Mad Meg or the Weirdness of the Masterful Detail

The Flemish playwright and theatre director Lisaboa Houbrechts has been inspired by Mad Meg (Dulle Griet), the famous painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525-1569). She created a performancce in which ‘manwife’ Mad Meg wrestles with her own body and identity and is looking for answers. The theatrical piece has the potential to heal, even for Houbrechts herself.

Some artists occupy the special role of ‘masters’ in our collective memory. But what is a master? In the sixteenth century, one became a master in a guild by making a test piece, a masterpiece. Admission to a guild gave artists the right to independently practice their art. A master proved his ability to synthesise all the wisdom he has. He had knowledge of different domains of philosophy, of science, of the human and the spiritual and could gather all of these together in one authentic artistic expression that transcended the moment of creation.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Mad Meg, 1563, Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Mad Meg, 1563, Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp© KIK-IRPA, Brussels

In a great work we often find a curious detail created by the master. The best-known examples are probably Wagner’s bizarre Tristan chord or the mysterious smile on Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. In such cases, the artist follows his intuition. But what is the nature of this intuition? How can a specific detail in a Da Vinci painting still fascinate viewers today? Masters are often called ‘visionary’. They have a sort of intuition about a detail that is off-trend and misunderstood at the time, but which suddenly becomes important later. A masterpiece, then, is not always the realisation of something great, but can consist of details born of intuition that continue to fascinate and bedevil our culture. Which details from the past can potentially become tomorrow’s revelations?

Is Mad Meg an actress?

One of those mysterious details in Bruegel’s body of work is the curious character Mad Meg, about whom I developed a theatrical performance. Mad Meg depicts a masculine woman – an object of derision – armoured and armed, who rampages through hell while a bestial sexual act is carried out in the background. Her gender is ambiguous; she has an Adam’s apple and huge feet and carries a raised sword in her hand. These are weird details. The painting is an allegory and, with it, Bruegel enters the domain of literature. In a phantasmagorical universe he designs a symbolic image-rhyme populated by beings straddling the boundaries between animals, objects and humans.

Anne-Laure Vandeputte plays Mad Meg in the performance 'Bruegel', Het Toneelhuis, Antwerp, 2019

Anne-Laure Vandeputte plays Mad Meg in the performance 'Bruegel', Het Toneelhuis, Antwerp, 2019© Kurt Van der Elst

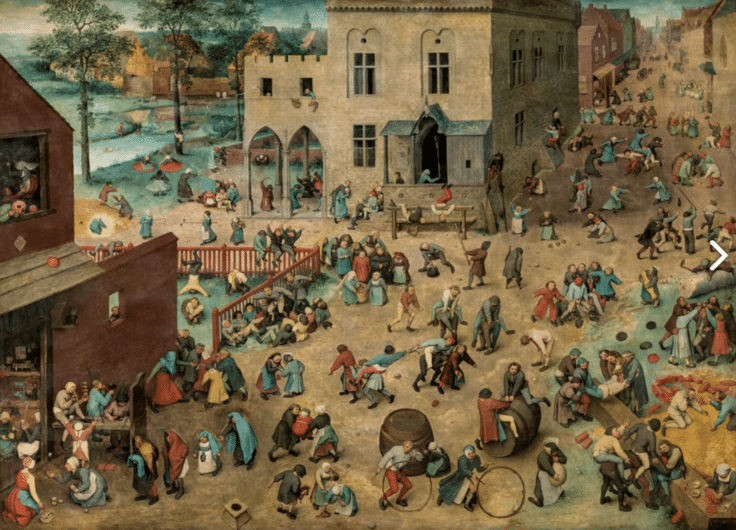

There is not a single extant note in Bruegel’s hand explaining or clarifying why he painted this boundary-breaking painting. We know that his work was done on commission for customers who chose the themes themselves; from religious subjects such as virtues and sins, through famous proverbs to children’s games. A favoured place to display a painting was on a wall near the dining table. In this way, the paintings served to stimulate conversation between the wealthy buyers and their dinner guests. The humanists of the sixteenth century habitually gathered around such dining tables in convivia to interpret and discuss all the iconographic details in the painting from the perspective of various themes. Erasmus himself described how thoughts were activated by the quantity and unfamiliarity of those details. These artworks, called conversation pieces provided them with food for thought. The unfathomable painting of Mad Meg was such a conversation piece – and it still entangles our thoughts today. If only this painting could still hang on the dining room walls of theatrical producers today! The scenographic details of the landscape show that Bruegel was inspired by the rhetoric plays and Dutch farces of his time. In the sixteenth century, women were not permitted on the stage, so men played all the female roles. Is this the explanation for the mysterious, masculine details of Mad Meg’s body? Is she an actor? And what might that mean in relation to the allegory surrounding the sexual assault happening in the background of the painting? We have no idea.

An unexplainable phenomenon

This strange detail punches a hole in our understanding. It is the kind of blank space that fascinates us and makes history so enticing. Mad Meg is an image we cannot get our heads around.

With abstract painter and scenographer Oscar van de Put I tried to fill that hole in our understanding by creating a performance piece about the mysterious details in the painting. In the performance, I bring the master, Bruegel, back to life just as he is working on the painting. Mad Meg speaks and confronts the master-painter with her internalised experience of the comically meant, masculine details he used to depict her body. She tries to explain what it means to be trapped inside this strange body he created for her. My goal was to add something to the work of the master deriving from my personal necessity to shape the gender-fluid image

Image from the performance 'Bruegel'

Image from the performance 'Bruegel'© Kurt Van der Elst

In the performance, Mad Meg wants to examine the archaeology of her body. I let her travel back in time during her quest so she can confront historical women as well as iconic images of women. She comes face-to-face with the Greek goddess, Athena, and with Mayken Verhulst, the forgotten miniature painter and mentor of Bruegel, whose body of work has disappeared. From each of those encounters Mad Meg brings an object back into the present. Oscar van der Put gave form to these objects, blowing them up to gigantic pop-art proportions to create a scenography of abstract, archaeological artefacts. Mad Meg drags these objects across the stage, just as she seems to have stolen or collected objects in the painting. She wants to collect all these objects, these lost details from the dark side of history, as shards that she believes are the fragments of her own mirror. Yet she concludes that the women’s artefacts she digs up have nothing to do with her. She is forced to accept that she is an inexplicable phenomenon, neither male nor female, an allegory, a sexless angel. She is the smile on Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa: the weirdness of the masterful detail.

Image from the performance 'Bruegel'

Image from the performance 'Bruegel'© Kurt Van der Elst

It is often argued that the works of the Old Masters still appeal to viewers today for their universal strength and timelessness. Personally, I believe that we still respond to ancient art because of the presence of the strange, the outdated and the inexplicable details. Bruegel masterfully depicts man as the seeker. He confronts us with a quest to find the undiscoverable truth. That strange hole in our understanding provided me with an opening through which I could dissect Mad Meg and pour my own story into her old body. Sometimes you need to somehow inhabit bodies from other times to bend, historicise and abstract your own story, and thereby provide a mysterious healing effect to both the maker and the audience.