Lieke van der Made Edits Reality

How can we make large, complex issues – such as the conflicts in the Middle East – more manageable? Dutch artist Lieke van der Made (1992) discovered that by editing footage, her videos could achieve these ends. Once she had realized this, her switch to collage techniques made perfect sense. In her collages, Van der Made combines various voices and history into a new whole that invites further research.

Lieke van der Made wanted to experience for herself how daily life in Jerusalem, which she only knew from often diametrically opposed stories from the global news, looked like. She ended up in a collage-like city: divided into East and West Jerusalem, which were also divided into all kinds of districts, zones and areas. Yet, they all seemed to work together, she remarked. In 2014, she stayed in Jerusalem as an exchange student. Among other things, she shot images for the video The Big Balagan (2014) there. Completely in line with the title – balagan is Modern Hebrew for chaos – the video had a disorienting effect: the viewer constantly received new impressions to process, as if he himself was also walking through a city unfamiliar to him.

Clever editing

At first glance, The Big Balagan consists of two screens. Both show a different stream of (city) images that sometimes seem to have little in common. Often recurring is footage of pedestrians, whose legs and feet are mainly shown. After a number of these passages, the camera follows the same body on one of the screens, from feet to neck – never a face on screen. Then one hand holds a card on the other screen that reads: I notice people staring at my legs all the time. Suddenly you feel like a voyeur, while you thought you were watching with someone.

Clever film editing enables such an unexpected change of perspective. Van der Made is very interested in this phase of filmmaking, which can be seen in her videos. For The Big Balagan, for example, she initially shot as many images as possible in Jerusalem, without a specific goal. While editing the footage, she was able to create new contexts in which these images acquired meaning and function in a larger whole. In this sense, the montage reflects the way in which the news supply works.

News papers and other media work in a similar way: they reorder large amounts of information into compressed stories which – however much and however often they claim to be objective – ultimately always colour the truth, precisely through that selection of information. Van der Made does something similar in her videos, however she does not arrange her material into a narrative, but rather into an associative whole. The interrelationships sometimes only become clear after, and are often based on visual rhymes; for example toes and treetops. In a certain way it feels honest: art that shows that the world is fragmented, and how you can attempt to (partially) organize or understand it.

