Joyce Overheul Alerts Us to the Resilience of the Underdog

Dutch artist Joyce Overheul is not afraid to unravel the loose threads that constitute the fabric of society. Using textile techniques and historic research her work grants the final word to those often overlooked.

Joyce Overheul

Joyce Overheul© Sabine Metz

Joyce Overheul (b. 1989) knows she has a sharp mind and is not afraid to speak it. She describes herself as someone who is unable to leave injustice unaddressed, whether it concerns the waiter who thinks women should not drink beer, or the older, male artist who says she concerns herself with mere “feminine” subjects.

But do not make the mistake of confusing an unambiguous opinion with a simplistic artistic practice. Take for instance the range of media she applies, exemplary of the complexity of her work: from web design to fabrics. And although she enjoys collaborating, she does not mind doing research by herself. Research that, as so much research these days, she jests, often starts on English Wikipedia.

Hijab protests

Overheul explains that the possibilities of unexplored media and materials excite her. However, at the end of the day, the narrative matters most and form follows it. The artist’s love for diversity is also present in her subject matter, although a specific theme has risen to the surface in the last few years: the position of the underdog, who is often female.

Overheul draws attention to emancipation, but also the responses emancipation elicits and the resistance it encounters. Thematically again a broad topic, as she approaches and converges different cultures and collaborations in history.

