Laurens Legiers Distils the Essence From Dream Images

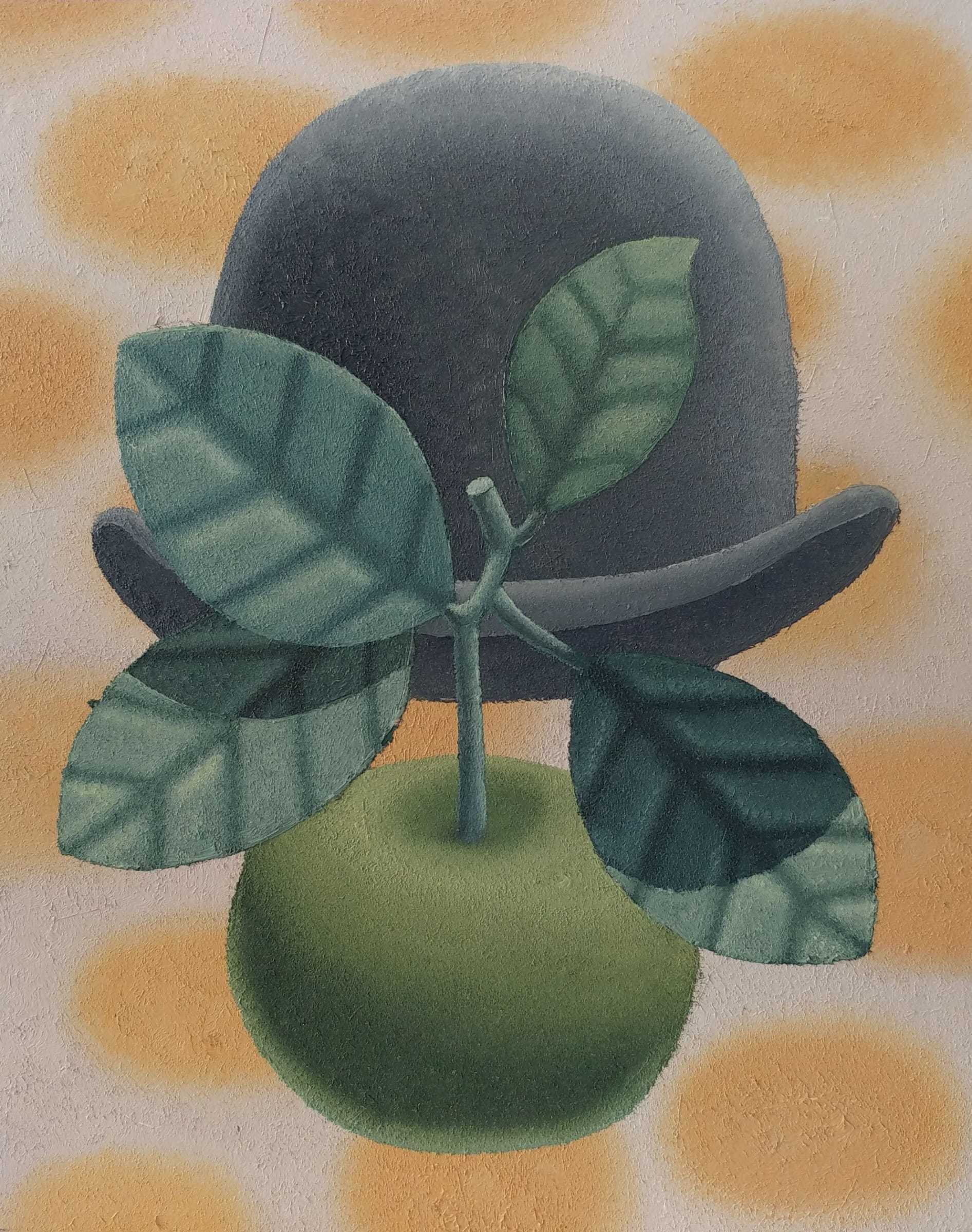

Antwerp painter Laurens Legiers (b. 1994) takes animals, plants, and sailing boats, and formalises them, creating motifs that repeat through his paintings. Heavily stylised, with a strong sense of symmetry, they could be dream images, or cards dealt from a surreal tarot.

Legiers’ paintings are immediately recognisable, and have quickly attracted international attention. After a first solo show at the Plus-One Gallery in Antwerp in 2020, his work travelled the world in 2021, appearing in group shows in New York, Los Angeles, Hong Kong and London. This month sees his first international solo show, at Gallery Vacancy in Shanghai.

Laurens Legiers

Laurens LegiersBut his distinctive style was not apparent when he graduated in 2018 from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, his home town. At this point, his paintings were inspired by Greek and Roman culture and myth. They feature vertiginous, brightly coloured landscapes scattered with broken columns, arches, and cypress trees. Characters from the myths are represented by prominent symbols: a half-shell rising from foam for Venus (via Botticelli), untended fires for Prometheus.

