Jozef van der Voort’s Choice: Geert Mak and Maartje Wortel

Every month, a translator of Dutch into English gives literary tips by answering two questions: which translated book by a Flemish or Dutch author should everyone read? And, which book absolutely deserves an English translation? To get publishers excited, an excerpt has already been translated. This time you will read the choice of Jozef van der Voort, whose co-translation (with Babette Lichtenstein) of Nobody Lives Here, a Holocaust memoir by Lex Lesgever, has recently been published by The History Press.

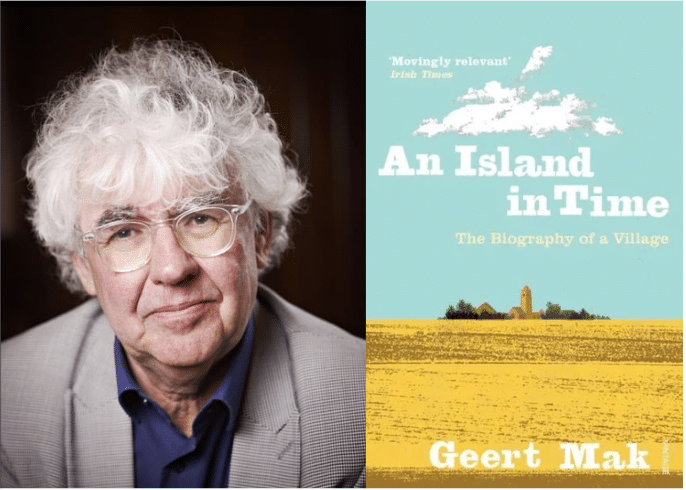

Must-Read: ‘An Island in Time’ by Geert Mak

Of the many books written by the prolific journalist and non-fiction writer Geert Mak, the one that has stayed with me the most is An Island in Time: a dive into the twentieth-century history of a Frisian farming village named Jorwerd, and an elegy for an ancient way of life that disappeared, almost unnoticed, over the course of just a few decades of industrialisation and intensification.

This is a story that played out over the whole of Western Europe, and Mak is well armed with facts and figures to illustrate the general impact of post-war mechanisation, urbanisation, and government policy on rural life. Of course, many of these changes were positive; the privation and drudgery of subsistence farming are not romanticised here. But by focusing on Jorwerd, Mak is able to explore what it meant on a personal level when jobs were lost, smallholders were forced to sell up, shops and pubs closed, young people moved away, and village life grew more atomised. This desire to understand macro-historical trends, both good and bad, through the lives of ordinary men and women is what makes An Island in Time so rich and resonant for me.

Geert Mak, An Island in Time: The Biography of a Village, translated by Ann Kelland and Sam Garrett, Penguin, 2010, 304 pages

