‘Jew’, a Loaded Word

In his latest book, historian and language journalist Ewoud Sanders provides an overview of all Dutch expressions and compound words in which the word ‘Jew’ appears. He seeks to reveal how deeply rooted many expressions of antisemitism are in our language.

After the opening of the new liberal synagogue in Amsterdam in 2011, tensions began to rise between synagogue visitors and a nearby vocational school (with many students from migrant backgrounds). In response, the Liberal Jewish Community (LJG) decided to invite the students to the synagogue and connect them with Jewish youth, hoping to foster greater understanding between them. This led to the project Leer je Buren Kennen (Get to Know Your Neighbors). During the visit, students are asked to anonymously write down their associations with the word ‘Jew’. And they do: terms like “rich, greedy, kosher, big nose, Torah, gas chambers, Hitler, sell their mother, own the media” emerged.

Ewoud Sanders

Ewoud SandersEwoud Sanders describes how prevalent antisemitic words and expressions were, how common, how they were taught from an early age, and how they sometimes still persist.

This is how historian and language journalist Ewoud Sanders (b. 1958) starts his book ‘Jood’, de vergeten geschiedenis van een beladen woord (‘Jew’, the forgotten history of a loaded word). The project continues, although the conversations have become difficult since the Hamas attacks of 7 October 2023, and the following war in Gaza. The war has led to an increase in antisemitic incidents and statements in the Netherlands and beyond. But even before the war in Gaza, the words and ideas that the young people wrote down at the LJG reflected a mindset that has existed for centuries. Sanders knows what he is talking about: he earned his doctorate degree with research on youth narratives about Jewish conversion (2017), and has authored several books where the depiction of Jews in Dutch-speaking culture plays an important role.

In 2024, Sanders believed it was the right time to revive an old plan: to explore how the word ‘Jew’ has been used throughout time in Dutch-speaking regions. He had already carried out a survey in 2005 for this purpose. Two thousand people from all age groups in the Netherlands and Flanders responded to the question about which expressions and compound words with the word ‘Jew’ they knew. To further inform his work, Sanders reviewed the annual reports from the Center for Information and Documentation on Israel (CIDI), which covered topics such as antisemitic language. And of course, he had the findings from Get to Know Your Neighbors. He also relied on a wide range of written sources from the Middle Ages to the present: religious texts, novels, children’s books, song lyrics, newspapers, and dictionaries.