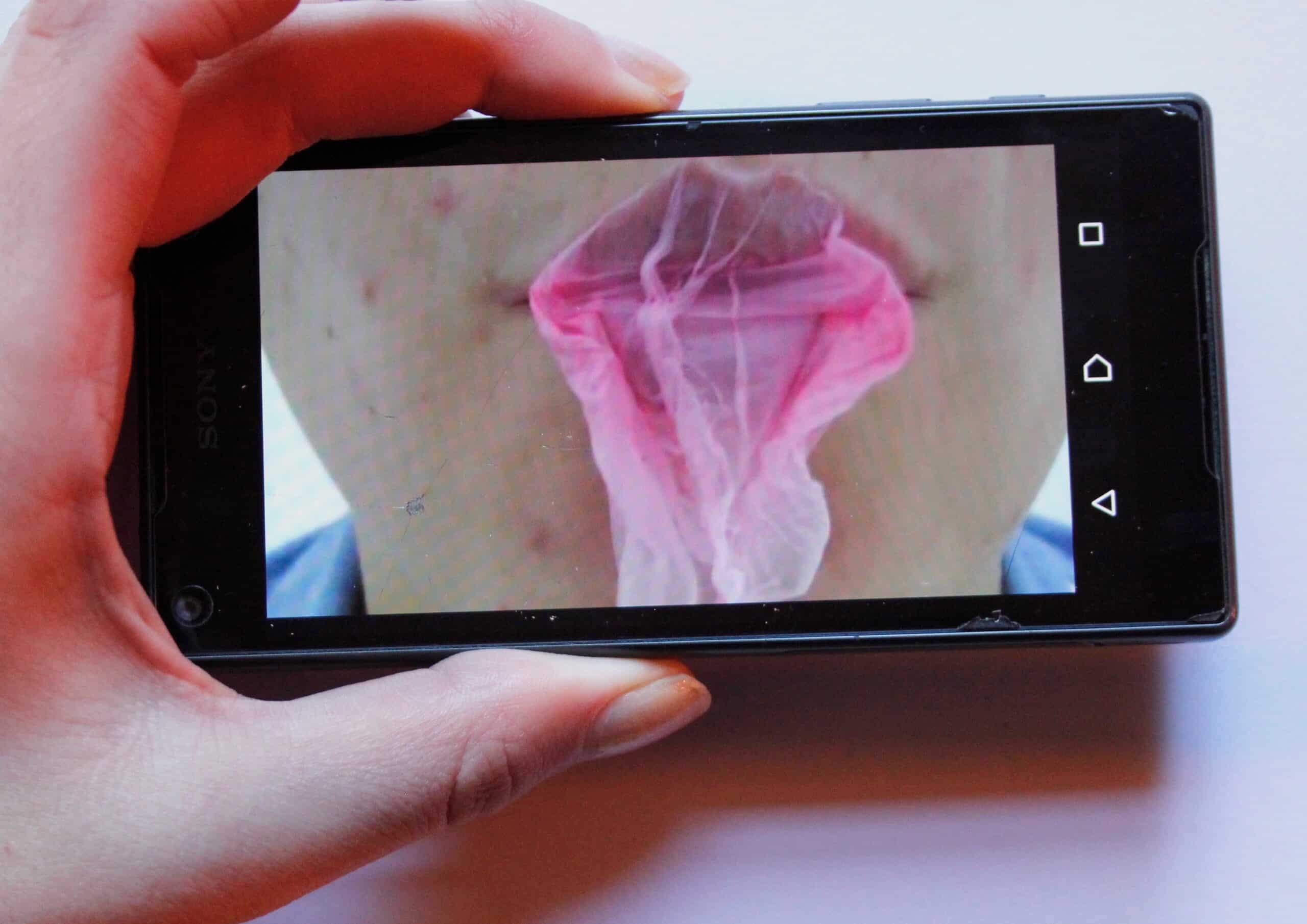

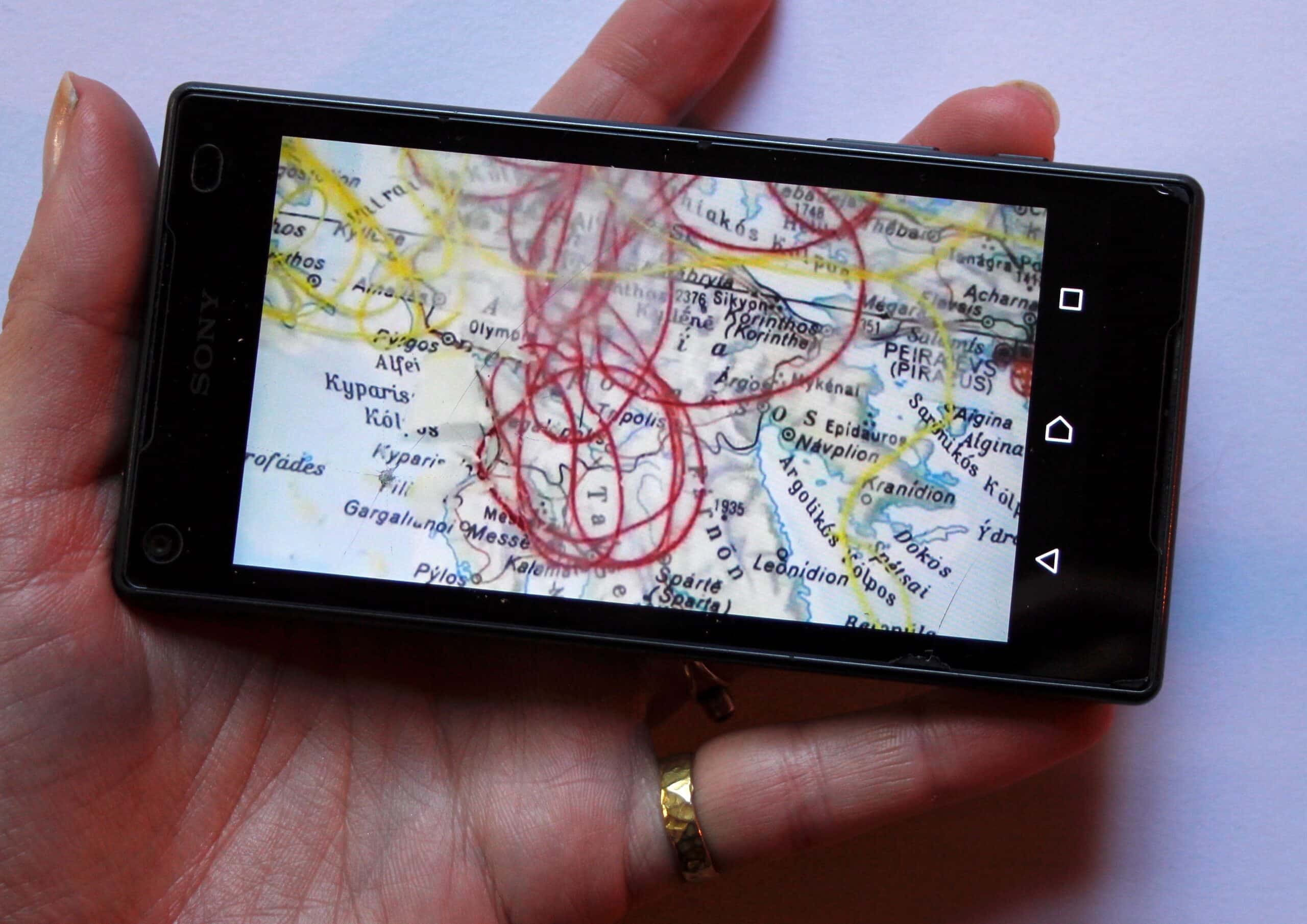

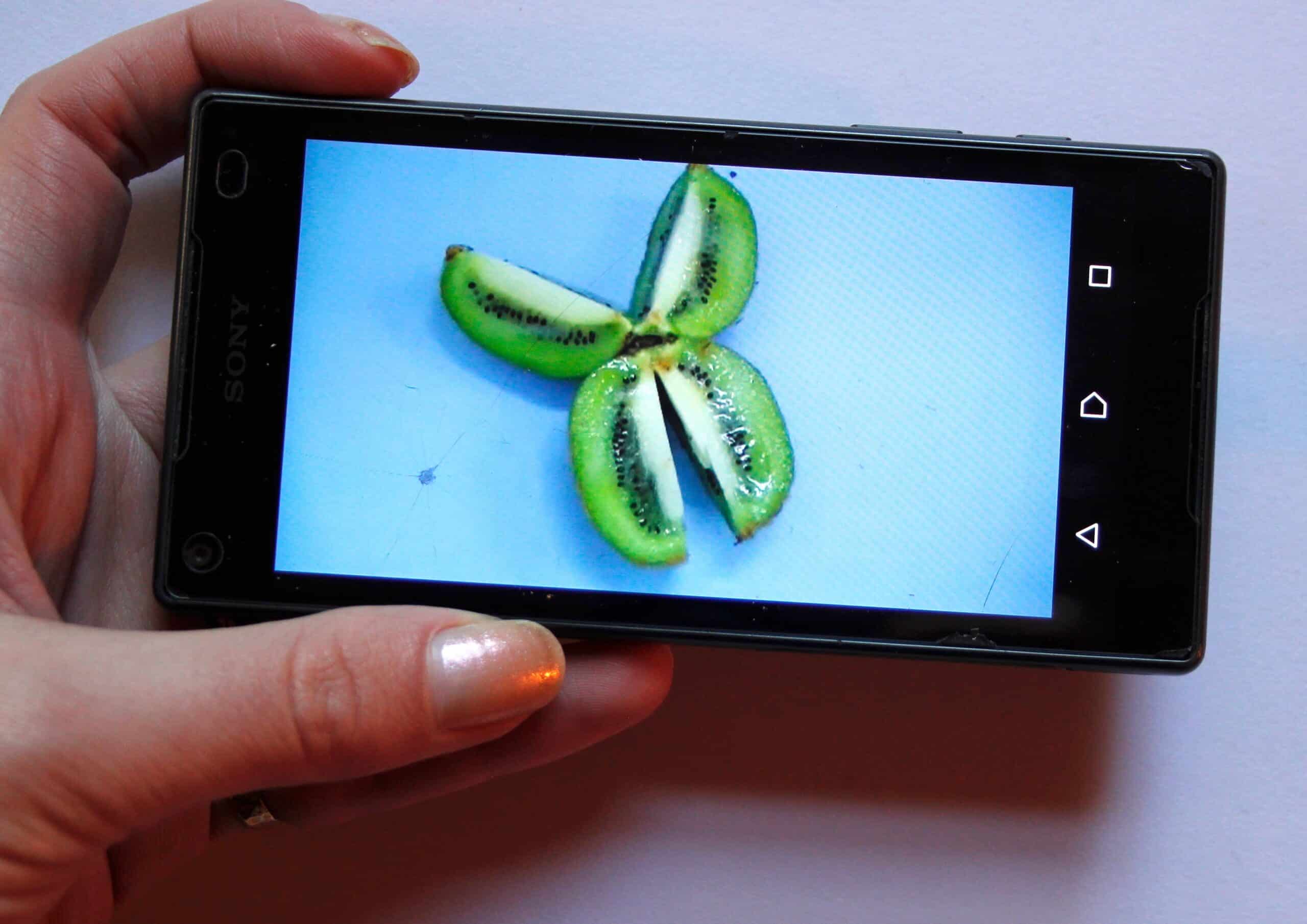

Lieke van der Made, De aarde is plat (the earth is flat), still 1, 2, 3, 2013

Lieke van der Made, De aarde is plat (the earth is flat), still 1, 2, 3, 2013© Lieke van der Made

Attempts can fail; she shows in the witty video De aarde is plat #1 (2013), which is remarkably topical in times of fake news. The video shows someone who claims that the earth is flat: just look at the atlas. To illustrate this, a map is cut out. Moreover, the fragmented way of working ensures that “the whole” – or at least a possible reading of it – perhaps arises just as strong in the mind of the viewer as in that of the artist.

