Belgium and the Netherlands have nothing to be ashamed of when it comes to LGBTQ+ film festivals. The initiatives are many and varied, and while their aim is obviously to showcase the work of filmmakers, their role goes beyond simply screening films. Several festivals play a crucial role in providing refuge and support for LGBTQ+ people.

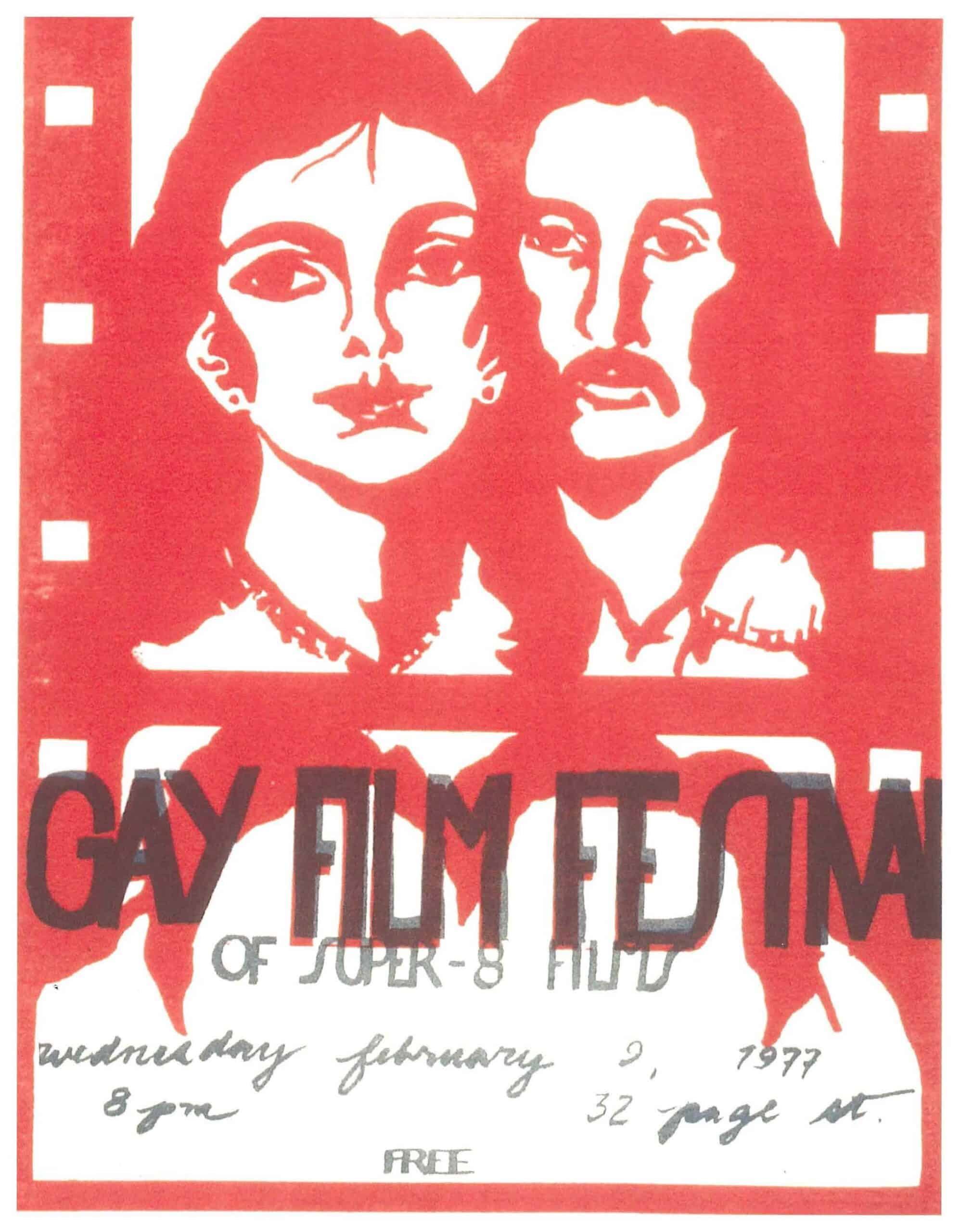

On 9 February 1977, hundreds of film lovers flocked to the dance studio of choreographer, performer and teacher Ed Mock for an event that marked the beginning of the world’s first official gay film festival. Run entirely by volunteers, and with a line-up of twelve films by makers from across the Bay City area in San Francisco, The Gay Film Festival of Super-8 Films sought to showcase the richness of home-grown talent, while bringing together gay communities under the banner of cinema.

Poster for the first Frameline festival, held in 1977

Poster for the first Frameline festival, held in 1977Its immense popularity saw the volunteer collective organise three further exhibitions of queer film that same year, with word spread by the stories of enthusiastic visitors and flyers pasted on telegraph poles. In the years that followed, these local screenings flourished from their humble beginnings into the world-famous ten-day annual event that has since become known as Frameline:

San Francisco International LGBTQ+ Film Festival.

