Johanna McCalmont’s Choice: David van Reybrouck and Rachida Lamrabet

Every month, a translator of Dutch into English gives literary tips by answering two questions: which translated book by a Flemish or Dutch author should everyone read? And, which book absolutely deserves an English translation? To get publishers excited, an excerpt has already been translated. Brussels-based Irish translator Johanna McCalmont wants to draw your attention to two high-profile books that use Africa as a backdrop for a gruesome past.

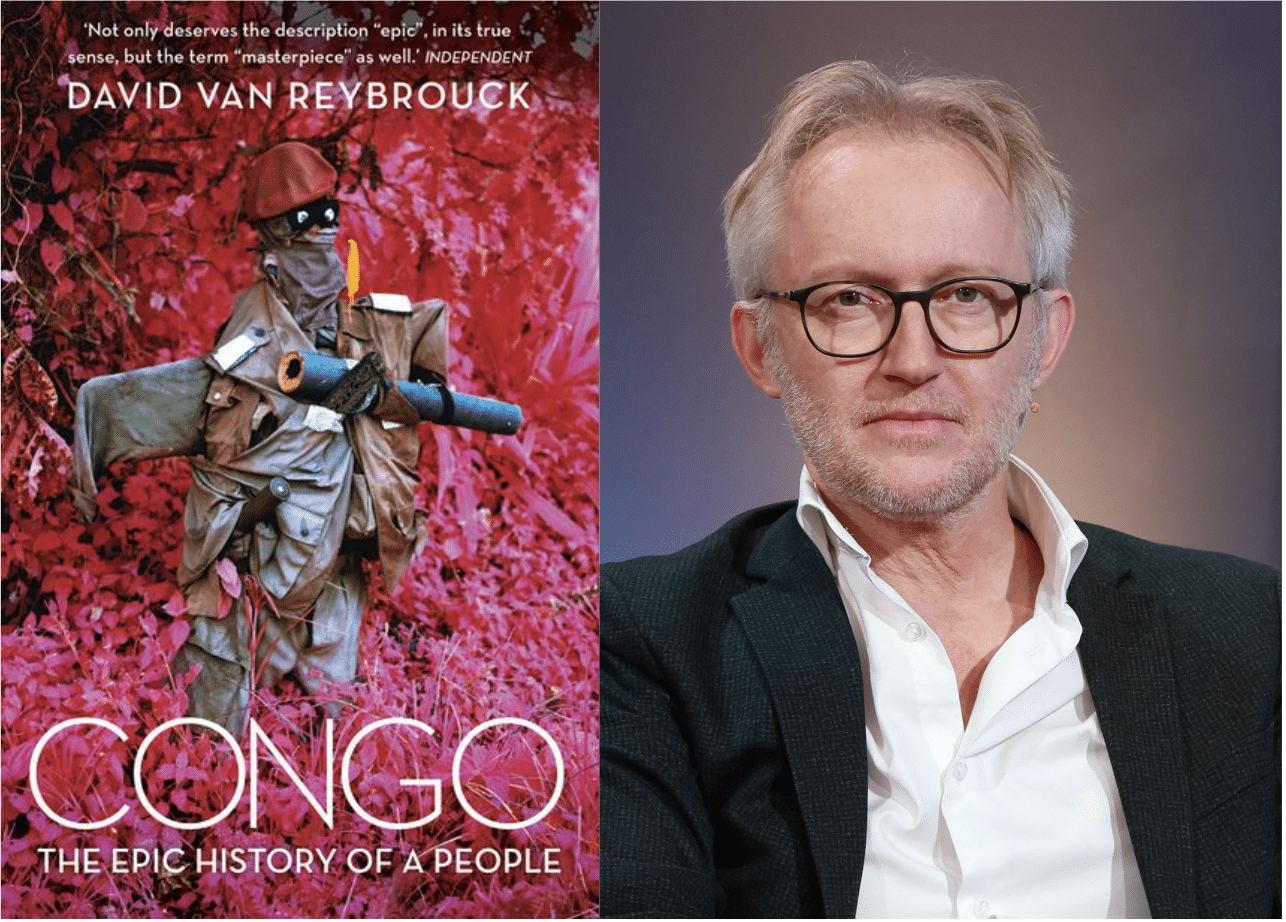

Must-read: ‘Congo, The Epic History of a People’ by David van Reybrouck

© Elena Ternovaja / Wikipedia

At just over 550 pages, there is no denying that this history of Congo from 1870 onwards is a hefty tome. Van Reybrouck, however, invites us to sit with the many Congolese to whom he spoke while researching this book “in a bid to at least challenge the Eurocentrism [he] would undoubtedly find on [his] path.” His conversations with a host of characters, such as former child soldiers, government officials, or miners, transform this detailed history into a page-turner with a very human side. Their testimonies breathe life into the individual experience of History as they recount gut-wrenching memories of violence during Belgian colonization, epidemics decimating entire communities, inhumane conditions for railroad workers and miners, and endless feuds, both political and armed. Others relish in a sense of impunity, despite the crimes or corruption in which they were involved. There are upbeat tales, too, such as the trendsetting young ‘Sapeurs’ who protested Mobutism with their flamboyant style; Van Reybrouck’s accidental appearance onstage beside superstar Werrason; or the Congolese now doing business in China.

