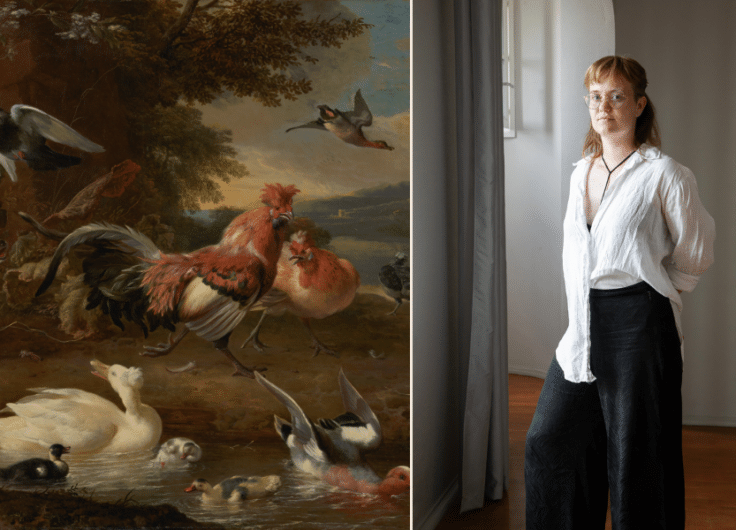

Living Masters, a New Overview of 19th-Century Painters in the Netherlands

With Mirror of Reality, Jenny Reynaerts, senior curator at the Rijksmuseum, wrote the first full history of nineteenth-century art in the Netherlands, set within the context of the international art world. It would seem that political contradictions played a less important role in the Netherlands than elsewhere in Europe.

‘While in our country we continue to tread the roads that we have travelled for years (…) there is a wonderful modernist movement flourishing in Holland’, wrote André De Ridder, an art historian from Antwerp. After his stay in the Netherlands during the First World War, he concluded that the lagging Belgian art world had catching up to do, and for many Belgian artists, enthusiasts and lovers of art, Amsterdam became a beacon of artistic progressiveness throughout the twentieth century.

Pieter Christoffel Wonder, The staircase of the painter's London home, 1828

Pieter Christoffel Wonder, The staircase of the painter's London home, 1828© Centraal Museum, Utrecht

However, up until the end of the nineteenth century, the situation was entirely the opposite: Dutch artists readily came to study at the famous Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. From the mid-nineteenth century many of them, from Willem Roelofs to Johan Thorn-Prikker, discovered artistic ideas and frameworks in Brussels for a comprehensive renewal of landscape painting. Later, during the post-impressionist decades at the end of the nineteenth century, they found a definitive departure from pure naturalism.

But the heart of the story was of course written in Paris, the then capital of art in ‘the West’. Brussels, situated halfway between Amsterdam and Paris, served as a conduit for the Avantgarde rather than a centre of it. The story Jenny Reynaerts tells in her book Mirror of Reality – a history of nineteenth-century fine art in the Netherlands – has a strong European feel, with the occasional a global tinge.

Gerard van Spaendonck from Tilburg made his career in Paris as a specialist in floral still life. It was in his studio that the Antwerpian Frans van Dael, and the Dutchman Willem van Leen learned the tricks of this lucrative trade. In Rome, Hendrik Voogd, one of the many European landscape painters in Italy, became acquainted with the German Fensterbilder. Raden Sarief Bastaman Saleh had his portrait painted as a top Javanese artist in Dresden. Ary Scheffer from Dordrecht belonged to the vanguard of Romanticism in the 1820s, as well as Delacroix and Géricault. A few decades later Johan Barthold Jongkind from Overijssel would inspire Claude Monet. Roelofs and other Dutch artists living in Brussels were included in the Belgian entry for the 1855 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Matthijs Maris from The Hague and the Frisian superstar Lourens Alma Tadema studied for a short time in Antwerp, before settling in London.

Egbert van Drielst, Dilapidated neighbourhood, 1809

Egbert van Drielst, Dilapidated neighbourhood, 1809© Kunstmuseum Den Haag

The connections between what these and other Dutch artists painted, and what their French, German and Belgian contemporaries and predecessors realised, are much stronger than the cohesion that might exist between the paintings of the Dutch Woutherus Mol, Jan Adam Kruseman, Jozef Israëls, Willem Mesdag, Suze Robertson, George Breitner or Jan Veth – all emerging over the course of the nineteenth century. After all, it was French artists and critics – Théophile Thoré-Bürger, Eugène Fromentin and Hippolyte Taine – who drew Dutch attention to the modernity of Ruysdael, Hobbema, Vermeer or Rembrandt, with Rembrandt the hero hors concours of all modern artists. Dutch pleinairists or realistic landscape painters learned from their older French colleagues how they could paint a modernised version of the seventeenth-century world of Ruysdael and Hobbema in their own country, in order to successfully sell it to British collectors such as James Staats Forbes.

