Karl Marx Wrote Global History in Brussels

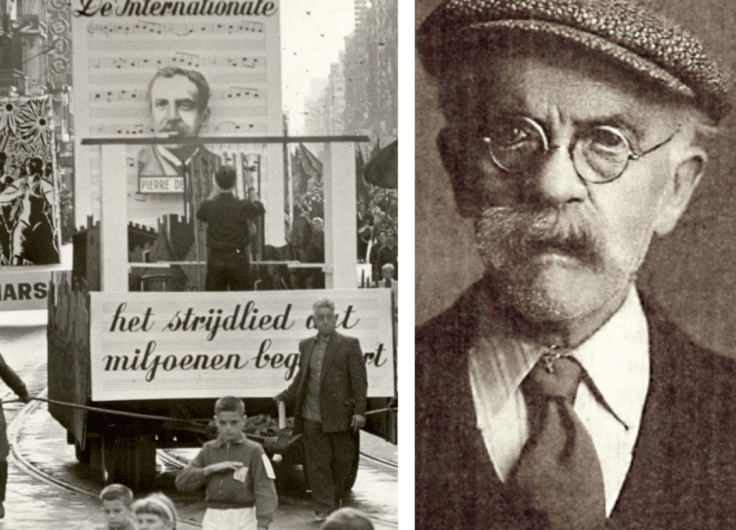

Having been expelled from Germany and France because of his controversial views, Karl Marx moved to Brussels in 1845, when it was a haven for all sorts of revolutionaries. He lived there with his family for three years. The Belgian capital marked a turning point in the German philosopher’s life. It was there Marx worked with his close friend Friedrich Engels on his Communist Manifesto. ‘From Brussels, he started a revolution that would radically change the world,’ writes historian Edward De Maesschalck in his book on Marx’s Belgian years.

The first important milestone in Karl Marx’s life was Berlin. In 1836, he had switched from studying law at Berlin university to philosophy. There he was introduced to Georg Hegel’s ideas, which left a deep mark on him. The philosopher believed the history of humankind to be dynamic, and that leaps are regularly made as a result of internal tensions, conflicts and clashes that may lead to the explosion of a revolution, the process we know of as thesis, antithesis and synthesis, which Hegel called “dialectic”. It is clear that Marx applied this method in his vision of human development.

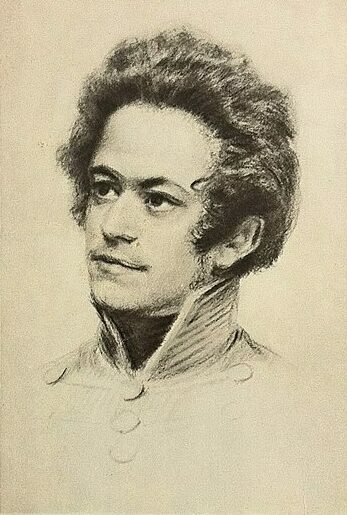

Young Marx, before 1840

Young Marx, before 1840© Wikipedia

After finishing his studies, in 1841, the Doctor of Philosophy moved to Bonn, where he hoped for an appointment as a university lecturer. When that did not materialise, he turned to journalism. In Cologne, Marx became editor-in-chief of the Rheinische Zeitung, a daily newspaper for progressive liberal readers. Under his leadership, the newspaper became increasingly radical, and at the same time Prussian censorship became stricter, until the newspaper was eventually banned by the government.

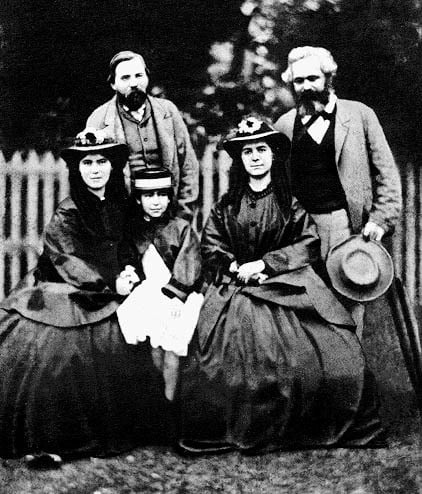

Marx married Jenny von Westphalen (1814-1881), the daughter of a baron.