Now featuring over 200 films from 34 countries and receiving between 60,000 and 80,000 visitors annually, Frameline is the largest LGBTQ+ film festival in the world and has helped pave the way for similarly popular events globally. Several of these are active in the Netherlands and Belgium, where they function to unite queer and trans filmmakers, audiences, activists, and allies, while also serving as a vital part of the (inter)national cultural landscape.

A sketch

In 1986, less than a decade after Frameline took shape in San Francisco, the first International Gay and Lesbian Film Festival Holland (IGLFFH) was held in Amsterdam. Launching with an ambitious two-week programme, the festival ran successfully for two editions before funding issues put paid to the project in 1996.

Following the loss of this important cultural event, the Roze Filmdagen (Pink Film Days) surfaced in its place to demonstrate “through a diverse programme, the diversity of the (LGBTQ+) community”. The first four-day festival was planned in June, around commemorating the Stonewall Riots and Amsterdam Pride. Since 2010, however, it has taken place annually in March and fills its eleven-day event with over 130 films from across 40 countries, workshops, Q&As and parties, and regularly attracts some 10,000 visitors.

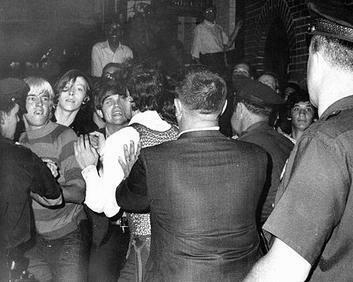

The only known photo of the Stonewall riots, a series of spontaneous demonstrations by members of the gay community in response to a police raid on the Stonewall Inn in New York in June 1969.

The only known photo of the Stonewall riots, a series of spontaneous demonstrations by members of the gay community in response to a police raid on the Stonewall Inn in New York in June 1969.© Wikimedia Commons

In addition, the annual International Queer Migrant Film Festival (IQMF) has been contributing to the Dutch LGBTQ+ festival scene since 2015 with a five-day programme that runs between March-April. Launching their own cinema space in Amsterdam in 2021 – the Supernova Cinema – the collective behind IQMF focuses their programme on themes of intersectionality, decolonisation and commemoration, and offers workshops and events that aim especially to reflect the sexual diversity of queer and migrant communities and to move beyond Western binary logics.

Also located in the Dutch capital is TranScreen, Europe’s longest-running film festival for transgender, gender non-conforming, nonbinary, and gender-queer filmmakers and their works. Taking on the mantle of the Dutch Transgender Film Festival in 2009, which had already been running since 2001, the volunteers of this biannual event aim to “increase (awareness of) gender diversity, visibility, acceptance and empowerment of trans and gender diverse people” through their global film programme. The team supplements its four-day event in May with screenings and events taking place in cities across the Netherlands throughout the year.

Poster for the 2020 edition of the International Queer Migrant Film Festival

Poster for the 2020 edition of the International Queer Migrant Film Festival© Daniel Arzola

The Holebifilmfestival, the biggest LGBTQ+ film festival in Belgium, has been in existence since 2001 and adopts a similarly inclusive geographic strategy. Held every year in November in Leuven, the Holebifilmfestival screens films in parallel in thirty-five other cities across the country during its two-week programme. Like festival planners in the Netherlands, the organisers of Holebifilmfestival

hope to celebrate the strides that have been made for LGBTQ+ rights since Stonewall, while raising awareness of the continued need to unite queer people in the fight for the right to exist.

Association Genres d’à côté also harnesses the power of film for activist purposes, during their festival Pink Screens. Growing from a three-day festival in 2002 to what the programmers now describe as a ten-day “delicious menu of fiction, documentaries, experimental films, shorts and features, debates, surprising encounters, parties and exhibitions.” Pink Screens deploys its November programme in Brussels to assault and deconstruct the binary normality (female/male, male/female, homo/hetero, dykes/queers, trans/bio) and to promote dialogue across queer and non-queer communities.

This “pinking” of the Belgian festival circuit is further enriched by PinX in Ghent, an event that celebrated its eleventh edition in February 2024. For the organisers of PinX, the screening of LGBTQ+ films is one way of creating realistic counter-knowledge that can challenge the troubling stereotypes that are still found in mainstream media.

The Brussels Festival Pink Screens assaults and deconstructs the binary normality

The Brussels Festival Pink Screens assaults and deconstructs the binary normalityEven this very incomplete list points to the richness of LGBTQ+ film circuits across the Low Countries, and if you visit these festivals, you will no doubt be struck by their different atmospheres and programming. Yet their origins and motivation show a fundamental unity first and foremost. That is: they are united by the ideal of a cinema made “by, for and with”.