Geboorte van Venus (Birth of Venus), 2018

Geboorte van Venus (Birth of Venus), 2018© PLUS-ONE Gallery

While these paintings are already rather stylised, they still appear rooted in an attempt to capture real landscapes, which Legiers had seen and photographed in Italy and Greece. The colours make the strongest impression — the sun-drenched wheat, the moonlit water — rather than the totemic objects scattered around the landscape. Colour is also foremost in other paintings, featuring rainbows, sunflowers and daffodils.

A Statue for Guston / A Statue for Van Gogh, 2019

A Statue for Guston / A Statue for Van Gogh, 2019© PLUS-ONE Gallery

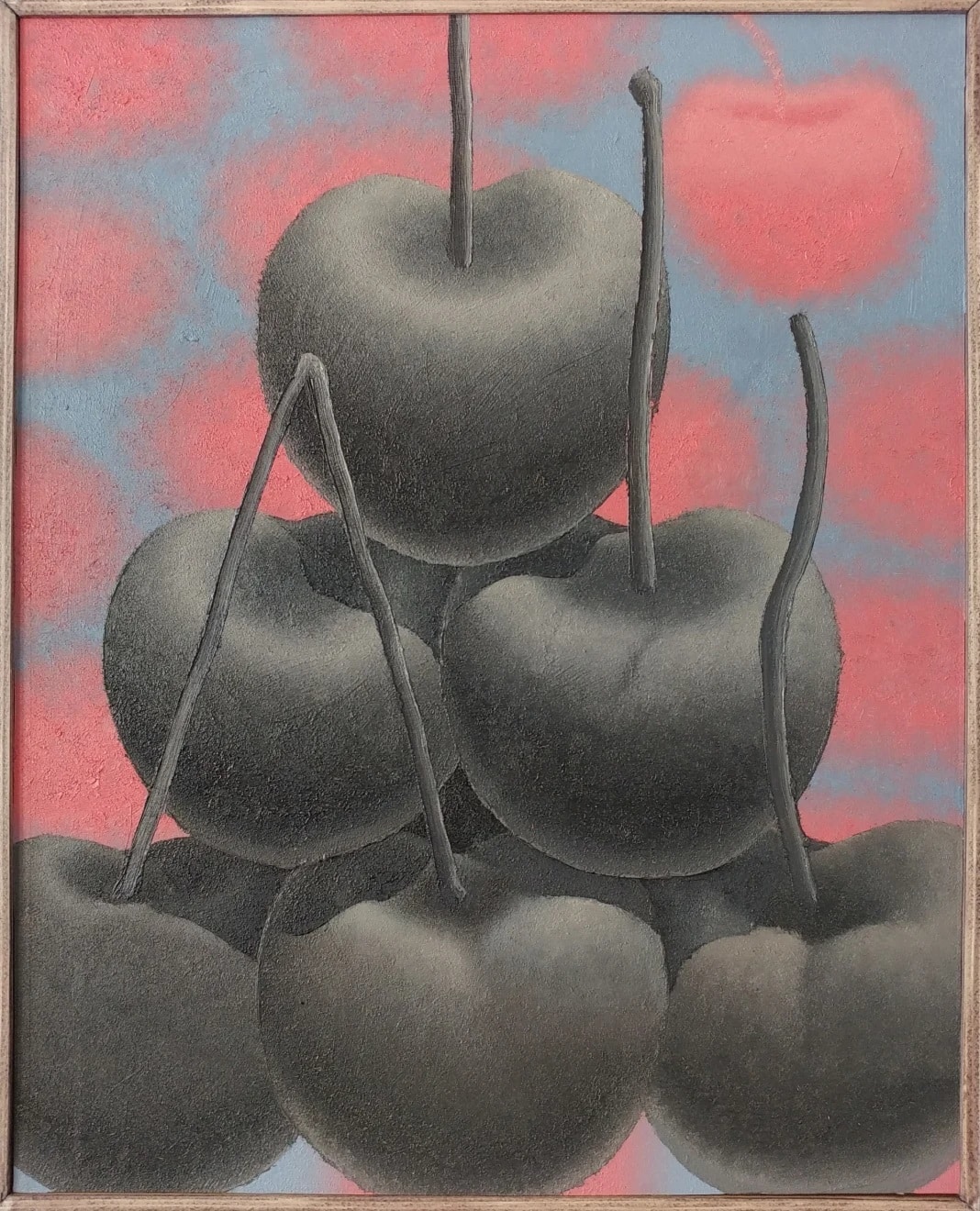

