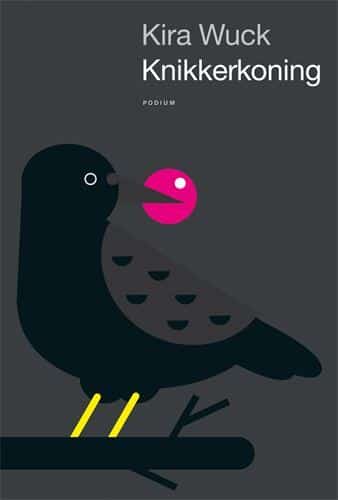

‘Knikkerkoning’ by Kira Wuck: Detached Tale of a Wild Life

With the patently autobiographical Knikkerkoning (Marble King) Kira Wuck paints a picture of her promiscuous hippy parents. It is not the sentiment but the aloof tone that makes this book special.

Nobel Prize winner Bob Dylan recently celebrated his eightieth birthday. It is fitting to highlight a debut that has a text by Dylan as its leitmotif. ‘Well, the emptiness is endless, cold as the clay / you can always come back, but you can’t come back all the way,’

reads the dedication. A line from Mississippi, a song in which Dylan has no regrets apart from having lingered one day too long in accursed Mississippi.

Dylan appears again a few more times in Knikkerkoning (Marble King), the debut novel by the Dutch writer Kira Wuck (b. 1978). After all, it is the rebellious ’70s, in that part of Amsterdam populated by provos and hippies, where nobody seems to have a steady job and everyone is on drugs, including Otto, one of the book’s main characters. To scrape some money together, he busks in the underpass under the Rijksmuseum, singing songs by Dylan – whom he considers the only real father he has ever had. His biological father, an East-Indies colonial soldier, had such a spartan method of bringing up his children that Otto fled the family nest in Renswoude as soon as possible, towards freedom: Amsterdam.

It is there that he meets the red-haired Anne, as small as she is flamboyant. She is also running away; from an alcoholic father she sees too little and an overprotective mother who gets in her hair. Anne is Finnish, and the excellent school report card that gets her a flight to Amsterdam is her definitive escape route from cold Finland.

There is something aloof about the novel, as if the daughter wants to tell her parents’ story with an almost clinical matter-of-factness

Life in Amsterdam is not all roses and moonlight for Anne and Otto, on the contrary. They fall under the spell of Rob, a sort of guru who preys on lost souls to take advantage of them. Moving from drug den to squat, they sleep among rats and must daily busk and beg their way to buy something to eat. Or, in Anne’s case, to drink, since she clearly inherited her father’s alcoholic genes.

There is nothing remotely romantic about their quick marriage; antithetical to the zeitgeist it is quite the business transaction. It means Otto is released early from prison, and that Anne receives a Dutch passport, which will finally, she hopes, allow her to start studying. But as unstable and unconventional as their marriage is, the two eventually come to love each other.

Kira Wuck

Kira Wuck© Peter van Tuijl

The result of that love is Jane, the daughter through whose eyes we relive the tale of Otto and Anne. Jane had almost not been born; Anne changed her mind as she was heading to the abortion clinic. Because someone throws themself in front of her train, she is delayed, and in that delay, Anne is entertained by a cheerful toddler. That’s how close life and death are.

There are more of such beautiful, subtle reflections in Knikkerkoning and Wuck regularly returns to certain images. But there is also something aloof about the novel, as if the daughter wants to tell her parents’ story with an almost clinical matter-of-factness. Once you get into the flow of the book, it has a mesmerising effect. Despite all the misery, despite all the poverty, despite all the pain, it is precisely this detachment that makes you feel close to Otto and Anne. As though you are reading their diary.

Wuck not only paints the picture of a relationship, but also of a generation

In this way, Wuck not only paints the picture of a relationship, but also of a generation. The romanticised image of free-spirited hippies is seriously adjusted. There was above all much misery, much abuse, much fleeing from debt collectors, and a lot of anxiety. Both Otto and Anne know the worry of not belonging, the angst that seems to consume an entire generation. Few great ideals about a new society feature in this novel, even the Hare Krishnas do not appear to act entirely in good faith.

Kira Wuck makes no secret of the fact that she based this book on the lives of her parents, whom she herself lost quite young. The story ends with Anne’s early death, from an overdose of alcohol and pills, a mix that eventually became her

Mississippi. The epilogue is beautiful. Wuck describes different ways to view that death, and how Anne perhaps, on that last night, dreamed of doing everything differently starting the next day. It wasn’t to be, but the thought is comforting.

An excerpt from 'Knikkerkoning', as translated by Paul Vincent

pp. 87-88

ANNE’S FIRST WEEKS IN AMSTERDAM

Anne wakes up with a thick head and has no idea what she did yesterday. Actually, she can remember scarcely anything about the recent period in Amsterdam. There is a party somewhere almost every evening. She regularly wakes up in a strange place. And because she can scarcely stand the intense morning light sober, she leaves as soon as possible. It’s rotten, she thinks, how reality can force itself on you.

Today she is at home at any rate. She recognises the canal she is looking out on and the chestnut tree announcing the end of summer. Birds call to each other from behind the leaves. Soon they will go, leaving everything behind. Anne is lying in a small side room on a thing camp mattress. Her hair is hanging around her head in tangles, she has not brushed it for days. When she realises that the door is locked, she starts banging on it with her fists.

‘I thought you’d never wake up,’ she hears Ron say on the other side of the door.

‘Let me out,’ she shouts.

‘I’ll get the key, just a moment, darling.’

When he has opened the door, he says that last night she was like a rabid dog. ‘You were so loud I couldn’t have a conversation. And you know how fond I am of remaining coherent. Besides, you kept turning up the volume control of the record player, started dancing wildly and knocked my collection of Indian gods off the cupboard.’

Anne starts laughing. ‘Sounds like s good evening.’

Ron looks at her seriously. I thought alcohol would help relax you, but we’ll have to think of something else.’ He takes her hand, plants a kiss on it and stuffs some money into it. ‘Buy yourself a nice dress, I want to introduce you to someone tonight.’

‘Tonight? I had a quiet evening in mind.’

‘There are men who would pay at least three hundred guilders to spend a night with a beautiful lady like you.’

Anne gives Ron a questioning look. She can scarcely imagine, she feels far from attractive.

It’s time we looked for something for you that suits you. And you really must cut down on the booze.’

‘Yes, Daddy,’ says Anne.

Her fears, which keep her in check during the day, melt away thanks to the alcohol. But the worse she sleeps because of it, the more they rear their heads the following day.

Kira Wuck, Knikkerkoning, Podium, Amsterdam, 2021, 208 pp.