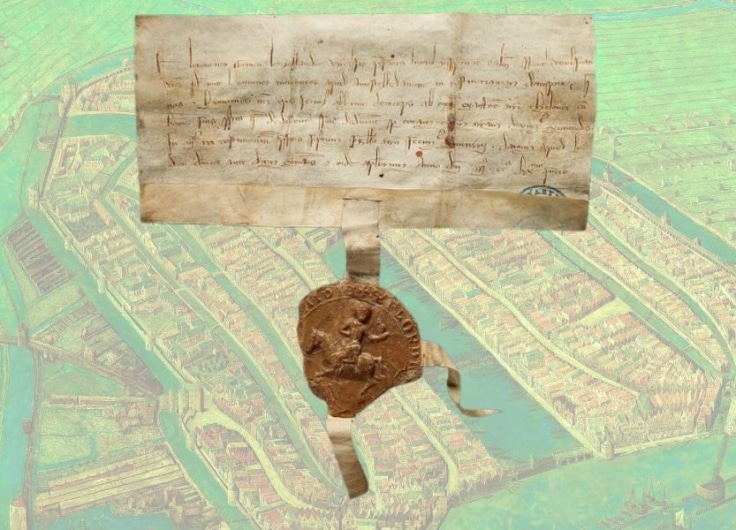

What Dutch artists did share with each other was an art world that had been dramatically re-shaped since the French occupation and annexation. King Louis Napoléon Bonaparte made plans to take the education of artists into his own hands. In 1808 he organised the first public exhibition of ‘living masters’, which was held in the former city hall of Amsterdam – a building he used as a palace and in which he had also set up a national art museum. William I, Prince of Orange would also establish a Museum for Living Dutch Masters in 1828.