At a time when conflict rages once again in eastern Congo, the chapters on the country’s more recent history are perhaps of greatest interest today: the exploitation of coveted ores; the spill over of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda and political tensions in Uganda; and the role and (in)action of UN and EU peacekeepers. As Van Reybrouck—in Sam Garrett’s vibrant translation—recounts, Congo’s history is not just about colonisation, or decades of Mobutu rule, or even life under the Kabila dynasty, but one that has also been shaped by other foreign powers, such as France, the USA, the UK, Russia, Western multinationals, and increasingly China.

While relations between Belgium and Congo have significantly evolved since Congo was first published in Dutch in 2010, and Van Reybrouck has acknowledged he would approach his analysis differently were he to write the book today, this detailed history still has much to offer—and is much less daunting a read than it appears.

David Van Reybrouck, Congo, The Epic History of a People, translated by Sam Garrett, Fourth Estate, 2014, 639 pages

David Van Reybrouck, Congo, The Epic History of a People, translated by Sam Garrett, HarperCollins, 2015, 656 pages

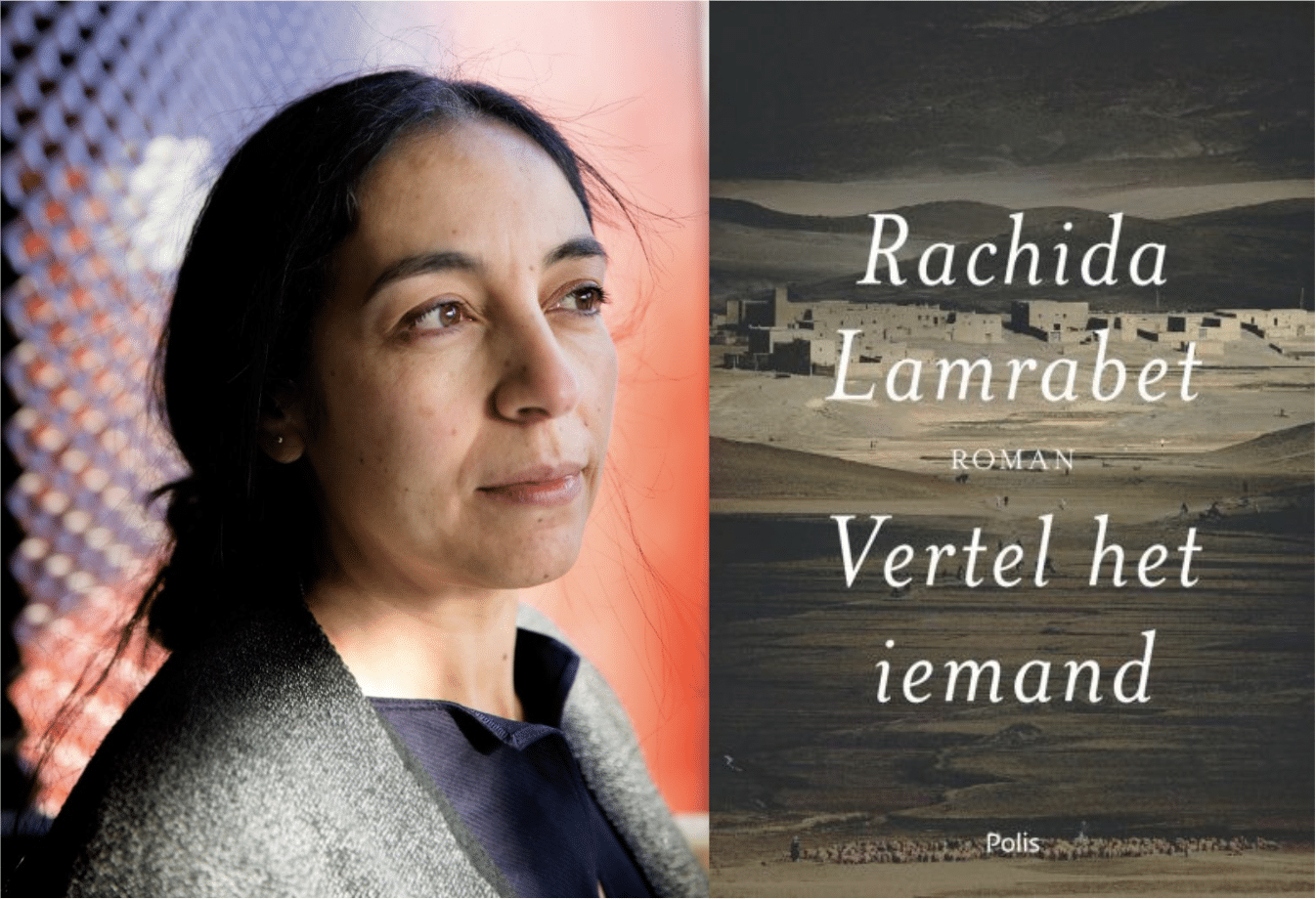

To be translated: ‘Vertel het iemand’ by Rachida Lamrabet

© Koen Broos

I was first drawn to Rachida Lamrabet’s work after hearing her speak at the Asmara Addis Literary Festival (in Exile) in Brussels where she talked about showing a different side to her male characters, one that went against the grain of expected stereotypes of (young) Flemish-Moroccan men in particular. Her award-winning short stories and novels are full of male protagonists who are complicated, ‘weak’ characters, and Vertel het iemand

(Tell Someone) is no different.

Set during WWI, Vertel het iemand is essentially a story about war: conscription; the horrors of the trenches; a young soldier court-martialled. Yet, that is only half of it. The story opens in Fez, Morocco, occupied only a few years earlier by the French. The narrator, a French artist who has travelled the region for years, recounts the moment he realises that the mysterious young Amazigh man who has been following him is in fact his son. After being thrown in prison for fighting in the street, the young man accepts a deal: spend a year fighting in France in exchange for his freedom.

But the young, unnamed soldier is accused of a plot against the French, and is court martialled. As he recounts his life story to his father in his cell the night before he faces the firing squad, we are transported to the desert village where he grew up, the sheikh’s school where he learned Arabic and studied the Koran in his search for God, his training at the barracks in Fez, and finally life on the frontline in France.