Indeed, while the big “A-list” festivals such as Cannes and Berlinale now feature more LGBTQ+ stories than ever before, these are often premised on a view from the outside. By exhibiting works that are made by, for and with queer and trans people, LGBTQ+ film festivals instead create space for characters with complex motivations, identities and relationships. Specifically, that means screening films that show that LGBTQ+ lives consist of more than trauma and violence.

The need for “by, for and with”

Exhibiting works that explore the nuances of queer and trans lives, LGBTQ+ film festivals consciously buck mainstream media’s long history of “Buffalo Bills” and “Bury your Gays” – a history that has reduced trans and queer narratives to stories of villainy or victimhood, as vividly depicted in Sam Feder’s Netflix documentary Disclosure (2020). This is not just a matter of fair representation, however. The consequences of one-sided representation and hyper-visibility in the media are still proving fatal – perhaps increasingly so – for those most vulnerable within LGBTQ+ communities, in particular people of colour, trans folk and sex workers.

This relationship between negative media portrayals and offscreen homo- and transphobic violence has been a long-standing concern for LGBTQ+ festival programmers. The team behind the TranScreen film festival in Amsterdam, for instance, contends that “bad/poor media representation drives transphobia and [has] a negative effect on the lives of trans people”. Dutch writer, programmer and journalist Teddy Tops similarly argues that nuanced and consensual visibility might help combat societal discrimination. “As long as there is aggression against people like us,” Tops writes, “it is necessary to create visibility, venue by venue.”

For many LGBTQ+ festivals, promoting the right kind of visibility starts with the spirit of the San Francisco Super-8 festival: screening and supporting films made “by, for and with”. This project often includes programming policies that reject films made by heterosexual or cisgender directors, although this is not the case for all LGBTQ+ festivals.

The principle of “by, for and with” is also important for another reason. Discrimination does not stop at the threshold of arts and culture foundations. Queer and trans filmmakers not only experience discrimination in the job market but, far too often, queer or trans-made projects appear to fall outside of the category “Film” and are dismissed by funding bodies as “amateur” or “niche” works.

For many LGBTQ+ festivals, promoting the right kind of visibility starts with screening and supporting films made by, for and with LGBTQ+ people

Not incidentally, a similar fate befalls LGBTQ+ festivals as they struggle for funding each year. In this way, dedicated financial aid and networking opportunities provide much-needed support to queer and trans filmmakers. For example, the global distributor Frameline Distribution, connected to the San Francisco festival, caters solely to LGBTQ+ films. Much closer to home, the International Queer Migrant Film Festival’s series of workshops and networking sessions for emerging filmmakers in the Netherlands helps orchestrate exchanges between local filmmakers and international artists and festivals.

By stimulating and supporting community-made films, then, LGBTQ+ film festivals offer visitors access to new and underfunded makers, who can provide us with the tools to expand our cinematic and social horizons. Yet, it is the continued care with which all this is achieved that is perhaps the most striking aspect of LGBTQ+ festival programmes.

A cinema of care

“We are a community that cares” announced dramaturg and festival co-organiser Selm Wenselaers during the opening speeches of TranScreen in May 2023. Judging from the cheers that erupted from the sold-out auditorium, the audience certainly agreed.

LGBTQ+ film festival organisers do not only care about the representation of queer and trans lives, however. They also care deeply for

their filmmakers, their audiences, and the small team of volunteers that works tirelessly behind the scenes. This dedication to caring for people manifests itself in several visible ways.

Many festivals outlined in this article, for instance, ensure that their ticket prices remain modest or include pay-it-forward schemes for those with low incomes. In some cases, free tickets are made available for LGBTQ+ refugees. As an increasing number of filmmakers and audiences cannot afford to participate in international film festivals such as Sundance

and Telluride, these forms of financial care become crucial, especially since LGBTQ+ individuals – migrants, especially – more frequently face precarious financial situations due to societal marginalization and workplace discrimination.

Depicting the complexity of queer and trans lives does not mean avoiding difficult subject matters

Festival workshops, meet-and-greets, exhibitions and parties are also acts of community care. These additional events create space for making new acquaintances, finding support from fellow queer and trans folk, as well as providing the necessary time for visitors to share their own stories. Aftercare is also starting to become a central part of the festival programme.

Depicting the complexity of queer and trans lives does not mean avoiding difficult subject matters. Quite the contrary, in fact. And films that portray forms of violence that you have experienced yourself can be hard-hitting. Accordingly, time and space are frequently set aside to allow audiences to process the screening, by providing a guided audience conversation, for example, or a quiet space to reflect.

In this way, LGBTQ+ film festivals are putting themselves at the forefront of person-centred film and arts programming. Thus, while some Dutch and Belgian organisers may long for a future in which dedicated queer and trans festivals are no longer needed, their very events are making abundantly clear that there can be no future for cinema without the people by, for and with whom it is made. No future for cinema without care.