From Balboa to Bolívar: the South American Dreams of King Leopold III

Some finds from a forgotten archaeological adventure are hidden in the bowels of the Art and History Museum in Brussels’ Cinquantenaire Park. In 1956, a largely Belgian expedition searched for a mythical city in the Caribbean that had disappeared from the face of the earth. The great driving force behind this mission was the deposed King Leopold III, who had lost his heart to this part of the world. His South American travels of the 1950s were remarkable in more ways than one. He “discovered” a lake in Venezuela, met former SS officers and was immortalized by Gabriel García Márquez.

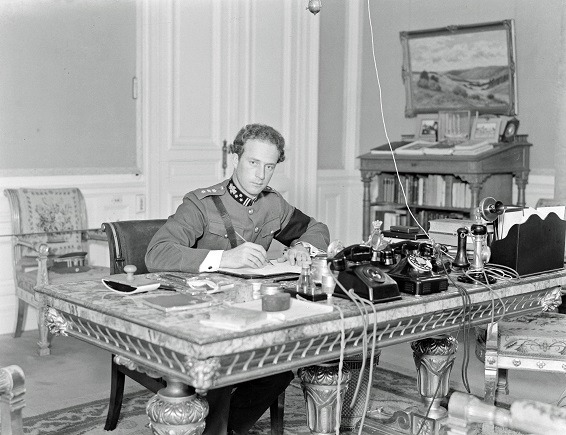

King Leopold III of Belgium at the Royal Palace in Laeken in 1934, the year he ascended the throne

King Leopold III of Belgium at the Royal Palace in Laeken in 1934, the year he ascended the throne© Wikipedia

Entire volumes have been written about Leopold III, but almost all focus on the Second World War and the Royal Question. After Leopold’s abdication, however, historians seem to have collectively laid down their pens, so that what he did after 1951 is surprisingly sparsely documented. Within six months of his deposition, he was on a boat bound for the Caribbean, accompanied by his wife, Liliane. Leopold was in his early fifties and searching for new meaning in his life. Although he travelled as a private individual, he was still received in Aruba by the local Lieutenant Governor. On 25 March 1952, he sailed to Santa Marta in Colombia, a dusty coastal city on the Caribbean Sea especially famous because it was there that Simon Bolívar had taken his last breath. The Liberator was barely 47 when he died in 1830 on the nearby estate of San Pedro Alejandrino.

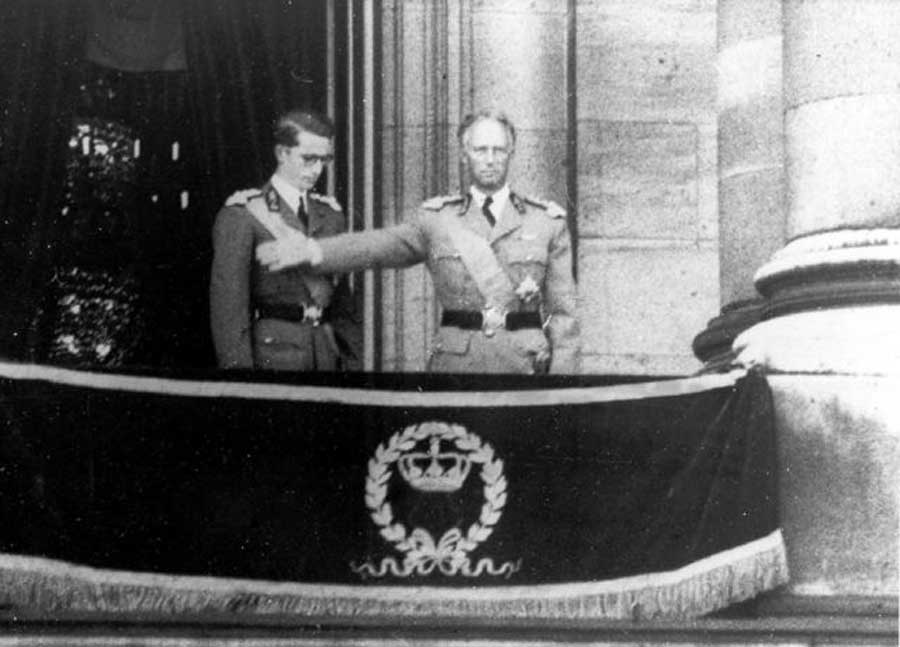

Due to a political disagreement known as the Royal Question, King Leopold III abdicated in 1951 in favor of his son, Baudouin.

