There is a new Kortrijk emerging that has nothing to do with the Battle of the Golden Spurs or flax grown along the banks of the river Lys. Once mockingly called ‘the Dallas of Flanders’, the West Flemish city boasts a vivid music scene and is now hoping to win the nomination for European Capital of Culture in 2030. ‘It could happen,’ according to British journalist Derek Blyth who observes a city in transformation. ‘Kortrijk has come a long way since 1302.’

I was hoping for something impressive as I arrived in Kortrijk. The city is famous for a battle fought outside its walls on 11 July 1302. Every patriotic Flemish person knows the story, all about the weavers who came from Ghent and Bruges, the arrogant French knights, the golden spurs hanging in the church. I met a man in Bruges once who told me the whole story as if it was fresh in his mind, something he had seen in his youth.

The Battle of the Golden Spurs may have happened more than seven centuries ago, at the start of the period Barbara Tuchman called ‘the calamitous 14th century,’ but is part of the Flemish national story, like Gettysburg in the United States, or Agincourt in English history books. It gives the Flemish an identity, a national day. It’s important. I get that. And so I wanted to see what they had done with the battlefield.

The Groeninge gate and Groeninge monument were erected to commemorate the 600th anniversary of the Battle of the Golden Spurs.

The Groeninge gate and Groeninge monument were erected to commemorate the 600th anniversary of the Battle of the Golden Spurs.© Tourism Kortrijk

It’s not easy to find. I looked on the excellent tourist office website under ‘History and Heritage’. Nothing about the battle. I tried the internet. An article mentioned the Groeninge gate, a Neo-Gothic triumphal arch put up to mark the 600th anniversary. And so I got Google maps to take me there.

The arch was promising. On the top, three Flemish flags fluttered in the breeze. A path led through a park to a traffic roundabout. In the middle, a romantic gilded statue representing the Virgin of Flanders, a symbol of the hard-won freedom. She holds aloft a spear while restraining a roaring lion. The monument marks the site of the battle where some 9,000 French troops fought a roughly equal number of Flemish soldiers. By the end of the battle, an estimated 3,000 French were dead, compared to just a few hundred Flemish.

The gilded statue of the Groeninge Monument

The gilded statue of the Groeninge Monument© Kattoo Hillewaere

There were no crowds. No tour buses. Not even an information panel. I had hoped for something much more impressive, like the Civil War sites in the United States, or Waterloo in Belgium. After all, this was where Flemish identity was shaped. This was where they defeated the French knights wearing their fancy golden spurs.

Admittedly, it happened a long time ago. More than 700 years have passed, and almost nothing physical has survived from 1302. I already realised that a few years ago when I visited the Kortrijk 1302 Museum (now closed). Everything was a reproduction. The chain armour. The pikes. The illuminated manuscripts.

Nicaise De Keyser, Battle of the Golden Spurs, ca. 1836. The painting shows the climax of the battle: the assassination of Robert of Artois, commander of the French army

Nicaise De Keyser, Battle of the Golden Spurs, ca. 1836. The painting shows the climax of the battle: the assassination of Robert of Artois, commander of the French army© City of Kortrijk

There was just one tiny object in a glass case that might have come from the battlefield – a gold ornament from a horse’s bridle found in Sluis in the Netherlands. It was traced to Gwijde van Namen, a Flemish knight. Maybe it was a genuine relic of the battle. Maybe not.

