Kasper Bosmans: ‘Each of My Artworks is Like an Onion’

Kasper Bosmans’ career (b. 1990, Lommel) is soaring, and the international art scene has taken notice. Blessed with a fresh perspective, this young Brussels-based artist looks into various art-historical motifs, elements taken from heraldry – which he considers folkloric witticisms –, and different socio-economic themes. Combined, they culminate into colourful paintings and art installations that playfully merge together.

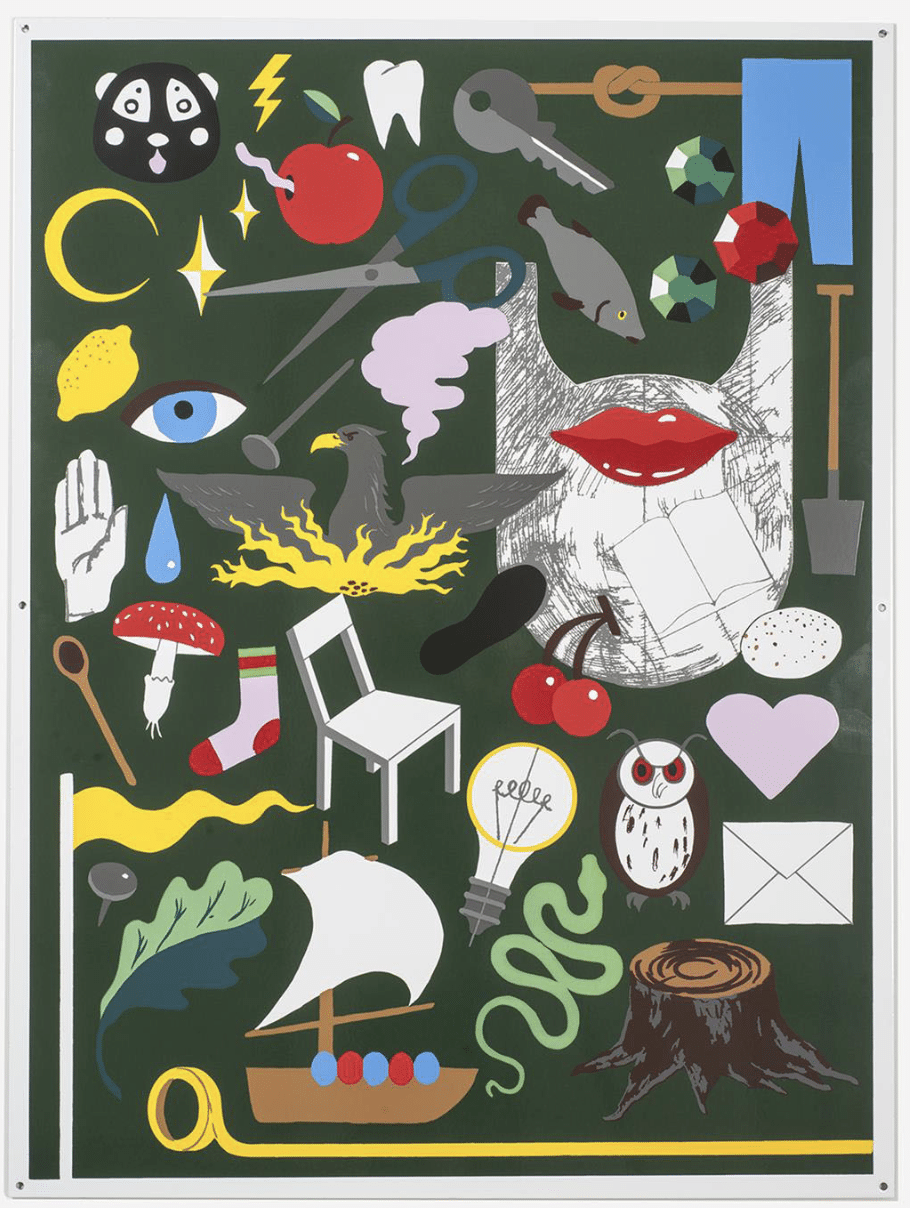

In 2013, Kasper Bosmans started to paint legends on small boards, as his alternative to the information that is usually displayed on museum wall labels next to works of art. These tiny, mysterious little panels are decorated with abstracted drawings full of symbolism, inspired by traditional heraldry. In these small paintings, Bosmans manages to combine stories and associations that – at best – generate enigmatic images. The artist perceives them as a tool to access his art, like a guide, and a substitute for a curator’s or copywriter’s words accompanying the artwork.

