art is forbidden. Revolutionary artists and writers go on discussing this at a congress in Paris. Jef Last is one of the speakers. André Gide is also there and the admiration is mutual. The two writers – Last is 34 at the time, Gide 64 – become close friends. Both are struggling with communism and have problems with being at the same time homosexual and married. Under the influence of Gide Last gives his homosexuality a clearer place in his life and work. The older writer also convinces Jef that literature is more than ‘a weapon in the class struggle’, and that psychological nuances and doubt play a part.

Writers' delegation including Jef Last (left) and André Gide (centre, glasses) in the Soviet Union, 1936

Writers' delegation including Jef Last (left) and André Gide (centre, glasses) in the Soviet Union, 1936© Museum of Literature, The Hague

After a journey through the Soviet Union in 1936, Gide turns his back completely on Communism, while Last clings to the belief in a possible change in party doctrine applied to the Spanish Civil War. The decision to go and fight in Spain, despite the objections of the Dutch Communist Party (there are many anarchists among the Spanish Republicans), and despite his wife Ida and their three children. He writes to Gide that he “will not shirk the battlefield where all our ideals are at stake”. While travelling through Paris on his way to Spain, he was just able to read the first chapter of Gide’s Retour de l’URSS, the account of the French writer’s disillusionment. Last is alarmed. Although he shares Gide’s analysis, he fears that the book could have a negative impact on the struggle in Spain. He joins a fighting unit of workers in Madrid. But his friendship with Gide is known about and despite his military insight and courage he will find himself slandered and threatened by the Communists in Spain. Only in 1938, when he realises that Stalin sowed nothing but division and hatred among Spanish Republicans, does he decide to leave the CPN.

Only in 1938, when Last realises that Stalin sowed nothing but division and hatred among Spanish Republicans, does he decide to leave the Communist Party

Like all Dutch Spanish veterans Last enters the Second World War stateless and without rights, which for him is a period of constantly changing secret addresses, illegal (and a few legal) publications and resistance work. After the war he continues as an independent socialist. He no longer believes in the world revolution, but in future will fight colonial oppression and defend equal rights for homosexuals.

He was involved in protests against the war waged by the Netherlands from 1947 to 1949 in its former colony of Indonesia, although the latter had declared independence as early as 17 August 1945. From 1950 to 1953 Jef Last spends three years in Indonesia at the invitation of vice-president Mohammed Hatta. He works as a teacher and writes reportages. Back in Europe he receives a doctorate in Chinese philosophy in Hamburg, translates Chinese books and writes children’s books. In the 1960s he writes widely-read reports on the Far East. In 1966 his book My Friend André Gide appears and he finds an affinity with Provo, a playful anti-authoritarian young people’s movement (1965-1970). He dies in 1972.

Jef Last in 1968

Jef Last in 1968© Eric Koch & Anefo/Wikipedia

According to Rudi Wester the apparently so changeable and always rebellious Jef Last remained true to his own morality, which demanded that ideas, even changing ones, should be converted into action. In addition, she writes, Last was a brave man and a lively narrator, who was far ahead of his time. She was not able to convince me on the latter point, but fortunately her admiration has not prevented her from giving us in Is There a Stranger Life than Mine? a nuanced picture of Jef Last as a human being. It becomes clear that he was a very absent father, had no problem ‘organising’ boys for Gide, was considered domineering and irritating by many people and was not a really great writer. Certainly not a perfect hero then, but certainly a man with a strong will and remarkable resilience, who was certainly admired in the 1930s by the left in the Netherlands for his speeches, articles, political commitment and international contacts.

It is admirable that Wester has succeeded in plotting a path through the great number of jobs, conflicts, events, journeys, letters, publications and contacts of this Jack-of-all-trades. By retaining a chronological order, describing his publications as an extension of his political and moral choices and skilfully inserting fragments of interviews with Last’s children and friends, this massive biography finally becomes a supple and empathetic narrative on the tragic twentieth century. Highly recommended!

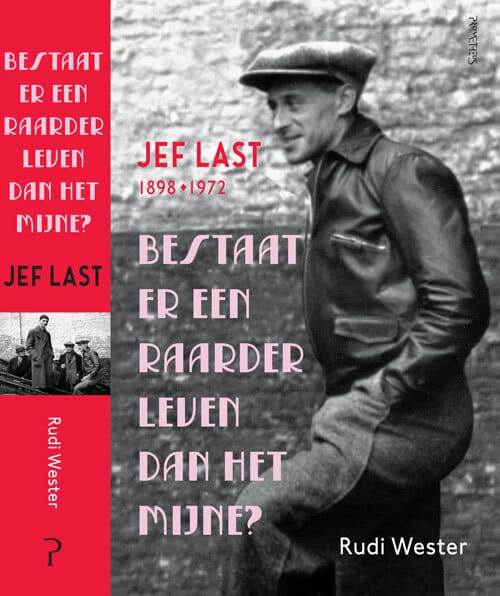

Rudi Wester, Bestaat er een raarder leven dan het mijne? Jef Last (1898-1972), Prometheus, Amsterdam, 2021, 500 pages.

English editions of books by Jef Last can be found HERE.