Madness, Mourning, and Sadness Surround Flemish Primitive Hugo Van Der Goes

The Death of the Virgin, a masterpiece by Hugo van der Goes from the fifteenth century, has been restored. The result can be admired in a versatile exhibition in Bruges, built around the panel. A combination of old and new masters invites you to look closely, but also to let yourself be touched.

Whoever enters the exhibition Face to Face with Death in the Sint-Janshospitaal (St. Johns Hospital) in Bruges, comes face to face with madness. A man in what could be an open-hanging monk’s habit sits huddled on a wooden throne, his hands cramped, his haggard gaze looking right through you. It’s Hugo van der Goes.

Or at least: it is Van der Goes as painter Emile Wauters saw him in the nineteenth century. He portrayed the late medieval painter as a mentally ill person whose suffering was alleviated by music therapy. In addition to Van der Goes, four choirboys are singing, accompanied by a few musicians.

Emile Wauters portrayed the late medieval painter as a mentally ill person whose suffering was alleviated by music therapy.

Emile Wauters portrayed the late medieval painter as a mentally ill person whose suffering was alleviated by music therapy.© Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

The nineteenth-century myth of the tormented genius is given little credence today. Contemporaries were full of admiration for the virtuosity of Hugo van der Goes (ca. 1440-1482). And today, art historians consider him a master on par with Jan and Hubert van Eyck or Rogier van der Weyden. The strange work of Wauters, in which the colour brown predominates, is therefore in great contrast to the panel by Hugo van der Goes that is literally central to the exhibition: The Death of the Virgin.

A marble-white Mary on her deathbed is surrounded by grieving apostles. Above her head, her son appears in a vision. The blue is overwhelming: the blue of Mary’s robe, the blue fabric with which the bed is covered, the many blues in the vision, the robes of some apostles, and a blue curtain, in different shades each time.

The Death of the Virgin by Hugo van der Goes. The hands speak, as do the looks. The sadness is written on the faces.

The Death of the Virgin by Hugo van der Goes. The hands speak, as do the looks. The sadness is written on the faces.© Musea Brugge, artinflanders.be, photo by Dominique Provost

You can hear a pin drop. One of the apostles protectively holds his hand around a candle flame, trying to prevent it from blowing out. The hands speak, as do the looks. The sadness is written on the faces. The Death of the Virgin is a poignant work that can still touch us after almost 550 years.

Universal

It is difficult to describe why the work is so intriguing and moving. The fresh and surprising colours attract attention, as do the individualized faces. The composition also contributes to the power of the panel: it seems as if you yourself are present in Mary’s last moments. The theme of mourning and grief is universal and therefore recognizable. Despite the modesty and unmistakable sadness in the work, there is also hope.

In response to the years of restoration of the Flemish masterpiece, the exhibition Face to Face with Death

highlights the painting from five lines of approach. These are starting points to better experience and understand The Death of the Virgin. They set up a dialogue between, on the one hand, old art and historical objects that place the panel in a broader context and, on the other, emotions that still appeal today.

Hugo van der Goes was known by his contemporaries as an innovator

Such themes as “parting”, “meaning” or “Mary icon” are obvious. The items “virtuoso” or “experiencing” are at first glance more surprising. Each of the themes that touch upon on that which the exhibition radiates is complemented by a reflection or testimony by a contemporary artist. These are names that appeal to the imagination: the authors Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer and Sholeh Rezazazadeh, theatre director Ivo van Hove, visual artist Berlinde De Bruyckere and choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. In sober black-and-white videos, they tell what strikes them in the panel and make connections with their own life or work.

Memento mori

The themes are evoked through some seventy very diverse works: there are sculptures, paintings, manuscripts, archival documents, liturgical tableware, part of a choir cap, but also prayer beads and a Christmas cradle. In some places, you can also listen to music.

For example, the theme of “parting” highlights the ubiquity of death in the fifteenth century and the ways in which people could prepare for it. A life-size statue of Saint Christopher – which would offer protection against sudden death – is joined by a painting with the Last Judgment and by a letter of indulgence.

The panel by Hugo van der Goes is literally central to the exhibition.

The panel by Hugo van der Goes is literally central to the exhibition.© Musea Brugge

A diptych by Jan Provoost with a cross-bearing Christ and a Friar Minor also attracts plenty of attention. The exterior panels form a memento mori, with a rebus and a skull. A prayer bead with the same theme dangles nearby. A manuscript contains the funeral liturgy of a bishop. There is a moving painting of an ordinary woman on her deathbed and the Gruuthuse manuscript is temporarily present in Bruges again. In it you can read the Egidiuslied, the famous rondeau about the lament of the death of a friend named Egidius.

Among these works, the Iranian-Dutch writer Sholeh Rezazadeh talks about saying goodbye to her native country when she moved to the Netherlands in 2015. She also points us to the hope that speaks from The Death of the Virgin to the candle flame and the light in the painting. In this way, as a “new master”, she connects Van der Goes’ work with the contemporary visitor. It is a pity that the videos with contemporary artists are centred around their person – however interesting – and that we do not see or hear any of their work.