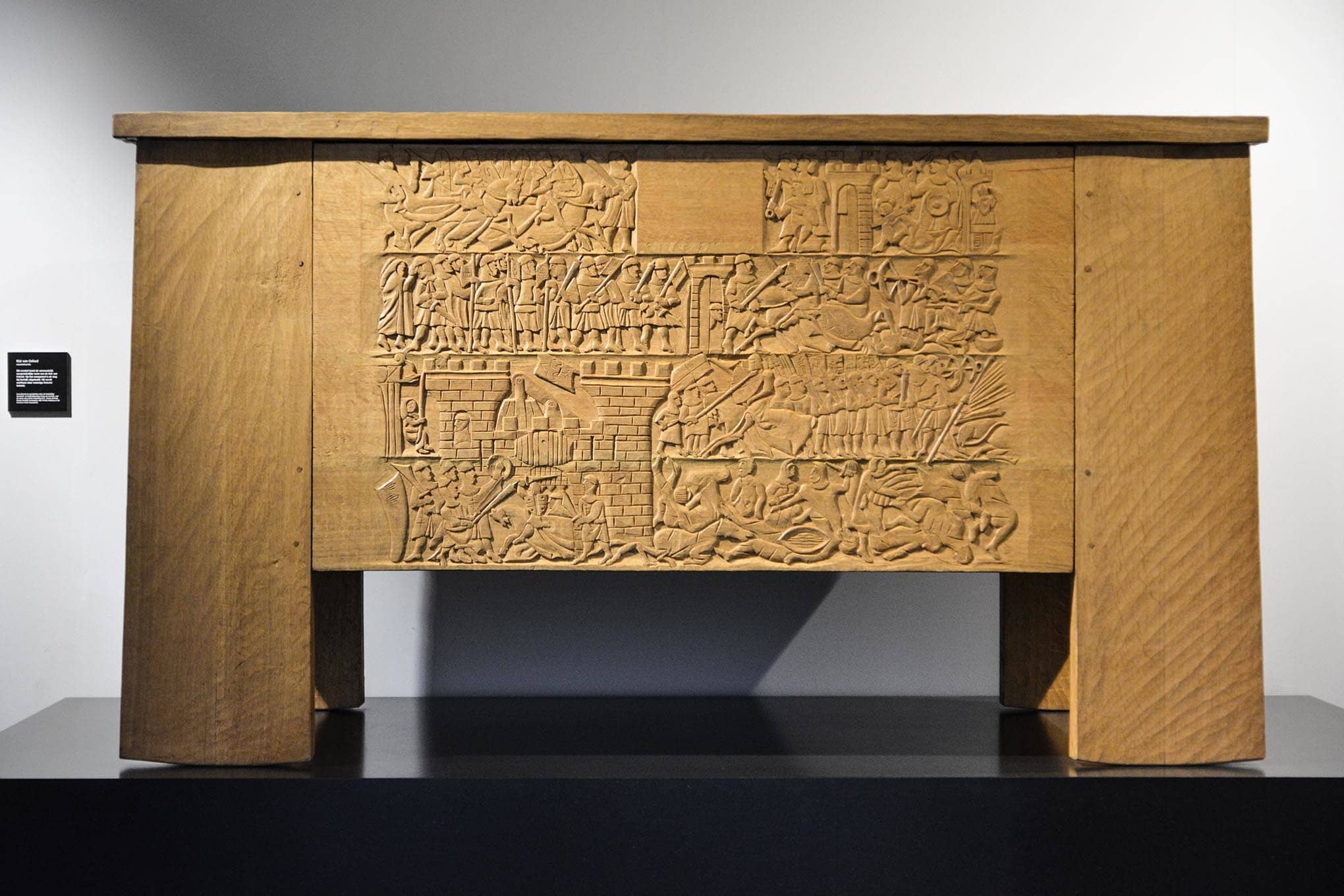

The main exhibit in the museum was a reproduction of the Oxford Chest, which is believed to be carved with scenes of the battle. The original (also known as the Courtrai Chest) was discovered in 1905 in a barn owned by New College in Oxford, and thought to date from 14th-century Flanders. But there are no plans to give the chest to Kortrijk, so they had to construct a replica.

Replica of the Oxford Chest, carved with scenes of the Battle of the Golden Spurs

Replica of the Oxford Chest, carved with scenes of the Battle of the Golden Spurs© Tourism Kortrijk

I was beginning to think that maybe the Battle of the Golden Spurs was not that important anymore. Maybe modern Kortrijk wants to be famous for something else. And so I headed back into the city to see what I could discover.