Enamel Legend: Do Be Do (Dark Green), 1990 & Legend: Model Garden, 2016

Enamel Legend: Do Be Do (Dark Green), 1990 & Legend: Model Garden, 2016© Gladstone Gallery, New York/Brussels

Hilde Van Canneyt: You will often use flags, symbols and emblems. Does this mean you find yourself peering over dusty old books with a magnifying glass each night?

Kasper Bosmans: ‘Yes, I actually rifle through many old books at night. I tend to find them online. It is often easier to find books on the Internet than you would in a library. To me, that is just such a lovely and accessible way of doing it. I also buy a lot of books, and often visit antiquarian booksellers. I have, however, noticed I buy fewer and fewer art books, and will increasingly use things that are not related to art.

I can be inspired by basically anything. A while ago, a friend of mine had found a book about Viktor Schauberger, a kind a pseudo-scientific esoteric Austrian forest ranger who died in the fifties. He came up with very interesting theories about the way we should use water – a type of mystical hydrodynamics. Although I am not using it right away, I am sure it will come in handy one day.

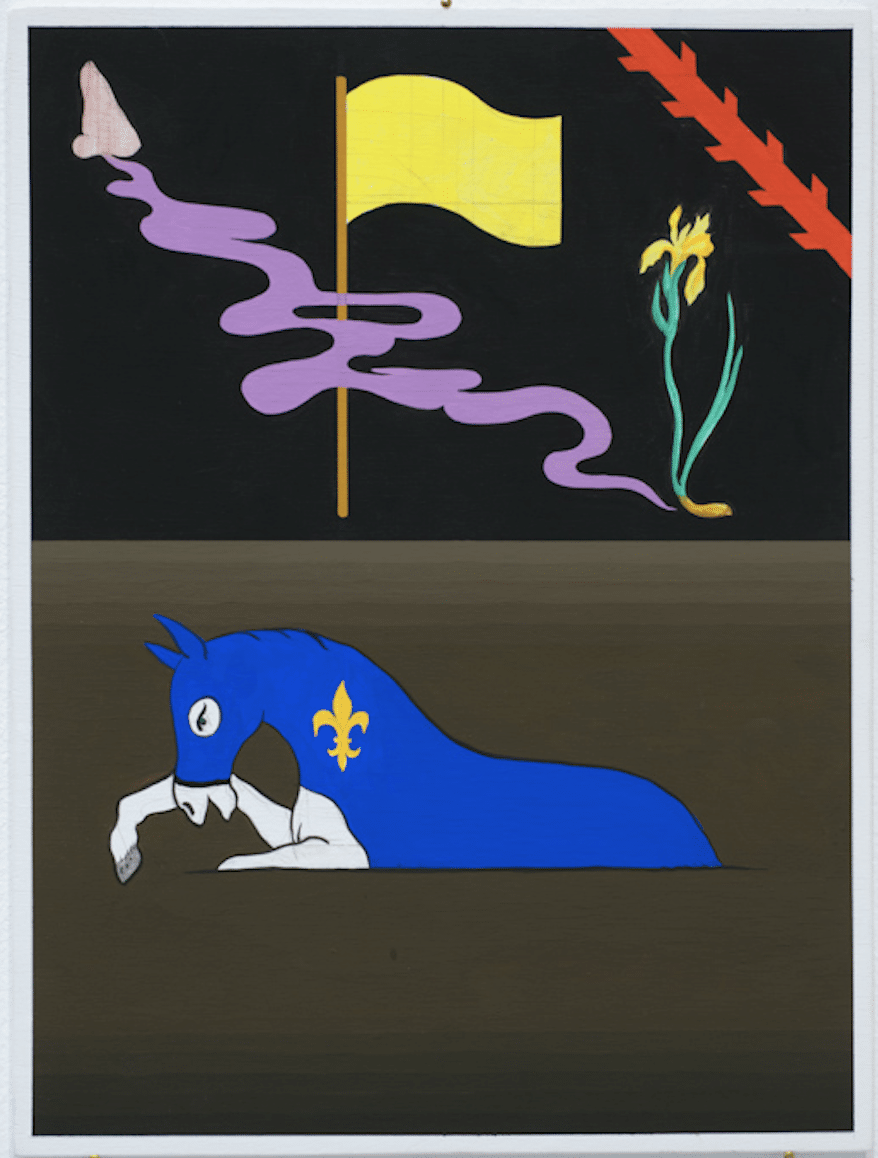

In addition, I collect books about heraldry, and I love to pore over recipes. I can find inspiration by doing that. Or take, for instance, 18th-century France’s political history. The origins of the French Revolution, and which information was used for it to finally happen, is extremely fascinating. In the Netherlands, the Patriot Revolt broke out around 1780. This revolt inspired both the American War of Independence and the French Revolution. I am intrigued by facts like that. As soon as you start digging into those stories, you will come upon other topics. The more specific the information is you come across, the more you can uncover about everything we do today, about how we think, talk, live and eat.’