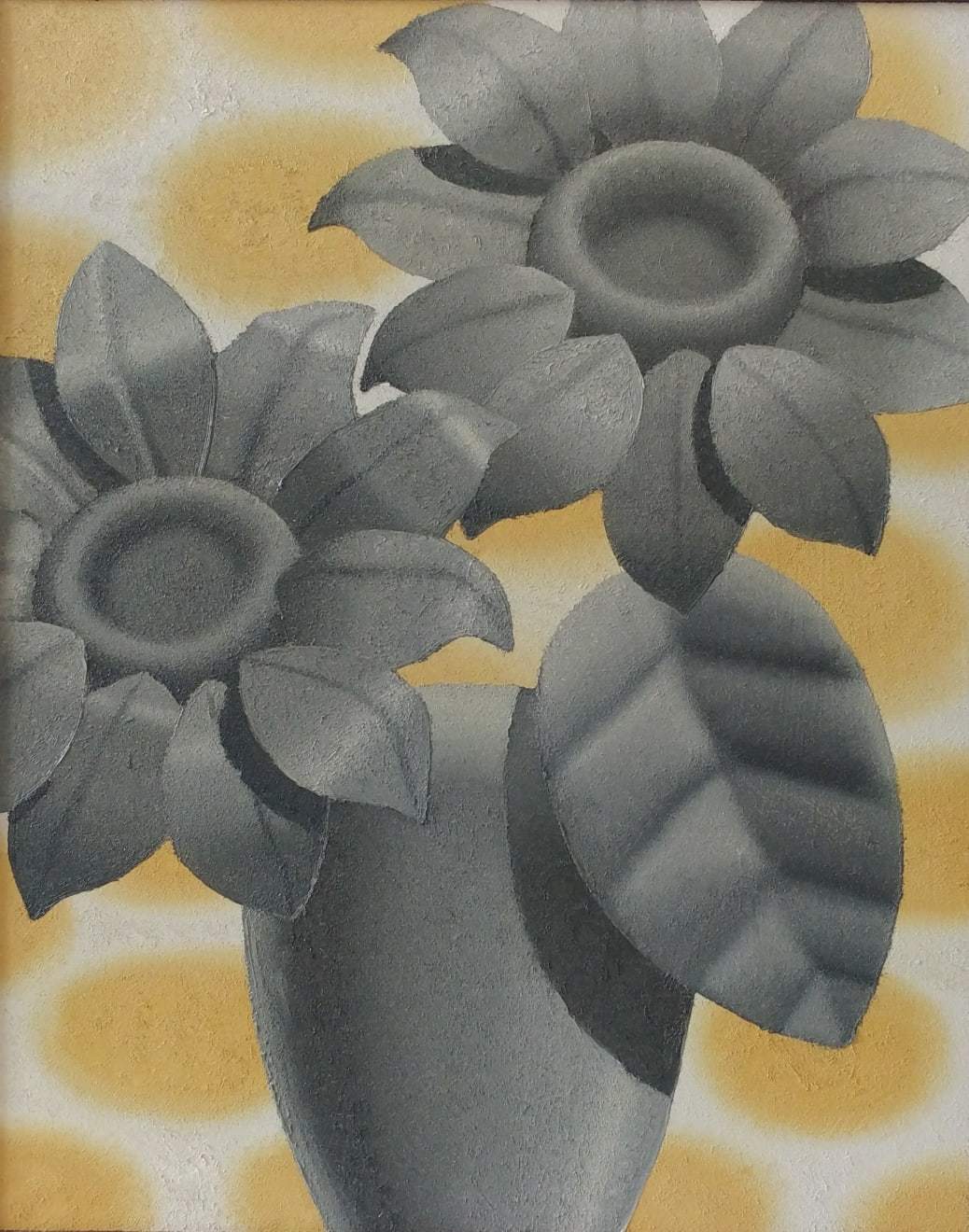

But a change was coming. The work Legiers produced next focused on objects rather than landscapes, and used muted tones rather than bright colours. A series of ‘statue’ paintings produced in 2019 feature grey objects that practically fill the frame, with just a glimpse of pastel forms behind. They appear to be in a dream space that recalls the work of surrealists such as René Magritte. Several of these paintings are addressed to other artists: A Statue for Van Gogh

has grey sunflowers in a vase backed by smudges of yellow. A Statue for Guston has grey cherries in the foreground, with a wallpaper of pink cherries behind.