It isn’t that common to visit Kortrijk as a tourist. People go to Bruges, of course. You have to go to Bruges. They go to Antwerp, because it is fashionable, and Ghent, because it is cool, and Brussels, because it is Brussels. But Kortrijk is not on anyone’s list of 100 places to see before you die.

You soon see why. It is not the most beautiful city in Belgium. The station neighbourhood is a bit of a mess. Nothing much to see except a frituur, or fries shack, with a red neon sign that glows at night like a detail in an Edward Hopper painting.

The city doesn’t have an important art museum, or a famous restaurant or an annual festival to get excited about. So we can maybe give Kortrijk a miss, you might be thinking.

I would have said so when I visited in the early 1990s. I had been sent by a magazine to write about the town. ‘You won’t like it,’ a Flemish journalist warned me in advance. ‘We call it the Dallas of Flanders.’ He was right. I didn’t like Kortrijk. It seemed to lack the warmth of other Flemish cities.

The Saint Elisabeth beguinage in Kortrijk dates back to the year 1238.

The Saint Elisabeth beguinage in Kortrijk dates back to the year 1238.© Kattoo Hillewaere

But I did find a beautifully renovated beguinage behind an ancient church. A small gate led into a warren of cobbled lanes lined with old whitewashed houses once occupied by single women.

You find enclosed communities like this in many Flemish and Dutch cities. Hidden behind high walls, they offered protection, like towns within towns, for the single women who belonged to this relaxed religious order.

The last beguine passed away in Kortrijk in 2013. The modest beguinage houses have been restored to provide affordable local housing, while one tiny dwelling is preserved as a small museum. But you can find beguinages in Ghent and Bruges. You don’t need to go to Kortrijk if that is all it can offer. I came to that conclusion back in the 1990s.

But Kortrijk has changed over the past decade. In 2010, the city opened a €200 million downtown shopping centre called K in Kortrijk. It was a big success for a few years, bringing more life to the streets, but now internet shopping is killing off the shopping mall. Several stores now lie empty, with no sign of an upturn on the way.

Shopping centre K

Shopping centre K© Kattoo Hilllewaere

The streets around K are a confusing mix of small shops, car parks and modern buildings. You come across the occasional old building, like the small whitewashed almshouses of the Baggaertshof. Reached down a narrow passage, this complex of 13 dwellings was built in 1638 for ‘unmarried women of unblemished character’.

The beautiful overgrown garden is planted with mediaeval medicinal herbs and a lovely mulberry tree. It could almost be in Bruges, except it is surrounded by that unsettling Kortrijk mix of architectural styles, from ancient stone churches to concrete office blocks, with odd gap sites in between. Something wasn’t right about Kortrijk, I began to realise. It didn’t have the harmony of other Flemish cities. And I eventually found out why.

The Baggaertshof is a hidden gem in the Kortrijk city centre.

The Baggaertshof is a hidden gem in the Kortrijk city centre.© Tourism Kortrijk

Kortrijk 1944

War.

Forget 1302. The big battle was in 1944. The old town is dotted with information panels that illustrate the destruction of Kortrijk at the end of the Second World War. The town was the target of an Allied bombing campaign aimed at knocking out the railway junction. But a lot of the bombs hit innocent targets, destroying hundreds of houses, a cinema, a hotel, the main post office and the mediaeval cloth hall. Most of the town’s art collection was lost, including a famous 19th-century painting of the Battle of the Golden Spurs. More than 500 people died in a relentless campaign that left much of the city in ruins.

The town marked the 75th anniversary of the air raids by putting up signs near the spots where the bombs had fallen, along with a brief description in three languages and a photograph from the archives.

In 1944, Kortrijk was several times the target of an Allied bombing campaign.

In 1944, Kortrijk was several times the target of an Allied bombing campaign.© Beeldbank Kortrijk

The town was finally liberated on 4 September when a jeep full of British soldiers drove into the Grote Markt. The local council decided not to rebuild the old houses, the way they did in Ypres and Leuven after the First World War. Instead, they tore down the ruins and put up 1960s office blocks and apartment buildings, or they just left the wasteland as a car park.