Marx married Jenny von Westphalen (1814-1881), the daughter of a baron.© Wikipedia

In the summer of 1843, Marx married his childhood sweetheart Jenny von Westphalen, not only the ‘prettiest girl’ in his native Trier, but also the daughter of a baron. She accompanied her husband everywhere.

A few months later, Marx was asked to become editor of the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, as a result of which, he and Jenny had to move to Paris. But the yearbooks were a failure, only one edition was ever published. After this fiasco, Marx worked as a contributor to the journal Vorwärts. But this too turned out to be disastrous for him. Due to an article applauding an attack on the Prussian King, the journal was banned, and all its employees were expelled from France. Once again, the family had to move. Marx decided to go to Brussels with his wife and first child Jennychen, since many Germans lived there and, moreover, free speech was guaranteed by the progressive Belgian constitution. By this time he was 26 years old.

While he was in Paris, Marx had met Friedrich Engels, the son of a German textile manufacturer, who had just returned from Manchester, where his father owned a cotton mill. There, Engels had been confronted for the first time with the crushing reality of the industrial revolution. He published a prophetic book about it, The Condition of the Working Class in England, in which he conjured up for his German compatriots an image of a distant future that already actually existed in England. For Marx, this was a revelation. The industrial revolution and its nefarious effects on the workers soon became an essential part of his vision of human development.

Engels donated the proceeds of his book to Marx, which was very convenient, as Marx had to survive in Brussels without his income as an editor. He was hoping for an inheritance from his late father, but that might take some time.

Friedrich Engels supported the Marx family financially.

Friedrich Engels supported the Marx family financially.© public domain

Brussels, a vibrant city

At the time, Brussels was a city of about 124,000 inhabitants, while the rapidly growing suburbs (Ixelles, Saint-Josse-ten-Noode and Molenbeek-Saint-Jean) already had a combined population of 40,000. For Marx, Brussels was ideally located between the three great building sites of socialism (Germany, France and England) and there were excellent connections by train and the Ostend-Dover mail boat (as of 1846). But Brussels itself was also instructive, as a rich upper class lived there alongside a mass of poor people who, having moved into the city, had been ruined as a result of the import of cheap, mechanised products from England. On top of this, there was the Potato Famine of 1846 and grain shortages in 1847. Poverty in Belgium was at an all-time high, which reinforced Marx’s belief that revolution could not be long in coming.

In nineteenth-century Brussels, a rich upper class lived alongside a mass of poor people.

In nineteenth-century Brussels, a rich upper class lived alongside a mass of poor people.photo taken from the Bulletin de l'Association belge de Photographie, vol. 13, no. 4, 1886, p. 149.

Marx lived in various places in Brussels, first in Avenue Pacheco, not far from the cathedral; then in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode near the Leuven Gate (Rue de l’Alliance 5), where his second child, Laura, was born; and later, in Ixelles (Rue d’Orléans 42), where his son Edgar was born. The family was assisted by Helene Demuth, a maid given to them by the Baroness von Westphalen. The maid looked after the children and the household, so that Marx’s wife Jenny could devote herself to copying his writings, which were completely illegible for outsiders. When their money ran out, the family would live temporarily in the cheap boarding house Le Bois Sauvage next to the cathedral. They stayed there three times.

Marx had been granted a residence permit in Brussels on condition that he promise “not to publish any writings on the present political situation”. He agreed to this because he sincerely intended to take advantage of his time in Belgium to study and gain clarity in his ideas. Nonetheless, the secret service kept a constant eye on him, although for the time being they put no obstacles in his way.