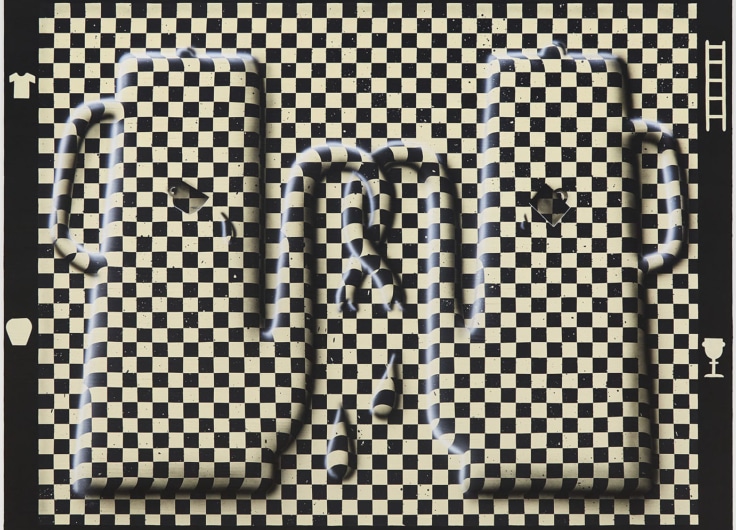

Ode aan Magritte, 2019

Ode aan Magritte, 2019© PLUS-ONE Gallery

These are thematic tributes rather than expressions of a debt of style. Nothing could be further from Van Gogh’s fiery flowers or Philip Guston’s cartoonish Cherries. But Ode aan Magritte (Tribute to Magritte) is closer to home, combining a bowler hat, an apple, and the kind of stylised leaves that recur in Magritte’s paintings. A further surrealist echo, this time with Dali, comes through with Legiers’ obsession with snails, which sometimes appear as background, sometimes as the main subject.