Due to a political disagreement known as the Royal Question, King Leopold III abdicated in 1951 in favor of his son, Baudouin.© Wikipedia

Bolívar’s body was later transferred to his hometown of Caracas. There is no end to the squares and busts dedicated to him throughout South America and no nuance is applied to his heroic status. The Colombian painter Andrés de Santa Maria, who lives in Belgium, was once commissioned for a triptych of the Battle of Boyacá. Still, his painting was so lacking in military romance – featuring a worn-out Bolívar sitting pale-faced on his horse – that it was met with near hostility. García Márquez experienced the same rancour when he wrote a novel about the hero of independence in 1989. In The General in His Labyrinth, Garcia Márquez portrayed Bolivar as a man of flesh and blood, with weaknesses and vices, which was enough to anger many a reader in Colombia.

Characteristic of the sacrosanct dealings with Bolívar was the memorial site erected exactly a century after his death – and exactly at the place of his death. When I entered this mausoleum-like complex in Santa Marta, it reminded me of some sort of communist shrine. A rectangular forecourt with parallel palm trees and national flags leads the visitor on to a massive structure called the Altar of the Fatherland. Inside that shrine stands a life-size, marble sculpture of the Liberator draped in a toga and with the stone-cold gaze of a Roman senator. The complete lack of human warmth makes an abstraction of the tropical sun warming your back while you view the statue.

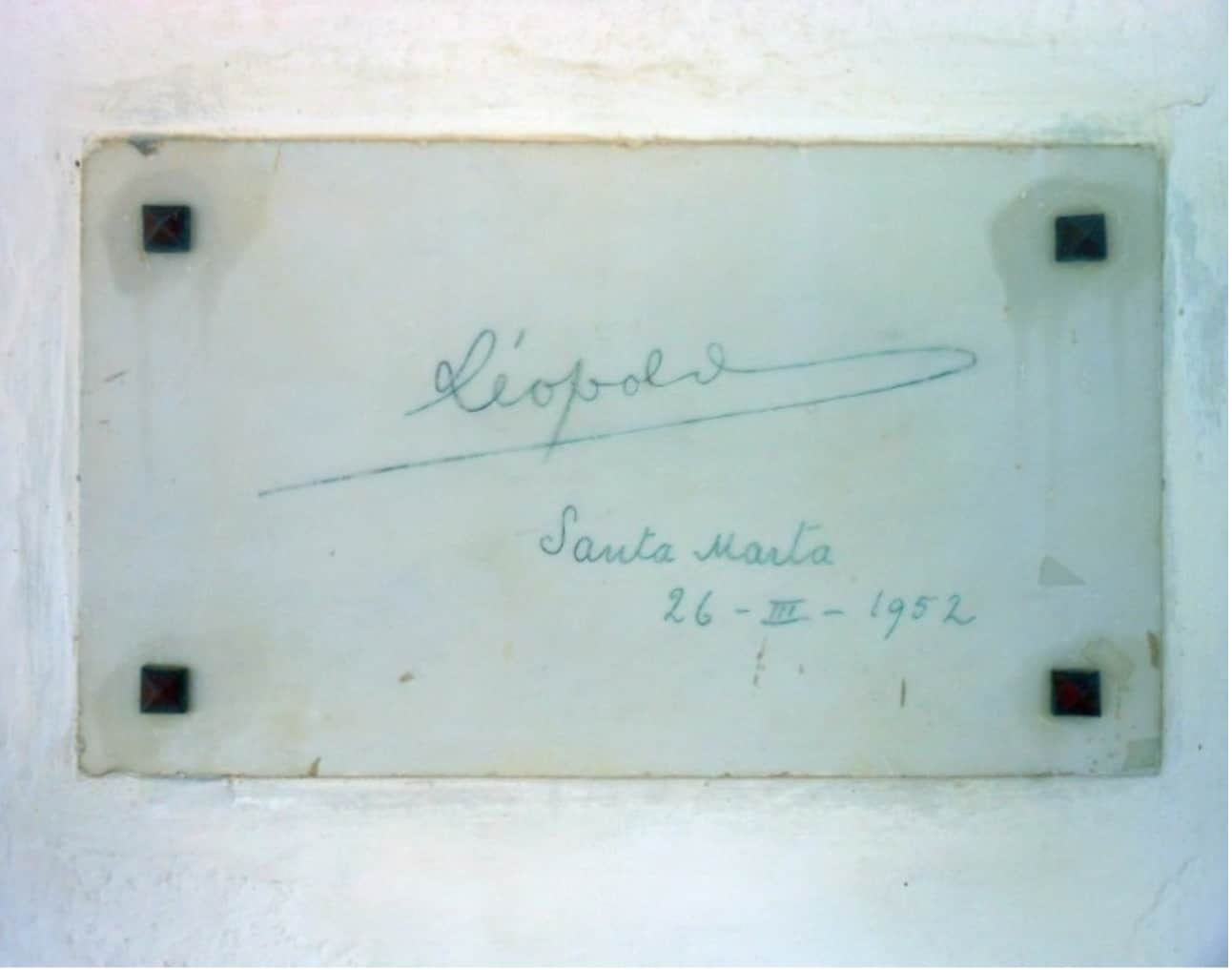

If it’s true that every human life is littered with shreds of chance, I certainly got more than my fair share here. As I looked, becoming less and less interested in a motley collection of memorial plaques in an arched gallery behind the Altar, my eye suddenly caught sight of something that seemed strangely familiar. Leopold had not only visited here on 26 March 1952 but had also had his presence immortalized! Why had I never read anything about that? Did people know about this? While I agree that Santa Marta is a distant, not very attractive corner of a country that had been cut off from the outside world for decades because of war and conflict, the forgotten existence of this stone still stunned me and suddenly seemed to reduce my surroundings to a kind of background noise.