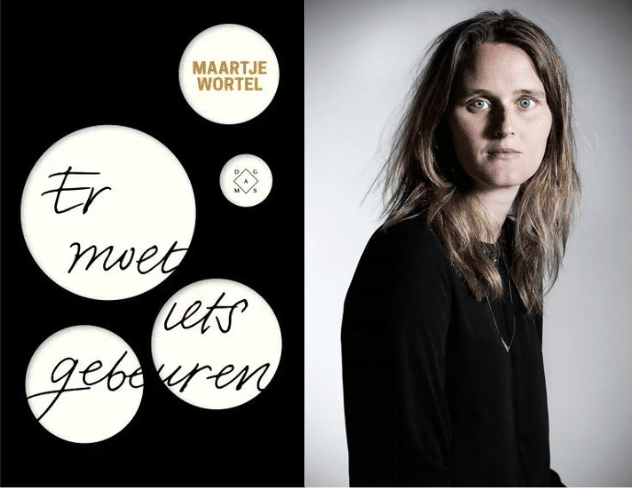

To be translated: ‘Er moet iets gebeuren’ by Maartje Wortel

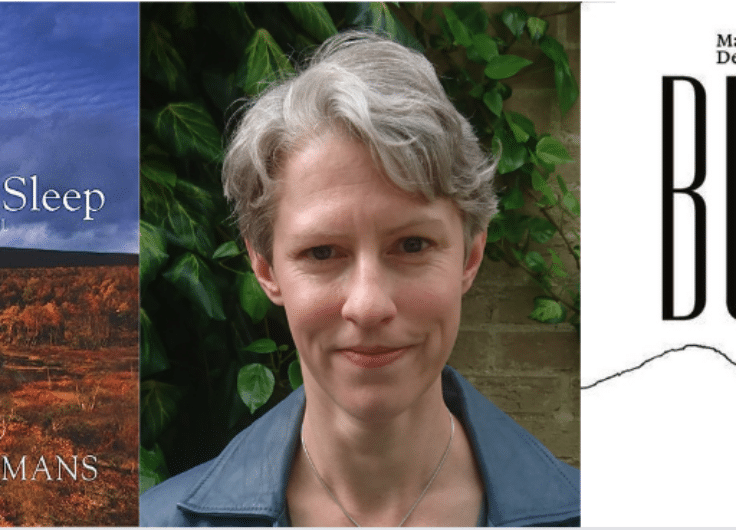

© Keke Keukelaar

I first encountered Maartje Wortel when I had the privilege of translating three stories from her collection Er moet iets gebeuren (Something has to Happen), and I enjoyed it so much that I translated another just for fun. (You can see the result below.) Wortel is, I think, one of the most interesting and distinctive writers working in Dutch. I could also recommend her novels, especially Dennie is een Star – an extended ode to the narrator’s cat – or De Groef, a book about walking laps of a park. But it’s her short stories that I keep coming back to.

As you might have gathered, Wortel’s plots can be idiosyncratic: in one tale, a couple grieving the death of their dog console themselves by getting on all fours and barking; in another, a depressed woman joins an all-male therapeutic camp where participants scream at trees. The tone is deadpan – half amusing, half unsettling. Yet despite her inscrutability, Wortel achieves considerable emotional depth. Other stories about the inner lives of grieving parents, a couple unable to conceive, and a narrator who travels to a North Sea island to get over a failed relationship are among the most evocative depictions of loneliness and longing I’ve ever read.

Maartje Wortel, Er moet iets gebeuren, Das Mag, 2015, 240 pages

Excerpt from ‘Er moet iets gebeuren’, translated by Jozef van der Voort

A Hunger to Soothe

Gradda knew very well that she didn’t exactly look like someone you’d want to touch, which was why she liked to touch other people. She tried not to be too blatant about it: she shook hands, just like everyone else; she gave the usual three kisses on the cheek; and on public transport she would brush her leg against other passengers’ legs—all for ever so slightly longer than was normal, but not long enough for anyone to get any odd ideas about her. Yet now, at the age of sixty-seven, she longed for more.

Gradda had no illusions that she would find someone, but she had enough money now Joop was dead. She could pay for it with her inheritance. She placed an advert. And then Sebastiaan came along. But before him, there’d been Joop.

She’d spent thirty-five years married to a sternly devout man named Joop, and strictly speaking, she was still married to him. When they’d first got to know each other, she’d been so incredulous that anyone would want to be with her that she’d said, I don’t mind what you do with other girls as long as I don’t find out about it. I don’t have to be the only one, as long as you make me feel like I am.

Joop had felt offended. He’d told her there was nobody else and there never would be. And even though it was probably the truth, in all those years Gradda never felt for a moment like she was the love of his life. Maybe that was God’s fault. She was often struck by a jealousy she couldn’t explain. It wasn’t her, but some invisible force that kept Joop in his place. She’d tried to understand her husband, she’d gone to church with him, she’d prayed with him before dinner and celebrated every Christian holiday, and yet God had never found her. She thought, If He’s so great—greater than mankind—then surely He can seek me out too? Surely it doesn’t have to be so hard?

Joop felt everyone bore their own individual responsibility towards the Almighty. He said, You need to conduct yourself according to His truth, the written word; you need to be ready to give your whole life over to the search for Him; but in the end, it’s He who decides whom He will touch.

Gradda had barely reacted to Joop’s words, but they’d left her blackened on the inside. That was how it felt—as if something in her had burned to ashes. What did it mean if not even He wanted to touch her? What was wrong with her?

Read the rest of the story HERE.