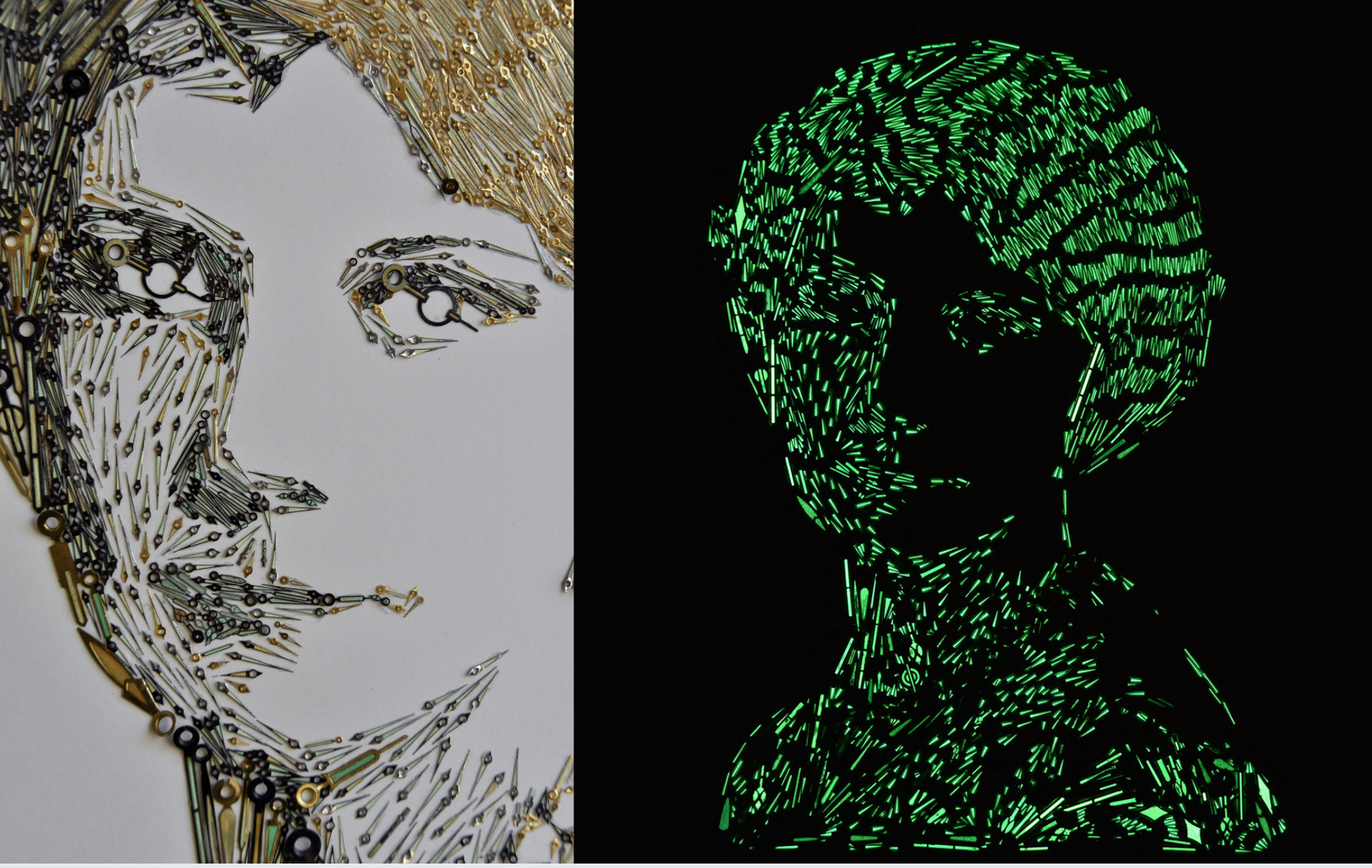

The Radium Portrait, Portrait of Grace Fryer (1899-1933), made of antique and vintage luminous watch hands on paper, 2020-ongoing

The Radium Portrait, Portrait of Grace Fryer (1899-1933), made of antique and vintage luminous watch hands on paper, 2020-ongoing© Joyce Overheul

Recently she made Radium Girls (2020), a portrait of American labourer Grace Fryer, made with – through radiation – luminescent hands taken from a watch. In 1920, Fryer was exposed to radioactive paint in the factory where she worked. Together with other ill, but combative radium girls she led the legal challenges to their formal employers that ended up being crucial to the labour rights movement. The underdog is resilient, and her story deserves to be told, not in the least because of that fact.

The underdog is resilient, and her story deserves to be told, not in the least because of that fact