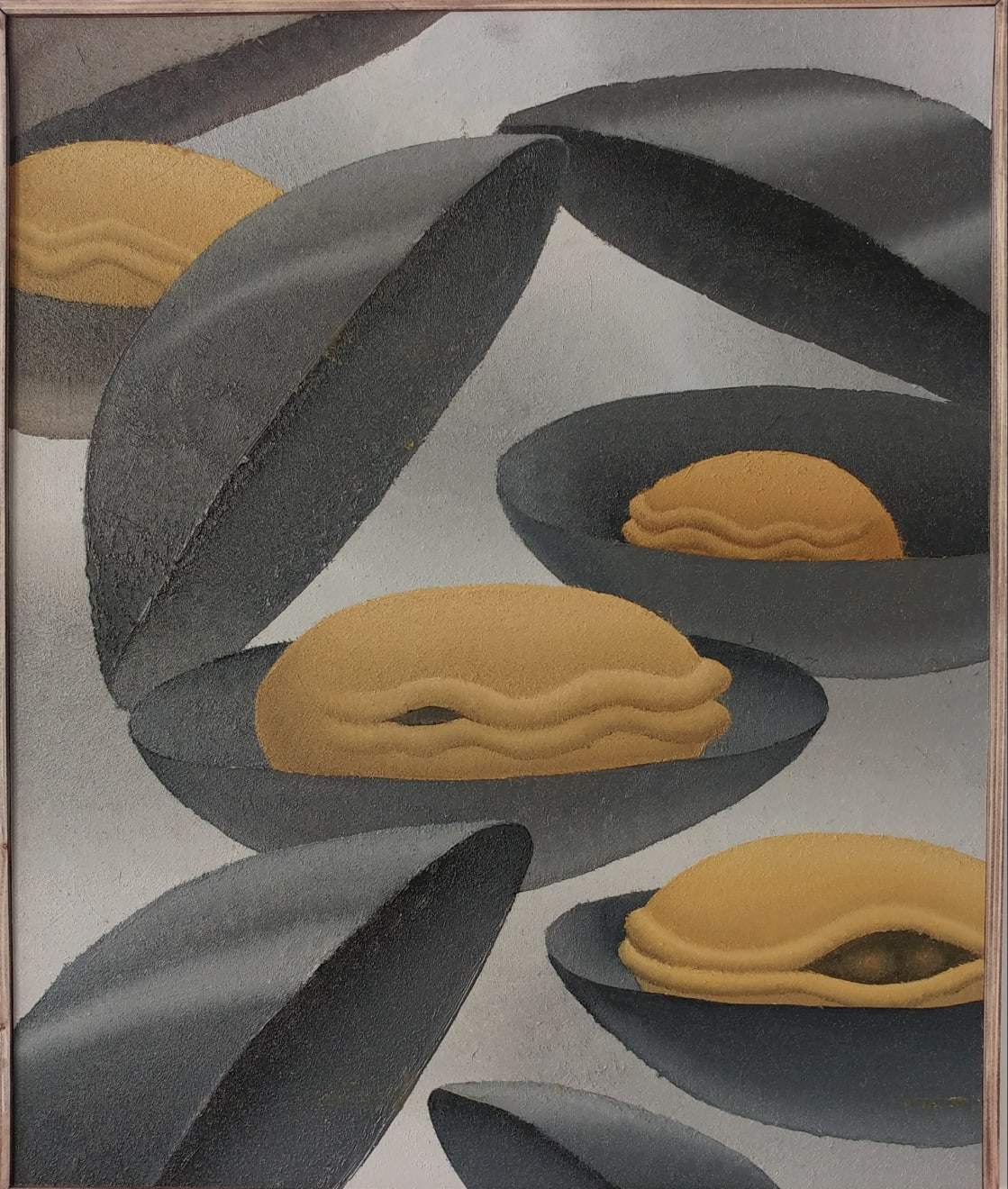

Belgium Mussels, 2019

Belgium Mussels, 2019© PLUS-ONE Gallery

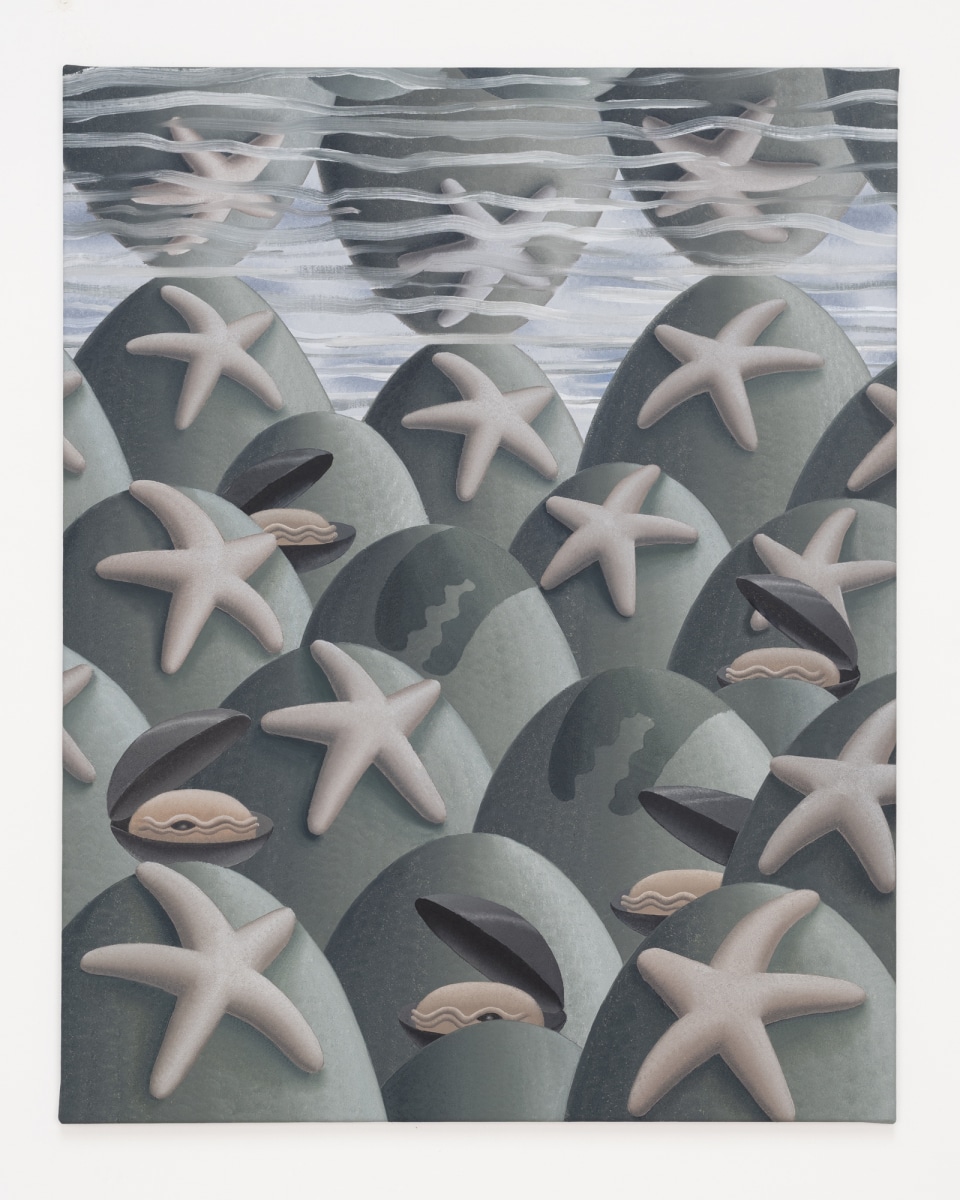

The style that Legiers developed in these paintings shares Magritte’s interest in ideal forms: the apple that stands for all apples, the man in a bowler hat who stands for humanity, the leaf that stands for the whole tree. Looking for a Belgian theme, Legiers chose – rather predictably – the mussel, which he paints fleshy and thick-lipped, sitting on a too-perfectly smooth shell. The detail, even the natural texture, is stripped away, reducing the mussel to an ideal form. A similar treatment makes motifs of lobsters, starfish and shrimp.

But the way Legiers deploys these motifs is what drives his style. Each painting deploys several of his forms in a tightly controlled arrangement that feels claustrophobic, even in the larger canvases. This sensation is heightened by a strong sense of symmetry, with the forms sometimes arranged in diagonals or as mirror images. This is most pronounced in his scenes with sailing boats, which face each other on rippling water, or sink into their own reflections.