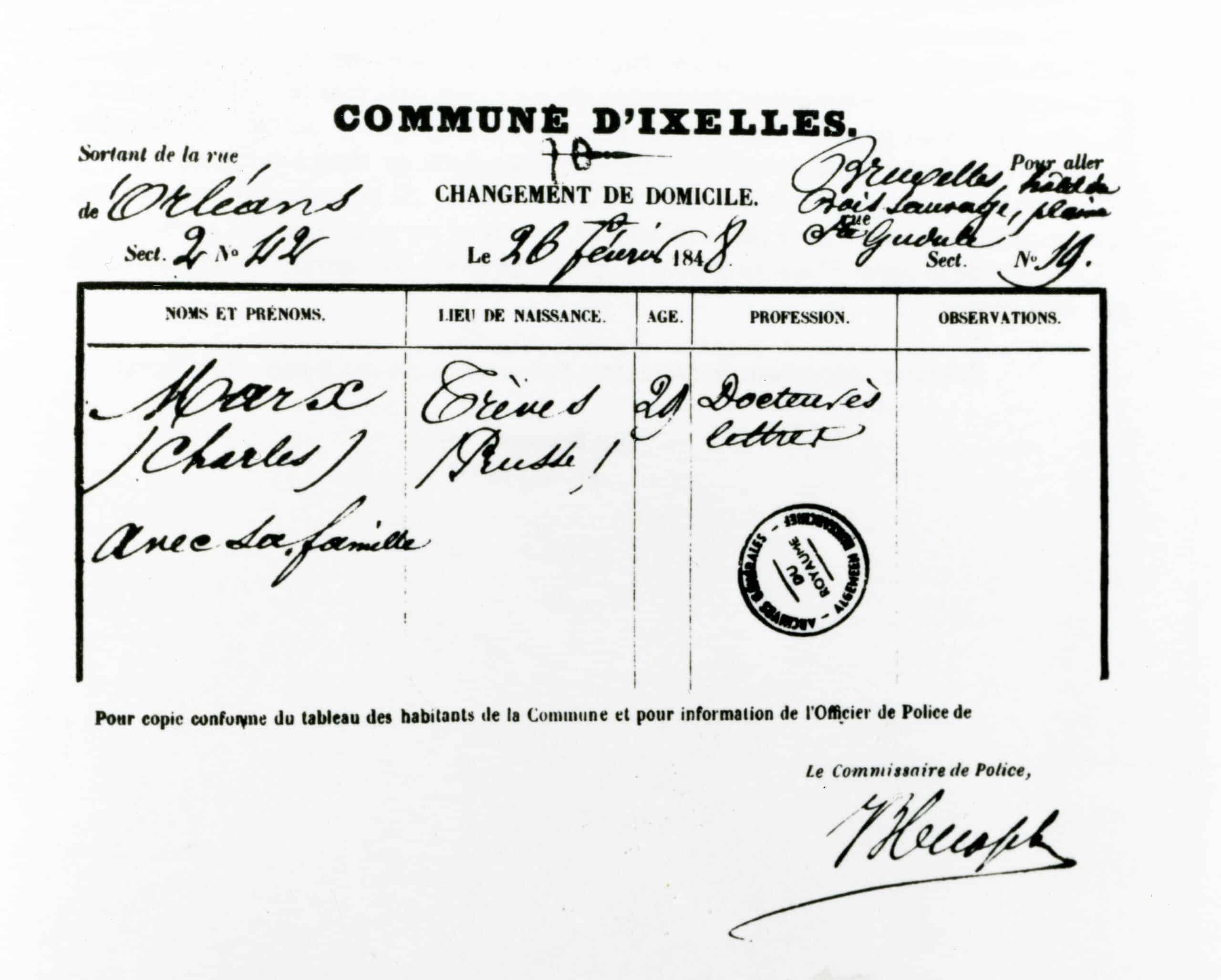

An administrative document mentioning Karl Marx's move from Ixelles to Brussels

An administrative document mentioning Karl Marx's move from Ixelles to Brussels© Source: Brussels, General State Archives, Public Security Administration. Alien police, file 73 946, 23 (item 20)

