Latin Was the Only Truly European Language

In the series Babel in the Low Countries, editor-in-chief Luc Devoldere contemplates the way we use language today, but just as easily delves into the past to consult with historical figures and writers who stand guard over language. In this article he examines the essential role Latin has played in the religious and scholarly history of the Low Countries.

Let us turn a final time to a language that lingered on in the Low Countries for at least two millenniums. Not in spoken form, but as the chosen language of scholars and religion. Latin. If there ever was one language we could label eminently “European” – within the Low Countries as well –, it must have been Latin. It was the language of the Roman Empire, Catholicism and scholarship until about 1700.

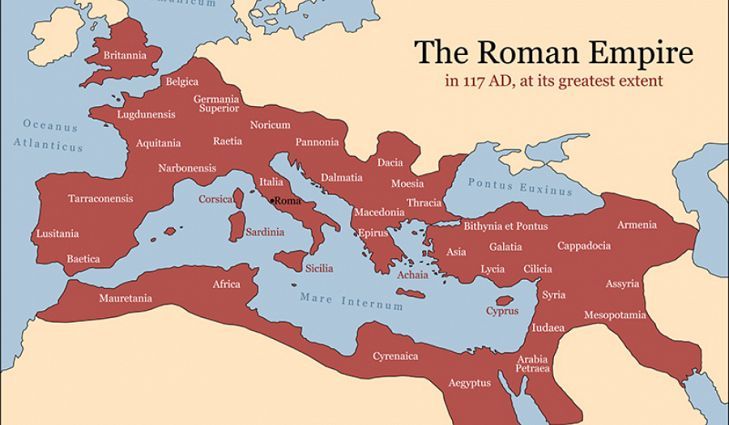

Apart from being many Europeans’ mother tongue, it became their ‘paternal tongue’ for many centuries. The Roman Empire is still part and parcel of our collective memory as being one of the most successful attempts at organising and governing a large part of the world. Christianity first adopted Greek – or koinè dialektos, to be exact, or ‘the common language’ – in spoken form, the lingua franca of the eastern Mediterranean. At the moment Peter was crucified in Rome, it was established Latin would someday become the language of the Church. The Roman Empire fell, whereas the Church hung on to the language of Rome.

The Roman Empire at its greatest extent

The Roman Empire at its greatest extentAround 1300, Dante wrote his Divine Comedy in the Tuscan dialect, his mother tongue (vulgaris eloquentia), but he still had to defend using it in a literary context in an essay, written in scholarly Latin. Petrarch rang in humanism, the intellectual movement that would liberate itself from the clergy’s monopoly on knowledge and language. The humanists purged Latin of its scholastic darkness. They wanted to return to the classical Latin sources, and sought to write and think more clearly. Lorenzo Valla and Erasmus would perfect what Petrarch had started.

Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374), founder of humanism

Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374), founder of humanismNevertheless, Erasmus, of Brabantine descent, who had started to speak, write and think in Latin – as fluent as the Italians did – decided to go back to his mother tongue on his Basel deathbed. Allegedly, the humanist’s dying words were “Liewer Gott”, according to German humanist Beatus Rhenanus’ transcripts.

