Every month, a translator of Dutch into English gives literary tips by answering two questions: which translated book by a Flemish or Dutch author should everyone read? And, which book deserves an English translation? To get publishers excited, an excerpt has already been translated. Liz Waters generates enthusiasm for what is considered the greatest Dutch novel of all time and for a book in which the typical Dutch landscape plays the leading role.

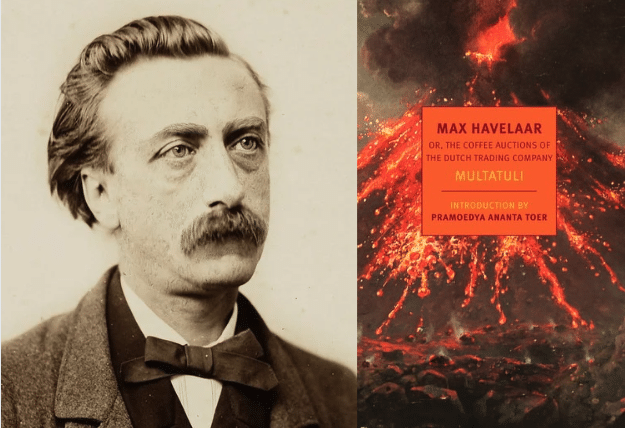

Must read: ‘Max Havelaar’ by Multatuli

Multatuli

MultatuliMax Havelaar by Multatuli (Eduard Douwes Dekker) is a literary novel that exposed the horrific abuses of Dutch rule in the East Indies. The new translation by Ina Rilke and David McKay, with its present-day tone, shows just how little the book has dated since its first publication in Dutch in 1859.

The narrative that frames the main story is irresistible. Right from that famous first line – ‘I am a coffee broker and live in a canal-side house at No 37 Lauriergracht’ – the reader is gripped by the arrogant complacency, and hilarious pomposity, of Drystubble, who is both a fully rounded character and a representative of the colonialist capitalism of the period, which still resounds in our day.

He introduces the main body of the book, a selective transcription of a mysterious bundle of papers ranging from disquisitions on grammar to poetry. We find ourselves in Java, where the system of colonial rule is laid out in colourful and horrifying detail. There are no wildly eccentric ‘Dickensian’ characters here but real people, both Dutch and Indigenous, attempting to survive and find justice in a ruthlessly corrupt and exploitative system.

In the idealistic but far from flawless Max Havelaar, Multatuli presents a believable young ‘Assistant Resident’ determined to do right whatever the cost, and through him we are drawn into the lives of the ‘natives’ to such an extent that their plight soon becomes heartbreaking.

Transcending polemic, the book draws upon the power of poetry, humour, folktales and many diverse forms of instruction and narrative. Its impact on Dutch colonial policy has been well documented, but its impact on the contemporary reader is astonishing. It remains painfully relevant, although no less enjoyable for that.

This is a work that will enthral anyone interested in the Netherlands and its history.

Multatuli, Max Havelaar. Or, The Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company, translated by Ina Rilke and David McKay, New York Review Books, New York, 2019, 336pp

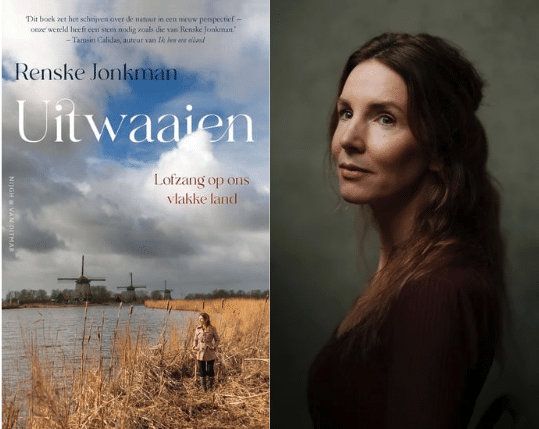

To be translated: ‘Uitwaaien’ by Renske Jonkman

Uitwaaien by Renske Jonkman is a memoir of sorts, but its focus is firmly on the Dutch landscape. Descriptions of polders, dykes or wooden windmills tend either to be technical or to presume some prior knowledge, whereas Jonkman describes exactly what she sees and explains why it’s that way and what it means to her.

Having moved back to rural North Holland from Amsterdam with her family, she makes reference to her life as a daughter, sister, wife and mother, and those narrative-rich relationships give shape to her account. But the reader is mainly drawn along by the quality of the writing, the vivid descriptions of dramatic skies, drainage systems dug by hand, the temporary nature of everything built here, and the wind to which the title refers. The verb ‘uitwaaien’ has no equivalent in English; it means something like deliberately exposing yourself to a strong blast of fresh air.

Naturally there are many references to artists and to literary works, but these are always perfectly placed, enriching the central first-person account. For English readers a translation would decrypt the manmade Dutch landscape and help to explain its effects on the people of the Low Countries down through the ages.

Renske Jonkman, Uitwaaien. Lofzang op ons vlakke land, Nijgh & Van Ditmar, Amsterdam, 2023, 176pp

Extracts from 'Uitwaaien', translated by Liz Waters, pp. 7-9 & 18-19

Westfriesland, between the North Sea and the IJsselmeer, is flat because it used to be the bed of an inland sea. Spring tides forced their way deep into the peninsula, flooding the boggy fields. The polder where I live was created four centuries ago, when the lakes and inland seas were drained. Standing in a polder, you need to visualize the fact that your feet are on the seabed. You can see for kilometres and everywhere you look are sky, clouds, dykes and ditches. The land is featureless and largely made by the people who live on it. The fields are precisely marked out and our forefathers used spades to dig the drainage ditches and raise the dykes; you can see human handiwork everywhere in the landscape.

The light in Holland has a golden colour that I’ve never come upon anywhere else. We call it Dutch light. It’s soft and diffuse, and on autumnal days it takes on the colour of the fringes of reeds along the banks of the ditches. The water of the North Sea and the IJsselmeer, of the ditches and channels, acts as a mirror that gives the air its particular glow. On dull days a bright ray of light can suddenly break through the clouds, and the light and the sky continually undergo subtle changes. The veil of mist over the meadows softens all the colours: the cows, the houses, the trees. The De Goncourt brothers, who collaborated on their literary work in nineteenth-century France, described Holland as ‘a country lying at anchor’, where the light shines as if filtered ‘through a carafe filled with salt water’.

I grew up in this region with its cool summers and mild winters, where there’s almost always wind and rain. The house where I was born is in Heerhugowaard – formerly an inland sea called De Waerdt – in a modern housing estate built between green fields. I was the youngest child of teachers, with an older sister and brother above me, and after school I liked best to spend time on the farms a few kilometres from our house, where I helped with the chores and cared for the horses, or just hung out. If I shut my eyes I can see myself cycling along the dyke against a fierce headwind, surrounded by space, the roads long and straight, the pollarded willows standing in single lines.

[…]

Danger here used to come from all sides – from the Zuider Zee, the North Sea, the IJ that forced its way deep inland – and for fear of total destruction, this polder in Westfriesland was dug out and drained by human hands, by dyke diggers, mill builders and surveyors who were the first people ever to stand on the bed of the inland sea, on muddy soil with wet clay stretching around them to the distant horizon. It must have been a desolate bare expanse when those pioneers started trying to turn the sea clay into fertile farmland in the early seventeenth century.

(The translation of this excerpt by Liz Waters in 2022 was kindly supported by the Dutch Foundation for Literature.)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.