It is a miracle that anything old has survived, given the city’s calamitous history

It is a miracle that anything old has survived, given the city’s calamitous history. When you search online for “the Battle of Kortrijk”, you are directed to Wikipedia, where you discover the search term may refer to the battle of 1302, or a battle of 1580 during the Eighty Years’ War, or a battle in 1793 between the French revolutionary army and an Austrian-British army, or a battle one year later again involving the French, or a battle in 1814 between Napoleon and troops from Saxony, or (bear with me) a battle of 1815 during Napoleon’s final campaign or a battle of 1918 at the end of the First World War.

The Chapel of the Counts in the Church of Our Lady

The Chapel of the Counts in the Church of Our Lady© Kattoo Hillewaere

It would hardly be surprising if nothing was left. But then you sometimes stumble upon a rare building from the Middle Ages, such as the ancient hospital chapel on Buda island, reached down a dusty corridor lined with worn flagstones, or the Church of Our Lady, where the golden spurs torn from dead French knights were once hung from the roof (they are now replaced by replicas). This church also contains a lovely chapel with 102 Gothic niches decorated with portraits of Flemish counts and a horrific sculpture representing death that should come with a warning.

The church and chapel will provide the setting for a new exhibition of objects brought from the Kortrijk 1302 Museum. It is due to open on the 720th anniversary of the battle, 11 July 2022.

You come across other ancient buildings that survived the bombing, including the handsome Hotel Damier on the main square, whose 1769 façade is still intact. And you can eat in the restaurant De Trog, where lunch is served in an elegant 19th-century town house that once belonged to a Kortrijk brewing family.