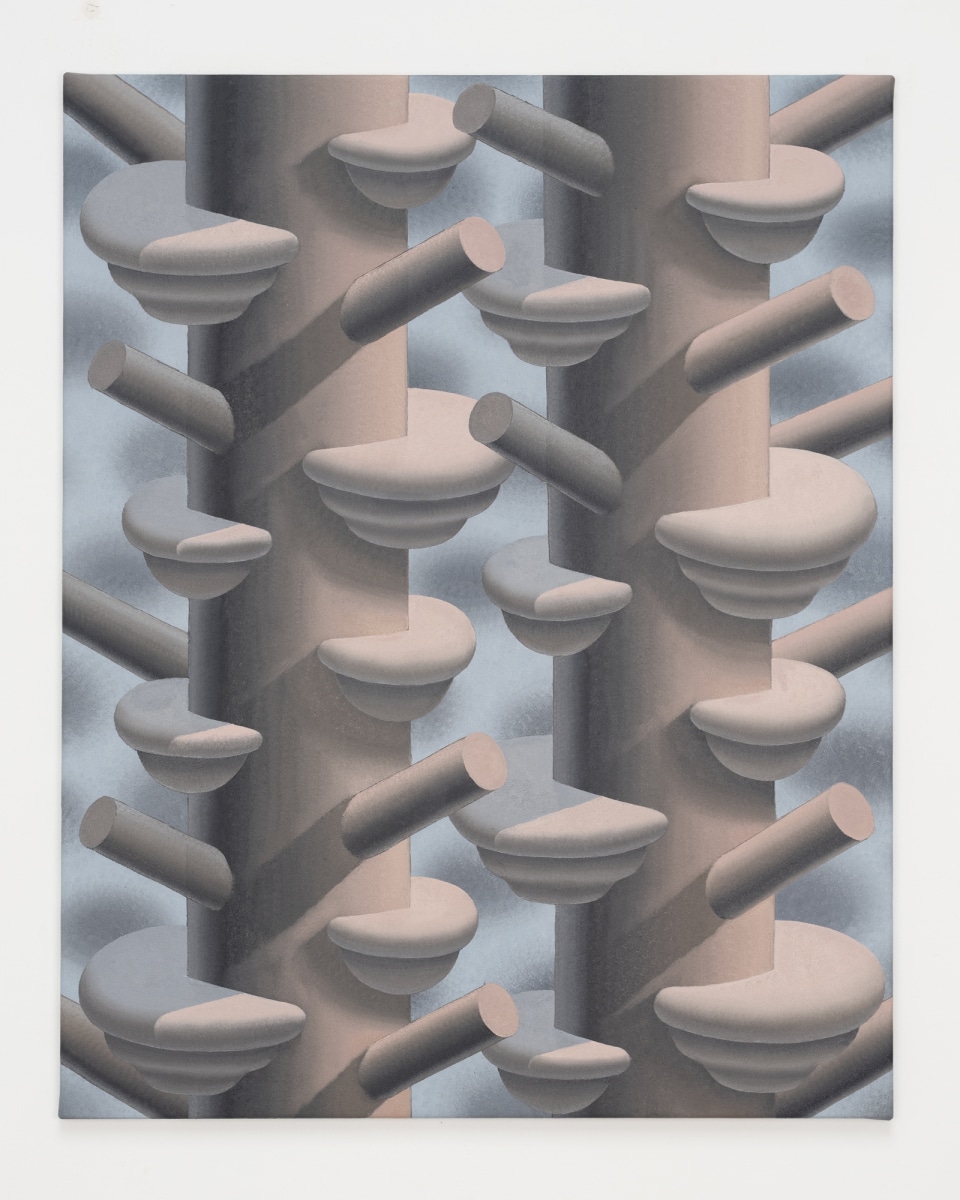

Elfenbankjes, 2020

Elfenbankjes, 2020© PLUS-ONE Gallery

Yet even when there is no precise geometry, there is a feeling that the arrangement of forms follows some underlying framework or set of rules. This brings to mind the illusionistic drawings of MC Escher, although Legiers stops short of the game playing to be found in Escher’s infinite staircases or birds transforming into fish. Yet there is a similar sense of unnatural structure in the way Legiers arranges bracket fungus up tree trunks in Elfenbankjes, or piles up branches to imprison lobsters.