Image collision

After producing several playful, associative videos, Van der Made tried to find a “static” medium in which she could work in multi-layered ways. The result was collage. There are roughly two “traditions”, which both go back to dada: the surrealistic variant in which it revolves around the alienating collision of two unrelated images. The incorporation of the outside world is of secondary importance. For the second variant – think pop art, nouveau réalisme – this annexation was of great importance. Essential here, is to not lose touch with the outside world.

At first glance, Van der Made works in the Dadaist-surrealist collage tradition: she often juxtaposes very different images, making them look alienating. Fig. 67/68. Funerary 2006-2016 shows a group of age-old sculptures against a contemporary desktop background, icons included (2018). However, this collage is by no means without an outside world: the chosen elements are closely linked to history and current events. The image collision refers to the disturbing development that such artefacts are (partly) destroyed, as a result of which they start to lead a largely digital life – on screens.

Lieke van der Made, DGTTL_HRTG, Fig. 67/68. Funerary 2006-2016

Lieke van der Made, DGTTL_HRTG, Fig. 67/68. Funerary 2006-2016© Lieke van der Made

The above collage is from the series DGTTL_HRTG (digital heritage) from 2018. It’s part of Van der Made’s graduation project for her master’s in Artistic Research – the university continuation of her studies at the art academy- for which she also wrote a thesis on digital ways of preserving eastern heritage, particularly in the interest of the iconoclasm of the Islamic State (IS). She came across an uncomfortable point of view with which she doesn’t agree, but that do give her collages a penetrating extra layer: it is perhaps a good thing that many Eastern artefacts have been shipped to Europe and America, so that they could – unintentionally, admittedly – be protected from destruction by IS.

Such themes are very sensitive, especially in an art world that abundantly highlights cultural appropriation and identity issues. Van der Made has also experienced several times that discussions arose with her and about her work, for example with a fellow student who was very occupied with her own position as a white person. On the other hand, Van der Made also spoke to a Syrian archaeologist who was positive about her work. One could just as well say that the way in which the West deals with such heritage and incorporates it into its own system and (art) history is a Western matter.

Lieke van der Made, DGTTL_HRTG, Uran 6, 2018

Lieke van der Made, DGTTL_HRTG, Uran 6, 2018© Lieke van der Made

Polyphonic

Van der Made’s collage technique is perhaps best seen as a way of incorporating all kinds of other voices and histories into her own work of art, and thus trying to look beyond her own Western view. In DGTL_HRTG different domains directly oppose, or overlap each other: the West and the East, current affairs and history, the digital and the physical. As in her videos, new connections are made and (familiar) visual elements are rearranged. The difference is that the collages feel more accurate: Van der Made makes clearer connections; she doesn’t shy away from political issues, but never becomes preachy. Rather, she reveals underexposed or hidden relationships, to make the audience stop and think.

A perfect example is Nineveh and its Remains 110009,a (2018). The basis is a black and white drawing by white colonialists who have the indigenous population move a large, sphinx-like sculpture. This image is combined with a coloured image of a similar sculpture with museum signs on both sides. The uncomfortable relationship between the two elements is clear: what can be seen in a Western museum in oriental artefacts and art has been removed elsewhere. This goes beyond pure images that come together: it’s a clash of cultures and times – and perhaps most of all, a clash of perspectives and representations.

Lieke van der Made

Lieke van der Made© Sebastiaan ter Burg

Van der Made finds the origin of the visual material so important that she doesn’t use images of which she doesn’t know the background. When she comes across an image in one of her archives of which she cannot remember its origin, she does a reverse image search on Google to update herself. The titles of the DGTL_HRTG-collages often refer to quotations, book titles, and archive numbers, which explain remarkable names such as Fig. 67_68. Funerary 2006-2016 and “Discard that the returned pieces are exposed to risks”.

All these elements, both visual and textual, carry a story with them that can be unravelled. By the artist, but also by the viewer. Van der Made’s collages are compressed versions of something that is much larger and more complex, but at the same time is not irretrievably lost in her works of art. Her stimulating combinations invite us to look for the larger context.