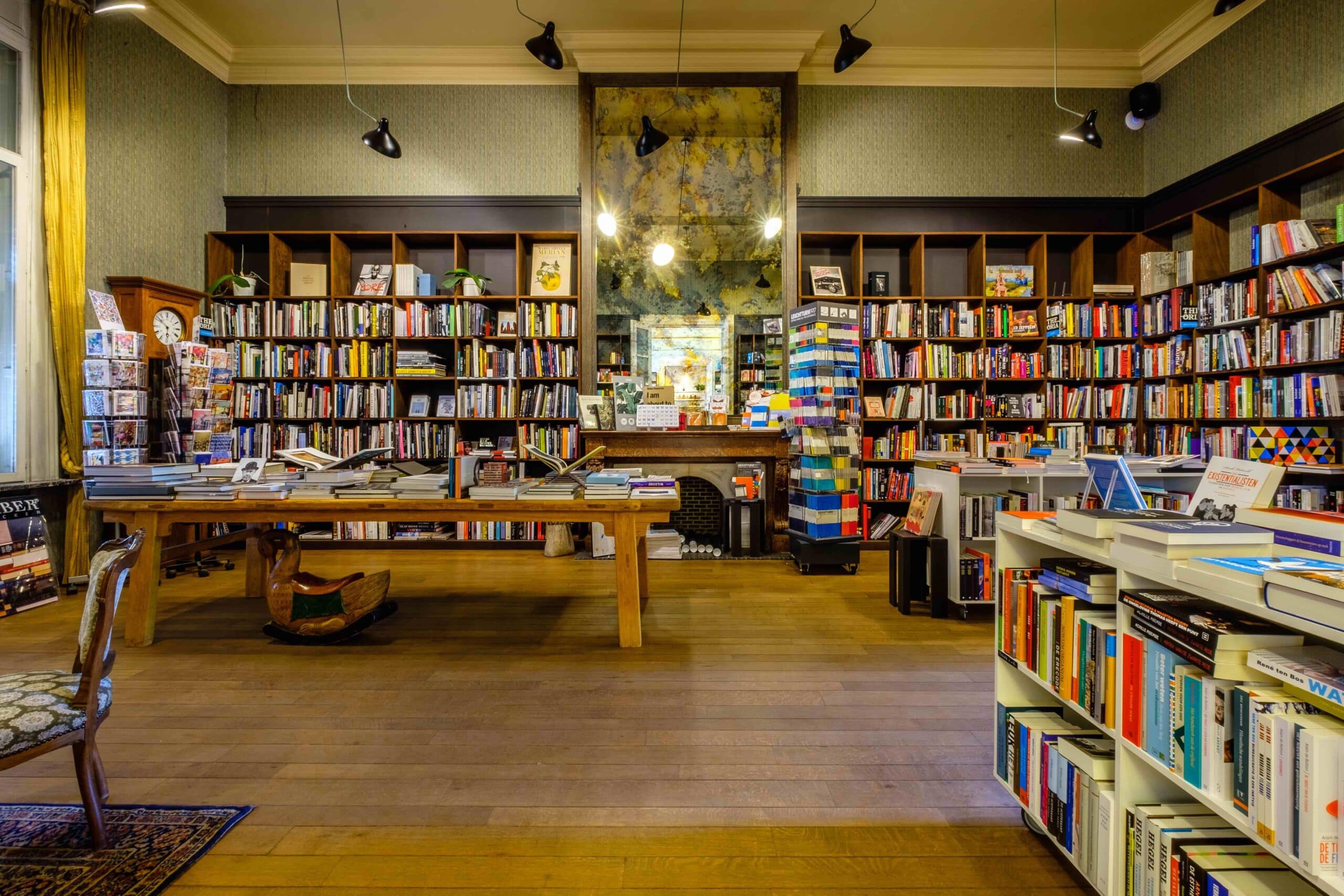

Bookshop Theoria

Bookshop Theoria© Kattoo Hillewaere

One of the finest buildings to survive stands in the badly-damaged station neighbourhood. Lovingly restored in 2017, the former Neoclassical casino is now home to a spectacular bookshop with a grand entrance hall, polished parquet floors and a sweeping marble staircase. The owners of Theoria have added literary details, including life-size figures from Tintin comics and portrait photographs of visiting writers. And there are armchairs and little tables scattered around where you can sit with an espresso coffee or a local beer.

The Broeltorens

The Broeltorens© Kattoo Hillewaere

The Golden River

It took me a while to reach the river Lys. I hadn’t found it interesting when I visited in the 1990s, apart from two ancient round towers on opposite quays known as the Broeltorens. But the historic waterfront has changed dramatically in recent years. Once nothing more than a large car park, it is now lined with landscaped quays and even an urban beach where locals sit out on sunny days with bright umbrellas and beers.

The river Lys with the winding College bridge

The river Lys with the winding College bridge© Kattoo Hillewaere

The city has added to the visual impact by building a series of seven new bridges over the river. The most striking is the shiny steel College bridge designed by architects Sum Projects to carry cyclists and walkers over the river in a series of sensual curves. On the riverbank nearby, the Kortrijk artist Ann Demain placed a massive bronze nude known as Mother Earth II, half-buried in the ground.

A waterfront walkway leads to the relocated Texture museum. Now based in a vast former warehouse, the museum is dedicated to the local flax industry. Boring, you might be thinking, but you’d be wrong. The museum brings the story of flax to life with a creative mix of touch screens, video interviews, historic photographs, microscopes, scanners and fabrics you can touch.