Kasper Bosmans

Kasper BosmansSo, by shedding light on history’s segues, you also provide insight into our contemporary world.

‘Dealing with something that happened a long time ago, allows me to be quite inaccurate. That kind of inaccuracy leads to poetic freedom, for it is possible to overanalyse things. As an artist, it is my job to view the world from a poetic perspective. However, I am not claiming everything is peaches and cream, but it does take a certain eccentric approach. I believe I should not be changing form, but rather rethink content. I am talking about an innovative old-fashioned method.’

When you read, you tend to take a lot of notes. I read somewhere, however, that you will never consult those notes afterwards.

‘As soon as you are underlining text, you start to memorise it. The act of underlining itself is important to structure ideas in your head. In a way, my paintings with legends work in a similar manner. I make them and am able to memorise everything I came up with afterwards, which anecdotes, and which visual bridges can be built.’

Decorations, 2016

Decorations, 2016© Witte de With, Rotterdam

You were invited to exhibit at CIAP, located at the former building of the provincial council in Hasselt, where you showed your work in old, existing spaces. That is a far cry from Witte de With in Rotterdam – a white cube – where you also had a solo exhibition.

‘In terms of content those exhibits were quite different. At Witte de With, I was asked to really think about their history. The idea there was to create a genuine visitor experience. The works on display were mostly murals, as I wanted to make people experience the history. At CIAP, however, my approach was rather different, as that location had previously been a political institution.

CIAP is located in an eclectic little city palace. This brings along a number of difficulties, as the space is listed. You cannot simply go around hanging things on walls. I use aesthetics to invite visitors to think differently. I, for instance, kept one room extremely austere and bare. Sometimes, when you do not fully show them, spaces like that will become even more impressive. What is most important to me is the ability to create an experience using my work, but allowing it to exist as is. This can be quite the jigsaw puzzle, though.

With my own paintings I do pretty much the same thing: I try and make a well-balanced composition in which content and form merge together seamlessly. I use that approach throughout the exhibit. Actually, somewhere in the back of my mind, I try to accomplish that with my entire oeuvre. To me it is important to, occasionally, create art I do not touch myself, and that is executed by others. I believe that is just as valuable as work I “fondled”, and created myself from start to finish.’

Legend Decorations, 2016 & Legend Sint Rombout + Vitiligo, 2016.

Legend Decorations, 2016 & Legend Sint Rombout + Vitiligo, 2016.© Kasper Bosmans, Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles & Gladstone Gallery, New York/Brussels

Along with the Rotterdam exhibit came a book in which you referred to the old masters. In it you write, ‘As an artist you find yourself stealing all the time; for that reason this crime actually symbolises the way I appropriate things, rather than my critique of them.’

‘It is all about editing, and design as well. You might have access to the source material, but how will you translate it? How can you come as close to that as possible? Is it by using the feathers of that particular bird, or a fragment of the Royal Palace walls in Brussels, or the scales of a goldfish, or a chunk of butter, or a pair of pink socks, or an 18th Century pamphlet, or…? What seems most efficient to me? A single fragment, but how will I indicate boundaries? Those decisions are of an aesthetic nature, and I will consider first of all what will visually work for you, the visitor.’

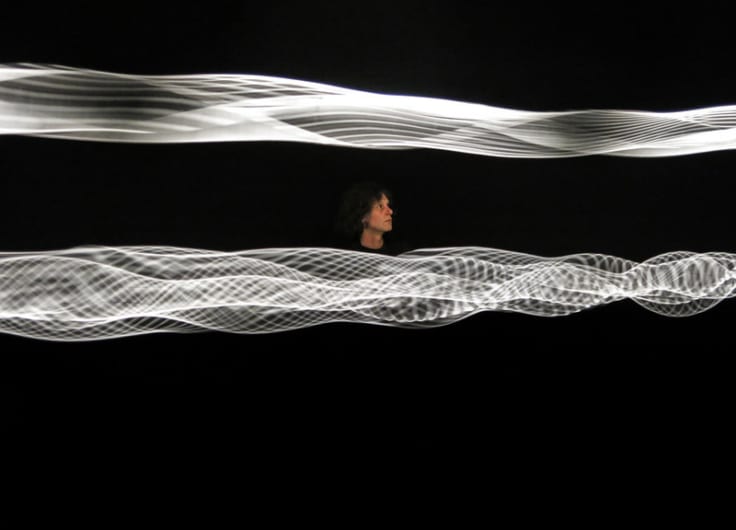

Amber Room, 2018

Amber Room, 2018© Gladstone Gallery, New York/Brussels

When you have an exhibition coming up, I assume you try and combine brand-new creations with existing work. You continue to build on your oeuvre.

