Hymn to the Silence: The Contemplative Work of Jef Verheyen

Forty years after his death, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp is devoting a retrospective to the Flemish artist Jef Verheyen (1932-1984). This beautiful exhibition is relevant not only as a part of art history but also because Verheyen continues to inspire young artists today.

Verheyen’s mission was contradictory: on the one hand, he wanted to continue the centuries-old Flemish painting tradition with paint and brush, and on the other hand, he desired a non-plastic painting, without recognizable representations and human traces, that reached for perfection and the infinite cosmos.

The fact that the unique artistic vision maintained by Verheyen is still alive among contemporary artists is evident. In its exhibition itinerary, the KMSKA presents subtle interventions by Ann Veronica Janssens, Kimsooja, Pieter Vermeersch, and Carla Arocha and Stéphane Schraenen. Like Verheyen, these artists also strive for an almost material-less, visual experience of light and color.

Jef Verheyen's 'Lux est Lex' with the Madonna by Jean Fouquet in between.

Jef Verheyen's 'Lux est Lex' with the Madonna by Jean Fouquet in between.© SABAM Belgium, 2024 / Fille Roelants

But the highlight of the exhibition’s intervention can be seen in the room of the fifteenth-century masters. The Madonna by Jean Fouquet, perhaps the most enigmatic work in this collection, is majestically flanked by Verheyen’s diptych Lux est Lex

(1974). Allegedly, it was Verheyen’s dream to see these canvases painted with matte lacquer hanging on either side of the fifteenth-century panel, a dream that is now fulfilled posthumously.

Ceramics

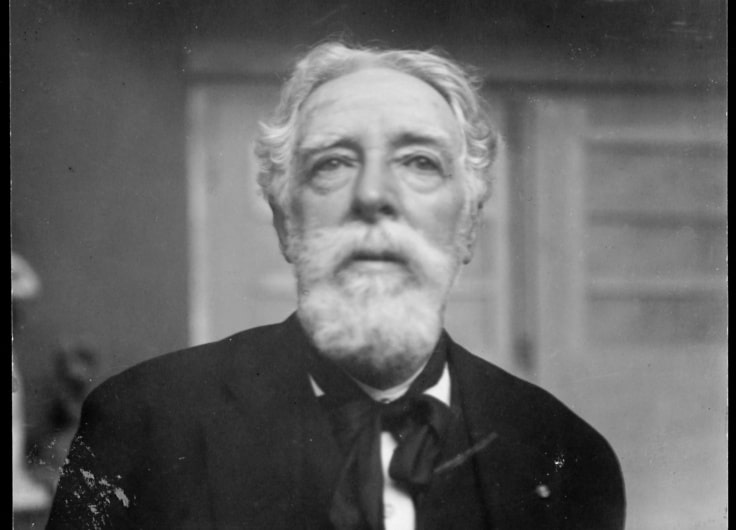

Jef Verheyen was a son of the De Kempen region, the eldest in a family of twelve. His father was a house painter, and his mother ran the paint shop. An eye disease saddled the young Jef with glasses with strong lenses for the rest of his life.

After the Second World War, Verheyen studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Together with several art students, he advocated the creation of a ceramics class, which was established in 1952, with Olivier Strebelle as its teacher. Of the many disciplines with which he became acquainted, ceramics appealed to him the most.

Jef Verheyen, Collection FOMU Antwerpen

Jef Verheyen, Collection FOMU Antwerpen© SABAM Belgium 2024 / Filip Tas

In 1953, after spending several months in Vallauris, in the south of France, where he saw Picasso at work, he and his partner Dani Franque opened Atelier 14: a ceramics studio and shop opposite the Rubens House in Antwerp.

He also immersed himself in Chinese monochrome ceramics and the Taoist and Zen Buddhist traditions. Encouraged by writer friend Ivo Michiels, author of The Book of Alfa, he once again turned to painting. In 1957 he discovered Das Bildnerische Denken, the book in which Paul Klee explains his theory. Verheyen was shocked to discover that for the past few years he had been working in the spirit of Klee, without realizing it.

'Real Milanese'

The meeting with the Argentinian-Italian artist Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), with whom he struck up a lasting friendship in Milan in 1958, provided a new stimulus for his development. Fontana, known for his carved canvases, taught him that the idea itself takes precedence over its execution.

During this period, Verheyen called himself Le Peintre Flamant (sic). Among other things, he felt an affinity with Jan Van Eyck and his glaze technique, but under the influence of Fontana’s spatialism, the Antwerp painter simultaneously pounded on the gate to infinity. In that period, Ivo Michiels noted that Verheyen’s oeuvre gradually turned into a ‘Hymn to the Silence’.