Feuerbach's influence

During this period, Marx immersed himself, with Friedrich Engels, in the then dominant ideas of the German philosophers, in particular those of Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872). From September 1845 to April 1946, they worked together on The German Ideology, a book they never published but which laid the seeds of materialist historiography. Feuerbach argued that matter was primary and the spirit secondary! He applied this theory to religion, as belief in the hereafter was clearly the creation of people who sought solace in a heaven because their lives on earth were so difficult. Marx also applied this line of thought to domains other than religion. The class that rules over matter (the production factors) creates the ruling ideology as well. If the workers were to capture power over matter, their ideology would become dominant. The book’s conclusion, Marx’s famous eleventh and final thesis against Feuerbach’s teachings, reads as follows: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.” It is this thesis, written in Brussels, that is engraved on Karl Marx’s tomb in Highgate Cemetery.

Communist Correspondence Committee

In the mid-nineteenth century, there were quite a lot of communist prophets roaming round Europe, often hounded by their governments. Some developed grand theories, while others campaigned. In an effort to align all these social reformers Marx, with his friend Engels, set up the Communist Correspondence Committee, which would confer by letter with people all over Europe. Its headquarters were in Brussels, at the home of Philippe Gigot, a young Belgian communist who lived opposite the Church of the Sablon (Rue de Bodenbroeck 8).

Marx was an outspoken supporter of the English Chartists, led by George Harney, since they advocated universal suffrage for men. After all, Marx believed in the conquest of the state as the way to improve the lot of the workers. He rejected quibblers like Wilhelm Weitling, a communist agitator who made his living as an itinerant tailor, because they were pushing for revolution with no idea of where it would lead. Marx’s blunt statement during a confrontation is still famous, “Ignorance has never helped anyone“.

In an effort to align all social reformers Marx, with his friend Engels, set up the Communist Correspondence Committee

Marx was also a declared opponent of the True Socialists, whom he considered too soft – men like Hermann Kriege, who emigrated to America in 1845 and published a weekly in New York called Volkstribun. The True Socialists explicitly renounced class struggle and violence, but appealed passionately for solidarity, brotherhood among people, and love. Marx pursued Kriege all the way to America with a pamphlet mocking this ‘apostle of love’. Kriege was in turn defended by Frenchman Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865), who advocated the introduction of production cooperatives. However, because he did not believe in the conquest of the state, Marx rejected him too.

The course of history

In 1847, Marx gave up studying for a while and took up politics. He became the editor of a German newspaper in Brussels, the Deutsche Brüsseler Zeitung, which regularly took radical positions. This was a violation of the agreement he had previously made with the Belgian state. However, although he was watched more closely than ever, he was still left in peace.

Karl Marx celebrated New Year's Eve 1847 at “De Zwaan” with the "Deutscher Arbeiterverein" and the "Association Démocratique".

Karl Marx celebrated New Year's Eve 1847 at “De Zwaan” with the "Deutscher Arbeiterverein" and the "Association Démocratique".© Wikipedia

That same year, Marx also founded the Deutscher Arbeiterverein, a public association for German workers in Brussels, which was to serve as a shortlist for hardened communists. Political education was given there, but occasionally the ladies were allowed to come along as well, and there was partying and dancing, such as on New Year’s Eve 1847, at the Inn De Zwaan (The Swan) on the main square, or Grand Place. Today, a plaque on the façade commemorates Marx’s passage there.

