When the Last German Kaiser Turned Woodcutter in the Netherlands

After the German defeat in World War I, Emperor Wilhelm II sought and got asylum in the neutral Netherlands. On 15 May 1920, he settled in Huis Doorn (House Doorn) near Utrecht, an estate with a lavishly furnished country house, where he would live with his family until his death in 1941. Today, the manor is a museum worth visiting.

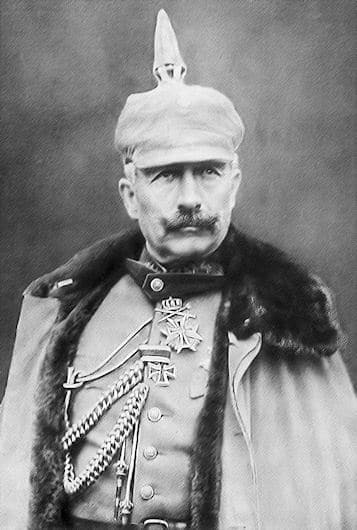

Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany in army uniform, 1915

Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany in army uniform, 1915© Wikipedia

It is a photograph that went all around the world: the German Kaiser Wilhelm II pacing up and down the platform at the Dutch border station at Eijsden in the province of Limburg. The date was 10 November 1918, and the Kaiser had travelled in a convoy with his retinue from the German headquarters at Spa to Eijsden, where the imperial train was waiting for him. The day before, the Republic had been proclaimed in Berlin. The Kaiser had requested political asylum in the Netherlands.

On the platform, local Limburgers and Belgian refugees called him ‘Schweinhund’

and ‘Mörder’. ‘Vive la France!’, they shouted, and ‘Kaiser, wohin? Nach Paris?’ The go-ahead was given after a number of telephone calls and a telegram from Queen Wilhelmina, and the imperial train steamed off to Maarn near Utrecht, where the Dutch Count Bentinck extended hospitality to Wilhelm at Kasteel Amerongen. Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch cabinet would tolerate the Kaiser as a private individual, and that was to remain the official line, in order to pacify both disgruntled populace and angry Allies. Much to Wilhelm’s frustration, Wilhelmina would never officially receive him and never visit House Doorn herself.

German Emperor Wilhelm II lived in Doorn in exile from 1920 until his death in 1941.

German Emperor Wilhelm II lived in Doorn in exile from 1920 until his death in 1941.© Flickr / Hans Splinter

On 28 November 1918, at Amerongen, Wilhelm signed his abdication as German Kaiser and King of Prussia. Heels clicking, a farewell was bid to Seine Majestät. The empire was dead, but Prussia still had a little life left in it. His obedient and devoted wife, Augusta Victoria, who had given Wilhelm seven children, came to join him that day. Wilhelm was to remain Bentinck’s guest not for days or for weeks, but for almost two years.

In May 1920, he finally took up residence nearby at House Doorn, which he had discreetly purchased. Fifty-nine train carriages had transported imperial household goods, furnishings, art and kitsch from the Hohenzollern palaces in Berlin to Doorn. The Kaiser was able to maintain a certain level of grandeur. He was wealthy enough to keep a household of German retainers and – to the irritation of the local nobility – generously remunerated Dutch staff.

Study of Wilhelm II in House Doorn

Study of Wilhelm II in House Doorn© Flickr / Thorsten Hansen

When the Empress died in 1921, she was given a massively attended funeral in Berlin. The Kaiser got married again the following year, to a widowed German princess, Hermine von Reuss. This second marriage, to an overbearing intrigant who was almost thirty years younger than him, was not a popular one. And so, the deposed Kaiser settled into his routine as a redundant monarch who hoped against hope that one day he would be called back to Germany.

The Kaiser with his second wife, Hermine von Reuss, in Doorn, 1933

The Kaiser with his second wife, Hermine von Reuss, in Doorn, 1933© Deutsches Bundesarchiv

He received monarchist visitors at Doorn, including Queen Mother Emma and later Princess Juliana and her new German husband, the money-grubbing Bernhard. The future Queen Beatrix lay asleep in her pram. However, Göring also came to visit a few times before Hitler seized power in 1933. The Kaiser hoped the Nazis would restore him to the throne; the Nazis wanted to secure the support of the Kaiser, and therefore of the Prussian-minded nobles and officers.

