Looted Art Must Return to Congo, but How?

All those involved agree: Belgium must return the museum pieces that were looted from Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi during colonial times. In June 2021, the government therefore decided to return the illegally obtained objects from the AfricaMuseum into Congolese hands. But that is just the beginning. Which objects are we talking about exactly? Who claims them? And what should be done with them in the country of origin? ‘Congo must have maximum access to its own heritage without logistical aspects becoming a precondition.’

The Antwerp Museum aan de Stroom (MAS) offers a good starting point for thinking about the return of colonial art. The exhibition 100 x Congo will run there until 13 September 2021: a hundred times, because a hundred years ago, in 1920, the city of Antwerp became the owner of a rare collection of art and utensils from Congo; one hundred also because the MAS presents one hundred pieces to the public.

Curator Els De Palmenaer and co-curator Nadia Nsayi departed from the conclusion that a century later we still barely know the provenance history. ‘We show pieces we don’t know a lot about,’ says Nsayi, ‘pieces we know something about, and two pieces that we are sure are looted art.’

The exhibition 100 x Congo in MAS

The exhibition 100 x Congo in MAS© Frederik Beyens

One of these, on loan from the AfricaMuseum in Tervuren, is a wooden statue, trimmed with nails and ribbons, of Ne Kuko, a nineteenth-century village chief from Kikuku, a thousand five hundred kilometres east of Kinshasa. It is the Belgian trader Alexandre Delcommune who looted the piece in 1878 in the hope that its magical power would protect his business. Seven years later, Ne Kuko was on exhibit at the World Exhibition in Antwerp, after which the sculpture eventually ended up in Tervuren. In 1973, the former Zairean President Mobutu Sese Seko laid claim to it, along with the other objects of the Art of Congo exhibition; four years ago, the current chief of Kikuku also requested the piece back.

‘We have borrowed this iconic image to be able to present the story of looted art critically and transparently,’ said the co-curator. ‘That approach is not obvious, but it does fit in a political and social context that is changing significantly.’

Power statue (nkisi nkondi) by chief Ne Kuko, Congo peoples, Kikuku, Boma region, Democratic Republic of Congo

Power statue (nkisi nkondi) by chief Ne Kuko, Congo peoples, Kikuku, Boma region, Democratic Republic of Congo© RMCA, Tervuren / Photo: Frederik Beyens

Nsayi, along with many others, is working on this change: as a political scientist and former policy officer at the NGOs Broederlijk Delen and Pax Christi, she worked around Congo, and she herself has Congolese and Belgian roots. ‘The MAS had understood from the start that there were sensitivities that it had to prepare for as a museum: the fact that many objects were brought here within a culture of totally unequal, colonial power relations.’

The expo in Antwerp comes not a day too soon. ‘When it concerns the return of colonial treasures, Belgium is lagging behind,’ said thirty-six artists, academics, and activists, most of them of African descent, in an open letter in the daily Le Soir at the end of 2018. In France, Germany, the Netherlands and other countries they had already rolled up their sleeves, according to the collective.

Not a pioneer

In France, whose colonial past, like Belgium, mainly takes place in Africa, historian Bénédicte Savoy and Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr were charged in 2017 by President Macron with the task of rolling out a plan of action for the restitution of thousands of objects. In November last year, the Senate approved a proposal by the duo to return 26 unique artefacts from the Musée du Quai Branly to Benin. This specifically concerns Benin Bronzes, much-discussed sculptures that the British looted in 1897 after a punitive expedition against the West African kingdom, and which ended up in all major European museums.

Germany has not sat on its hands either: since the former Museum für Völkerkunde returned a statue to the ex-British colony of Zimbabwe in 2003, scientists have been investigating the provenance of thousands of pieces that German settlers and collectors brought back from Cameroon, Tanzania, and Togo at the time.

Germany also has a collection of bronze sculptures from Benin. But not for much longer. The controversy that accompanied the opening of the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, where Völkerkunde has found a new home, also gained momentum there. The images from Benin are a litmus test for the way in which Germany is dealing with its colonial past, federal culture minister Monika Grueters said at the end of May. ‘We must assume our historical and moral responsibility.’ The first German restitution of bronze sculptures from Benin is scheduled for 2022.