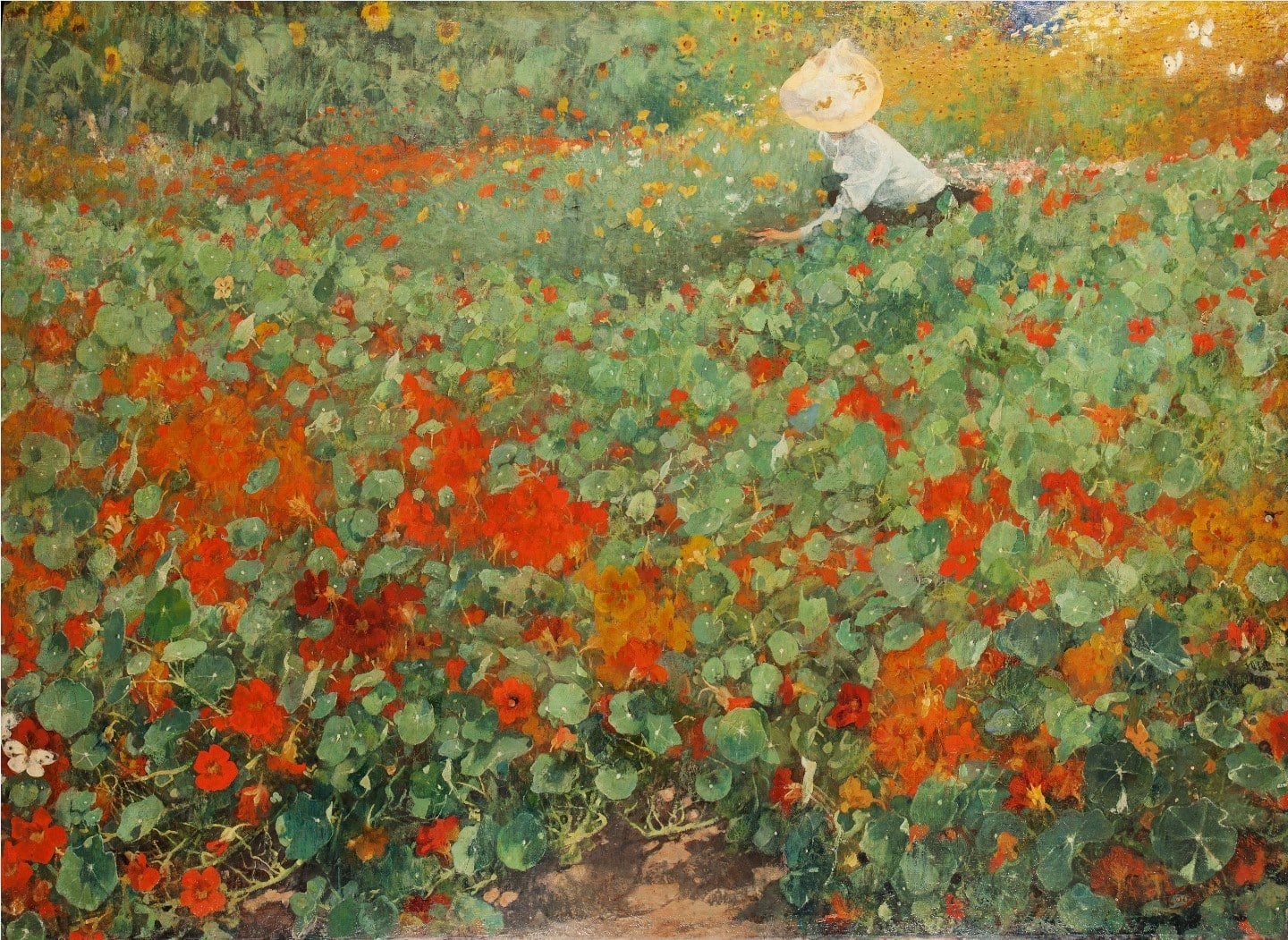

Jacobus van Looy, The garden, circa 1893

Jacobus van Looy, The garden, circa 1893© Teylers Museum, Haarlem

New and important is Jenny Reynaerts’ attention to the institutional aspects of art life and to the interaction between the various players. To begin with, there is the role of government in the organisation of art education, which until the late nineteenth century was predominantly regarded as classical and theoretical. Incidentally, girls were admitted to institutions from 1870 and from 1884 they were also able to compete for the prestigious Prix de Rome. Modern art at the time was above all considered to be ‘exhibition art’, and the eventual destination of these works has remained largely uncertain since then. Artists showed their work at the major annual art exhibitions in Amsterdam and The Hague, and from the middle of the century, work was increasingly shown within art circles such as Arti et Amicitiae (Amsterdam, 1839), Pulchri Studio (The Hague, 1847) or the progressive Dutch Etching Club (1885-96).

The distribution of artistic production was, as it were, guided by art critics such as Jacob van Santen Kolff, who from 1875 in De Banier –

the magazine for ‘young Holland’ – bemoaned the excess of vieux jeu. There was also Jan Veth, who years later in the publication De Amsterdammer

(1877) tried to convince the Dutch of the fact that visualised moods should not so much be a mirror of reality, but rather a mirror of the soul. Many citations from art critics at the time help the reader of Reynaerts’ book to understand the aesthetic expectations of nineteenth-century Dutch connoisseurs and enthusiasts. This is particularly useful because the varying success of the iconographic and stylistic trends emerging after and alongside one another other was dependant on supply and demand more than ever before. Indeed, artistic production more or less followed the growing wealth of the nouveaux riches, government financiers, businessmen as well as art dealers.

Jan Toorop, The Sea, 1887

Jan Toorop, The Sea, 1887© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Reynaerts has divided her history into four chapters. Her account is systematic, rich in information and contains excellent characterisations of the oeuvre or evolution of an artist. At the same time, she makes good use of storytelling techniques, which make her four-hundred-page book very pleasant reading. At the beginning of each chapter, we enter art history during a crucial year – 1795, 1839, 1875 and 1885. In 1839, for example, we meet Christiaan Portman, who that year exhibited three daguerreotypes for the first time, in addition to a painting dedicated to Luther.

Reynaert’s book is the fruit of renewed interest in nineteenth-century art, which is now more than half a century old and still goes hand in hand with a thorough investigation of the context in which that art originated. But unlike older publications on Dutch art of the nineteenth century, Reynaerts does not focus on providing an overview of the dialectic of alternating artistic styles. Many researchers of nineteenth-century art, particularly Anglo-Saxon researchers, have for many decades looked critically at the relationship between artistic production and critical social issues such as nationalism, social inequality and gender. Reynaerts’ colleagues have also argued that Vincent van Gogh is a thoroughly Calvinist artist and that the revival of religiosity and esotericism at the end of the nineteenth century was not ignored by artists such as Thorn-Prikker or the young Mondrian, who experimented with symbolism. But Reynaerts’ book concludes that the influence of political division between conservatives and liberals, Catholics and Calvinists in the Netherlands was generally not that important.

In fact, her book is really the first full history of nineteenth-century art in the Netherlands. She is careful not to promote a patriotic artistic canon, but the index and distribution of the more than 500 carefully selected illustrations reveal who she believes are the most important artists: Johannes Bosboom, Jozef Israëls, Alma Tadema, Veth, Van Gogh (of course), George Breitner, Matthijs Maris en Jan Toorop.

Jenny Reynaerts, Mirror of Reality: 19th-Century Painting in the Netherlands, Rijksmuseum / Mercatorfonds, Amsterdam / Brussels, 2019, 400 pp.