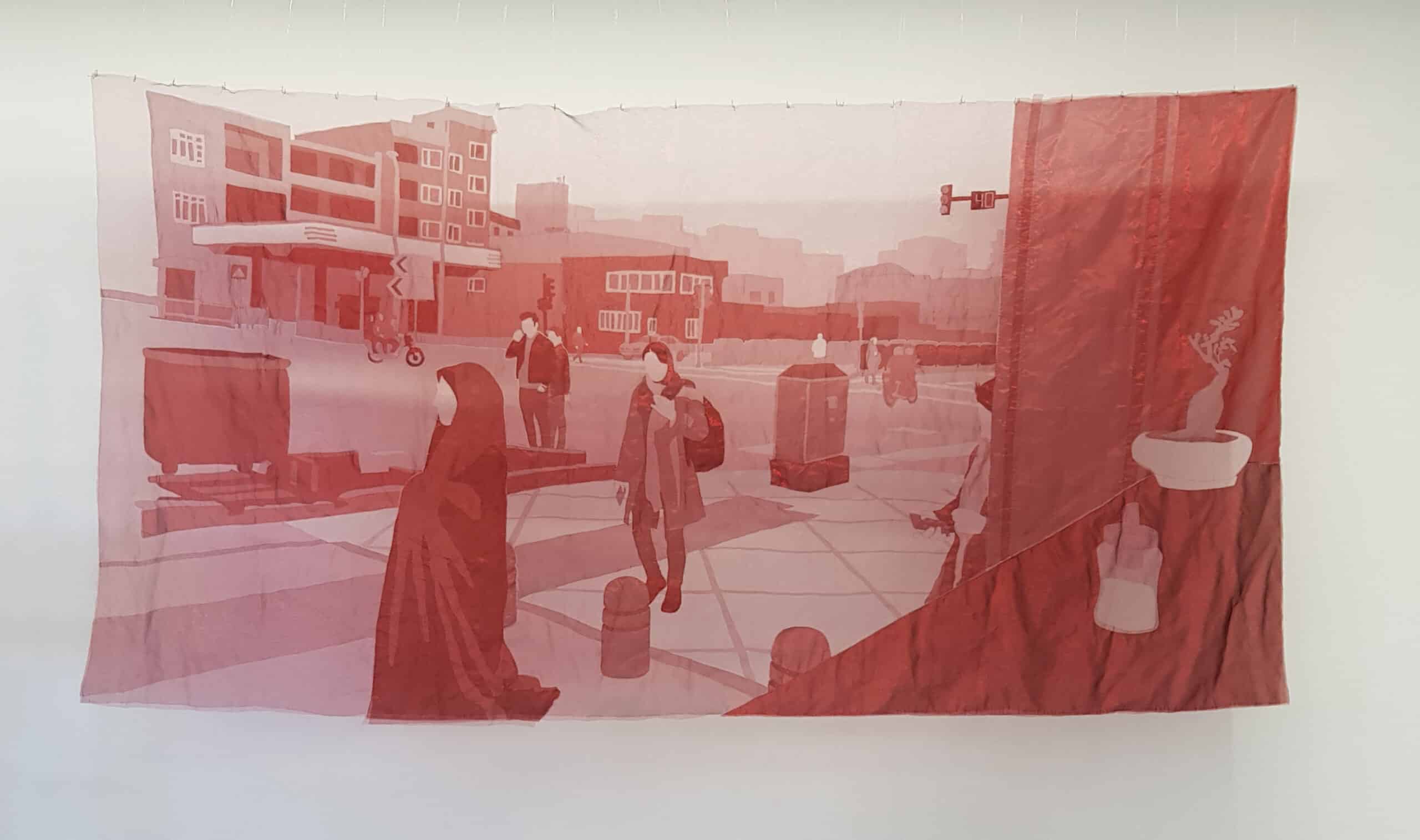

You could call Overheul’s work documentary, not because of how it deals with realism or objective registration, but because of how it approaches reality artistically. Intriguing examples are the large tapestry Utility Box on Enghelab Street (2019) and the related series Iranian Velvet, part 2 (2019). These textile works originate from a residency in Teheran (Iran), where Overheul learned, through a friend from college, about the controversial hijab: the Islamic law that requires women to cover their head and body, which has been legally challenged in Belgium. Critics point to the fact that this prescription makes no difference between those who chose it for religious convictions and those who are forced to obey it.

Utility Box on Enghelab Street, hand-sewn tapestry made out of red organza, nylon thread, embroidery floss and beads, 2019

Utility Box on Enghelab Street, hand-sewn tapestry made out of red organza, nylon thread, embroidery floss and beads, 2019© Joyce Overheul

In 2017 the Iranian Vida Movahed went viral by climbing up an electricity box, taking of her hijab, attaching it to a stick and holding it before her. Many fellow Iranian women followed suit and Movahed became known as “the girl from the Enghelab street”. Since then, the government has been placing a type of roof on the electricity boxes to ward off protesters, as visible in Utility Box on Enghelab Street.

Feminist “boerenbont”

Overheul’s photographic registration of the electricity boxes with their odd roofs posed an unexpected problem: she could not just publicize these images online. Any women associated with, or even found in the proximity of, these boxes could be labelled a protester by the Iranian government through facial recognition software. By turning the photographs into textile works Overheul managed to anonymize the women in the scenes, an effective, low-tech solution for a high-tech threat like facial recognition software.

For her tapestries, Overheul worked with fabrics she used to consider typically Iranian, until she later found them in a store in Den Bosch. It made her realize that even in Iran fabrics are imported from Turkey and China. These kinds of discoveries give her a sense of connectivity: cultures that seem – or are suggested – to be very different turn out to have a lot in common.