‘I produce as much new work as I can. To me, that is what is most exciting. Nevertheless, sometimes you come across leads that might be relevant at that time. I tend to create series, such as Star Chamber and Amber Room, two decorative rooms with a politically charged meaning. Those series were also transformed for the Venice Biennale. There, they had to be displayed differently, and the same goes for my exhibits in the Ukraine and New York. Either way, I will create a new set of legends for each exhibit.’

You think it is important for children to also connect with your work. You purposely rely on a clear aesthetic.

‘Isn’t that how the world works? If you and I were to go to the Grand Place in Brussels, we would come across a lot of visual information I would not be able to explain to you and vice versa. However, I do not believe this should frustrate us, seeing we are able to educate ourselves on that. When faced with the Venus of Willendorf why should we shout out, “That is a goddess”? No, those are just interpretations. Still, I do not think all the hard work should be done for you. The world is a complex place. Why can’t art be like that as well? All art has a Marsupilami tail.’

You do not want your art to remain passive. In other words, visitors are expected to work with it.

‘Each of my artworks is like an onion. What I appreciate, and try to accomplish – and what frustrates me at the same time, especially when it comes to commercial spaces – is that I stuff so much information and anecdotes into my work, it almost causes visitors indigestion. There aren’t many aesthetic decisions whose origins do not lie in content. An elevator pitch, during which you need to explain the ideas behind your work in a matter of minutes, well, I don’t have to do that at all. I enjoy the fact that there are many layers and openings, and only the tip of the iceberg is revealed. My work is a visual ready meal, but I take pleasure in filling it with oodles of information. Not everything needs to be explained.’

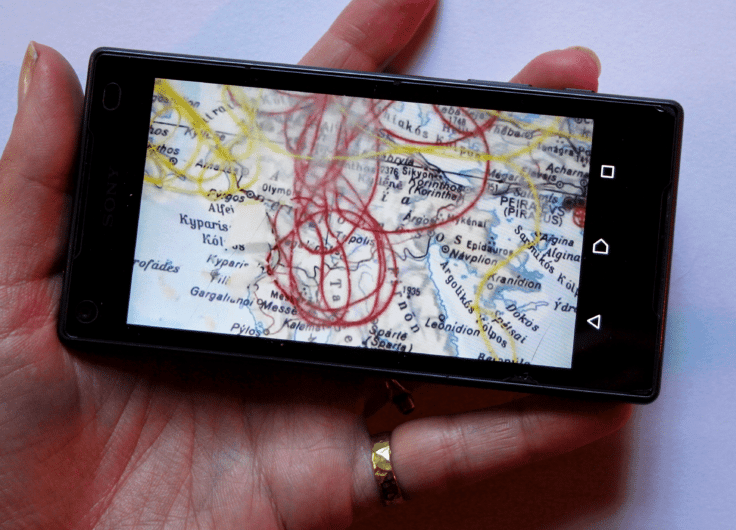

T.O. Chip Log (Ebstorf), 2018

T.O. Chip Log (Ebstorf), 2018© Gladstone Gallery, New York/Brussels

You have compared your work to that of a composer. Is that because you rely on a similar method?

‘Take, for instance, Mahler. He refused to write systematic music, so he never illustrated stories, as Wagner did in his operas. His work is not completely abstract either, like Brahms’ is. Mahler worked in citations; you could say he is a kind of romantic postmodern composer. He would repeat a motif, and would add a tiny variation. He was also able to establish moods using certain pieces that would become so abstract you sort of get lost a little, as if you were to sink down into a sofa, or have a seat on an icy chair. I enjoy those mood variations. Not everything needs to illustrate something else, nor should everything be completely abstract, but rather somewhere in the middle. I truly enjoy that balance, and that’s what I appreciate in other artists’ creations.’

I read that your mind is at its most creative when you are not doing anything at all.

‘I remember this great conversation I had with Richard Tuttle, a post-minimalist and a lovely artist. He said, “What frustrates me on a daily basis is the fact that I have to get up and still need to make that work of art myself, since nobody will do it otherwise.” Of course, by saying this he is paying himself a compliment as well. I love that, because I would prefer not to do anything myself. I rarely come up with new ideas when I am busy doing something. It does happen more when I paint or draw, as those activities are more straightforward. But I do enjoy discussing my work.’