Texture Museum

Texture Museum© Kattoo Hillewaere

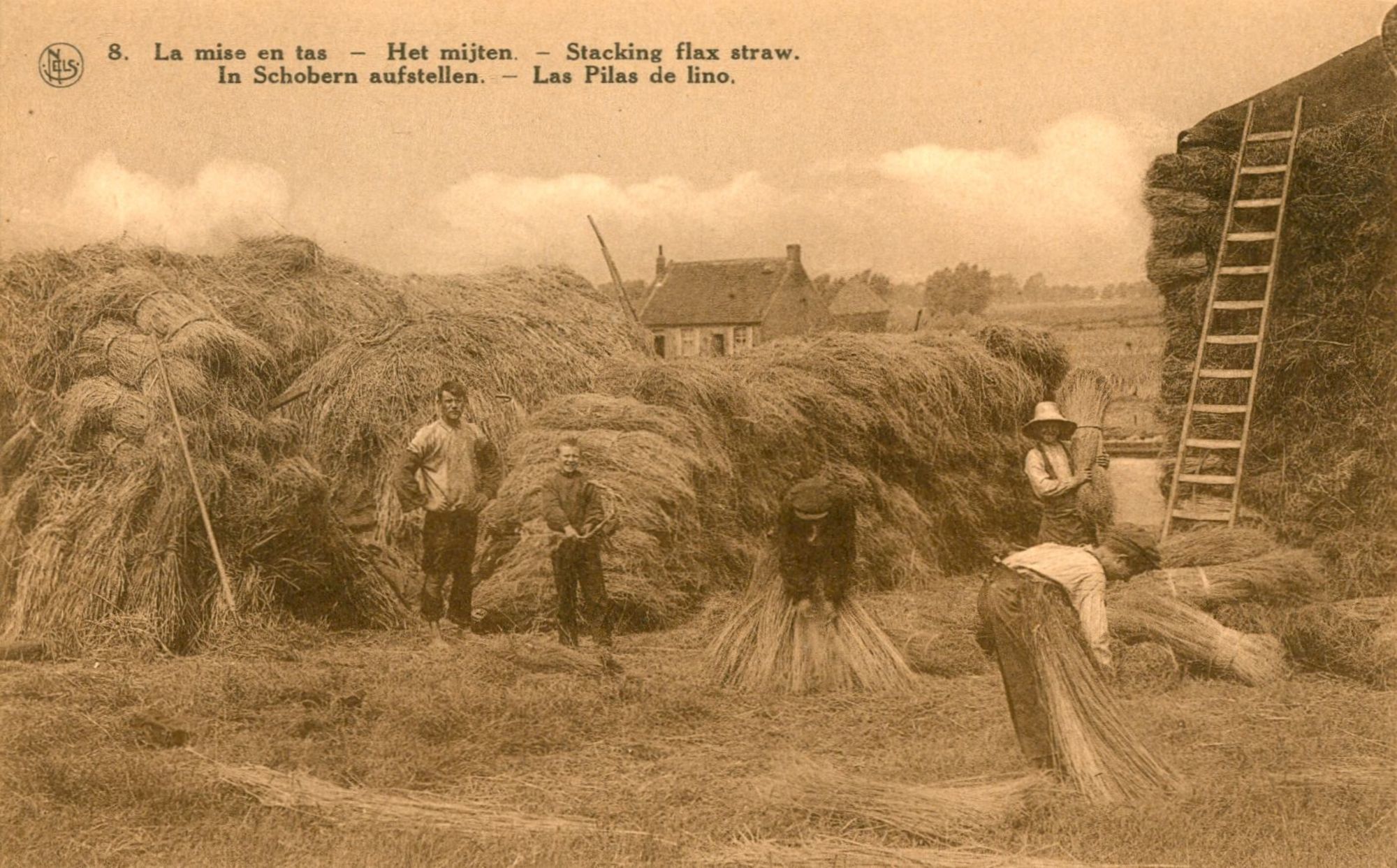

It soon becomes clear that Kortrijk owes its wealth to flax. This exceptional crop flourishes in the damp, mild climate along the river Lys, flowering just one day a year. Cultivated since the Middle Ages, it provides the raw material for linen fabric, as well as ropes, tents, mailbags and construction material. And the linseed oil from flax was used by Van Eyck to develop oil painting, the museum explains.

‘I am a big fan of linen,’ says Bruno Van Gils of men’s tailors Café Costume in one of the museum’s touch-screen video interviews. He explains that a linen suit is a unique creation with a quality of ‘disciplined nonchalance’.

Even more surprising is the video report that shows the owner of a flax warehouse near Kortrijk holding up a U.S. dollar bill. ‘The banknote comprises 75 per cent cotton and 25 per cent flax from Kuurne,’ he explains. ‘The texture is different from euro notes, which don’t contain any flax.’