Art historian Toma Muteba Luntumbue: ‘In some states, the legal and ethical framework for restitution has been under construction for three decades’

In the Netherlands, the focus on emotionally charged colonial heritage has also only increased in recent years. In a noted report, the Council of Culture advised at the end of 2020 that looted art and culture objects should be unconditionally returned to the countries of origin, free from logistical, legal, and other objections, with Indonesia at the head of the queue. Since then, elections have been held in the Netherlands and culture minister Ingrid van Engelshoven has included almost all the Council’s recommendations in her policy vision. From now on, the Netherlands can regard itself as a forerunner in Europe.

‘In some states, the legal and ethical framework has been under construction for three decades’, confirms the Brussels-Congolese art historian Toma Muteba Luntumbue, curator of the Lubumbashi Biennale in 2015 and co-signer of the above letter. ‘I mainly look at Canada, the US, Australia and New Zealand: they have long been at the forefront when it comes to the moral integrity of museum collections. They deal with the subject of restitution in all its complexity and try to rectify historical errors.’

Belgium may not be a pioneer, but the ball has unmistakably started rolling here too. In the summer of 2020, a special committee was set up in the Chamber of the Federal Parliament with the aim of examining the colonial past and formulating recommendations on how best to deal with it. Looted art also receives the necessary attention.

Thomas Dermine, Belgian State Secretary for Science Policy: ‘We have to get away from symbolic politics. It's not ours, period'

In the meantime, the Brussels parliament has set up a working group to decolonize the metropolitan public space, a debate in itself, while Flemish Minister of Education Ben Weyts announced that colonialism would be explicitly included in the new learning outcomes for history for the juniors and seniors in high school. More recently, in June 2021, a group of academics, conservators and heritage specialists – including MAS curator De Palmenaer – presented to the Belgian authorities its Ethical Principles for Dealing with Colonial Collections. The principles are ‘not an endpoint but a contribution to the debate’, according to the researchers. It is important to amend the existing international, European, and Belgian legislation and rules for the protection of cultural heritage, they write. Their core message is clear: implement a transparent restitution policy, work on an equal footing with former colonies and give back generously.

That same June, the news followed that Congo will again become the owner of all objects from the collection of the AfricaMuseum in Tervuren originating from Congo and that were demonstrably obtained illegally between 1885 and 1960. Thomas Dermine, Belgian State Secretary for Science Policy, said in De Standaard: ‘We have to get away from symbolic politics. It’s not ours, period. Whether or not there are opportunities to preserve the heritage in Congo has no impact on ownership.’

Without corona, this news might have come a year earlier. ‘It was planned that the then Prime Minister Wilmès would go to Congo in June 2020,’ says Guido Gryseels, director of the AfricaMuseum. ‘For the sixtieth anniversary of independence, symbolic words would certainly have been spoken there.’ Subsequently, the De Croo government took office, which ‘consists of people who were largely born after 1960 and who do not feel called upon to whitewash any aspect of the colonial past’, says Gryseels.

Curator Nadia Nsayi: ‘There is a new openness. Although the debate is still too Belgian'

‘There is a new openness’, admits Nadia Nsayi, ‘Although the debate is still too Belgian. Except for a few groups, the theme of restitution is not yet a lively topic of discussion within the diaspora. That has to do with ignorance, but above all with the fact that there are so many other, more urgent issues on the agenda.’

‘Trop belgo-centre’, Luntumbue also calls the discussion. ‘Until today, in the political, scientific, and cultural spheres, I hear the tendency to speak for the Other. Not to mention the opacity and opportunism that characterize the Belgian debate. We had to wait for Savoy and Sarr in France before politics really started talking about restitution here too.’

Legal versus ethical owner

Guido Gryseels knows how touchy the subject is. Belgium is not at the tail end of Europe, but why is it so slow? ‘A lot has to do with the fact that 80 percent of our collection is Congolese. In Congo, the context is different from Benin and Senegal, where the voices for restitution are louder. But the AfricaMuseum is really open to it. If Congo and Rwanda officially request it, pieces will go back.’