Lamrabet’s language is both sparse and poetic—capturing the oppression and violence inflicted through colonization and a war in which many struggled to understand their identity and role—while the relationship between the two men ultimately serves as a parallel for the history between France and Morocco.

Rachida Lamrabet, Vertel het iemand, Polis, 2018, 256 pages

Excerpt from ‘Vertel het iemand’, translated by Johanna McCalmont

‘Yemma,’ he said before collapsing on the chair.

I knew very well he wasn’t any old passer-by, just another one wanting to admire my talent.

I have never been religious. Nor have I ever really known fear, even though I have been in the most perilous of situations. However, when I saw him holding my drawing of his mother, I was sure he had come to settle a debt I never thought I would have to repay. God never forgets. I had separated myself from my kind and my culture.

Could he have been my son if I had raised him in my faith and my language?

Could I have saved him?

What if I had been able to save him? I’d have saved him before he was born. I’d have saved her, the sun girl. I’d have been a man who saved his wife and child. I’d have been a husband and father who shouldered his responsibility. But I had not, because how can you be a father to a child who is not one of your own? It felt like an evil charm had been cast on the pair of us in that room. He stared at the drawing as I tried to suppress the doubts welling up within me.

I cursed the day he had first looked over my shoulder at my drawings. What did he want from me? For a long time, I had told myself I didn’t need to look back. Only the future mattered, the past was gone and meaningless. Just as the truth had vanished and was of no significance to anyone.

‘Why did you draw my mother?’ he asked.

I tried to hide my confusion and told him I had lived in her village for a while, that I had drawn everything I could, including the girls and boys.

He wanted to know the name of the village and where it was. He asked if I had witnessed the attack by the sultan’s askars. His mother had apparently fled the village with him during the attack. He had only been a few weeks old, and they had never returned to their village.

There hadn’t been any animosities when I lived there. I remembered the village as a place where time seemed to stand still. Nonetheless, I had sensed that some young men were suspicious. They didn’t trust me and my sheets of paper. The amghar, the village chief, made it extremely clear to them at the time that I was welcome and could come and go as I pleased. Most of the young men’s suspicions gradually waned and some were even friendly towards me.

I hadn’t come to the village to forge friendships or understand how those people lived and thought. There wasn’t really much to understand; they believed in fate. Things either happened, or didn’t happen, and all they could do was say Inshallah.

‘Did you know my father?’ he asked.