Religious History and Current Affairs Come Together in the Luther Museum

Martin Luther, the founder of Protestantism, was widely followed in Amsterdam. In the seventeenth century, as much as a fifth of the city’s population was Lutheran. The origin story of Luther’s Netherlands comes to life in a beautiful museum, housed in a monumental building from 1772 that once provided shelter for the Lutheran poor, elderly and orphans in the city.

Sunday lunch: white bread soup, beer and bread in the evening. Monday afternoon: grey peas, buttermilk in the evening. And so forth, until the menu of all weekdays is complete. It is written on the wall of the room where the food in question was served in 1772. If your eyes scan the entire list, you can almost hear the silent chewing and slurping of the old men and women who enjoyed their meals in this room twice a day and attended mass here on Sundays. Today, the church hall is the heart of the Luther Museum, where the eighteenth-century organ is a reminder of earlier times.

The church hall with its eighteenth-century organ is the heart of the Luther museum.

The church hall with its eighteenth-century organ is the heart of the Luther museum.© Goulmy

The Luther Museum is one of the undiscovered gems of museal Amsterdam. It is located in a quiet part of the city, sandwiched between the Hortus botanical garden, Artis Zoo and buildings of the University of Amsterdam. Even during the tumultuous pro-Palestinian student demonstrations, it remained a place of peace and tranquillity.

The Luther Museum opened in summer 2019 and had to go into lockdown like the rest of the Netherlands less than a year later, which partly explains its relative obscurity. It wasn’t until 2023 that the institution was open for a normal year. At that time, 6500 visitors managed to find the monumental building on the Nieuwe Keizersgracht. Such figures pale in comparison to the Resistance Museum or National Holocaust Museum that also opened only recently, but the name Luther probably rings fewer bells with the average visitor than the Second World War in these secularized times.

Monumental building on the Nieuwe Keizersgracht, circa 1773

Monumental building on the Nieuwe Keizersgracht, circa 1773© Collectie Atlas Dreesmann, Stadsarchief Amsterdam

Nowadays the Lutheran community in the Netherlands only consists of between eight and ten thousand members. The number of followers of the preacher who nailed his 95 anti-Roman Catholic theses to the church doors of Wittenberg in 1517 and thus laid the foundation for Protestantism, was once much greater. Amsterdam especially was a popular refuge for Lutherans from Germany and Scandinavia. In the seventeenth century, as much as a fifth of the city’s population was Lutheran.

From poorhouse to museum

In addition to including members of the board of the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company, the church also included quite a few poor people. The Evangelical-Lutheran Diaconate Old Men’s and Women’s Home was built for them. Because the municipality made a vacant piece of urban expansion available, it was possible to realize sizeable premises. As a sign of gratitude, master builder Coenraad Hoeneker equipped the church hall with an ornamental ‘mayor’s gate’, in which the coats of arms of four mayoral families from that time can be recognized, in combination with the swan, the omnipresent symbol of the Lutheran community.

The 'mayor's gate' in the church hall

The 'mayor's gate' in the church hall© Luther Museum

In 1769 the first five hundred people in need of help moved in. Men and women lived separately and worked as carpenters and seamstresses, respectively. Later, it also accommodated orphans. Until 1967, the home was only intended for members of the Lutheran church, but subsequently was eligible for everyone. More than half a century later, the last elderly people left, and a start was made on transforming it into a museum. The back half of the building has been converted into a long-stay hotel, the proceeds of which flow to the diaconate and a small part to the museum.

International guests from cultural institutions in the area often stay here, such as Ellen Reid who was recently invited by the museum to compose in the church hall. In doing so, she was able to make use of the organ and the historic grand piano from the Geelvinck Collection. These instruments are also used during the Bach Week and performances by conservatory students. Tickets are sold for these events, but for the recent ‘introductory lunch for residents, students and new Amsterdammers’, for example, the doors are opened free of charge.