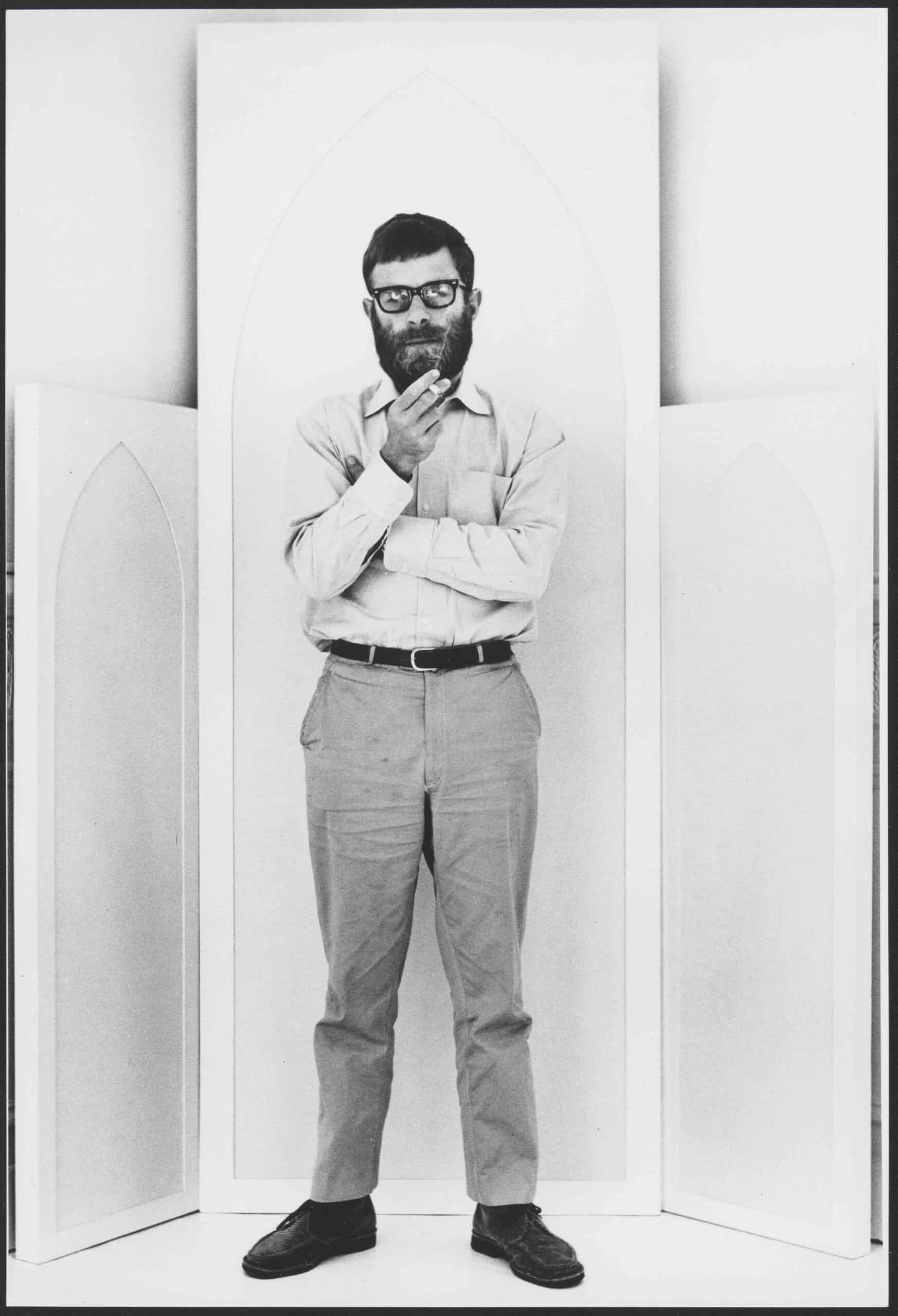

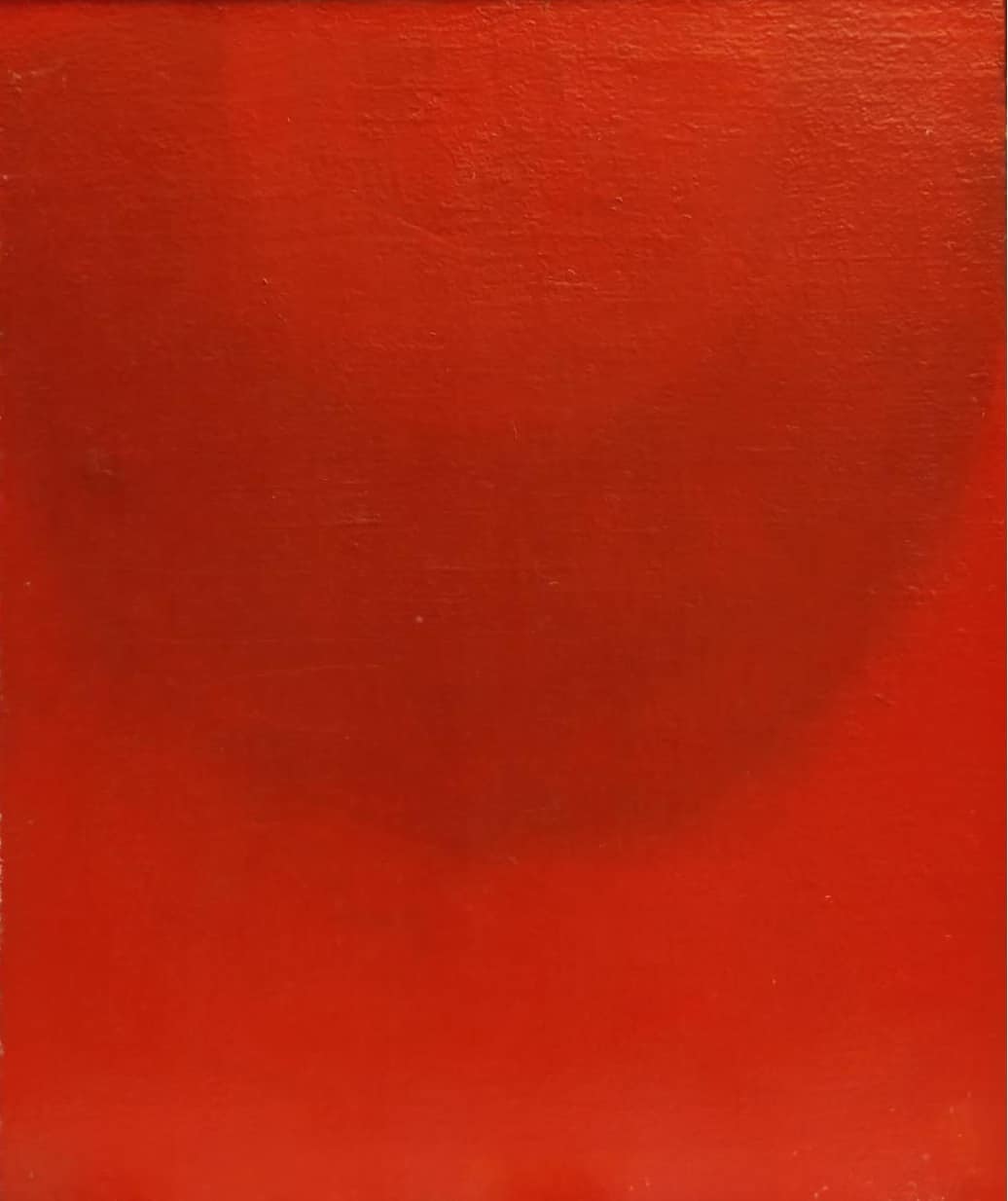

The artists’ group G58, of which Verheyen was one of the initiators, organised an opening exhibition in the Hessenhuis in Antwerp, where Verheyen’s red-coloured canvas L’air est plein de ta chaleur was on display. Fontana bought the work, which is now on loan at the KMSKA.

L’air est plein de ta chaleur (The air is full of your warmth), 1958

L’air est plein de ta chaleur (The air is full of your warmth), 1958© SABAM Belgium 2024 / Collection Fondazione Lucio Fontana

Michiels wrote about this period that Verheyen had become a real Milanese. Verheyen was busy philosophizing and discussing with colleagues and making plans for international projects. For example, he wanted to set up an international exhibition on monochrome painting and wrote a pamphlet for ‘Le Mouvement Stable’. But Yves Klein, who had also been asked to participate, thought that Verheyen had stolen ideas from him. Finally, a group exhibition of Group 58 took place in the Hessenhuis, which emphasized mobile rather than monochrome art. Jef Verheyen did not take part.

In the meantime, his pamphlet Essentialisme, for which he borrowed the term achromic painting from Manzoni, appeared in the French-language magazine Art Actuelen, and was published in the Dutch-language magazine Het Kahier. The pamphlet was also distributed in Milan. A quote from it: ‘The black space, the essential concept of black, each of us is a bearer of that concept, but to find it one must be able to break free from matter, the traditional rubbish, tachism and all other toil.’ A little further on in the pamphlet, he also took a swipe at Jorn and the art related to Cobra.