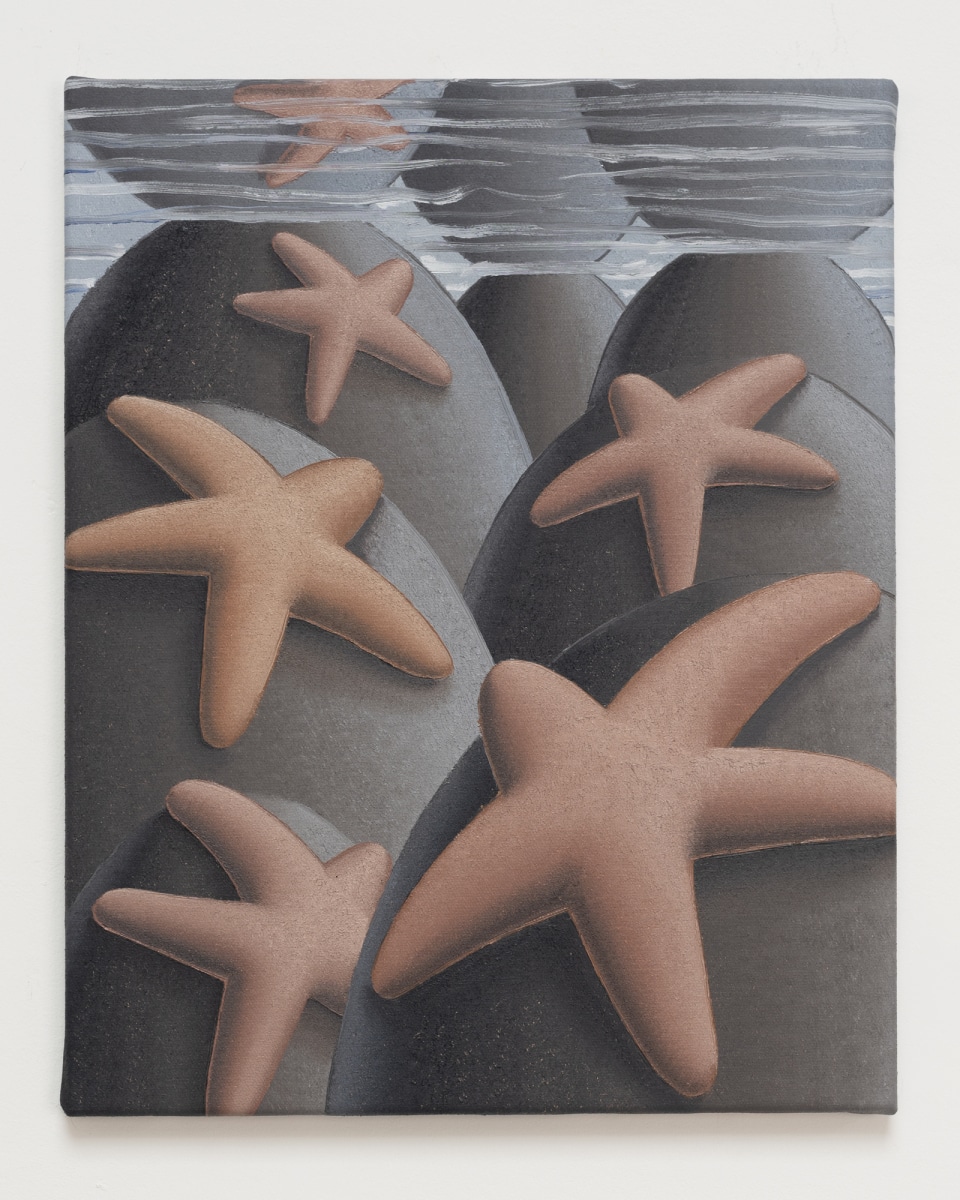

His scenes take place in a flat, surreal space where there are contours but no real depth. Yet there is light and shade in his paintings, which pulls you back to a kind of reality. The greatest sense of depth is felt underwater: there is a slight hint of the water’s surface at the top of paintings such as Resting Sea Stars and Threatening, the latter only giving up its meaning when you notice the fragmented shadow of lobster claws cast on the stones. A similar subtle game with shadow and light takes place in Ship in the Evening Light, where the meaning of the pastel band at the top of the sail suddenly becomes clear: the sun is setting behind the mountains.

Resting Sea Stars / Threatening / Ship in Evening Light, 2020

Resting Sea Stars / Threatening / Ship in Evening Light, 2020© PLUS-ONE Gallery

Seen together, there is also an ambiguous sense of scale in Legiers’ paintings. The rocks beneath the water and the distant hills have the same ovoid form, so you start to wonder if you are looking at a real sailing boat, or toys in a pond. And some of the ovoids could simply be eggs. Perhaps these are all still lives rather than landscapes after all.

Struggling in Bad Weather, 2020

Struggling in Bad Weather, 2020© PLUS-ONE Gallery

In Legiers’ subsequent work, the combination of forms becomes more complex and the layers multiply. Raindrops now cascade across the face of his paintings, as in Struggling in Bad Weather, the drops forming a curtain in front of snails scaling fallen branches. His raindrops are no less stylised than the rest of his forms, yet here (and in the ripples on water) there is a chance to see the thickness in the paint and a hint of the artist’s hand.