Masterpieces

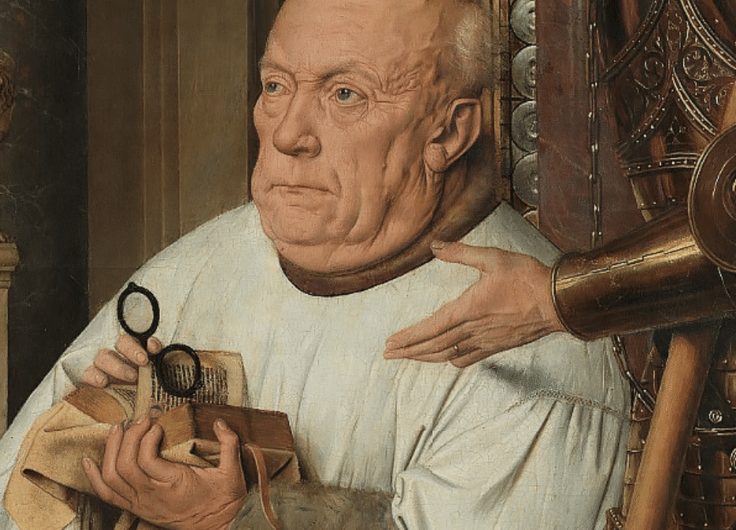

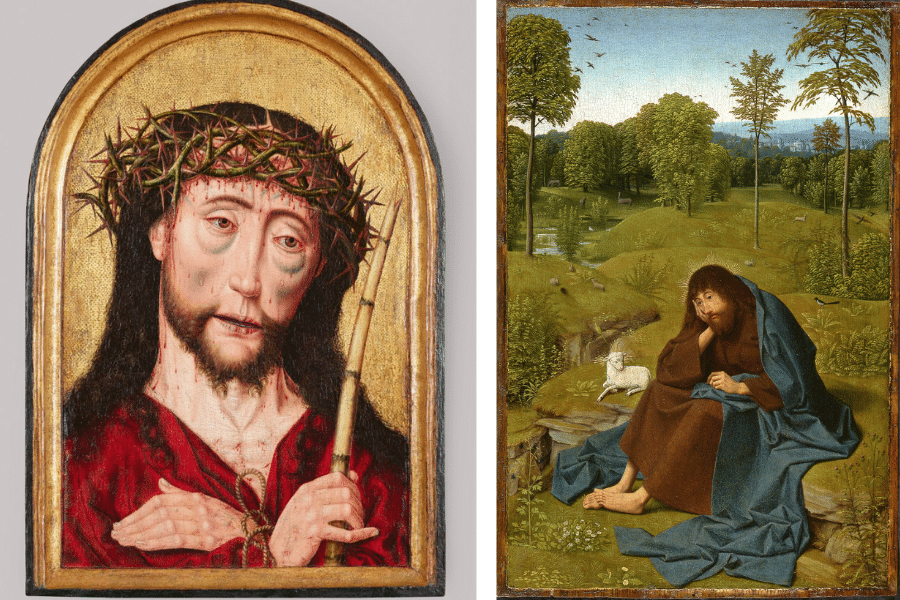

Van der Goes’ panel is the starting point and the centre of the exhibition, but there are still some other masterpieces on display. There is a Man of Sorrows by Albrecht Bouts, the polyptych with The Life and Death of the Blessed Virgin by Barend van Orley, as well as the special panel John the Baptist in the Wilderness by Geertgen tot Sint Jans.

Hans Memling is represented by the diptych of Maarten van Nieuwenhove and by the reliquary of Saint Ursula. The Sint-Janshospitaal also houses other beautiful works by Memling that you can go and see after the visit to Face to Face with Death.

The exhibition encourages you to look intently, to notice details that you had not seen before, and to compare

Not every line of the approach taken by the exhibition is equally compelling. “Experiencing” is the least elaborate and is evoked in only a few objects. The theme ties in with the theatricality suggested by the curtains in Mary’s room. At the same time, it refers to late medieval mystery plays, such as the Joys of Mary, which also features Mary’s last days.

Because of the arrangement of the works, you automatically return to The Death of the Virgin a few times. The exhibition encourages you to look intently (again), to be amazed at the realistic faces of the apostles, to notice details that you had not seen before, and to compare. After all, we know little about Hugo van der Goes and many of his works have been lost, but he was known by his contemporaries as an innovator. His work was copied and imitated. Some of these works are included in the exhibition.

Sparkling

The colours of the restored panels will continue to astonish you, with their sparkling freshness. The restoration itself is depicted in a meditative short film. With endless patience, the restorer removed the varnish and later overpainted and fixed the original paint layer. Where necessary, she has retouched.

'Man of Sorrows' by Albrecht Bouts and 'John the Baptist in the Wilderness' by Geertgen tot Sint Jans

'Man of Sorrows' by Albrecht Bouts and 'John the Baptist in the Wilderness' by Geertgen tot Sint Jans© Musea Brugge, photo by Matthias Desmet / Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Face to Face with Death is rich and layered, but the exhibition also sometimes feels a tad overcrowded and fragmentary. There is no required route to take, so you can map out your own way between the very different works, objects, and videos. You can watch, read, and listen, the exhibition tries to touch and appeal to you in all kinds of ways. The latter sometimes literally leads to polyphony: in some places, different videos with the reflections of the “new masters” all resound simultaneously.

The end of the exhibition ties in with the music therapy for Hugo van der Goes. Under the heading Music is my medicine you can listen to testimonies about the healing power of music, and the comfort and inspiration it offers people. Visitors can add their own pieces of music. A last way to let yourself be touched and inspire others.

Face to face with Death. Hugo van der Goes, Old Masters and New Interpretations, Sint-Janshospitaal, Bruges. Until 5 February 2023.

To coincide with the exhibition, a beautiful book was published about the life and work of Hugo van der Goes.