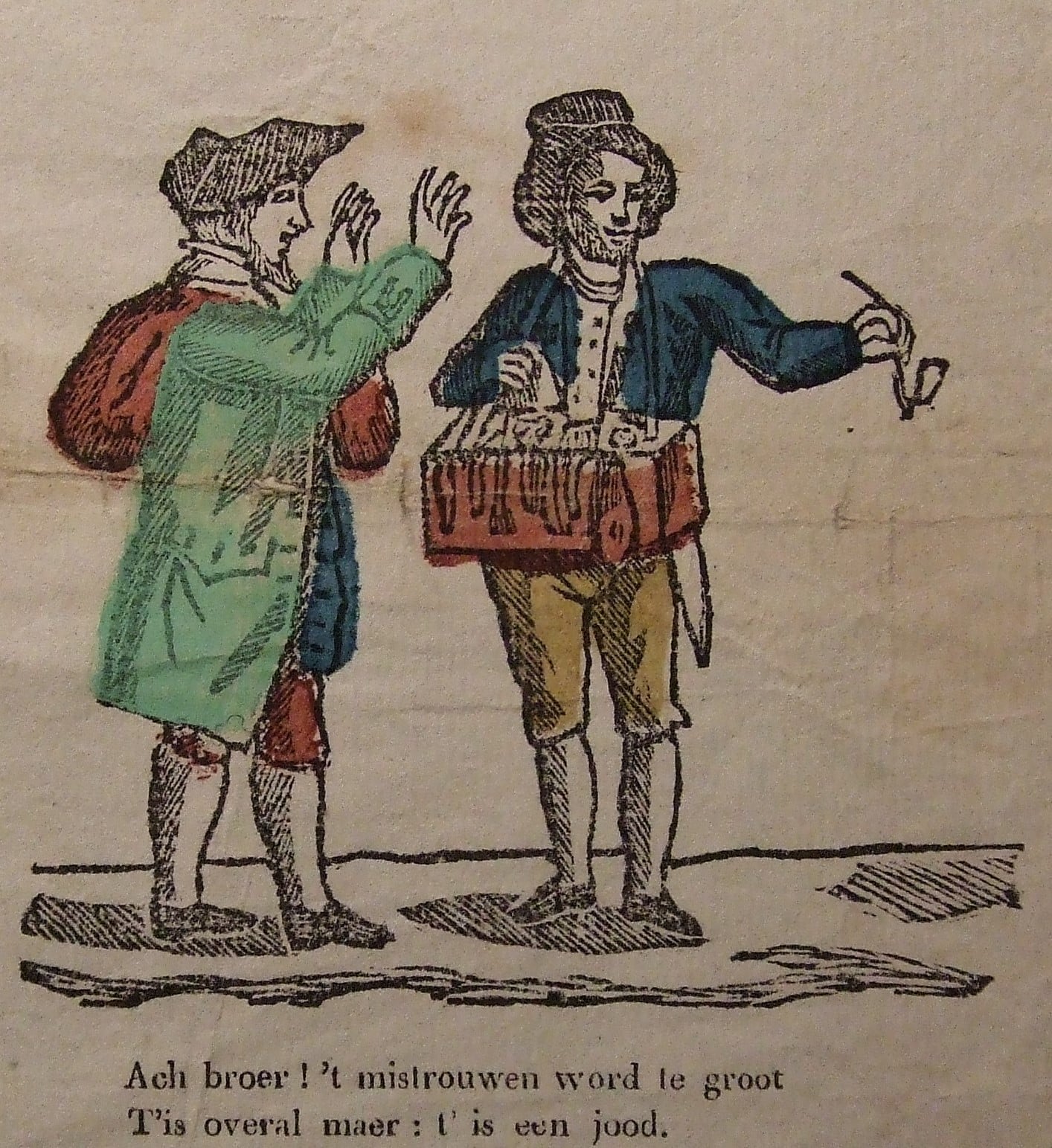

Two Jewish street traders in conversation. 'Oh brother, the mistrust is growing too much. Everywhere, it's just: it's a Jew.' Excerpt from a children's print from the first half of the nineteenth century

Two Jewish street traders in conversation. 'Oh brother, the mistrust is growing too much. Everywhere, it's just: it's a Jew.' Excerpt from a children's print from the first half of the nineteenth century© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Sanders provides a more or less thematic overview of Dutch expressions and compound words that include the word ‘Jew’, almost always with a negative connotation. Sanders explains that the book’s goal is not to discredit the myths that often underlie them. “That’s like fighting a losing battle. They’ve become part of our collective memory and seem impossible to erase. Still, I want to show how deeply ingrained many expressions of antisemitism are in our language. How prevalent they were, how common, how they were taught from an early age, and how they sometimes still persist.”

Sanders combines his findings with a brief history of Jews in the Dutch-speaking regions and lets the respondents of the survey describe the context in which they heard the words and expressions, and what they think about them. A historical fact often leads to an anecdote from a respondent, slightly disrupting the thematic flow. However, this is not really a problem. Sanders writes in a clear and engaging way, offering detailed explanations for readers who are less familiar with the subject without being condescending or judgmental.

The word ‘Jew’ first appeared in a twelfth-century rhymed Bible, at a time when, as far as we know, there were no Jews living in the Low Countries. By the thirteenth century, Jews were living in the region, although little is known about them. The writing of respected authors like Jacob van Maerlant and Jan van Boendaele about Jews during that period speaks for itself: they describe them as deceitful, hypocritical, and inherently evil. It is highly likely that these writers never met a real Jew. They wrote about the role of the Jews in the crucifixion of Jesus. Sanders clarifies that Jesus was crucified by Roman soldiers, but this was largely ignored in the Middle Ages. The Jews were commonly viewed as the murderers of the Savior.

And that brings us directly to an important source of hatred towards Jews: The New Testament. If people encountered a Jew during that time, the Bible was the only point of reference, which made the Jews an easy scapegoat, particularly when Europe was struck by the plague in the fourteenth century. Jews were accused of poisoning wells and were killed in large numbers, including in the Netherlands.