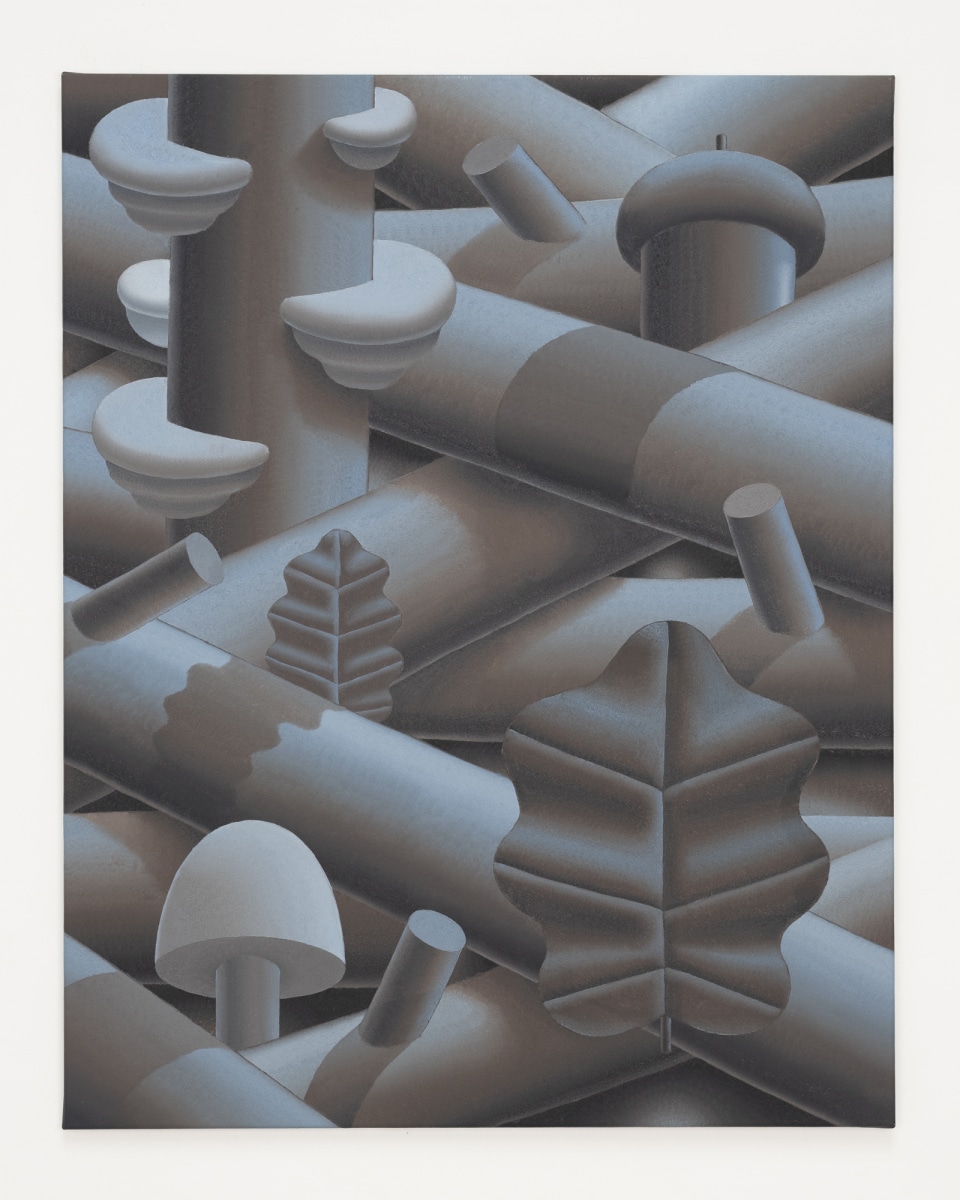

A Memorable Walk, 2020

A Memorable Walk, 2020© PLUS-ONE Gallery

A Memorable Walk crams together branches, bracket fungus, oak leaves, a toadstool and an acorn, creating a sense-impression of a walk, but showing nothing of the path taken or the land crossed. The crepuscular light suggests evening has overtaken the walker, or that the impressions gathered have all been put away in a dark cupboard. Just as Legiers now paints from memory rather than from photographs, so his pictures start to feel like paintings of memories rather than of the remembered objects. He is showing us a space where our visual perceptions are stored, reduced to their essence, and perhaps already touched by the first effects of forgetting.

His latest show, at Gallery Vacancy in Shanghai, contains new work that expands on past obsessions. The crepuscular forest continues to fascinate him, with fallen leaves now draped limply over the fallen branches, in a way that is at once natural and suggestive of Dali’s melting clocks. Legiers’ world feels so rigid that any softness comes as a surprise.

Rising Black Lobster, 2021

Rising Black Lobster, 2021© PLUS-ONE Gallery

In several paintings there is snow on the branches, and icicles hanging in the foreground, as if the sheets of rain have now frozen. These paintings feel even more enclosed and claustrophobic than before. But other paintings open out, such as Rising Black Lobster, in which a lobster emerges from a pond whose surface is covered in leaves, its reflection creating the impression of a symmetrical, double-headed animal.

Legiers is often framed as a particularly Belgian artist, thanks in part to the mussels, the rain, and his evident debt to surrealists such as Magritte. But seeing his work in an Asian context brings to mind the tradition of Japanese and Chinese carp painting, the fish at once symbolic and stylised, yet also part of the natural environment. It’s a reminder that Legiers is not just the shuffling the worn deck of cards left to us by the surrealists, but is tapping into deeper currents of representation and thought about the world.