Signature of the abdicated King Leopold III of Belgium on the wall of Simón Bolívar's mausoleum in Santa Marta, Colombia

Signature of the abdicated King Leopold III of Belgium on the wall of Simón Bolívar's mausoleum in Santa Marta, Colombiarrta

Eight thousand kilometres from Brussels, Leopold had left his signature, almost literally in the shadow of Latin America’s greatest historical figure. So soon after his abdication, this could only have been a conscious statement – as if the former king was symbolically claiming his place in the world. There was a deliberately sought-after parallel lurking in that Colombian footprint: Bolívar died in 1830, the very year Belgium came into being, at a time when Bolivar, like Leopold, had fallen into disfavour with his compatriots.

Lake Leopold

Leopold’s brief visit to Colombia was noted in the local press. A young Caribbean newspaper journalist – the then completely unknown Gabriel García Márquez – seized the opportunity to write an ironic, humoristic piece:

-

-

- A sweet lady, seemingly very concerned about the rising prices, sighed yesterday: “If that man had left me his kingdom…” She referred, of course, to ex-King Leopold of Belgium, who, as we know, left his royal palace to spend miserable nights among the mosquitoes, wild beasts, natives and malaria of the South American jungle. Ladies like her naturally have a one-sided view of wealth and monarchical authority, just as ex-King Leopold is very likely to have the equally one-sided and romantic image that certain film makers emphasise in their interpretations of South American jungles.

-

The main focus of Leopold’s journey was not in Colombia but in Venezuela, deep in the Amazon forest in the basin of the Casiquiare and Upper Orinoco. He navigated winding rivers in a virgin heart of darkness in a motorized boat. Native American helpers used machetes to cut the expedition’s way through a wall of ferns and creepers between mossy rocks. Some landmarks had never been described before. The team of scientists who were along for the adventure even managed to map an unknown lake that, to this day, is named after the most famous participant of the expedition: Lago Leopoldo.

Lago Leopoldo (Lake Leopold) in the Venezuelan Amazon

Lago Leopoldo (Lake Leopold) in the Venezuelan Amazon© Wikimedia Commons

Elsewhere in Venezuela, Leopold sought out the German zoologist Ernst Schäfer who had led a scientific expedition to Tibet in the 1930s (under the auspices of Heinrich Himmler) and had been the SS-Sturmbannführer during World War II. Given Schäfer’s own burned reputation – despite having been acquitted by an American tribunal – the meeting did not seem like a wise move on Leopold’s part but, in fact, the two clicked. Two years later Leopold would invite the German and his family to Belgium. He housed Schäfer in the royal castle of Villers-sur-Lesse and sent him to the Belgian Congo to work on a documentary. That film, Les Seigneurs de la Forêt (Masters of the Congo Jungle), released in 1958, was a prestigious production, the English version of which was recorded by none other than Orson Welles. Schäfer either enjoyed sufficient royal protection, or the Belgian press practiced self-censorship, because only the communist paper Le Drapeau Rouge really made a fuss about Schäfer and his film.

In the footsteps of Balboa

In February 1954, Leopold departed on a second expedition to South America. This time, he seemed strongly attracted to the figure of Vasco Núñez de Balboa, the Spaniard who had been the leader of Santa María de la Antigua del Darién at the very beginning of Spanish colonisation of the mainland of the New World. Above all, Balboa was a legendary explorer, the first European to reach the Pacific Ocean in 1513. A discovery that, at that time, was almost as noteworthy as the discoveries of Columbus.

A Shakespearean drama ensued. Spain had sent a new governor to Santa María who, consumed with jealousy, was deeply at odds with Balboa. The nefarious Pedrarias set a trap, and Balboa was arrested and accused of rebellion. Balboa’s head landed first on the chopping block and was afterwards set on a spike. This was, then, the end of explorer but also the end of Santa María. To Pedrarias, the settlement symbolised Balboa and had to be wiped off the face of the earth for that reason alone. He founded a new city elsewhere, which he named Panama. In no time at all, the jungle began to obliterate fifteen years of human activity. The doomed Santa María was never rebuilt and eventually disappeared from the map.