Guido Gryseels, director of the AfricaMuseum: 'If Congo and Rwanda officially request it, pieces will go back'

However, we are by no means there yet. Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi said it himself at the official opening of the new National Museum in Kinshasa in 2019: as long as the Congolese house is not in order, restitution is not a priority. For Congo, it is important that the documents are stored in the best possible conditions, says Tshisekedi. Even a limited symbolic transfer is not yet on the agenda.

Gryseels: ‘Even now that Kinshasa has a museum, Congo is still struggling with major storage problems for pieces of national heritage. Moreover, Kinshasa does not speak of restitution, but of reconstitution, a targeted search for objects that the country lacks in its own collections. For example, we have a lot of Yaka masks here, there is a great demand for them in Congo.’

Power statue (nkishi) by chief Nkolomonyi, Songye people

Power statue (nkishi) by chief Nkolomonyi, Songye people© MAS, Antwerp / Photo: Michel Wutys and Bart Huysmans

Only: which object goes where? Who is the legal owner, and who is the ethical one? All the pieces in Tervuren, some 120,000 ethnographic objects and 8,000 musical instruments have been inventoried, but that does not mean that the method of acquisition is also known. Much material, for example, was brought by missionaries, who in some cases were anthropologists avant la lettre. But did they receive the pieces as a present? Did they pay the market price for them, or did they acquire them within a certain power relationship? What has been plundered and what has been looted?

‘The provenance investigation is underway,’ says Gryseels. ‘We are looking at where the gaps are. We explore the museum itself and two of our scientists have carried out fieldwork in Congo. There is no doubt that a number of pieces belong there.’

For example, Ne Kuko, the statue of the village chief of Kikuku. ‘It was looted, and we know it. But who is entitled to request it be restituted? Should Ne Kuko return to his village so that he can resume his symbolic and identity role as a protector of the community? Or should the statue go to Kinshasa, more than a thousand kilometres away? The village chief may not need restitution if Ne Kuko ends up in the capital. We do not yet have a solution for these kinds of questions.’

Logistics not an argument

There is yet another problem, says Toma Muteba Luntumbue: ‘That the most powerful, most symbolically charged objects are often considered diabolical by the evangelical churches. Many religious, of whatever denomination, reject exhibitions with certain cultural objects. Moreover, many Congolese want to get rid of the concepts of “tribe” and “ethnic” to which the objects are linked, and which are of colonial origin.’

‘In order not to fall into the trap of that complex and very ideological debate, Tshisekedi remains pragmatic. And honestly: if all pieces of Congolese heritage abroad return to Congo, there will simply be no room for them in the National Museum. But that should not be an excuse for opponents of restitution, who pretend the lack of competence in Africa is the reason not to have to give anything back. In that respect, a strong political demand for restitution is necessary.’

Congo must have maximum access to its own heritage without logistical aspects becoming a condition, says Gryseels. ‘But we don’t have the necessary legal framework yet. One of the options is for Congo to acquire ownership of the pieces and for us to rent them while waiting for some of them to go there. We are also strongly committed to collaboration, in museological and scientific terms.’

Colonial propaganda photo with Congolese having to pose in front of a slit drum. Antwerp World Exhibition, 1894

Colonial propaganda photo with Congolese having to pose in front of a slit drum. Antwerp World Exhibition, 1894© RMCA, Tervuren