Stacking flax along the river Lys

Stacking flax along the river Lys© Stichting de Bethune Marke

The flax growers were originally local farmers who cultivated the crop in their fields. They became fabulously rich from this commodity, known as Courtrai flax, which produced the finest quality linen. The river Lys eventually became known as “the Golden River”.

‘Flanders has nothing to fear,’ declared Charles V, ‘as long as flax grows in its fields and there are fingers to spin and hands to weave. The Flemish will always be rich as long as they don’t chop off the thumbs of their spinners.’

For several centuries, the wealth from flax shaped the identity of Kortrijk

For several centuries, the wealth from flax shaped the identity of Kortrijk. It led to a community of English merchants settling in the town to buy up flax for British factories. In 1939, a luxurious Art Deco apartment building known as The White Residence was constructed by the flax merchants A. and C. De Witte. As recently as the 1950s, a 5,400-kilo consignment of flax was enough to buy a plot of land in West Flanders and build a family home.

Inside Texture

Inside Texture© Kattoo Hillewaere

As I wandered through the old warehouse, it struck me that this was where you should come to understand Flemish identity. The flax fields have shaped this region of Europe far more than the battle fought in 1302. This miraculous crop led to Van Eyck’s portraits, linen suits, nonchalant fashion, and those dollar bills that are one-quarter Flemish.

But it’s all over now. The huge flax warehouse once owned by the Linen Thread Company is now occupied by Texture. The flax trade has moved somewhere else and Kortrijk will have to reinvent itself somehow. With that thought in my head, I walked back to the station quarter.

Kortrijk 2030

I had already noticed something interesting was happening in the war-damaged district next to the railway yards. There is a new Kortrijk emerging here that has nothing to do with golden spurs hanging from church beams or flax grown along the banks of the Lys.

Concert venue De Kreun

Concert venue De Kreun© Kattoo Hillewaere

In recent years, the city has reinvented itself as a music hub. The 1960s Muziekcentrum was recently transformed into a smart new venue named Track with six concert halls, a ballet studio, rehearsal rooms, classrooms, a recording studio, radio station and a bustling café. It stands next to De Kreun complex which was renovated in 2009 as a venue for rock and pop concerts.

Several bands have been formed in Kortrijk, including Goose, Balthazar and SX. I’m not sure if you can talk about a Kortrijk sound, but maybe SX shaped it in their early years, when singer Stefanie Callebaut’s mysterious, alien voice dominated tracks such as Black Video.

Away from the concert venues, the new relaxed Kortrijk mood can be experienced in several cafes and restaurants. You feel it when you enter the restaurant De 7 Zonden at Leiestraat 22. Hidden inside an old government building, it’s a relaxed place with raw wood tables, old beer crates turned into bookcases and potted ferns. The inexpensive daily menu starts with a big tureen of homemade soup and a hunk of thick brown bread, just like your grandmother used to make.

At the end of the day, students and locals settle into bars on intimate squares or along the waterfront. You might take a look inside deDingen at Budastraat 12 where the interior is decorated with a casual mix of assorted chairs, vintage lamps and vinyl records. They recently added a crowdfunded microbrewery in the back where they bottled their first Ruimtegist beers in early 2020.

The new Kortrijk Weide neighbourhood where abandoned railway sheds have been renovated to create a new urban hub.

The new Kortrijk Weide neighbourhood where abandoned railway sheds have been renovated to create a new urban hub.© Gerald Van Rafelghem

Now a member of Unesco’s Creative Cities Network, Kortrijk shows off its innovative spirit in a walking route that takes in six vibrant districts. I had already discovered some of the city’s creative hotspots, but the walk introduced me to the new Kortrijk Weide neighbourhood where abandoned railway sheds have been renovated to create a new urban hub. The project includes a city park, tropical swimming pool, events hall, youth centre and digital industries site.

The city is now hoping to win the nomination for European Capital of Culture in 2030. It could happen. Kortrijk has come a long way since 1302.

This article was realised with the support of the Flemish Government.