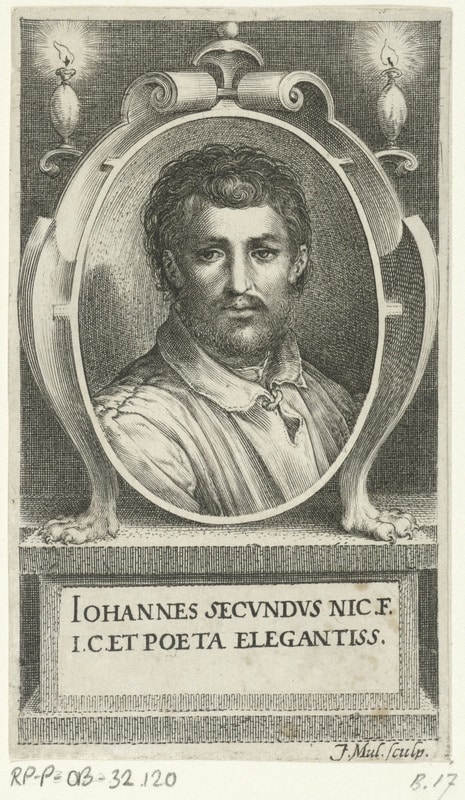

Janus Secundus, i.e. Jan Everaerts, who was born in The Hague in 1511 and died before his twenty-fifth birthday, is the best-known Dutch poet… in Latin. He was a brilliant Latinist, as was Erasmus. His Basia, or kiss poems, have been translated numerous times into various languages, and were being read all over Europe. Scientist Simon Stevin, who had left the South for the North, and was not fluent in Latin at all, passionately embraced the Dutch language, which he referred to as the Duytsche Tael, as the language of science. It is to him we owe words such as ‘driehoek’ (triangle), ‘vierkant’ (square) and ‘wiskunde’ (mathematics), as well as ‘raaklijn’ (tangent) and ‘gezichtseinder’ (horizon).

Dutch poet Janus Secundus (1511-1536) wrote in Latin

Dutch poet Janus Secundus (1511-1536) wrote in LatinLatin remained the language of the intelligentsia until about 1700. Two final works of importance written in Latin are Spinoza’s Ethics and the Principia mathematica philosophiae naturalis by Newton. Cartesius – i.e. Descartes – was already unsure whether to choose Latin or French. His French-language books wee translated into Latin, and his Latin works into French. Descartes claimed to have written his Discours de la méthode in French “à cause que j’espère que ceux qui ne se servent que de leur raison naturelle toute pure jugeront mieux de mes opinions que ceux qui ne croient qu’aux livres anciens.” (“because I hope that those who just rely on their pure, natural reasoning will hold my opinions in higher regard than those who solely believe in old books.”) Apparently, the innovative potential of Latin had worn off: in the continuous “querelle des anciens et des modernes” (“quarrelling between the elder and the modern”) the elder seemed destined to lose out.

In her novella entitled Un homme obscur, Marguerite Yourcenar had her protagonist, the virtually illiterate Dutchman Nathanaël, address a young, French Jesuit, who is on death’s door on an island off the American coast, in Latin. This scene is set in the 17th century. Nathanaël does not speak a word of French, whereas he does speak English, and managed to pick up a little Latin along the way. The Jesuit does not know any English or Dutch. Hence Nathanaël’s choice. Latin is the bridge allowing those two men to forge a connection on that remote island on the other side of the world, miles away from Europe.

This story gets to me somehow. Nonetheless, French took the cake around 1700, and took over from Latin. French became the preferred language of every single European court (which all modelled themselves on Versailles), as well as the language of diplomacy, and the European salons. In the 18th century, it served as one of the most important vehicle for Enlightenment.

Latin is often denounced for being elitist, but not a single European nation could feel disadvantaged by it

This is where Latin’s story ends. It had lost its momentum. It remained the official language of Ghent University, founded by William I, up until 1830. Nowadays, Latin is increasingly considered a kind of Sanskrit, a language that can only be understood by a limited number of experts. Latin is often denounced for being elitist, but people tend to forget that, before, anyone had to master it as a second language. Therefore, there was a level playing field, and not a single European nation could feel disadvantaged by Latin. Those days, however, are gone.

Esperanto will never be able to follow into those footsteps, no matter how idealistic its supporters are. An artificial language can never conquer the world. At the start of the 20th

century, people in the tiny independent condominium of Neutral Moresnet, lodged in between Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany, attempted to make Esperanto the region’s official language. A national anthem, however, was as far as their efforts took them. Today, Europe’s lingua franca – and, to be fair, that of the pretty much the entire world – is English. That is to say, the kind of English non-native speakers tend to speak and write.