Wilhelm did not like the Nazis, though, and soon they no longer had any need of the side-lined Kaiser. In May 1940, when the German soldiers reached House Doorn, the Kaiser gave them breakfast and champagne. When they took Paris, he sent a telegram to congratulate Hitler, whose response was respectful, but cool. In reality, the Kaiser was discreetly being held captive at Doorn – by German soldiers. When, after a woodcutting session, Wilhelm talked to one of those German soldiers, and found that he no longer recognized him, he realized that his world was over.

The Kaiser died on 4 June 1941. The day before, he had welcomed the German invasion of Crete with enthusiasm: ‘Das ist fabelhaft. Unsere herrlichen Truppen!’

Hitler wanted the Kaiser’s body to be taken to Potsdam, as he hoped to pass off as the Kaiser’s successor at the funeral, but Wilhelm’s will stipulated that his body should only be transferred to Germany if the land was a monarchy. And so he was buried in the park at House Doorn. His two wives were laid to rest in the park at Sanssouci in Potsdam.

Funeral of Wilhelm II in Doorn, 1941

Funeral of Wilhelm II in Doorn, 1941© Deutsches Bundesarchiv

It was a glorious day at Doorn: Kaiserwetter. Those who followed the coffin included Seyss-Inquart, the Reichskommissar of the occupied Netherlands, and Admiral Canaris, the head of the German military intelligence service. Canaris was later executed at Flossenbürg concentration camp after the failed assassination attempt on Hitler, while Seyss-Inquart was executed in Nuremberg after the war. There were swastikas at the funeral, which the Kaiser would not have wanted, and a wreath from Hitler.

Mausoleum of Wilhelm II at his estate in Doorn

Mausoleum of Wilhelm II at his estate in Doorn© Flickr / Hans Porochelt

The family elected not to open the mausoleum at House Doorn to visitors. Peering through the window, I catch a glimpse of the Prussian flag with its black eagle draped over a casket. I walk around the park: the horses, the deer, the graves of the five imperial dogs; the spot where the Kaiser, methodically, obsessively, needlessly, turned thousands of trees into stumps; the majestic trees in the watery autumn sunshine. I wander through the castle, past the dinner services and the silver, the tapestries and the snuffboxes that once belonged to Frederick the Great, a role model for Wilhelm, his epigone. The abundance of knickknacks and bric-à-brac is wearying, but the portrait of the delightful Queen Louise of Prussia, who charmed Napoleon at Tilsit, hits me square in the face: this woman married at seventeen, gave birth to ten children, and died at the age of thirty-four.

Dining room in House Doorn

Dining room in House Doorn© Flickr / Sebastiaan ter Burg

I see the dining room with its table laid for eternity, where no one will ever dine again, and the special fork with three tines, one of which also served as a knife for a Kaiser who had a withered left arm. I amble through the bedrooms that once belonged to the Kaiser and his two wives, the smoking room, the study, the library of this amateur archaeologist; the Empress’s modern toilet, neatly concealed in an antique closet.

This is a place where people lived. Survived. Maintained the appearance of a court in exile. With a Kaiser who read aloud from the Bible every morning to his assembled staff. And who then went out for a walk, to chop wood, eat lunch, have a siesta, answer correspondence from all over the world, dine from plates that were whipped away the moment His Majesty had finished eating. A routine designed to provide meaning in a meaningless life.

The estate of House Doorn

The estate of House Doorn© Flickr / Dirk-Jan Kraan

House Doorn, confiscated after the war, is now the property of the Dutch state. Subsidies have recently been scaled back, but an army of volunteers keeps the place open and running. Whatever happened to the Kaiser’s large financial legacy remains a mystery. The House of Orange, the Dutch state, the House of Hohenzollern and the banks provide no clarity. I came to Doorn with the notion that I would find one of the few WWI lieux de mémoire on Dutch soil. However, what I encountered was more like a trou de mémoire of the Great War, and I walked around, somewhat bewildered, within a lieu de mémoire

of European absolutist empires and monarchies, perhaps a last echo of the Ancien Régime, surviving in a form that is both tragically ironic and slightly grotesque. After all, the grandmother of Wilhelm (who remained “our Willy” to the British branch of the family) was Queen Victoria and the last tsar was his first cousin by marriage. House Doorn? It’s most definitely worth a visit.