Marx was also the co-founder of the Francophone Association Démocratique, an international association of progressive thinkers based in Brussels. Its president was a Belgian, Lucien Jottrand, a progressive lawyer and Karl Marx was the vice-president. On 9 January 1848, Marx gave a now-famous speech at the Association Démocratique

on the issue of free trade. He began his speech – as expected – with a frontal attack against free trade. He outlined a truly apocalyptic perspective of what would happen in a world in which free trade triumphed. In future, exploitation would no longer remain locked in individual countries, but would be exported across borders and eventually worldwide. In fact, he said, free trade was the road straight to social revolution. But then Marx ended with the surprising statement that he was an advocate of free trade.

The Communist League

For Marx, the Communist Correspondence Committee was just one step on the way to the real goal, the formation of a homogeneous communist party that could take the lead at the outbreak of a possible revolution. In June 1847, the “Communist League” was founded in London with branches in other countries, including the Belgian capital. To discuss the programme, Marx went to London in the autumn of 1847, where the debates lasted a full ten days. Marx won the argument, and his main principle was inscribed as the first item in the new statutes:

Cover of the original 1848 London edition of the Communist Manifesto

Cover of the original 1848 London edition of the Communist Manifesto© Wikipedia

“The aim of the League is the overthrow of the bourgeoisie, the rule of the proletariat, the abolition of the old, bourgeois society based on class antagonisms and the foundation of a new society without classes and without private property.”

In addition, Marx was given the task of writing the League’s programme, the so-called Communist Manifesto, as soon as possible. This he did in the Brussels suburb of Ixelles, after which the piece appeared in print in London, in February 1848.

Marx expelled

The same month, Marx received a bill of exchange worth 6,000 francs from his mother in Trier, intended as an advance on his late father’s inheritance. From then on, the Belgian security service kept a closer eye on him than ever. Coincidentally, a few days later, on 24 February, the revolution broke out in Paris. Keen to get to Paris as soon as possible, Marx gave notice that he was leaving his house in Ixelles and settled with his family in the Bois Sauvage boarding house in Place Ste Gudule. Meanwhile, London moved the Central Committee of the Communist League to Brussels. When the Association Démocratique made an approving statement about the revolution in France, the Belgian security service took the decision to have Marx expelled. A bailiff served him with the expulsion order on 3 March, giving him 24 hours to leave the country. That evening, the Central Committee met at Le Bois Sauvage and declared that the Communist League would move to Paris.

Karl Marx's arrest in Brussels. Sketch by N. Khukov, 1930s

Karl Marx's arrest in Brussels. Sketch by N. Khukov, 1930s© public domain

Alerted to the gathering at the boarding house, the police commissioner sent a patrol there. They raided Le Bois Sauvage at one o’clock in the morning, only to find that the birds had already flown. Storming up the stairs, the police first mistakenly burst into the room where Jenny Marx, the maid and the other children were sleeping, before entering Marx’s room, where he was busy packing his bags. Fumbling to get his deportation order out of his jacket pocket, Marx mistakenly handed over the Central Committee document. He was arrested and taken to the prison behind City Hall.

Jenny von Westphalen went outside, alarmed, and encountered a policeman, who offered to take her to her husband. As a result, she, too, ended up in prison. There she was treated rather brutally and had to share the room with some prostitutes, which later caused a big fuss, as she was a woman of standing. An enquiry was ordered, parliamentary questions were asked, and in the end, the smallest cog in the wheel had to pay for this charade. The policeman responsible was sacked for misconduct.

Brussels’ role

That was the end of Marx’s stay in Brussels. After a detour via Paris, Berlin and Cologne, Marx finally arrived in London in 1848, where a new chapter in his life began with the founding of the First International and the writing of Das Kapital. He was to die there in 1883, at the age of 64.

Marx lived in London for 33 years and in Brussels for only three. Yet that short period in the Belgian capital proved to be an important turning point in his life. He arrived as a socially committed scholar, seeking clarity and finding the key to a better understanding of human history. In Brussels, Marx emerged as a revolutionary with a mission. It was in Brussels, too, that his view of materialist historiography was born, and in Brussels that Marx wrote his Communist Manifesto, a landmark and a monument in a changing world.