Dark history

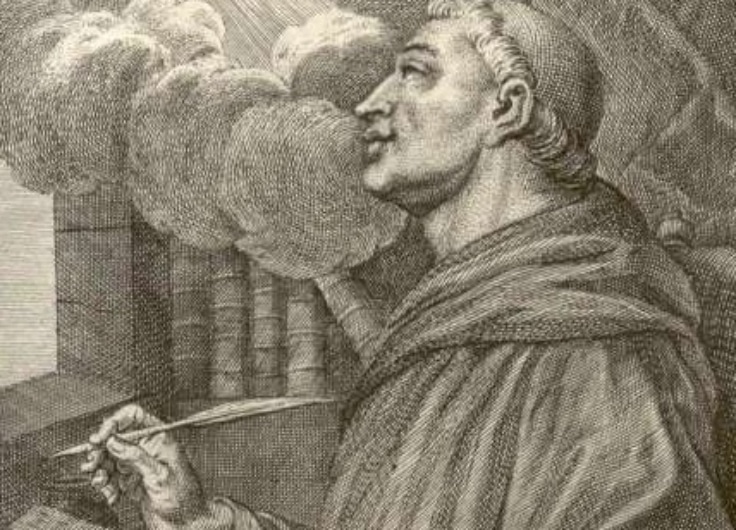

Helpfulness, care and solidarity are Lutheran values that permeate both the building and programming. While there is only one image of Christ in the entire building – looking out from the clouds in a painting that is a copy of Rubens’s Conversion of Saul – the great inspiration is omnipresent. In the church hall, the place of honour has been set up for a painting showing the trial in Worms, where Luther refused to swallow his criticism of the pope and was labelled a heretic by Emperor Charles V.

The gentlemen’s regent’s room to the right of the entrance also focuses completely on Luther. The death mask and casts of his hands are a bit creepy, but one large painting shows the theologian as a friendly family man playing the lute for his offspring. The masterpiece in this room is the Ruysdael painting with the conversion of the eunuch as its subject. With this story from Acts of the Apostles about the chamberlain of the Ethiopian queen, the artist emphasized that Christianity is not an exclusively European but a universal religion.

The gentlemen's regent's room with a couple of Ruysdael paintings.

The gentlemen's regent's room with a couple of Ruysdael paintings.© Goudry

The fact that millions of Africans have been oppressed, trafficked and murdered in the name of that same Christianity – crimes of which Lutherans have also been guilty – is not swept under the carpet here. These dark pages of history were fully covered in the exhibition entitled Churches and Slavery, one of the first ones organised by the museum. For the occasion, Nelson Carillho made a chilling sculpture that is now placed right beneath the Ruysdael painting. An African figure is driven into the ground with large nails, the body is mutilated, and a cross has been rammed into the head from above.

Secret stairwell

Such a self-assured contemporary accent is made even more intense by the contrast with the richly decorated interior of the room. This is where the regents arranged their administrative and financial matters – reason enough to close off the room with a double door so that no eavesdropping could take place. In the privacy of their meeting room, they regularly drank heavily. When the drinking went too far, they took a secret staircase to the garden, so that residents of the poorhouse did not see them. The wretches were subject to a strict ban on alcohol, which was enforced with severe penalties.

The lady regent's room is as big as its male counterpart.

The lady regent's room is as big as its male counterpart.© Goudry

The hypocritical shortcut is in the room where the linen used to be kept and today the silver collection. The last of the three connected rooms was reserved for the lady regents. The fact that this space is the same size as their male counterpart says something about egalitarianism in the Lutheran church. At one point, the poorhouse even had a mixed board, as evidenced by a large group portrait. On the far left is Georgine Schwartze, the famous portraitist and sister of the equally well-known Thérèse. Her father, who is also a painter, has always remained in the shadow of his daughters, but this autumn the Luther Museum will put him in the spotlight.

Socially relevant exhibitions

These kinds of art-historical exhibitions are interspersed with presentations on socially relevant themes. The exhibition Welcome to the Netherlands? was quite impressive, which told the story of 789 Lutherans who were expelled from Salzburg in 1732. At the invitation of the States General, they travelled to the Netherlands, where they were dropped in a remote corner of Zeeland and left to fend for themselves. It is not hard to draw parallels with the current reception of asylum seekers, who are condemned to sleeping in the open air and dead-end bureaucratic procedures due to administrative reluctance.

The exhibition Welcome to the Netherlands? told the story of expelled Lutherans.

The exhibition Welcome to the Netherlands? told the story of expelled Lutherans.© Luther Museum

The heart of Welcome to the Nederlands? consisted of historical objects but the presentation was taken to the next level by the contemporary addition of kathas. These multi-coloured scarves with wishes of welcome were made by the Rainbow Soulclub, a collective of homeless people, (former) addicts and undocumented migrants. After the exhibition, the museum added some of the kathas to its collection. It is not only made up of historical pieces but is regularly expanded with commissioned works by contemporary artists.

Kathas on display: multi-coloured scarves with wishes of welcome

Kathas on display: multi-coloured scarves with wishes of welcome© Luther Museum

For example, Koen Taselaar made a communion rug to mark the occasion of Ascension Day 2024. Incidentally, it is not kept under a bell jar or in a cupboard but will soon travel to Lutheran churches in the country where it is used in church services. And that also applies, for example, to the chalices and the silver table bell. The Lutheran community may have almost disappeared, but this museum breathes new life into Lutheran history.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.