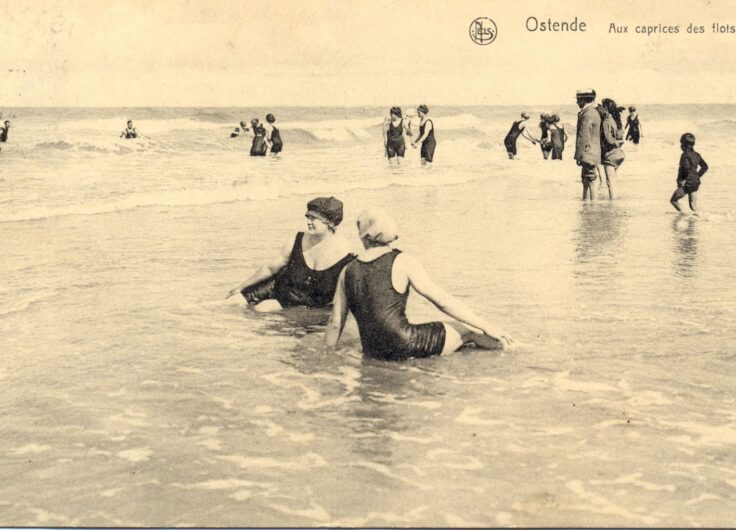

Eighteen young writers from Flanders and the Netherlands have brought nineteenth-century artefacts from the Rijksmuseum to life. They wrote their stories in response to the question: what do you see when you look at these objects through the lens of impending doom? Jutta Callebaut was inspired by Jan Veth’s Portrait of Cornelia, Clara and Johanna Veth. ‘He may have an eye for composition, but we developed a talent for washing, cooking, cleaning and resentment.’

Jan Veth, Portrait of Cornelia, Clara and Johanna Veth, 1885

Jan Veth, Portrait of Cornelia, Clara and Johanna Veth, 1885© Rijksmuseum Collection, Amsterdam

The Girls

My sisters and I have been granted the rare privilege of posing for the incredible genius that is Jan Veth. The blessed artist, the great promise of contemporary Dutch painting. Jan Veth, the young man who does not eat the crusts of his bread because they irritate the roof of his mouth. Jan Veth, our baby brother.

When we were little, Jan and I were inseparable. We would run across the fields, hide out by the riverbank, model figures with clay-like mud, scratch imaginary animals into the bark of trees and draw portraits on any old scrap of paper we could find. A good drawing requires a good eye, our father used to say. I was younger, but better at sketching than Jan.

‘Jan has to practise and needs models, girls; he can’t paint landscapes every single day,’ our mother said. ‘Yes, the girls will pose.’ It was a foregone conclusion. ‘The girls’ will sit still for two, three days for the sake of their brother’s self-development. ‘The girls’ have nothing better to do anyway. We had a long list of chores awaiting us, but the art of painting is obviously more urgent than dirty dishes.

He may have an eye for composition, but we developed a talent for washing, cooking, cleaning and resentment.

My parents always address my sisters and me as ‘the girls’. I have more in common with Jan than with Cornelia and Johanna. But because we are of the same sex, we are seen as one entity. You have to hand it to my parents: they were able to see with the naked eye that – yes indeed, long hair and breasts! – we are girls.

Jan undoubtedly gets his fine powers of observation from them.

For a while, to make a point, I addressed him exclusively as ‘the boy’. I’d ask if ‘the boy’ could pass the cheese or if ‘the boy’ was able to take his own knife out of the cutlery drawer or whether he required assistance? He cannot be held accountable for my parents’ behaviour, but I certainly derived pleasure from my protest.

Jan is now attending lessons at art school. I’m confined to watching, admiring from the sidelines. I’m not allowed to study for reasons that come down to the fact that I have no downy little moustache on my upper lip. Good drawing skills are important if you want to get into the academy, but ‘being a man’ appears to be the real craft.

Jan is praised as an artist and he is talented, but it stings to constantly be confronted with what has passed me by, what has been denied to me. He is not even aware of half his privileges. Does he not remember my drawings?

Jan peers at us, then focuses on his work again. I hear him sigh how hard it is to be condemned to a life of art.

It makes me want to laugh. It is remarkable that his paintings are so realistic, that on canvas he manages to capture the edges of reality, but that in the real world he has no sense of perspective.

He may be a masterful painter, but I still have a keener eye.