Rothko

Verheyen was also familiar with the American artist Mark Rothko, who made light vibrate in contemplative areas of colour. From the notes he made while working on the key work Le voile du mystère, it appears that the path Verheyen was taking was different: ‘I’ve been working on the same theme for two months now and it keeps on going. I no longer feel a form, only vibrating spaces, my canvas is the space itself and I don’t feel at all bound to the surface on which I work.’

‘Brugge’, ‘Metaponte’ and ‘Soleil II’

‘Brugge’, ‘Metaponte’ and ‘Soleil II’© Fille Roelants

In Rothko’s work, which contrasted areas of colour, earthly drudgery was visibly present: the brushwork expressed emotion, a hint of melancholy or pain. With his expanding, vibrating surfaces, Verheyen wanted to detach himself from these terrestrial matters.

When Verheyen’s work, together with that of Rothko and others, was displayed at the exhibition Monochrome Malerei in the Museum Morsbroich in Leverkusen, Verheyen’s canvases were in somewhat dark shades. Soon after, he let the white dominate with the suggestion of refracting light in rainbows and solar arcs. Verheyen realized that white was more suitable for detaching from matter. From then on, he spoke of panchromy, the feeling that all colours are present on the surface, even if they are not all painted.

Quatre mains and ZERO

Back in Antwerp, Jef Verheyen founded the New Flemish School in 1960, partly out of dissatisfaction with the situation at G58, with Englebert Van Anderlecht, Paul De Vree, Wim (Wannes) Van De Velde and others. The tone of the accompanying pamphlet was Flemish Nationalist and received a critical reception. The movement was short-lived, but most of its members kept in touch with each other.

For example, Van Anderlecht and Verheyen made a series of ten joint paintings. Verheyen painted the background and then it was Van Anderlecht’s turn. Verheyen set up similar collaborations with Paul De Vree, Lucio Fontana, Hermann Goepfert, and Gunther Uecker.

Verheyen was one of the few ZERO artists who stuck to pure painting, but like his associates, he avoided lyrical expression

During this period, Verheyen and his artistic friends found a permanent home in John and Jacqueline Trouillard’s Ad Libitum gallery in Antwerp. In the years that followed, Verheyen became the hub of the international network of ZERO artists, with whom he exhibited not only in Antwerp but in many foreign places as well. The ZERO movement harked back to the principles of abstraction as formulated by the constructivists. Artists such as Mack, Piene and Uecker made light installations, smoke paintings and nail objects, among other things. Verheyen was one of the few ZERO artists who stuck to pure painting, but like his associates, he avoided lyrical expression.

In 1964, Verheyen, assisted by Paul De Vree, Jos Pustjens, Jan Bruyndonckx and Julien Schoenaerts (voice), made the art film Essential, which is currently being screened at the KMSKA.

Le Matin des Magiciens (The Morning of the Magicians), 1979

Le Matin des Magiciens (The Morning of the Magicians), 1979© SABAM Belgium 2024 / Jan Liégeois

Judoka

Verheyen travelled a great deal, always looking for a different light. In 1974, he moved to Apt in Provence with his family. During this period, he developed a close friendship with gallery owner Axel Vervoordt, who was an important lender for the current exhibition.

Although Verheyen felt at home in the rolling landscape of the Luberon, where he frequently took horseback rides, Verheyen could often be found in Belgium. In 1979, he was given a retrospective at the PSK in Brussels and, together with museum employee Jean Buyck, organised a major exhibition on the ZERO movement at the KMSKA. The museum then purchased a fine ensemble of works by ZERO artists that included Fontana, Uecker and Goepfert.

Diamond I Floating Space, 1984, collection Jef Verheyen Archief

Diamond I Floating Space, 1984, collection Jef Verheyen Archief© SABAM Belgium 2024 / Axel Vervoordt Gallery

Five years after this exhibition, the artist succumbed to a heart attack. Verheyen, who was an avid judoka, was on the tatami mat at his local club in Apt at the fatal moment.

The man who bridged the gap between the Flemish painting tradition and conceptual-abstract art is not particularly well known in Belgium and the Netherlands, but his legacy lives on among the new generations of artists. And this is precisely what the KSMKA exhibition Window on Infinity attempts to show.

Jef Verheyen. Window on Infinity until 18 August at KMSKA

The catalogue of the same name has been published by Hannibal Books.