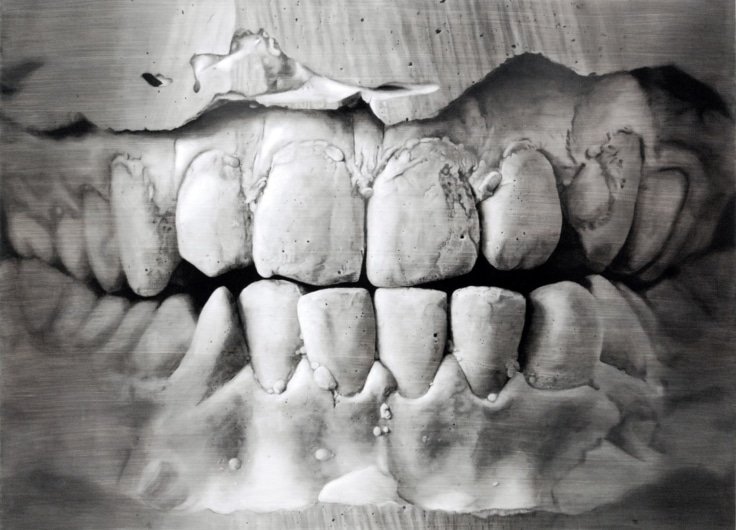

Iranian Velvet, part II, Private photos transformed into velvet tapestries, 2019

Iranian Velvet, part II, Private photos transformed into velvet tapestries, 2019© Joyce Overheul

Textile work has long been considered “feminine labour” instead of real art. Since the middle of the last century, there has been a renewed interest in it in art- and design circles, and even now contemporary artists (for example the Belgian Hana Miletić) often chose this medium, frequently because of its specific feminine history.

The embroidery technique Overheul is currently studying has a tradition that goes back millennia, something that excites her. To supplement her artist income, she owns a webshop selling crochet patterns.

Textile work has long been considered “feminine labour” instead of real art

This does not mean Overheul does not harbour any criticisms toward these “feminine” techniques and traditions. For example, she learned that the popular “boerenbont” – a colourful painting technique usually applied in tableware – was historically produced by women, as they were a cheaper labour force.