Leopold was attracted to the Spanish explorer and conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475 –1519), who is best known for being the first European to lead an expedition to have reached the Pacific Ocean.

Leopold was attracted to the Spanish explorer and conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475 –1519), who is best known for being the first European to lead an expedition to have reached the Pacific Ocean.© Wikimedia Commons

For a long time Balboa was regarded in historiography as a rebel and ‘good’ conquistador, at least in comparison with crueller representatives of colonisation such as Cortés and Pizarro. Stefan Zweig wrote a lyrical piece about the discoverer of the Pacific Ocean. Pablo Neruda – not exactly sympathetic to the Spanish conquerors – once wrote a ‘Homenaje a Balboa’ (Homage to Balboa). That this man somehow attracted Leopold is therefore not surprising. At the risk of taking a cheap psychological shot, I wonder if he saw the betrayal that had destroyed Balboa as anything more than a historic event? Did the story touch the dethroned king on a more emotional level?

In 1954, Leopold wanted to trace Balboa’s route – albeit in the opposite direction, departing from Panama. He was accompanied by José Cruxent, a native Catalan archaeologist who had also been on the expedition in Venezuela. On 25 April 1954, amid thunder and rainfall, an eleven-member party climbed a hill that Cruxent believed was the very spot where Balboa had first glimpsed the Pacific Ocean. The Kuna Indians who travelled with them chopped away at vegetation to give shape to the miracle. Everyone sensed the weight of the moment. Four flags were promptly raised in the air: Spanish, Panamanian, Venezuelan and, of course, Belgian. After a few speeches and a bottle of rum, Leopold pinned the name Cruxent on the spot, a gesture that moved the Spanish Venezuelan very much.

But merely following in Balboa’s footsteps had not satisfied Leopold. The mystery surrounding the explorer’s death had a hold on him: he wanted to find the exact place where the Spanish royal drama had taken place. That became the plan for a new expedition two years later.

After his abdication, Leopold traveled the world with a camera in hand. He had a deep passion for nature and anthropology. His encounters with indigenous peoples, such as the Kuikuru in Brazil, not only reflect his interest in different cultures but also his desire to capture the world in a way different from that of a monarch.

After his abdication, Leopold traveled the world with a camera in hand. He had a deep passion for nature and anthropology. His encounters with indigenous peoples, such as the Kuikuru in Brazil, not only reflect his interest in different cultures but also his desire to capture the world in a way different from that of a monarch.© Leopold III Fund

Historical sensation

Santa María must have been somewhere in the armpit between Panama and Colombia. According to chroniclers, the settlement had been looted, burned and left as a strip of scorched earth in 1524. Nearly all the buildings had been made of wood and had given up their secrets to the flames. What could Leopold still hope to find in 1956? He regularly explored the area by helicopter and listened to residents. Several Belgian historians and archaeologists had travelled in his wake, and he had also called on a renowned Austrian scientist who had lived in Colombia for years. Unlike Schäfer, Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff seemed to have an impeccable reputation – he had received medals for this work with the French Resistance in Colombia. Yet, years after he died in 1994, it would be discovered that he, too, the father of Colombian anthropology, had had a hidden and violent past as an SS man.

On 30 January 1956, the expedition unexpectedly came across a stone ruin. Leopold was convinced that he had found the original remains. ‘Curious impression’, he wrote laconically in his logbook, but this ruin was an unadulterated historical sensation: it was located in the oldest European city on the American mainland. The accompanying archaeologists set to work and uncovered fragmentary remains of stone structures. But less than three weeks later, the excavations (in which Leopold himself did not participate) were stopped, reportedly at the order of Colombian President Rojas Pinilla, who feared that the Belgians would remove great treasures. The treasure seemed highly exaggerated: according to Le Soir, the harvest consisted mainly of earthenware pots, a dagger, an axe, a stirrup and some nails. The fact that the artifacts in the Cinquantenaire Park are in deep storage and not available for public viewing may speak volumes.

In 1956, Leopold went on an expedition to Colombia in search of traces of the lost city of Santa María.

On 14 February 1956, Leopold was received by Rojas Pinilla in Bogotá. The Colombian president – in fact, a military dictator who would disappear from the scene a year later – made him wait an hour and a half. Their interview, in a study with a portrait of Bolívar on the wall, was brief but otherwise amicable. Leopold noted his shock at the dilapidated state of the presidential palace. Santa María continued to fascinate archaeologists throughout the following decades. It would not be precisely located until half a century later. Since 2019 it has been a National Archaeological Park, open to tourists.

Up until he became very elderly, Leopold (1901-1983) would make many distant and adventurous journeys, although after the 1950s he ignored this corner of South America. His travel diaries were published posthumously, edited and with omissions, and certainly did not answer all the questions. Leopold’s expeditions, like so many other episodes in his eventful life, remain shrouded in mystery.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.