Postcard from 1908 with a colorized photo of Jodenbreestraat in Amsterdam, home to a lot of Jewish families.

Postcard from 1908 with a colorized photo of Jodenbreestraat in Amsterdam, home to a lot of Jewish families.© Joods Museum, Amsterdam

With the steady influx of Jews from the seventeenth century, Jews and non-Jews began to really get to know each other. In the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands, there were no ghettos, and different communities lived side by side. Jews did have fewer rights and were clearly identifiable as a minority group. From then on, judgments and prejudices about Jews emerged, no longer rooted in the New Testament, but based on their believed characteristics and peculiarities, as well as their religious practices. The expression “Het lijkt hier wel een jodenkerk!” (“It looks like a synagogue here!”) became a way to describe to a loud environment and, as the survey shows, is still in use. Some people considered it completely harmless.

People were often unaware that Jews themselves perceived certain expressions as offensive

People were often unaware that Jews themselves perceived certain expressions as offensive. A particularly painful example Sanders received came from a respondent who, serving as a translator in the British army, witnessed the liberation of Bergen-Belsen and was assigned to oversee a group of Dutch-Jewish girls. He managed to get them chocolate and cigarettes very fast. One of the girls asked, (Hoe komt u hier zo snel aan? (“How did you get these so quickly?”). “Hmm,” the man says, “Hoe komt een jood aan luizen?” (“How does a Jew get lice?”). That was a common answer to the question, “Hoe kom je daaraan?” (“How did you get that?”) at the time. He doesn’t mention how the girls reacted, but he does point out that it was the last time he used that expression.

Religious practices and the stereotypical Jewish features were mocked

In addition to these supposedly innocent expressions, Sanders also came across expressions that were clearly intended to be hurtful. In 1796, Jews were granted full civil rights in the Batavian Republic. This often provided a reason to emphasize their differences. Religious practices such as circumcision and the practice of not eating pork were ridiculed, and the stereotypical Jewish features – a crooked nose, a long beard – were also mocked. As emancipation progressed, it led to terms such as ‘jodendokter’ (‘Jewish doctor’), ‘beursjood’ (‘stock-market Jew’), and ‘diamantjood’ (‘diamond Jew’).

After the war, many of the antisemitic expressions mentioned are now seldom heard, but that doesn’t mean the views disappeared

In the meantime, non-Jews questioned whether Jews really belonged. Abraham Kuyper, the Protestant politician and pastor who founded the Anti-Revolutionary Party (ARP) and served as prime minister from 1901 to 1905, wrote several pamphlets towards the end of the 19th century that we would certainly label as antisemitic today. His attacks were directed at the non-religious Jews – the so-called ‘spekjoden’ (‘bacon Jews’, secular Jews). Jews controlled all the important institutions and were in charge in Europe. Despite their exceptional traits, they could never become true Dutch citizens because they were fundamentally different in looks and behavior. They were allowed to retain their civil rights, but they were reminded not to forget that they were merely guests. This text was published in full in the first party program of the ARP, and large parts of it were later incorporated into a 1934 brochure by the National Socialist Movement (NSB).

Kuyper was a highly influential and respected figure. The fact that his views didn’t provoke mass protests speaks volumes about the attitude towards Jews up until the Second World War. After the war, such texts were no longer written, just as many of the expressions mentioned in the book are now seldom heard, but that doesn’t mean the views disappeared. The internet is full of them, says Sanders.

The final chapter focuses on the history of the word ‘Jew’ in the Dikke Van Dale, the most prominent dictionary of the Dutch language. Older readers will likely recall the debates that began in the 1970s about the definitions of words that included ‘Jew’. There was often no mention that it was an insulting term. Some people argued that such a word shouldn’t be included in the dictionary. Editors defended themselves by pointing out that Van Dale is a descriptive dictionary, but the most recent edition shows that not only the mention of “offensive” or “hurtful” has been added, but several compound words with ‘Jew’ have also been removed (the same has been done with the term ‘negro’). Sanders calls it self-censorship. He rightly argues that: “Antisemitism doesn’t disappear by removing words. However, it does remove an important means of addressing it, such as in court”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.