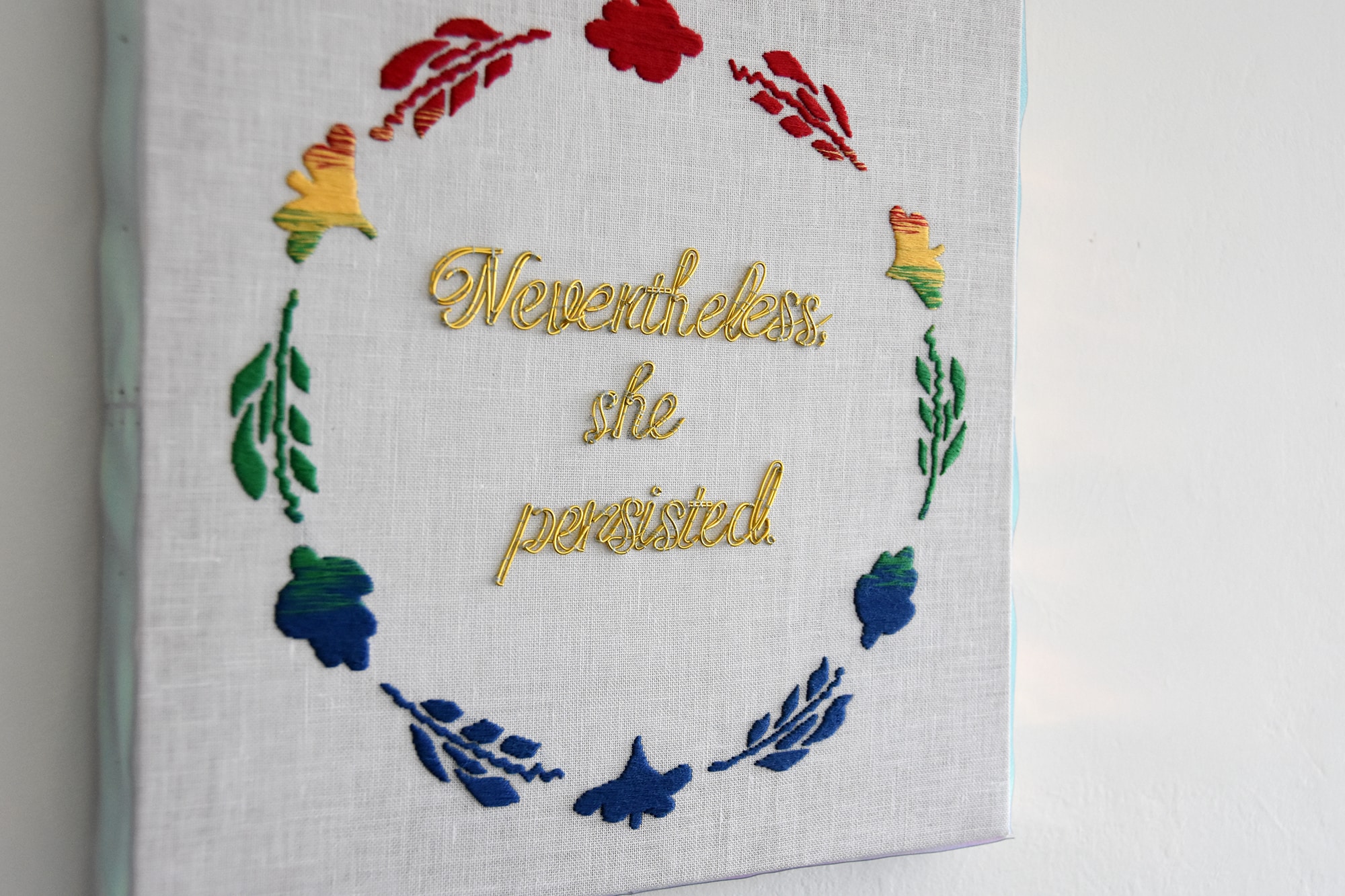

She combined this fact with a quote about American politician Elizabeth Warren, who – despite patriarchal resistance – did not let herself be silenced: “She was warned. She was given an explanation. Nevertheless, she persisted.” The slogan, particularly its last sentence, was proudly adopted by feminists. Overheul embroidered the words, surrounded by the typical “boerenbont” colours (For You, María Hernández, 2018).

For You, María Hernández, 2018

For You, María Hernández, 2018© Joyce Overheul

This conjecture of theme and medium sits uneasily, as is often the case in Overheul’s work. By pulling at the threads of our complex societal and historical fabric she unravels the assumption that you can pay women less than men or silence them without consequence.

Shallow pockets

Overheul encountered another one of those threads when she started a research project on sexism in fashion, specifically as it concerned pockets. It started with the observation that she did not have much space for things in the few and shallow pockets of her trousers. Other women shared similar experiences, sometimes adding that their male partner had ample storage.

Overheul started investigating and discovered a history that leads back all the way to the corset. Before the corset made an appearance, women were often given many pockets in – or underneath – their clothes. After the introduction of the corset this changed. Yet even as the corset went out of style, pockets did not make a return in female fashion. It was argued that pockets would make women seem larger and ungraceful. However, women’s own opinion was never consulted.

In the seventeenth century, a beaded purse was introduced which was supposed to be worn above your clothes. At first, this was considered vulgar – pockets were considered underwear – but eventually, it evolved to the modern handbag.

Chanel 2.55 in Retrospect: replica of a Chanel flap bag in the style of a historical bead pouch. 53583 glass and gilded beads, cotton yarn, iron wire, 2020. Thanks to Centraal Museum and Ninke Bloemberg.

Chanel 2.55 in Retrospect: replica of a Chanel flap bag in the style of a historical bead pouch. 53583 glass and gilded beads, cotton yarn, iron wire, 2020. Thanks to Centraal Museum and Ninke Bloemberg.© Joyce Overheul

This historic development is comically surmised by Overheul in a handwoven Chanel handbag in the style and material of a historic beaded pouch (Chanel in Retrospect, 2020). If you think about it, the development of the handbag exposes a ridiculous pattern, considering that women’s wages are already lower than their male counterparts, and they are expected to spend it on a bag because others – often men – assume women would not like deep pockets.

Eventually, Overheul’s artistic research will resolve in, amongst other things, a glossy magazine, for which she would like to collaborate with fashion editors. This way, she hopes to not only unravel the fabric of society, but also help rearrange it.