Human remains

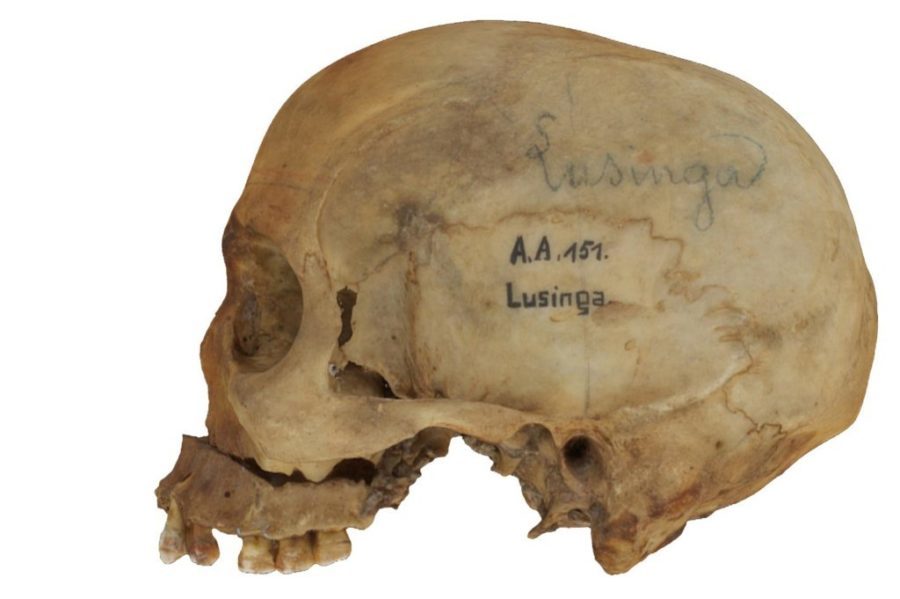

Incidentally, the restitution issue is about more than artefacts. Human remains are also present in Belgian collections: in particular, dozens of skulls, some of Congolese who were executed during colonial punitive expeditions. The skulls were brought along as trophies, some of them – especially those of the Tabwa village chief Lusinga – were on display in Brussels salons for decades.

Lieutenant Emile Storms’ men were the ones who killed and beheaded Lusinga in 1884. Storms, commander of the Association Internationale Africaine (AIA), dispatched by Leopold II, also wanted to teach other intransigent chiefs a lesson. He burned down several villages of Lusinga in a single day, an action that left sixty dead and one hundred and twenty-five villagers were taken prisoner.

Skull of the Tabwa village chief Lusinga

Skull of the Tabwa village chief Lusinga© irsnb

After Storms’ death, his relatives transferred Lusinga’s skull to the museum in Tervuren, after which it eventually ended up in the Museum of Natural Sciences. It is on display there, with a label, in the depot.

‘Two branches of Lusinga’s family want the skull back,’ says Patrick Semal, curator of the anthropological collections at the museum. ‘It is likely that his remains will be returned to the family, although it is not yet clear to which branch.’ Just as it is not clear what the legal status is of Lusinga’s and other skulls that have since been identified.

‘To answer these questions, we founded HOME (Human Remains Origin(s) Multidisciplinary Evaluation, LD)’, says Semal, ‘a collaboration between the various Belgian institutions that have human remains in their collection. Some of these date from colonial times, such as the skulls from Congo. With HOME we want to gain insight into the historical, scientific, and ethical context in which the material was acquired, and to propose a legal framework for restitution.’

‘Unlike Great Britain, France or Germany, Belgium has not yet carried out such a study and has not created a clear framework for it’, says legal specialist Marie-Sophie de Clippele of the Université Saint-Louis in Brussels, co-author of the above-mentioned Ethical Principles and one of HOME’s partners. ‘The classic question is: what are human remains after death? Is a skull an object and therefore negotiable? Does it remain a human being? Or is it in a grey zone in between? In the French Civil Code, they solved that by adding that respect for the human body does not end with death. In Belgium, the Advisory Committee on Bioethics has a role in this.’

However, the lack of legal means does not have to preclude restitution. If a case is not time-barred and there is evidence, next of kin can go to a criminal or civil court. Solutions can also be devised through diplomacy.

‘In any case, restitution must be in line with the work that the parliamentary committee is doing today and be discussed in parliament,’ says De Clippele. ‘The debate should not be confined to academia.’

Statue of a white man (mundele) with a walking stick and straw hat

Statue of a white man (mundele) with a walking stick and straw hat© MAS, Antwerp / Photo: Michel Wutys and Bart Huysmans

‘Restitution, including that of Lusinga’s skull, should be part of a historic exercise,’ adds Semal. ‘Our country simply has to be ready the moment such restitution is formally requested. Human remains or cultural property can only be returned once. We must not be mistaken, that one time has to be the right time.’

‘If Congo makes it a priority, the restitution will become a fact’, Guido Gryseels repeats, although he also wants to point out that ‘by no means everything that is in Belgian possession is illegal’.

And the fear of some that our museums will soon become empty shells? ‘Unfounded’, emphasizes Gryseels. ‘No one claims the entire collection. Even if we return hundreds of items, it won’t make a significant difference.’